Trent–Severn Waterway

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Victoria County Centennial History F 5498 ,V5 K5

Victoria County Centennial History F 5498 ,V5 K5 31o4 0464501 »» By WATSON KIRKCONNELL, M. A. PRICE $2.00 0U-G^5O/ Date Due SE Victoria County Centennial History i^'-'^r^.J^^, By WATSON KIRKCONNELL, M. A, WATCHMAN-WARDER PRESS LINDSAY, 1921 5 Copyrighted in Canada, 1921, By WATSON KIRKCONNELL. 0f mg brnttf^r Halter mtfa fell in artton in ttje Sattte nf Amiena Angnfit 3, ISiB, tlfia bnok ia aflfertinnatelg in^^iratei. AUTHOR'S PREFACE This history has been appearing serially through the Lindsaj "Watchman-Warder" for the past eleven months and is now issued in book form for the first time. The occasion for its preparation is, of course, the one hundredth anniversary of the opening up of Victoria county. Its chief purposes are four in number: — (1) to place on record the local details of pioneer life that are fast passing into oblivion; (2) to instruct the present generation of school-children in the ori- gins and development of the social system in which they live; (3) to show that the form which our county's development has taken has been largely determined by physiographical, racial, social, and economic forces; and (4) to demonstrate how we may, after a scien- tific study of these forces, plan for the evolution of a higher eco- nomic and social order. The difficulties of the work have been prodigious. A Victoria County Historical Society, formed twenty years ago for a similar purpose, found the field so sterile that it disbanded, leaving no re- cords behind. Under such circumstances, I have had to dig deep. -

Peterborough Campbellford Trent River Kingston Otonabee River Bay of Quinte Frankford Route 81 Rice Lake

From an idea on a rented houseboat in 1981, Lloyd and Helen Ackert and their family created Ontario Waterway Cruises Inc. Success has flourished due largely to the personal interest and enthusiasm of a family operated business. In 1993, Lloyd and Helen retired. Two of their sons, Marc and John alternate as captain aboard ship. Marc/Robin and John/Joy share the various responsibilities of managing the business. Robin manages the hospitality functions and Joy manages reservations. The history of this successful cruise operation for older adults can be found in the ship’s library. Passengers enjoy browsing the albums which trace its development from the time that this former farm family from Bruce County first “put to sea”! Helen’s ten year legacy of ship’s menu and recipes has been printed in her cookbook, and is available to passengers on board ship. 2 3 OTTAWA RIVER OTTAWA LONG ISLAND RIDEAU RIVER BURRITTS RAPIDS RIDEAU MERRICKVILLE CANAL POONAMALIE BIG CHUTE SMITHS FALLS SEVERN RIVER PORT RIDEAU STANTON GEORGIAN LAKES BAY TRENT-SEVERN WATERWAY WESTPORT KAWARTHA LAKES ORILLIA ROSEDALE BOBCAYGEON BUCKHORN KIRKFIELD ST. LAWRENCE RIVER LAKE SIMCOE TALBOT RIVER JONES FALLS LAKEFIELD GANANOQUE HEALEY FALLS HASTINGS PETERBOROUGH CAMPBELLFORD TRENT RIVER KINGSTON OTONABEE RIVER BAY OF QUINTE FRANKFORD ROUTE 81 RICE LAKE WATERTOWN, NY LAKE ONTARIO PICTON Canal Cruising Ontario is blessed with 435 miles of spectacular inland waterways: the Trent- Severn Waterway from Georgian Bay to Trenton; the Bay of Quinte and Long Reach from Trenton to Kingston; and the Rideau Canal from Kingston to Ottawa. Ontario Waterway Cruises provide canal cruising on the Kawartha Voyageur covering these waters in three 5 day segments: Big Chute to Peterborough 240 km (150 miles) and 22 locks; Peterborough to Kingston 370 km (231 miles) and 19 locks; Kingston to Ottawa 199 km (124 miles) and 35 locks. -

3146 Snowmobile Association

THE CORPORATION OF THE COUNTY OF HALIBURTON BY-LAW NUMBER 3146 A BY-LAW TO AUTHORIZE AN AGREEMENT WITH THE ONTARIO FEDERATION OF SNOWMOBILE CLUBS AND ITS MEMBERS UNDER THE DIRECT SUPERVISION OF THE HALIBURTON COUNTY SNOWMOBILE ASSOCIATION WHEREAS Section 7(4) of the Motorized Snow Vehicles Act, R.S.O. 1990, Chapter M.44 as amended provides that the council of an upper-tier municipality may pass bylaws regulating and governing the operation of a motorized snow vehicles along or across any highway or part ofa highway under its jurisdiction; and WHEREAS the County of Haliburton owns the former railway right-of way that lies within the boundaries of the County of Haliburton between the Village of Haliburton and the south boundary of the County at the Village of Kinmount known as the Haliburton County Rail Trail as described in Schedule A attached to and forming part ofthis Bylaw; and WHEREAS the County ofHaliburton is desirous ofgranting permission to the Ontario Federation of Snowmobile Clubs and its members under the direction supervision of the Haliburton County Snowmobile Association to legally enter and use the Haliburton County Rail Trail as described in Schedule "A" attached to and forming part of this Bylaw subject to certain conditions as outlined in Schedule "B" attached to and forming part ofthis Bylaw. NOW THEREFORE THE COUNCIL OF THE CORPORATION OF THE COUNTY OF HALIBURTON ENACTS AS FOLLOWS: 1. Definitions (a) Motorized Snow Vehicle means a selfpropelled vehicle designed to be driven primarily on snow. 2. The Warden and the Clerk are hereby authorized to grant permission to the Ontario Federation ofSnowmobile Clubs and its members under the direction supervision ofthe Haliburton County Snowmobile Association to legally enter and use the Haliburton County Rail Trail as described in Schedule A attached to and forming part ofthis Bylaw. -

Haggas Water Elevator"

PRESENTED BY . - . .. ..... .....,.. T::a=E : .. : . :: :.: : : :.::. .. .... ... ...... .. For Supplying Locomotive Tenders with Water. WM. GOODERHAM, JR., Managing Director Toronto & Nipissing Railway. TORONTO: G. C. Patterson & Co's Steam Print, 48..KinglSt. East. 1880. 'W\1 RAI L=xrAY S ON WHICH THE "HAGGAS WATER ELEVATOR" IS USED THROUGHOUT, WITH THE EXCEPTIONS NOTED. IN.OANADA:; BELLEVILLE, NORTH HASTINGS & GRAND JUNCTION. (Operated last season by the Grand Trunk Railway Company). CANADA PACIFIC. (170 miles west of Thunder Bay). COBOURG, PETERBORO' & MARMORA. CREDIT VALLEY. HALIFAX & CAPE BRETON. MIDLAND OF CANAD,A. NORTHERN & NORTH-WESTERN. (In part). PORT DOVER, STRATFORD & LAKE HURON. PRINCE EDWARD ISLAND. PRINCE EDWARD COUNTY. TORONTO & NIPISSING. TORONTO, GREY & BRUCE. VICTORIA. WESTERN COUNTIES. WHITBY, PORT PERRY & LINDSAY. In the United States: DETROIT, MACKINAC & MARQUETTE. CHICAGO & ATLANTIC. JERSEY CITY & ALBANY. NEW YORK, ONTARIO & WESTERN. (In part.) SUSSEX. WARWICK VALLEY. THE " HAGGAS WATER ELEVATOR," -BY WHICH- Locomotive Tenders may be supplied with water from underground cisterns at the smallest possible cost. THE· FOLLOWING CIRCULAR LETTER Contains full information with respect to the "HAGGAS WATER ELEVATOR," and its careful perusal is, there fore, earnestiy requested: TORONTO & NIPISSING RAILWAY, MANAGING DIRECTOR'S OFFICE, TORONTO, ONT., Oct. 15th, 1880. SIR,-I beg respectfully to bring under your notice, and to submit for your consideration, with a view to its use, the practical " and valuable device known -

SFNOC EVENT CALENDAR June 1 2020 to September 30 2020 MULTI-DAY EVENTS

SFNOC EVENT CALENDAR June 1 2020 to September 30 2020 MULTI-DAY EVENTS •Tuesday June 9 2020 - Friday June 12 2020 Multi-day Cycling, Prince Edward County •Tuesday August 4 2020 - Thursday August 6 2020 Multi-day Cycling: Rail trails around Peterborough. •Monday September 7 2020 - Friday September 11 2020 Camp ~ Canoe Depot Lakes near Kingston •Monday September 21 2020 - Friday September 25 2020 Multi-day Paddling: Trent-Severn Waterway Leg 3, Lock 35 Rosedale to Lock 27 Young’s Point SINGLE DAY EVENTS •Tuesday June 2 2020 Canoe Day Trip - Beaver River •Thursday June 4 2020 Cycle - Dundas to Brantford return on rail trail - 60kms •Sunday June 7 2020 Team SFNOC - Manulife Ride For Heart •Tuesday June 9 2020 Canoe, Nottawasaga River, Edenvale to Wasaga Sports Park •Thursday June 11 2020 Cycle Taylor Creek to Lake Ontario return •Tuesday June 16 2020 Scugog Country Cruise •Thursday June 18 2020 Islington Murals Walk •Tuesday June 23 2020 Parks and Art, Toronto Music Garden Walk •Thursday June 25 2020 Tortoise Cycle ~ Betty Sutherland Trail •Thursday July 2 2020 Canoe ~ Guelph Lake •Tuesday July 7 2020 Trent Waterway Kirkfield Lift Lock 36 to Rosedale Lock 35 •Wednesday July 8 2020 Pearson Airport tour •Thursday July 9 2020 Cycle ~ Oshawa Creek Bike Path •Tuesday July 14 2020 Tuesday July 14 – Walk the Toronto Zoo with an Insider •Thursday July 16 2020 Canoe ~ Toronto Islands •Tuesday July 21 2020 Canoe Muskoka River •Thursday July 23 2020 Cycle ~ Nokiidaa (Tom Taylor) Bike Trail •Tuesday July 28 2020 Canoe Emily Creek •Thursday July 30 2020 -

Kinmount Gazette

Kinmount Gazette KINMOUNT 150TH ANNIV ERSARY COMMITTEE A S U B - COMMITTEE OF T HE KINMOUNT COMMITTEE FOR PLANNING AND ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT August 5, 2009 Volume 1: Issue 10 The Victoria Railway Inside this issue: Railways: the stuff of leg- Never heard of those two or two would be just the ticket ends. In Canada, railways are “vanished” hamlets? to prosperity. NEIGHBOURS AND FRIENDS 2 a part of our history, in- Kinmount is still around The first railway to penetrate grained in our culture, legen- because it had the railway and our area was the Toronto- LEGENDS 5 dary chapters of the Cana- they didn‟t! Nippissing Railway. It origi- dian Experience. Railways Railways were common in nated in Toronto and extended KINMOUNT STATION 6 transformed the scattered & Ontario by the 1850s. It was a north-east through Uxbridge to isolated colonies of British noted fact the iron horse Coboconk. Plans called for SPOT THE SHOT 7 RECAPTURED North America into the coun- brought prosperity to any com- this line to carry on to the try called Canada. They were munity it graced. Lindsay & Nipissing District near North KINMOUNT KIDS’ CORNER 10 the “National Dream”. Peterborough both became Bay. The rails reached the Railways were the National railway towns by 1860. But banks of the Gull River in THE HOT STOVE 11 Dream for the village of Kin- railways, like roads, func- 1872: and never went any fur- mount as well in the 1800s. tioned better with more con- ther. The TNN railway dead- EDITORIAL 15 Before the Victoria Railway nections. -

Navigation Canals

Rideau Indian and Affaires indiennes Navigation Northern Affairs et du Nord Trent Parks Canada Parcs Canada Canals Québec Cover: Between locks 22 and 23 St. Peters in the second basin at Merrickville on the Rideau Canal. Navigation Canals Rideau Trent Québec St. Peters Published by Parks Canada under authority of the Hon. Warren Allmand, Minister of Indian and Northern Affairs, Ottawa, 1977 QS-1194-000-BB-A5 ©Minister of Supply and Services Canada 1977 Catalogue No. R58-2/1977 ISBN 0-662-00816-2 3 CONTENTS SECTION SUB-SECTION DESCRIPTION PAGE Inside front cover Location of Navigation Canals 1 GENERAL INFORMATION 4 1—1 Introduction 4 1—2 Location 4 1—3 Navigation Charts 4 1—4 Canal Vessel Permits and Tolls 4 2 CRUISING INFORMATION APPLICABLE TO ALL THE CANAL SYSTEMS 5 2—1 Canal Regulations 5 2—2 Licensing of Vessels 5 2—3 Speed Limits 5 2—4 Limiting Dimensions 5 2—5 Vessel Clearances 5 2—6 Comments 5 2—7 Clearance Papers 5 2—8 Approach Wharves 5 2—9 Aids to Navigation 6 2—10 Signals for Locks and Bridges 6 2-11 Power Outlets 6 2-12 Ships' Reports 6 2-13 Pollution 6 2—14 Boat Campers 6 2-15 Weed Obstructions 6 2—16 Literature Published by the Provincial Governments 6 2—17 Fire Prevention 6 3 TRENT CANAL SYSTEM 7 3-1 Charts 7 3-2 Storms and Squalls —Lake Simcoe and Lake Couchiching 7 3-3 Big Chute Marine Railway 7 3-4 Channel below Big Chute, Mile 232.5 7 3-5 Traffic Lights 7 3-6 Radio Stations 7 3-7 Canal Lake and Mitchell Lake 7 3-8 Mileage and General Data 8-13 4 RIDEAU CANAL SYSTEM 15 4-1 Charts 15 4-2 Traffic Lights 15 4-3 Radio Stations 15 4-4 Mileage and General Data 16-19 5 QUEBEC CANALS 21 5-1 Charts 21 5-2 Radio Stations 21 5-3 Richelieu River Route 21 5-4 Montréal-Ottawa Route 21 5-5 Mileage and General Data 24 6 ATLANTIC OCEAN TO BRAS D'OR LAKES ROUTE 27 6-1 St. -

California State Railroad Museum Railroad Passes Collection MS 855MS 855

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/c89g5tx2 No online items Guide to the California State Railroad Museum Railroad Passes Collection MS 855MS 855 CSRM Library & Archives Staff 2019 California State Railroad Museum Library & Archives 2019 Guide to the California State MS 855 1 Railroad Museum Railroad Passes Collection MS 855MS 855 Language of Material: English Contributing Institution: California State Railroad Museum Library & Archives Title: California State Railroad Museum Railroad Passes Collection Identifier/Call Number: MS 855 Physical Description: 12 Linear Feet(12 postcard boxes) Date (inclusive): 1856-1976 Abstract: The CSRM Passes collection consists of railroad passes that were used by railroad employees and their families to travel for free. The passes vary geographically to include railroads across the United States as well as from the late 1850s through the 1970's. The collection has been developed by donations from individuals who believed the passes had relevance to railroads and railroading. Language of Material: English Statewide Musuem Collection Center Conditions Governing Access Collection is open for research by appointment Other Finding Aids See also MS 536 Robert Perry Dunbar passes and cards Preferred Citation [Identification of item], California State Railroad Museum Railroad Passes Collection, MS 855, California State Railroad Museum Library and Archives, Sacramento, California. Scope and Contents The CSRM Passes collection consists of railroad passes that were used by railroad employees and their families to travel for free. The passes vary geographically to include railroads from across the United States as well as from the late 1850's through the 1970's. Many of the passes are labeled the names of employees as well as their family members who are entitled to the usage of the pass. -

Trent-Severn & Lake Simcoe

MORE THAN 200 NEW LABELED AERIAL PHOTOS TRENT-SEVERN & LAKE SIMCOE Your Complete Guide to the Trent-Severn Waterway and Lake Simcoe with Full Details on Marinas and Facilities, Cities and Towns, and Things to Do! LAKE KATCHEWANOOKA LOCK 23 DETAILED MAPS OF EVERY Otonabee LOCK 22 LAKE ON THE SYSTEM dam Nassau Mills Insightful Locking and Trent University Trent Boating Tips You Need to Know University EXPANDED DINING AND OTONABEE RIVER ENTERTAINMENT GUIDE dam $37.95 ISBN 0-9780625-0-7 INCLUDES: GPS COORDINATES AND OUR FULL DISTANCE CHART 000 COVER TS2013.indd 1 13-04-10 4:18 PM ESCAPE FROM THE ORDINARY Revel and relax in the luxury of the Starport experience. Across the glistening waters of Lake Simcoe, the Trent-Severn Waterway and Georgian Bay, Starport boasts three exquisite properties, Starport Simcoe, Starport Severn Upper and Starport Severn Lower. Combining elegance and comfort with premium services and amenities, Starport creates memorable experiences that last a lifetime for our members and guests alike. SOMETHING FOR EVERYONE… As you dock your boat at Starport, step into a haven of pure tranquility. Put your mind at ease, every convenience is now right at your fi ngertips. For premium members, let your evening unwind with Starport’s turndown service. For all parents, enjoy a quiet reprieve at Starport’s on-site restaurants while your children are welcomed and entertained in the Young Captain’s Club. Starport also offers a multitude of invigorating on-shore and on-water events that you can enjoy together as a family. There truly is something for everyone. -

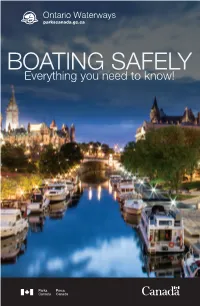

BOATING SAFELY Everything You Need to Know!

boatingsafelycover2014_en.pdf 1 18/02/2014 5:16:49 PM Ontario Waterways parkscanada.gc.ca BOATING SAFELY Everything you need to know! C M Y CM MY CY CMY K Boating Safely 2011 Eng final:Boating Safely update#1DC3E.qxd 07/03/11 3:20 PM Page 2 THE RIDEAU CANAL NATIONAL HISTORIC SITE AND THE TRENT–SEVERN WATERWAY NATIONAL HISTORIC SITE are historic canals operated by Parks Canada, an agency of the Department of the Environment. They are part of a large family of national parks and national historic sites located across the country. These historic canals are popular waterways that cater to recreational boaters, including canoeists and kayakers, as well as land-based visitors. If you are locking through or just visiting a lock station, the friendly lock staff are available to answer your questions, explain lock operations and offer you further assistance. This guide is designed to help make your passage through the two systems a safe and enjoyable experience. BEFORE YOU CAST OFF WIND, WATER AND WEATHER combine to test your skill as a boater. Checking the latest marine weather forecast for your area should always be a priority before heading out on the water. All Environment Canada weather offices offer a 24 hour-a-day automated telephone service that provides the most recent forecast information. Their locations include: Ottawa 613-998-3439 Peterborough 705-743-5852 Kingston 613-545-8550 Collingwood 705-446-0711 or check www.weatheroffice.ec.gc.ca. Marine weather forecasts are sometimes included in these messages during the navigation season. RADIO STATION WEATHER BROADCASTS MANY COMMERCIAL FM AND AM radio stations along the Trent– Severn Waterway and the Rideau Canal broadcast marine weather forecasts during the navigation season. -

Canadian Rail No156 1964

c;an..adian.. )~~fin Number 156 / June 1964 :Belf£il, June 29, 1864. mlRECISELY one hundred years ago this month, on June 29th, g 1864, a special passenger train on the Grand Trunk Rail- way of Canada, carrying three hundred and fifty German immigrants, went through an open drawbridge at the village of Beloeil, Que., thus precipitating Canada's worst railway accident. Ninety seven immigrants, the conductor and the locomotive fire man and, two days later, a curious onlooker, succumbed, carrying the death toll up to an even one hundred. The passengers had come from Europe on the salling vessel "Neckar", disembarked at Quebec, and were ferried to Levis where they were loaded on the ill-fated train. which consisted of two baggage cars, seven cars normally used for produce but tem porarily fitted up for passengers, a second-class coach and a brake van. The train was pulled by the 4-4-0 locomotiv .. "HAM", No. 168 of the G. T. R .. a product of the works of D.C.Gunn at Hamilton. Special trains had depleted the supply of engine- and train-crew at Richmond, the intermediate divisional point between Levis and Montreal, and the locomotive foreman persuaded Will iam Burney, a newly-promoted engine driver. to take the train to Montreal, even though he had never operated a locomotive over the section. Conductor. fireman and brakeman completed the crew. Approaching the Richelieu River bridge between St. Hilaire and Beloeil at about 1 :15 AM, the train failed to make a mandat ory stop at the east end of the bridge, provided for in the Company rules. -

Provincial Plaques Across Ontario

An inventory of provincial plaques across Ontario Last updated: May 25, 2021 An inventory of provincial plaques across Ontario Title Plaque text Location County/District/ Latitude Longitude Municipality "Canada First" Movement, Canada First was the name and slogan of a patriotic movement that At the entrance to the Greater Toronto Area, City of 43.6493473 -79.3802768 The originated in Ottawa in 1868. By 1874, the group was based in Toronto and National Club, 303 Bay Toronto (District), City of had founded the National Club as its headquarters. Street, Toronto Toronto "Cariboo" Cameron 1820- Born in this township, John Angus "Cariboo" Cameron married Margaret On the grounds of his former Eastern Ontario, United 45.05601541 -74.56770762 1888 Sophia Groves in 1860. Accompanied by his wife and daughter, he went to home, Fairfield, which now Counties of Stormont, British Columbia in 1862 to prospect in the Cariboo gold fields. That year at houses Legionaries of Christ, Dundas and Glengarry, Williams Creek he struck a rich gold deposit. While there his wife died of County Road 2 and County Township of South Glengarry typhoid fever and, in order to fulfil her dying wish to be buried at home, he Road 27, west of transported her body in an alcohol-filled coffin some 8,600 miles by sea via Summerstown the Isthmus of Panama to Cornwall. She is buried in the nearby Salem Church cemetery. Cameron built this house, "Fairfield", in 1865, and in 1886 returned to the B.C. gold fields. He is buried near Barkerville, B.C. "Colored Corps" 1812-1815, Anxious to preserve their freedom and prove their loyalty to Britain, people of On Queenston Heights, near Niagara Falls and Region, 43.160132 -79.053059 The African descent living in Niagara offered to raise their own militia unit in 1812.