Volume 10 Issue 2 2018

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Point of Law. Comparative Legal Analysis of the Legal Status of Deputies of Belgium and France with Parliamentarians of the Russian Federation

Opción, Año 36, Especial No.27 (2020): 2157-2174 ISSN 1012-1587/ISSNe: 2477-9385 Point of Law. Comparative Legal Analysis of the Legal Status of Deputies of Belgium and France with Parliamentarians of the Russian Federation Victor Yu. Melnikov1 1Doctor of Laws. Professor of the Department of Criminal Procedure and Criminalistics Rostov Institute (branch) VGUYUA (RPA of the Ministry of Justice of Russia), Russian Federation Andrei V. Seregin2 2Associate Professor, candidate of jurisprudence, Department of theory and history of state and law, Southern Federal University, Russian Federation. Marina A. Cherkasova3 3Professor, Department of public administration, State University of management, Doctor of philosophy, Professor, Russian Federation Olga V. Akhrameeva4 4Associate Professor, candidate of jurisprudence, Department of civil law disciplines of the branch of MIREA-Russian technological University In Stavropol, Russian Federation Valeria A. Danilova5 5Associate professor, candidate of jurisprudence, Department of state and legal disciplines of the Penza state university, Russian Federation Abstract The article deals with theoretical and legal problems of constitutional guarantees of parliamentary activity on the example of Recibido: 20-12-2019 •Aceptado: 20-02-2020 2158 Victor Yu. Melnikov et al. Opción, Año 36, Especial No.27 (2020): 2157-2174 Belgium and France. The authors believe that the combination of legal guarantees with the need for legal responsibility of modern parliamentarians as representatives of the people is most harmoniously enshrined in French legislation, which is advisable to use as a model when reforming the system of people's representation of the Russian Federation. Keywords: Human rights and freedoms, Parliament, Deputies, Kingdom of Belgium, Republic of France, Constitution Punto De Ley. -

The Impact of Federalism on National Party Cohesion in Brazil

National Party Cohesion in Brazil 259 SCOTT W. DESPOSATO University of Arizona The Impact of Federalism on National Party Cohesion in Brazil This article explores the impact of federalism on national party cohesion. Although credited with increasing economic growth and managing conflict in countries with diverse electorates, federal forms of government have also been blamed for weak party systems because national coalitions may be divided by interstate conflicts. This latter notion has been widely asserted, but there is virtually no empirical evidence of the relationship or even an effort to isolate and identify the specific features of federal systems that might weaken parties. In this article, I build and test a model of federal effects in national legislatures. I apply my framework to Brazil, whose weak party system is attributed, in part, to that country’s federal form of government. I find that federalism does significantly reduce party cohesion and that this effect can be tied to multiple state-level interests but that state-level actors’ impact on national party cohesion is surprisingly small. Introduction Federalism is one of the most widely studied of political institutions. Scholars have shown how federalism’s effects span a wide range of economic, policy, and political dimensions (see Chandler 1987; Davoodi and Zou 1998; Dyck 1997; Manor 1998; Riker 1964; Rodden 2002; Ross 2000; Stansel 2002; Stein 1999; Stepan 1999; Suberu 2001; Weingast 1995). In economic spheres, federalism has been lauded for improving market competitiveness and increasing growth; in politics, for successfully managing diverse and divided countries. But one potential cost of federalism is that excessive political decentralization could weaken polities’ ability to forge broad coalitions to tackle national issues.1 Federalism, the argument goes, weakens national parties because subnational conflicts are common in federal systems and national politicians are tied to subnational interests. -

Joint Committee on Public Petitions, Houses of the Oireachtas, Republic

^<1 AM p,I , .S' Ae RECEIVED r , ,1FEB2i2{ a Co GII C' CS, I ^'b' Via t\ SGIrbhis Thith an 01 ea htais @ Houses of the Oireachtas Service TITHE AN O^REACHTAZS . AN COMHCH01STE UM ACHAINtOCHA ON bPOBAL HOUSES OF THE OrREACHTAS JOINT COMMITTEE ON PUBLIC PET^TiONS SUBM^SS^ON OF THE SECRETARIAT OF THE JOINT COMMITTEE ON PUBLIC PETITIONS - IRELAND ^NqUIRY INTO THE FUNCTIONS, PROCESSES AND PROCEDURES . OF THE STANDING COMMITrEE ON ENv^RONMENT AND PUBLrc AFFAIRS LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL WESTERN AUSTRAL^A Houses of the Oireachtas Leinster House Kildare St Dublin 2 Do2 xR2o Ireland ,.,. February 2020 II'~ API ~~ ~, I -,/' -.<,, ,:; -.. t . Contents I . I n trod u ct io n ...,............................................................................................................ 4 2. Joint Committee on Public Service Oversight and Public Petitions 2 0 I I - 2 0 I 6 ..........................................................,.,,.....,.,,.,,,....................................... 5 3. Composition, Purpose, Powers of the Joint Committee on Public Service Oversig ht a rid Pu blic Petitions 201 I- 2016. .................................... 6 3.2 The Joint sub-Committee on Pu blic Petitions 2011 '20/6 ................,..,,,. 7 3.3 The Joint Sub-Committee on the Ombudsman 2011-2016. ................... 9 4. Joint Committee on Public Petitions 2016 - 2020 ...................................,. 10 4.2. Functions of the Joint Committee on Public Petitions 201.6-2020 .... 10 4.3. Powers of the Joint Committee on Public Petitions 201.6-2020 ..... 10 Figu re I : Differences of remit between Joint Committees ........,................,. 12 5 . Ad mis si bi lity of P etitio n s ...................,.., . .................... ....,,,, ... ... ......,.,,,.,.,....... 14 5.2 . In ad missi bin ty of Petitio ns .,,,........,,,,,,,,.., ................... ..,,,........ ., .,. .................. Is 5.3. Consideration of Petitio ns by the Committee. -

KAZAKHSTAN TREND from Totalitarianism to Democratic and Legal State

Astana, 2015 ББК 63.3(5Ка)я6 С 82 Kazakhstan trend: from Totalitarianism to Democratic and Legal State (View from the Outside) / Collection of articles. Executive editor and author of the introduction Doctor of Law, professor, Honored worker of the Republic of Kazakhstan I.I. Rogov, Astana, 2015. – 234 p. ISBN 9965-27-571-8 ББК 63.3(5Ка)я6 Constitution of the Republic of Kazakhstan, drafted on the initiative and under the direct supervision of the President of the Republic of Kazakhstan – Leader of the Nation N.A. Nazarbayev, adopted on the nationwide referendum on 30 August 1995, has become a stable political and legal foundation of the state and society, dialectical combination of the best achievements of the world constitutional idea with Kazakhstan values, of the formation of unified constitutional and legal policy and practice, of gradual assertion of real constitutionalism. This publication includes articles, reflecting the opinions of foreign experts on the significance of the Constitution of the Republic of Kazakhstan in the deep and comprehensive reformation of Kazakhstan, its transformation into a modern, strong, successful and prosperous state. The collection also includes analytical comparative materials on the experience of Kazakhstani law and state institutions in comparison with similar branches and institutions of other countries. Among the authors are the representatives of authoritative international organizations, famous politicians, heads of state agencies, world-known scientists from various fields of human knowledge. Publication is interesting and useful for politicians, legislators and law enforcers, academics and wide audience. ISBN 9965-27-571-8 © Constitutional Council of the Republic of Kazakhstan, 2015 CONTENT INTRODUCTION ......................................................................................................................... -

Análisis Y Diseño

The European Centre for Parliamentary Research and Documentation (ECPRD) Cortes Generales SEMINAR EUROPEAN CORTES GENERALES - CENTRE FOR PARLIAMENTARY RESEARCH AND DOCUMENTATION (ECPRD) INFORMATION AND COMMUNICATION TECHNOLOGY AREA OF INTEREST PARLIAMENTS ON THE NET X (Madrid, Palacio del Senado, 31st May – 1st June 2012) Mobility, Transparency and open parliament: best practices in Parliamentary web sites Agenda - Thursday, 31st May 9:00 - 10:00: Registration and Accreditation of Participants. (Entrance on Bailén Street). 10:00-10:30: Official opening of the Seminar. Welcome greetings - Statement by Rosa Ripolles, ECPRD correspondent at the Congress of Deputies - Statement by Ulrich Hüschen Co-Secretary ECPRD, European Parliament - Statement by Manuel Alba Navarro, Secretary General of the Congress of Deputies - Statement by Yolanda Vicente, Second Deputy Speaker of the Senate. Carlo Simonelli, ECPRD ICT Coordinator, Chamber of Deputies, Italy; Javier de Andrés, Director TIC, Congreso de los Diputados, España and José Ángel Alonso, Director TIC, Senado, España) take the Chair The European Centre for Parliamentary Research and Documentation (ECPRD) Cortes Generales 10:30 to 12:00 Morning session 1: presentations. • Questionnaire for the ECPRD Seminar 'Parliaments on the Net X'. Miguel Ángel Gonzalo. Webmaster, Congress of Deputies. Spain • Mobility and transparency: Current status in the Congress of Deputies. Open Parliament: some remarks. Javier de Andrés. ICT Director Congress of Deputies. Spain. • New web site and mobility experience in the Senate of Spain. José Ángel Alonso ICT Director and José Luis Martínez, Analist. Senate. Spain • Debate 12:00 to 12:15 Coffee Break 12:15-13:00: Morning session (2) • Knocking on the Parliament´s door Rafael Rubio. -

The European Parliament Should Return to a 'Dual Mandate' System

The European Parliament should return to a ‘dual mandate’ system which uses national politicians as representatives instead of directly elected MEPs blogs.lse.ac.uk/europpblog/2014/06/16/the-european-parliament-should-return-to-a-dual-mandate-system- which-uses-national-politicians-as-representatives-instead-of-directly-elected-meps/ 16/06/2014 One of the key criticisms of European Parliament elections is that low turnout prevents the Parliament from genuinely being able to confer legitimacy on the EU’s legislative process. Herman Lelieveldt writes that while there was a small increase in turnout in the 2014 European elections, the overall trend of declining turnout necessitates a radical reform to improve the EU’s democratic legitimacy. He suggests returning to a ‘dual mandate’ system through which national parliaments appoint a proportion of their members to split time between the European Parliament and the national level. With a turnout that was only slightly higher than five years ago and a general consensus that many of the dissatisfied voters stayed home, the new European Parliament continues the paradoxical trend of declining legitimacy despite a systematic increase in its powers over the last decades. If it comes to mobilising more voters it is safe to conclude that the experiment with the Spitzenkandidat has been an utter failure. Apart from maybe in Germany, the contest did not generate much excitement in the member states nor did it bring more voters to the polls. Hence we are left with another election in which a majority of the member states (17 out of the 28) saw turn-out again decline, as shown in the Chart below. -

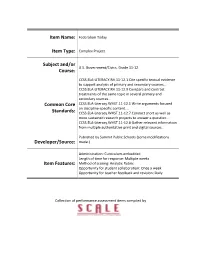

History SS Federalism Today Complex Project

Item Name: Federalism Today Item Type: Complex Project Subject and/or U.S. Government/Civics, Grade 11-12 Course: CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.RH.11-12.1 Cite specific textual evidence to support analysis of primary and secondary sources… CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.RH.11-12.9 Compare and contrast treatments of the same topic in several primary and secondary sources… Common Core CCSS.ELA-Literacy.WHST.11-12.1 Write arguments focused on discipline-specific content…. Standards: CCSS.ELA-Literacy.WHST.11-12.7 Conduct short as well as more sustained research projects to answer a question… CCSS.ELA-Literacy.WHST.11-12.8 Gather relevant information from multiple authoritative print and digital sources… Published by Summit Public Schools (some modifications Developer/Source: made.) Administration: Curriculum-embedded Length of time for response: Multiple weeks Item Features: Method of scoring: Analytic Rubric Opportunity for student collaboration: Once a week Opportunity for teacher feedback and revision: Daily Collection of performance assessment items compiled by Overview This learning module will prepare you to write an argument over which level of government, federal or state, should have the authority and power when making and executing laws on controversial issues. You will research an issue of your choice, write an argument in support of your position, and then present it to a panel of judges. Standards AP Standards: APS.SOC.9-12.I Constitutional Underpinnings of United States Government APS.SOC.9-12.I.D - Federalism Objective: Understand the implication(s) -

Report on the Foreign Policy of the Czech Republic 2007

CONTENTS INTRODUCTION......................................................................................................................6 I. MULTILATERAL COOPERATION ................................................................................. 14 1. The Czech Republic and the European Union ........................................................ 14 The Czech Republic and the EU Common Foreign and Security Policy ............. 33 The Czech Republic and European Security and Defence Policy ........................ 42 2. The Czech Republic and the North Atlantic Treaty Organisation (NATO) ............ 48 3. The Czech Republic and Regional Cooperation ..................................................... 74 Visegrad cooperation ............................................................................................. 74 Central European Initiative (CEI) .......................................................................... 78 Regional Partnership .............................................................................................. 80 Stability Pact for South East Europe ..................................................................... 82 4. The Czech Republic and other European international organisations and forums .. 84 The Czech Republic and the Organisation for Security and Cooperation in Europe (OSCE)................................................................................................................... 84 Council of Europe ................................................................................................. -

The Strange Revival of Bicameralism

The Strange Revival of Bicameralism Coakley, J. (2014). The Strange Revival of Bicameralism. Journal of Legislative Studies, 20(4), 542-572. https://doi.org/10.1080/13572334.2014.926168 Published in: Journal of Legislative Studies Queen's University Belfast - Research Portal: Link to publication record in Queen's University Belfast Research Portal Publisher rights © 2014 Taylor & Francis. This work is made available online in accordance with the publisher’s policies. Please refer to any applicable terms of use of the publisher General rights Copyright for the publications made accessible via the Queen's University Belfast Research Portal is retained by the author(s) and / or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing these publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. Take down policy The Research Portal is Queen's institutional repository that provides access to Queen's research output. Every effort has been made to ensure that content in the Research Portal does not infringe any person's rights, or applicable UK laws. If you discover content in the Research Portal that you believe breaches copyright or violates any law, please contact [email protected]. Download date:01. Oct. 2021 Published in Journal of Legislative Studies , 20 (4) 2014, pp. 542-572; doi: 10.1080/13572334.2014.926168 THE STRANGE REVIVAL OF BICAMERALISM John Coakley School of Politics and International Relations University College Dublin School of Politics, International Studies and Philosophy Queen’s University Belfast [email protected] [email protected] ABSTRACT The turn of the twenty-first century witnessed a surprising reversal of the long-observed trend towards the disappearance of second chambers in unitary states, with 25 countries— all but one of them unitary—adopting the bicameral system. -

Who Was Henry L. Shattuck?

Henry Lee Shattuck . The Research Bureau’s Public Service Awards are state and city government where his integrity and great legislators of this century on Beacon Hill. He named in honor of Henry Lee Shattuck, Chairman of reliability made him a strong moral force. had intellect, integrity and an intense devotion to the Research Bureau for 17 years, from 1942 to public service and was absolutely fearless.” No In 1908, Mr. Shattuck was elected to the 1958 and a guiding force behind the establishment Boston political figure in this century was held in Republican Ward Committee, a role he maintained of the Research Bureau in 1932. Mr. Shattuck was a higher bipartisan esteem than Henry Shattuck. for almost sixty years. He was elected to the lawyer, businessman, State Legislator and City Massachusetts House of Representatives in 1919 Even as a private citizen, Henry Shattuck remained Councillor. He personified integrity, exceptional and became a member of the House Committee of involved in public affairs and issues until his death initiative, outstanding leadership and sincere Ways and Means from 1920 through 1930, six years in 1971 at the age of ninety-one. Because of his commitment to public service. These are the of which he served as the committee chairman. interest and support, many young candidates characteristics which are represented by each founded careers in public office, enriching the fabric recipient of the Henry L. Shattuck Public Service Henry Shattuck decided not to run for reelection to of local government beyond his own lifetime. Henry Award. a seventh straight term in 1930 in order to L. -

Introduction to Volume 1 the Senators, the Senate and Australia, 1901–1929 by Harry Evans, Clerk of the Senate 1988–2009

Introduction to volume 1 The Senators, the Senate and Australia, 1901–1929 By Harry Evans, Clerk of the Senate 1988–2009 Biography may or may not be the key to history, but the biographies of those who served in institutions of government can throw great light on the workings of those institutions. These biographies of Australia’s senators are offered not only because they deal with interesting people, but because they inform an assessment of the Senate as an institution. They also provide insights into the history and identity of Australia. This first volume contains the biographies of senators who completed their service in the Senate in the period 1901 to 1929. This cut-off point involves some inconveniences, one being that it excludes senators who served in that period but who completed their service later. One such senator, George Pearce of Western Australia, was prominent and influential in the period covered but continued to be prominent and influential afterwards, and he is conspicuous by his absence from this volume. A cut-off has to be set, however, and the one chosen has considerable countervailing advantages. The period selected includes the formative years of the Senate, with the addition of a period of its operation as a going concern. The historian would readily see it as a rational first era to select. The historian would also see the era selected as falling naturally into three sub-eras, approximately corresponding to the first three decades of the twentieth century. The first of those decades would probably be called by our historian, in search of a neatly summarising title, The Founders’ Senate, 1901–1910. -

Bicameralism in the New Zealand Context

377 Bicameralism in the New Zealand context Andrew Stockley* In 1985, the newly elected Labour Government issued a White Paper proposing a Bill of Rights for New Zealand. One of the arguments in favour of the proposal is that New Zealand has only a one chamber Parliament and as a consequence there is less control over the executive than is desirable. The upper house, the Legislative Council, was abolished in 1951 and, despite various enquiries, has never been replaced. In this article, the writer calls for a reappraisal of the need for a second chamber. He argues that a second chamber could be one means among others of limiting the power of government. It is essential that a second chamber be independent, self-confident and sufficiently free of party politics. I. AN INTRODUCTION TO BICAMERALISM In 1950, the New Zealand Parliament, in the manner and form it was then constituted, altered its own composition. The legislative branch of government in New Zealand had hitherto been bicameral in nature, consisting of an upper chamber, the Legislative Council, and a lower chamber, the House of Representatives.*1 Some ninety-eight years after its inception2 however, the New Zealand legislature became unicameral. The Legislative Council Abolition Act 1950, passed by both chambers, did as its name implied, and abolished the Legislative Council as on 1 January 1951. What was perhaps most remarkable about this transformation from bicameral to unicameral government was the almost casual manner in which it occurred. The abolition bill was carried on a voice vote in the House of Representatives; very little excitement or concern was caused among the populace at large; and government as a whole seemed to continue quite normally.