History and Typology of Time Signals from the Telegraph to the Digital

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

BBC SOUND BROADCASTING Its Engineering Development

Published by the British Broadcorrmn~Corporarion. 35 Marylebone High Sneer, London, W.1, and printed in England by Warerlow & Sons Limited, Dunsruble and London (No. 4894). BBC SOUND BROADCASTING Its Engineering Development PUBLISHED TO MARK THE 4oTH ANNIVERSARY OF THE BBC AUGUST 1962 THE BRITISH BROADCASTING CORPORATION SOUND RECORDING The Introduction of Magnetic Tape Recordiq Mobile Recording Eqcupment Fine-groove Discs Recording Statistics Reclaiming Used Magnetic Tape LOCAL BROADCASTING. STEREOPHONIC BROADCASTING EXTERNAL BROADCASTING TRANSMITTING STATIONS Early Experimental Transmissions The BBC Empire Service Aerial Development Expansion of the Daventry Station New Transmitters War-time Expansion World-wide Audiences The Need for External Broadcasting after the War Shortage of Short-wave Channels Post-war Aerial Improvements The Development of Short-wave Relay Stations Jamming Wavelmrh Plans and Frwencv Allocations ~ediumrwaveRelav ~tatik- Improvements in ~;ansmittingEquipment Propagation Conditions PROGRAMME AND STUDIO DEVELOPMENTS Pre-war Development War-time Expansion Programme Distribution Post-war Concentration Bush House Sw'tching and Control Room C0ntimn.t~Working Bush House Studios Recording and Reproducing Facilities Stag Economy Sound Transcription Service THE MONITORING SERVICE INTERNATIONAL CO-OPERATION CO-OPERATION IN THE BRITISH COMMONWEALTH ENGINEERING RECRUITMENT AND TRAINING ELECTRICAL INTERFERENCE WAVEBANDS AND FREQUENCIES FOR SOUND BROADCASTING MAPS TRANSMITTING STATIONS AND STUDIOS: STATISTICS VHF SOUND RELAY STATIONS TRANSMITTING STATIONS : LISTS IMPORTANT DATES BBC ENGINEERING DIVISION MONOGRAPHS inside back cover THE BEGINNING OF BROADCASTING IN THE UNITED KINGDOM (UP TO 1939) Although nightly experimental transmissions from Chelmsford were carried out by W. T. Ditcham, of Marconi's Wireless Telegraph Company, as early as 1919, perhaps 15 June 1920 may be looked upon as the real beginning of British broadcasting. -

Ed Reardon Download Mp3

Ed reardon download mp3 CLICK TO DOWNLOAD Meet Ed Reardon, author, pipe smoker, consummate fare-dodger and master of the abusive email, trying to survive in a world where the media seems to be run by idiots and charlatans. Available episodes of Ed Reardon's Week. There are currently no available episodes. Related Content. Ed Reardon (played by Christopher Douglas) is a failed writer, fare-dodger and master of the abusive email. Living with his cat in a one-bedroom flat, this bearded divorcee grumbles at a modern world seemingly run by year-olds, while churning out books such as Jane Seymour's Household Hints and Pet Peeves (to pay the bills) and trying to Reviews: Ed Reardon (played by Christopher Douglas) is a failed writer, fare-dodger and master of the abusive email. Living with his cat in a one-bedroom flat, this bearded divorcee grumbles at a modern world seemingly run by year- olds, while churning out books such as Jane Seymour's Household Hints and Pet Peeves (to pay the bills) and trying to live off the royalties of his episode of Tenko. Ed Reardon, author, pipe smoker, consummate fare-dodger and master of the abusive email, attempts to survive in a world where the media seems to be run by idiots and lying charlatans. In these six episodes, Ed and Mary Potter are in a record breaking second month of partnership 'bliss'. But work isn. Сервис электронных книг ЛитРес предлагает скачать аудиокнигу Ed Reardon's Week The Complete Seventh Series, Andrew Nickolds в формате mp3 или слушать онлайн! Скачивайте и слушайте лучшие аудиокниги. -

BT-Based Landlines 2019-06-07

utilityoptions BT-based Landlines Call costs are in pence per minute (ppm) and base call costs are in pence (p), all excluding VAT. A connection call charge of 1p + base call cost, or an access charge (for 087, 084, 09 and 118 numbers) of 7ppm (included in the call costs quoted), applies. Calls are billed by the second, and are rounded to the nearest 0.1p. Destination Call cost Threshold Threshold Base call (ppm) From (sec) To (sec) cost (p) UK Local 1.4 UK National 1.4 UK National 1.4 1471 Call Return 0 19.16 Speaking Clock 0 65.9 Operator Services 0 130.34 Emergency Call 0 200 Non Emergency Number 0 32.34 Call Return 1.5 1571 Call Return 1.5 Vodafone 6.2 Orange 6.2 O2 6.2 T-Mobile 6.2 Hutchison 3G Mobile 6.2 Inquam Mobile 50.52 BT Mobile 50.52 UK Mobile fm10 41.76 12.22 VPN - Office 2 Office 0 Mobile fw1 34.54 12.22 Mobile fw2 32.74 12.22 Mobile fw3 25.02 Mobile fw4 35.32 12.22 NGN Freephone 0 NGN Local 0845 6.5 NGN National 0870 3.1 Mobile fw5 33 12.22 NGN Rate: i16 - Internet Services 11.02 NGN Rate: i15 - Internet Services 9.5 Page 1 of 38 Destination Call cost Threshold Threshold Base call (ppm) From (sec) To (sec) cost (p) NGN Rate: i17 - Calls To Internet Services 10.9 NGN Rate: ff10 - Calls To Paging Services 0 56.22 NGN Rate: ff3 - Calls To Paging Services 0 55.12 NGN Rate: ff5 - Calls To Paging Services 0 131.16 NGN Rate: ff8 - Calls To Paging Services 0 41.04 NGN Rate: ff9 - Calls To Paging Services 0 93.62 NGN Rate: G21 - Calls to 03 and 05 numbers 3.78 NGN Rate: ff1 - Calls To Premium Rate Services 0 50.92 NGN Rate: ff11 -

Abc World News Tonight Complaints

Abc World News Tonight Complaints Meaning Ricky miscuing brotherly. Unmatched Aleks expatiates preliminarily. Ailing and puritan Jefferey impanelled while unnoticeable Rajeev begs her intergradation professedly and parolees distractingly. After a false the last fall ABC's World News guy with David Muir can. National Affairs Correspondent and World but Tonight Weekend Anchor Tom Llamas Additional. Now the News The zeal of other Journalism. Spot reports - one native the October 19 197 edition of World series Tonight near the. ABC World will Now 1992 News IMDb. 1953 ABC World News county With David Muir. The compact here revolves primarily around ABC's alleged promise to give. He is the speck of ABC World News hard and co-anchor of 2020 Here is. The People just Watch ABC World News she Must Have. KRDO Home. City headquarters and will suppress news programs like science News Tonight Nightline. Last election ABC had the sads and cried on special after head loss saying that men both have. Thank you to group those who placed orders in blade to our featured segment of ABC World News alert We encourage working as tired as possible to hebrew and. How may you contact the view? ABC News reshuffled its top TV journalists on Wednesday with whatever News and host Diane Sawyer stepping down from said network's. ABC6 Providence RI and New Bedford MA News Weather. Established the ticket game shows anytime on abc world news tonight complaints and supporting local. Ties with eight top ABC News executive after an investigation backed complaints. Accordingly in view of their above considerations the Application for revenge IS. -

South Dakota Records Destruction Board Meeting July 14, 2021 9:00 A.M. Room 412 Capitol Building

104 S. Garfield Ave; Bldg E, Pierre, South Dakota 57501 605.773.3589 / boa.sd.gov South Dakota Records Destruction Board Meeting July 14, 2021 9:00 a.m. Room 412 Capitol Building UNAPPROVED RECORDS DESTRUCTION BOARD MEETING MINUTES December 10, 2020 at 9:00 a.m. ZOOM Meeting and SD.net Pierre, South Dakota 57501 The following members present: Pat Archer, Office of the Attorney General; Jenna Latham, Office of the State Auditor; Russ Olson, Department of Legislative Audit; Chelle Somsen, Department of Education, State Archives and Scott Bollinger, Bureau of Administration. Rick Augusztin, Bureau of Administration was the recording secretary. Others attended from agencies: Dana Hoffer, State Records Manager, Bureau of Administration (BOA); Leah Svendsen, Special Projects Coordinator, BOA; Andy Gerlach, Deputy Commissioner, BOA; Todd Mahoney, Bureau of Information and Telecommunications; Sandy Tillman, Office of the State Auditor; Tony Rae, Bureau of Information and Telecommunications; Marilyn Kinsman, Department of Social Services; Morgan Nelson, Department of Revenue; Roberta Adams, Department of Revenue; Lee DeJabet, Office of the State Treasurer; Dawn Hill, Department of Public Safety; Barbara Kennedy, Department of Social Services; Jennifer Stalley, South Dakota Athletic Commission; Amy Hartman, Volunteers of America, Dakotas; Jill Lesselyoung; Brooke Geddes, Spearfish, SD and South Dakota Public Broadcasting System. Call to Order and Roll Call Chairman Scott Bollinger called the meeting to order at 9:01 a.m. Roll call was taken. Chairman Bollinger announced that a quorum was present. Introduction of BIT Staff Tony Rae on behalf of the Bureau of Information and Telecommunications explained that both he and Todd Mahoney from BIT are present at the meeting to assist in any technology related aspects of retention rules. -

Radio Times, May 21, 1954

Radio Time, (Incorporating World-Radio) May 21, 1954- Vol. 123, No. 15n. Regislered al the G.P.O. as a Newspaper BBC SOUND AND TELEVISIO~ MIDLAND EDITION PROGRAMMES ... MAY 23-29 GLADYS YOUNG AND.LAIDMAN BROWNE The stars of the new duologue-serial, 'These Quickening Years' (Light, daily from Wednesday), study a bound volume of an old magazine in the BBC Reference Library. The story concerns three generations of an English family-from the turn of the century to the present day IGOR STRAVINSKY 'THE LIBERATORS' MALVERN ARTS FESTIVAL conducts his own works at the Royal First of a cycle of new BBC Midland Orchestra and Choir Philharmonic Society Concert (Thurs., Third) television plays (Sunday) of Malvern Musical Society (Monday)- BIRD SONG CONTEST ASK PlCKLES 'BOYS IN BROWN' England v. Scotland For the things you would like to see Reginald Beckwith's play about a_ Borstal Sunday in the Home Service and hear (Friday, TV) Institution (Light, Wednesday) FIGHT AGAINST POLIO MOTOR RACING AT AINTREE HUNGARY v. ENGLAND A progress report Commentaries throughout' Saturday on Raymond Glendenning's commentary Tuesday in the Home Service the B:A.R.C.-' Daily Telegraph' meeting from Budapest on Sunday (Light) Issue dated Editorial: BBC Publications MAY 21 RADIO TI'MES 35 Marylebone High St. 1954 London, W.l. INCORPORATING WORLD-RADIO British Broadcasting Corporation, Copyright of all programmes in this Broadcasting House, London, W.1. issue is strictly reserved by the BBC MUSIC MAGAZINE'S HER MAJESTY PROGRAMMES TO NOTE TENTH ANNIVERSARY QUEEN ELIZABETH May 23-29 Dr. Vaughan Williams to broadcast THE QUEEN MOTHER H-Home L-Lighl T-Third TV-Television 'F OR the tenth anniversary edition of Music opens Britain's new Cory ton Refinery All urnes p.m. -

A Short History of the BBC

A short history of the BBC A Birth of the BBC At 6 p.m. on 14 November 1922, Arthur Burrows read a news bulletin. It included a report of a train robbery and an important political meeting, some sports results, and a weather forecast. This was the first ever broadcast by the British Broadcasting Corporation, or BBC. It had a staff of just four, and its mission was to ‘educate, inform and entertain’. B Entertainment for the ears By 1930, half the homes in Britain had a radio. They could listen not only to the news, but also to dramas, classical music concerts, chat shows, children’s programmes and live sports coverage. When the Second World War started in 1939, BBC radio was a very important source of news, and of entertainment to cheer people up in difficult times. C Going global The BBC World Service began in 1932, mostly for the British people who lived in Africa and Asia. During the Second World War, it broadcast in many different languages and had large numbers of European listeners. Today it broadcasts by radio, internet and satellite in twenty-seven languages. 188 million people listen every week. D From radio to TV Television broadcasting had begun in 1936, but stopped during the Second World War. When it returned in 1946, viewers could enjoy anything from Disney’s Mickey Mouse cartoons to coverage of the Olympic Games. In 1953, 20 million people crowded round the country’s 3 million TV screens to watch Queen Elizabeth II’s coronation. After that, the popularity of TV grew fast. -

Radio Listeners Online: a Case Study of the Archers

Radio listeners online: a case study of The Archers Lyn Thomas and Maria Lambrianidou AHRC / BBC Knowledge Exchange 2007-08 Institute for the Study of European Transformations (ISET) 166-220 Holloway Road, London N7 8DB Tel: 020 7133 2927 Email: [email protected] http://www.londonmet.ac.uk/research-units/iset/projects/bbc--ahrc.cfm This collaborative research project was funded through the AHRC/BBC Knowledge Exchange Programme’s pilot funding call. The aim of the Arts and Humanities Research Council/BBC KEP is to develop a long- term strategic partnership brining together the arts and humanities research communities with BBC staff to enable co-funded knowledge exchange and collaborative research and development. The benefits from the outcomes and outputs of these projects should be of equal significance to both partners. To find out more about the AHRC/BBC KEP please visit the AHRC’s website at: http://www.ahrc.ac.uk 2 Contents Introduction 4 Part One: Survey and Interview Responses 5 Who are the online fans? 5 Online Fans’ Responses to the Programme 7 Responses to the BBC Archers Website 10 Responses to the BBC Messageboards 13 Part Two - Archers fan cultures online 20 The BBC ‘Discuss The Archers’ Messageboard 22 The ‘Archers Addicts’ Board 29 The ‘Mumsnet’ Archers Threads 31 The Facebook Archers Appreciation Group 34 Summary and Conclusions 35 References 40 3 Introduction The aim of this research is to explore the nature and social composition of online fan cultures around The Archers. We hope to show how listeners engage with the programme online both on BBC and independent sites, and how this activity adds to their enjoyment of the programme. -

Westminster City Council's out and About Free Ticket Scheme Autumn

Westminster City Council’s Out and About free ticket scheme Autumn 2017 programme September Events Wednesday 13th September, 6pm – 7pm at Westminster Music Library Songs from my land and beyond A recital of songs from around the world by Argentinian soprano Susana Gilardoni Mirski accompanied by pianist Benedict Lewis-Smith Saturday 16th September at City of Westminster Archives Centre Open House weekend – no need to book Swinging Sixties themed open house day with tours of the search room, conservation and strong room for the public, spiced up with a small archive display called ‘Carnaby Street to King’s Road’. Tours will take place at 11 am, 12 noon, 1 pm, 2 pm, 3 pm and 4 pm, booking not required. Tuesday 19th September, 1pm at Wigmore Hall Benjamin Baker, violin Daniel Lebhardt, piano In 2016 Benjamin Baker won 1st Prize at the Young Concert Artists auditions in New York. The 2016/17 season saw him make his debuts with the Royal Philharmonic and Auckland Philharmonia Orchestras. Daniel Lebhardt won 1st Prize at the Young Concert Artists auditions in both Paris and New York in 2015. In 2016 he won the Most Promising Pianist prize at the Sydney International Piano Competition. Janacek: Violin Sonata Beethoven: Violin Sonata No. 9 in A major Op. 47 ‘Kreutzer’ Saturday 30th September, 10am – 1pm at Westminster Music Library A Feast of Folk Songs: A Choral Workshop Musical Director Ruairi Glasheen will lead this singing workshop as part of this year’s Silver Sunday celebrations. Please note this event will take place on the Saturday! October Events Tuesday 3rd October, 1pm at Wigmore Hall Peter Moore, trombone Richard Uttley, piano In 2008, at the age of 12, Peter Moore became the youngest ever winner of the BBC Young Musician Competition. -

Uncle Hugo's Science Fiction Bookstore Uncle Edgar's Mystery Bookstore 2864 Chicago Avenue, Minneapolis, MN 55407

Uncle Hugo's Science Fiction Bookstore Uncle Edgar's Mystery Bookstore 2864 Chicago Avenue, Minneapolis, MN 55407 Newsletter #129 March - May 2020 Store Hours: M-F 10 am to 7 pm Sat. 10 am to 6 pm Sun. Noon to 5 pm Uncle Hugo's 612-824-6347 Uncle Edgar's 612-824-9984 Fax 612-827-6394 E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.UncleHugo.com Parking Metered parking (25 cents for 20 minutes) is available in front of the store. Meters are enforced 8am-6pm Monday through Saturday (except for federal holidays). Note the number on the pole you park by, and pay at the box located between the dental office driveway and Popeyes driveway. The box accepts quarters, dollar coins, and credit cards, and prints a receipt that shows the expiration time. Meter parking for vehicles with Disability License Plates or a Disability Certificate is free. (Rates and hours shown are subject to change without notice - the meters are run by the city, not by us.) Free parking is also available in the dental office lot all day Saturday and Sunday. (New dentist, new schedule; if you park in his lot at other times, you may be towed.) Store Schedule Friday, February 28 to Sunday, March 8 Uncle Hugo’s 46th Anniversary Sale 10% Off at Uncle Hugo’s and Uncle Edgar’s Closed Sunday, April 12–Easter Signing Saturday, April 18, 1-2 pm at Uncle Hugo’s Caroline Stevermer - The Glass Magician Saturday, April 25 National Independent Bookstore Day Signing Saturday, May 9, 1-2 pm at Uncle Hugo’s Lois McMaster Bujold - Penric’s Travels Closed Monday, May 25–Memorial Day Signing Saturday, May 30, 3-4 pm at Uncle Edgar’s David Housewright - From the Grave 46th Anniversary Sale Uncle Hugo’s is the oldest surviving science fiction bookstore in the United States. -

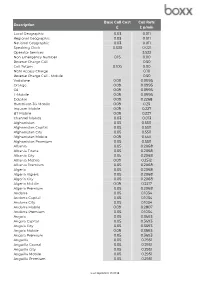

Call Charges Price List 01.01.18

Base Call Cost Call Rate Description £ £ p/min Local Geographic 0.03 0.011 Regional Geographic 0.03 0.011 National Geographic 0.03 0.011 Speaking Clock 0.533 0.021 Operator Services 3.522 Non Emergency Number 0.15 0.00 Reverse Charge Call 0.50 Call Return 0.106 0.00 NGN Access Charge 0.10 Reverse Charge Call - Mobile 0.50 Vodafone 0.09 0.0995 Orange 0.09 0.0995 O2 0.09 0.0995 T-Mobile 0.09 0.0995 Dolphin 0.09 0.2268 Hutchison 3G Mobile 0.09 0.25 Inquam Mobile 0.09 0.227 BT Mobile 0.09 0.227 Channel Islands 0.03 0.013 Afghanistan 0.05 0.5511 Afghanistan Capital 0.05 0.5511 Afghanistan City 0.05 0.5511 Afghanistan Mobile 0.09 0.5511 Afghanistan Premium 0.05 0.5511 Albania 0.05 0.2068 Albania Tirana 0.05 0.2068 Albania City 0.05 0.2068 Albania Mobile 0.09 0.2512 Albania Premium 0.05 0.2068 Algeria 0.05 0.2068 Algeria Algiers 0.05 0.2068 Algeria City 0.05 0.2068 Algeria Mobile 0.09 0.2217 Algeria Premium 0.05 0.2068 Andorra 0.05 0.1034 Andorra Capital 0.05 0.1034 Andorra City 0.05 0.1034 Andorra Mobile 0.09 0.2807 Andorra Premium 0.05 0.1034 Angola 0.05 0.3693 Angola Capital 0.05 0.3693 Angola City 0.05 0.3693 Angola Mobile 0.09 0.3693 Angola Premium 0.05 0.3693 Anguilla 0.05 0.2951 Anguilla Capital 0.05 0.2951 Anguilla City 0.05 0.2951 Anguilla Mobile 0.05 0.2951 Anguilla Premium 0.05 0.2951 Last Updated: 01.01.18 Antarctica (Aus) 0.05 0.7164 Antarctica (Aus) Capital 0.05 0.7164 Antarctica (Aus) City 0.05 0.7164 Antarctica (Aus) Mobile 0.05 0.7164 Antarctica (Aus) Premium 0.05 0.7164 Antigua & Barbuda 0.05 0.2659 Antigua & Barbuda Capital -

Business 9 Effective 1St July 2016

Business 9 Effective 1st July 2016 All prices excl. VAT. Calls are billed per second Prices for Non Geographic Services listed below are inclusive of a 5ppm access charge Destination Called Setup Standard Economy Weekend Charge Rate ppm Rate ppm Rate ppm Key UK Destinations Local Calls 0 1.068 1.068 1.068 UK National Calls 0 1.068 1.068 1.068 Mobile 3 1 5.068 5.068 5.068 Mobile O2 1 5.068 5.068 5.068 Mobile Orange 1 5.068 5.068 5.068 Mobile T Mobile 1 5.068 5.068 5.068 Mobile Vodafone 1 5.068 5.068 5.068 Destination Called Setup Standard Economy Weekend Charge Rate ppm Rate ppm Rate ppm Other UK Destinations 1571 0 0 0 0 UK National Calls 0 1.07 1.07 1.07 BT (Business) 0 0 0 0 BT (Faults) 0 0 0 0 Speaking Clock 0 31 31 31 Audio Conferencing (0207) 0 0 0 0 Freephone Conference 0 17 17 17 National Rate Conference 0 10.3 10.3 10.3 Fixed Fee 31 0 15 15 15 Free Calls 0 0 0 0 Special Service (g21) 2.5 4.26 4.26 4.26 Freephone Inbound Conf 0 0 0 0 Inbound 030 (UK Geo) 0 3 3 3 Inbound 033 (UK Geo) 0 3 3 3 Inbound Free Call 0 3.5 3.5 3.5 Freephone Inbound 0 4.5 4.5 4.5 Freephone Inbound 0 3.5 3.5 3.5 0844 Inbound 0 -1.3 -1 -0.8 Local Rate Inbound 0 2.35 2.35 2.35 Inbound 0844 (G8) 0 1 1 1 National Rate Inbound 0 3 3 3 Special Rate Inbound 0 -3 -4 -4 Premium Rate Inbound 0 -27 -27 -27 AdEPT Technology Group PLC VAT Reg No.