The Poets and the Poetry of the Century

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Researching a Single Journalist 1

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Greenwich Academic Literature Archive 1 Researching a single journalist Alfred Austin John Morton In the introduction to the Routledge Handbook to Nineteenth-Century British Periodicals and Newspapers, Alexis Easley, Andrew King, and I identi- fied several periodical types our volume had not dwelt on in detail. Among these were party political journals. While several journals with loose political affiliations were discussed in passing (for example, Blackwood’s Edinburgh Review, which was founded as something of a Tory corrective to the Whig Edinburgh Review), they were not treated primarily as organs of political ideology. Before co-writing the introduction to the Routledge Handbook, I had already decided to undertake a study of Alfred Austin for this chapter; it is a genuine coincidence, although not an unhappy one, that at every stage of his career Austin betrayed a definitively Conservative outlook and founded one of the most influential late Victorian Conservative journals, the National Review. This chapter, in addition to considering Austin as a political journalist and establishing this as the primary factor behind his appointment to the laureateship, will also through practice demonstrate the difficulty – in fact near-impossibility – of researching one nineteenth-century journalist in isolation. Austin is nowadays remembered for what many would term the wrong reasons, chief among these his status as the apparently least deserving poet laureate in British history. I first came across his work when writing my PhD thesis, which investigated the critical and cultural legacy of Alfred Tennyson in the sixty or so years after his death. -

Laureateship Under the Reign of Queen Victoria

English Language and Literature Studies; Vol. 3, No. 4; 2013 ISSN 1925-4768 E-ISSN 1925-4776 Published by Canadian Center of Science and Education Laureateship under the Reign of Queen Victoria Mohammed Kasim Harmoush1 1 Faculty of Arts, King Abdul Aziz University, Jeddah, Saudi Arabia Correspondence: Mohammed Kasim Harmoush, Associate Professor of English, Faculty of Arts, King Abdul Aziz University, Jeddah, Saudi Arabia. E-mail: [email protected] Received: October 15, 2013 Accepted: November 1, 2013 Online Published: November 28, 2013 doi:10.5539/ells.v3n4p68 URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.5539/ells.v3n4p68 Abstract Many foreign learners of English in our Middle Eastern universities encounter terms such as poet laureate or laureateship without troubling themselves to search for the origin of these terms, or even taking enough time to specify their true meanings or identify the poets honoured with the title of poet laureate, and how the candidates are selected in Victorian times. This paper is designed to give answers to the above speculations. Upon reviewing many sources in this regard, we become sure that the title of Laureateship is often offered by the authority to a man of letters not necessary very well-known poet, but to a man who could serve the Queen by writing poems or articles celebrating her royal occasions and sharing her the same political taste. Keywords: laureateship, Victorian poets, Queen Victoria, Victorian times 1. The Main Discussion We believe that shedding light upon this topic is a useful and interesting undertaking in the present. This paper mainly focuses on the poets laureate of the Victorian period. -

Poison, Medicine, Or Nutrition an Ebook Is

ALCTS "When are eBooks THE Books?" 2004 ALA Annual Conference Orlando Forum E-Books: Poison, Medicine, or Nutrition When Are E-Books the Books? Kimberly Parker ALA 2004 Annual Meeting 28 June 2004 Its varied scenes, its many hopes and fears … Thomas Cole. Thomas Cole's poetry. “Voyage of Life” 1972 An Ebook Is … • Individual • Package • Historical/Textual • Reference Work • Textbook ALA 2004 Orlando www.ala.org/alcts 1 ALCTS "When are eBooks THE Books?" 2004 ALA Annual Conference Orlando Forum Heav'n grant we be not poison to each other … John Dryden, Sir William Davenant , Thomas Shadwell. The Tempest. Act II Scene 2. 1674 The Metaphor • Poison • Medicine • Nutrition ALA 2004 Orlando The swelling tide of time ... Robert Anton. The Philosophers Satyrs. The Philosophers Third: Satyr of Iupiter. 1616 Timeline • 1991 Patrologia Latina • 1994 PastMasters • 1996 Oxford English Dictionary (1) • 1997 English Prose Drama • 1999 Early English Books Online (>100,000), Eighteenth Century Fiction, ENGnetBASE, STAT!Ref(9) ALA 2004 Orlando www.ala.org/alcts 2 ALCTS "When are eBooks THE Books?" 2004 ALA Annual Conference Orlando Forum And cause and sequence, and the course of time ... Sir Edwin Arnold. The Light of Asia or The Great Renunciation (Mahâbhinishkramana). Book the Eighth. 1879 Timeline (cont.) • 2000 Early English Prose Fiction, etc. • 2001 Books@Ovid(growing to 167), Classic Protestant Texts • 2002ACLS History E-book Project (500), Gutenberg-e, Knovel(174), Wright American Fiction ALA 2004 Orlando What's to be done? Nor time nor tide will wait. Alfred Austin. The Golden Age. 1871 Timeline (cont.) • 2003 Acta Sanctorum, Books 24x7 (2,526), CogNet, Digital Dissertations, Evans Digital Edition (>36,000), netLibrary(3500), SourceOECD, World Bank e-Library(1260) • 2004 BioMedProtocols (373), CinemaGoing, Dekker Ebooks(55), Eighteenth Century Collections Online (>130,000), Safari Tech Books (125) ALA 2004 Orlando www.ala.org/alcts 3 ALCTS "When are eBooks THE Books?" 2004 ALA Annual Conference Orlando Forum It was the crave for intellectual food .. -

Tennyson's "Enoch Arden": a Victorian Best-Seller Patrick G

University of South Carolina Scholar Commons Faculty Publications English Language and Literatures, Department of 1970 Tennyson's "Enoch Arden": A Victorian Best-Seller Patrick G. Scott University of South Carolina - Columbia, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/engl_facpub Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Publication Info 1970. Scott, Patrick. Tennyson's "Enoch Arden": A Victorian Best-Seller. Lincoln: Tennyson Society Monographs, no. 2, 1970. http://community.lincolnshire.gov.uk/thetennysonsociety/index.asp?catId=15855 © P. G. Scott 1970 This Book is brought to you by the English Language and Literatures, Department of at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Tennyson's Enoch Arden: A Victorian Best,Seller i i I ',!I P. G. SCOTT ! I I The Tennyson Society Tennyson Research Centre Lincoln i 1970 I i!I I Tennyson Society Monographs: Number Two © P. C . SCOTT 1970 , , Prin ted by Keyworth & Fry Ltd" Lincoln, England, I. ,• I' Tennyson's Enoch Arden: A Victorian Best-Seller In 1864, Tennyson was famous; the 1842 Poems and In l'vIemoriam ( 1850) had established his reputation with the thinking public, and Idylls of the King ( 1859) with the greater number who looked for a picturesque mediaevalism in their verse. His sovereign had named him Poet Laureate, and his countrymen accorded him the hero worship typical of the Victorian era. It was at this point that he published a new poem, Enoch Arden, which went immediately to the hearts of his readers and became a best-seller, yet which has come to be so badly regarded by modern critics that it seldom receives serious attention. -

Issue 9 June 2021

Issue 9 June 2021 View from the Chair Hi Everyone I hope you are all beginning to enjoy the extra freedom we are starting to have now that the Covid restrictions are easing, and we look forward to hopefully more of the group activities commencing soon. In this chairman’s bit I’m including information to bring you up to date on some important matters. I met (via Zoom) with a good number of group leaders earlier in May and, with the ex- ception of the few groups that are already able to meet outdoors, all are planning to re- start in September, government guidelines permitting, which is good news. As I’m sure you can image quite a bit of work will be needed, contacting venues re bookings and going through requirements for the use of the buildings etc which Penny our venues co -ordinator along with the group leaders will be doing. Your group leaders will be in touch with you in the coming weeks. I understand that the Parish Council are considering having a village fete this year on July the 10th, if they do then we will have a pitch as usual. Help manning the stand on the day will be needed and more information will be sent out when known. Many of you will have heard about the ‘u3a Beacon’ database that we use for keeping membership details etc. We are now making available a feature known as ‘The Mem- bers Portal’ where members can check what records we hold about them and update those details should they need to. -

The Bridling of Pegasus by Alfred Austin

The Bridling of Pegasus By Alfred Austin The Bridling of Pegasus by Alfred Austin THE ESSENTIALS OF GREAT POETRY The decay of authority is one of the most marked features of our time. Religion, politics, art, manners, speech, even morality, considered in its widest sense, have all felt the waning of traditional authority, and the substitution for it of individual opinion and taste, and of the wavering and contradictory utterances of publications ostensibly occupied with criticism and supposed to be pronouncing serious judgments. By authority I do not mean the delivery of dogmatic decisions, analogous to those issued by a legal tribunal from which there is no appeal, that have to be accepted and obeyed, but the existence of a body of opinion of long standing, arrived at after due investigation and experience during many generations, and reposing on fixed principles or fundamentals of thought. This it is that is being dethroned in our day, and is being supplanted by a babel of clashing, irreconcilable utterances, often proceeding from the same quarters, even the same mouths. In no department of thought has this been more conspicuous than in that of literature, especially the higher class of literature; and it is most patent in the prevailing estimate of that branch of literature to which lip-homage is still paid as the highest of all, viz. poetry. Chaucer, Spenser, Shakespeare, Milton, have not been openly dethroned; but it would require some boldness to deny that even their due recognition has been indirectly questioned by a considerable amount of neglect, as compared with the interest shown alike by readers and reviewers in poets and poetry of lesser stature. -

From Gallows to Palaces

From Gallows to Palaces: A Social History of 50 Books EBC e-catalogue 23 June 2018 George bayntun Manvers Street • Bath • BA1 1JW • UK 01225 466000 • [email protected] www.georgebayntun.com THE COUNTESS OF LONGFORD'S COPY 1. AUSTIN (Alfred). The Garden That I Love. Woodcut illustrations. 8vo. [207 x 138 x 22 mm]. vi, 168 pp. Contemporary binding of green goatskin, the covers with an arrangement of gilt flowers with long stems. The spine divided into five panels by broad bands, lettered in the second and third panels and with the date towards the foot, and the whole spine including the bands decorated with flowers and stems, the edges of the boards tooled with a gilt fillet, the turn-ins and matching inside joints with fillets and a vine roll, plain endleaves, top edge gilt, the others uncut. [ebc2231] London: [by R. & R. Clark Ltd for] Macmillan and Co, 1898 £750 First published in 1894, this edition has "Eighth Thousand" on the title. Alfred Austin's celebration of the garden of his Kentish home, Swinford Old Manor, was immensely popular and though written in prose it led to his appointment as poet laureate in 1896. There is some light foxing but it is a delightful copy. The decoration of the spine is inspired and beautifully accomplished. Curiously the binder did not reveal his or her identity. Bookplate of Mary Longford (1877-1933), daughter of the 7th Earl of Jersey, who in 1899 married Thomas Pakenham, 5th Earl of Longford. The bookplate was designed by W.P. Barrett and dated 1906. -

Era Volume Maud, and Other Poems; and the Role of Tennyson‘S Verse Written to Mark Royal Events (Deaths, Marriages, and Anniversaries)

University of Alberta Civic Subjects: Wordsworth, Tennyson, and the Victorian Laureateship by Carmen Elizabeth Ellison A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies and Research in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English Department of English and Film Studies ©Carmen Elizabeth Ellison Fall 2010 Edmonton, Alberta Permission is hereby granted to the University of Alberta Libraries to reproduce single copies of this thesis and to lend or sell such copies for private, scholarly or scientific research purposes only. Where the thesis is converted to, or otherwise made available in digital form, the University of Alberta will advise potential users of the thesis of these terms. The author reserves all other publication and other rights in association with the copyright in the thesis and, except as herein before provided, neither the thesis nor any substantial portion thereof may be printed or otherwise reproduced in any material form whatsoever without the author's prior written permission. Examining Committee Peter W. Sinnema, English and Film Studies Susan Hamilton, English and Film Studies Christine Wiesenthal, English and Film Studies Beverly Lemire, History and Classics Lorraine Janzen Kooistra, English, Ryerson University Abstract Civic Subjects examines the ways in which poets laureate William Wordsworth and Alfred Tennyson negotiated the terrain between poetics and politics during the long reign of Queen Victoria – a period during which the monarchy was both contested (especially by popular republicanism) and in a state of transition. The first chapter traces important moments in the history of the office in Britain, both in order to establish the traditions handed down to Wordsworth and Tennyson and to clarify the office‘s complex relationships to poetics, to reading publics, to the monarchy, and to the elected government. -

Poet Laureate

THE POETS LAUREATE OF ENGLAND “I know histhry isn’t thrue, Hinnissy, because it ain’t like what I see ivry day in Halsted Street. If any wan comes along with a histhry iv Greece or Rome that’ll show me th’ people fightin’, gettin’ dhrunk, makin’ love, gettin’ married, owin’ th’ grocery man an’ bein’ without hard coal, I’ll believe they was a Greece or Rome, but not befur.” — Dunne, Finley Peter, OBSERVATIONS BY MR. DOOLEY, New York, 1902 “NARRATIVE HISTORY” AMOUNTS TO FABULATION, THE REAL STUFF BEING MERE CHRONOLOGY The Poets Laureate “Stack of the Artist of Kouroo” Project HDT WHAT? INDEX THE POETS LAUREATE OF ENGLAND 1400 Possibly as early as this year, John Gower lost his eyesight. At about this point, his CRONICA TRIPERTITA and, in English, IN PRAISE OF PEACE. Poetic praise of the new monarch King Henry IV would be rewarded with a pension paid in the form of an annual allowance of good wine from the king’s cellars.1 1. You will note that we now can denominate him as having been a “poet laureate” of England, not because he was called such in his era, for that didn’t happen, but simply because this honorable designation would eventually come to be marked by this grant of a lifetime supply of good wine from the monarch’s cellars. HDT WHAT? INDEX THE POETS LAUREATE OF ENGLAND 1591 John Wilson was born. THE SCARLET LETTER: The voice which had called her attention was that of the reverend and famous John Wilson, the eldest clergyman of Boston, a great scholar, like most of his contemporaries in the profession, and withal a man of kind and genial spirit. -

Alfred, Lord Tennyson 1 Alfred, Lord Tennyson

Alfred, Lord Tennyson 1 Alfred, Lord Tennyson The Right Honourable Lord Tennyson FRS 1869 Carbon print by Julia Margaret Cameron Born 6 August 1809 Somersby, Lincolnshire, England United Kingdom Died 6 October 1892 (aged 83) [] Lurgashall, Sussex, England United Kingdom Occupation Poet Laureate Alma mater Cambridge University Spouse(s) Emily Sellwood (m. 1850–w. 1892) Children • Hallam Tennyson (b. 11 August 1852) • Lionel (b. 16 March 1854) Alfred Tennyson, 1st Baron Tennyson, FRS (6 August 1809 – 6 October 1892) was Poet Laureate of Great Britain and Ireland during much of Queen Victoria's reign and remains one of the most popular British poets.[1] Tennyson excelled at penning short lyrics, such as "Break, Break, Break", "The Charge of the Light Brigade", "Tears, Idle Tears" and "Crossing the Bar". Much of his verse was based on classical mythological themes, such as Ulysses, although In Memoriam A.H.H. was written to commemorate his best friend Arthur Hallam, a fellow poet and fellow student at Trinity College, Cambridge, who was engaged to Tennyson's sister, but died from a brain haemorrhage before they could marry. Tennyson also wrote some notable blank verse including Idylls of the King, "Ulysses", and "Tithonus". During his career, Tennyson attempted drama, but his plays enjoyed little success. A number of phrases from Tennyson's work have become commonplaces of the English language, including "Nature, red in tooth and claw", "'Tis better to have loved and lost / Than never to have loved at all", "Theirs not to reason why, / Theirs but to do and die", "My strength is as the strength of ten, / Because my heart is pure", "To strive, to seek, to find, and not to yield", "Knowledge comes, but Wisdom lingers", and "The old order changeth, yielding place to new". -

Appointment of the City of Toronto Poet Laureate (All Wards)

CITY CLERK Clause embodied in Report No. 3 of the Economic Development and Parks Committee, as adopted by the Council of the City of Toronto at its regular meeting held on April 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, and its special meeting held on April 30, May 1 and 2, 2001. 16 Appointment of the City of Toronto Poet Laureate (All Wards) (City Council at its regular meeting held on April 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, and its special meeting held on April 30, May 1 and 2, 2001, adopted this Clause, without amendment.) The Economic Development and Parks Committee recommends the adoption of the following report (March 12, 2001) from the Commissioner of Economic Development, Culture and Tourism: Purpose: The purpose of this report is to appoint the first Poet Laureate for the City of Toronto. Financial Implications and Impact Statement: Funding for the Poet Laureate honorarium is provided by a $5,000.00 allocation from funds donated to the Public Art Reserve Fund and a $5,000.00 grant from the Canada Council for the Arts. The Chief Financial Officer and Treasurer has reviewed this report and concurs with the financial impact statement. Recommendations: It is recommended that: (1) Mr. Dennis Lee be appointed the Poet Laureate for the City of Toronto for the years 2001, 2002 and 2003, under the terms outlined in this report; and (2) the appropriate City officials be authorized and directed to take the necessary action to give effect thereto. Background: At its meeting held on July 4, 5 and 6, 2000. Council directed the Commissioner of Economic Development, Culture and Tourism to develop a plan, in partnership with the League of Canadian Poets and other community stakeholders, for the selection and appointment of a Poet Laureate for the City of Toronto in 2001. -

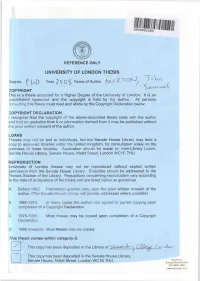

UNIVERSITY of LONDON THESIS Degree

REFERENCE ONLY UNIVERSITY OF LONDON THESIS T.U, Degree ^ | / \ f ) Year20 0$ Name of Author (KVV\ COPYRIGHT This is a thesis accepted for a Higher Degree of the University of London, It is an jnpublished typescript and the copyright is held by the author. All persons consulting this thesis must read and abide by the Copyright Declaration below. COPYRIGHT DECLARATION I recognise that the copyright of the above-described thesis rests with the author and that no quotation from it or information derived from it may be published without the prior written consent of the author. LOANS Theses may not be lent to individuals, but the Senate House Library may lend a copy to approved libraries within the United Kingdom, for consultation solely on the premises of those libraries. Application should be made to: Inter-Library Loans, Senate House Library, Senate House, Malet Street, London WC1E 7HU. REPRODUCTION University of London theses may not be reproduced without explicit written permission from the Senate House Library. Enquiries should be addressed to the Theses Section of the Library. Regulations concerning reproduction vary according to the date of acceptance of the thesis and are listed below as guidelines. A. Before 1962. Permission granted only upon the prior written consent of the author. (The Senate House Library will provide addresses where possible). B. 1962-1974. In many cases the author has agreed to permit copying upon completion of a Copyright Declaration. C. 1975-1988. Most theses may be copied upon completion of a Copyright Declaration. D. 1989 onwards. Most theses may be copied. This thesis comes within category D.