The Date When Hamlet Was Written Has Always Been Problematic And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bibliography for the Study of Shakespeare on Film in Asia and Hollywood

CLCWeb: Comparative Literature and Culture ISSN 1481-4374 Purdue University Press ©Purdue University Volume 6 (2004) Issue 1 Article 13 Bibliography for the Study of Shakespeare on Film in Asia and Hollywood Lucian Ghita Purdue University Follow this and additional works at: https://docs.lib.purdue.edu/clcweb Part of the Comparative Literature Commons, and the Critical and Cultural Studies Commons Dedicated to the dissemination of scholarly and professional information, Purdue University Press selects, develops, and distributes quality resources in several key subject areas for which its parent university is famous, including business, technology, health, veterinary medicine, and other selected disciplines in the humanities and sciences. CLCWeb: Comparative Literature and Culture, the peer-reviewed, full-text, and open-access learned journal in the humanities and social sciences, publishes new scholarship following tenets of the discipline of comparative literature and the field of cultural studies designated as "comparative cultural studies." Publications in the journal are indexed in the Annual Bibliography of English Language and Literature (Chadwyck-Healey), the Arts and Humanities Citation Index (Thomson Reuters ISI), the Humanities Index (Wilson), Humanities International Complete (EBSCO), the International Bibliography of the Modern Language Association of America, and Scopus (Elsevier). The journal is affiliated with the Purdue University Press monograph series of Books in Comparative Cultural Studies. Contact: <[email protected]> Recommended Citation Ghita, Lucian. "Bibliography for the Study of Shakespeare on Film in Asia and Hollywood." CLCWeb: Comparative Literature and Culture 6.1 (2004): <https://doi.org/10.7771/1481-4374.1216> The above text, published by Purdue University Press ©Purdue University, has been downloaded 2531 times as of 11/ 07/19. -

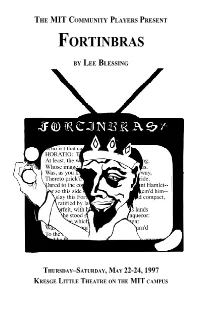

Fortinbras Program

THE MIT COMMUNITY PLAYERS PRESENT FORTINBRAS BY LEE BLESSING THURSDAY–SATURDAY, MAY 22-24, 1997 KRESGE LITTLE THEATRE ON THE MIT CAMPUS FORTINBRAS by Lee Blessing *Produced by special arrangement with Baker’s Plays The Persons of the Play Fortinbras ...................................... Steve Dubin Hamlet ........................................... Greg Tucker (S) Osric .............................................. Ian Dowell (A) Horatio........................................... Matt Norwood ’99 Ophelia .......................................... Erica Klempner (G) Claudius ........................................ Ben Dubrovsky (A) Gertrude ........................................ Anne Sechrest (affil) Laertes .......................................... Randy Weinstein (G) Polonius......................................... Peter Floyd (A, S) Polish Maiden 1............................. Alice Waugh (S) Polish Maiden 2............................. Anna Socrates Captain .......................................... Jim Carroll (A) English Ambassador ..................... Alice Waugh (S) Marcellus....................................... Eric Lindblad (G) Barnardo ....................................... Russell Miller ’00 The Scenes of the Play Act I: Elsinore — ten minute intermission — Act II: Still Elsinore (“S” indicates MIT staff member, “G” indicates graduate student, “A” indicates alumnus, and “affil” indicates affiliation with a member of the MIT community). Behind the Scenes Director............................................. Ronni -

The Tragedy of Hamlet

THE TRAGEDY OF HAMLET THE WORKS OF SHAKESPEARE THE TRAGEDY OF HAMLET EDITED BY EDWARD DOWDEN n METHUEN AND CO. 36 ESSEX STREET: STRAND LONDON 1899 9 5 7 7 95 —— CONTENTS PAGE Introduction ix The Tragedy of Hamlet i Appendix I. The "Travelling" of the Players. 229 Appendix II.— Some Passages from the Quarto of 1603 231 Appendix III. Addenda 235 INTRODUCTION This edition of Hamlet aims in the first place at giving a trustworthy text. Secondly, it attempts to exhibit the variations from that text which are found in the primary sources—the Quarto of 1604 and the Folio of 1623 — in so far as those variations are of importance towards the ascertainment of the text. Every variation is not recorded, but I have chosen to err on the side of excess rather than on that of defect. Readings from the Quarto of 1603 are occa- sionally given, and also from the later Quartos and Folios, but to record such readings is not a part of the design of this edition. 1 The letter Q means Quarto 604 ; F means Folio 1623. The dates of the later Quartos are as follows: —Q 3, 1605 161 1 undated 6, For ; Q 4, ; Q 5, ; Q 1637. my few references to these later Quartos I have trusted the Cambridge Shakespeare and Furness's edition of Hamlet. Thirdly, it gives explanatory notes. Here it is inevitable that my task should in the main be that of selection and condensation. But, gleaning after the gleaners, I have perhaps brought together a slender sheaf. -

An Analysis of Paternal Models of Authority and Filial Duty in Shakespeare’S Hamlet

The Dilemma of Shakespearean Sonship: An Analysis of Paternal Models of Authority and Filial Duty in Shakespeare’s Hamlet The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Mosley, Joseph Scott. 2017. The Dilemma of Shakespearean Sonship: An Analysis of Paternal Models of Authority and Filial Duty in Shakespeare’s Hamlet. Master's thesis, Harvard Extension School. Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:33826315 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA The Dilemma of Shakespearean Sonship: An Analysis of Paternal Models of Authority and Filial Duty in Shakespeare’s Hamlet Joseph Scott Mosley A Thesis in the Field of Dramatic Arts for the Degree of Master of Liberal Arts in Extension Studies Harvard University May 2017 © 2017 Joseph Scott Mosley Abstract The aim of the proposed thesis will be to examine the complex and compelling relationship between fathers and sons in Shakespeare’s Hamlet. This study will investigate the difficult and challenging process of forming one’s own identity with its social and psychological conflicts. It will also examine how the transformation of the son challenges the traditional family model in concert or in discord with the predominant philosophy of the time. I will assess three father-son relationships in the play – King Hamlet and Hamlet, Polonius and Laertes, and Old Fortinbras and Fortinbras – which thematize and explore filial ambivalence and paternal authority through the act of revenge and mourning the death of fathers. -

POLITICS, SOCIETY and CIVIL WAR in WARWICKSHIRE, 162.0-1660 Cambridge Studies in Early Modern British History

Cambridge Studies in Early Modern British History POLITICS, SOCIETY AND CIVIL WAR IN WARWICKSHIRE, 162.0-1660 Cambridge Studies in Early Modern British History Series editors ANTHONY FLETCHER Professor of History, University of Durham JOHN GUY Reader in British History, University of Bristol and JOHN MORRILL Lecturer in History, University of Cambridge, and Fellow and Tutor of Selwyn College This is a new series of monographs and studies covering many aspects of the history of the British Isles between the late fifteenth century and the early eighteenth century. It will include the work of established scholars and pioneering work by a new generation of scholars. It will include both reviews and revisions of major topics and books which open up new historical terrain or which reveal startling new perspectives on familiar subjects. It is envisaged that all the volumes will set detailed research into broader perspectives and the books are intended for the use of students as well as of their teachers. Titles in the series The Common Peace: Participation and the Criminal Law in Seventeenth-Century England CYNTHIA B. HERRUP Politics, Society and Civil War in Warwickshire, 1620—1660 ANN HUGHES London Crowds in the Reign of Charles II: Propaganda and Politics from the Restoration to the Exclusion Crisis TIM HARRIS Criticism and Compliment: The Politics of Literature in the Reign of Charles I KEVIN SHARPE Central Government and the Localities: Hampshire 1649-1689 ANDREW COLEBY POLITICS, SOCIETY AND CIVIL WAR IN WARWICKSHIRE, i620-1660 ANN HUGHES Lecturer in History, University of Manchester The right of the University of Cambridge to print and sell all manner of books was granted by Henry VIII in 1534. -

Law, Counsel, and Commonwealth: Languages of Power in the Early English Reformation

Law, Counsel, and Commonwealth: Languages of Power in the Early English Reformation Christine M. Knaack Doctor of Philosophy University of York History April 2015 2 Abstract This thesis examines how power was re-articulated in light of the royal supremacy during the early stages of the English Reformation. It argues that key words and concepts, particularly those involving law, counsel, and commonwealth, formed the basis of political participation during this period. These concepts were invoked with the aim of influencing the king or his ministers, of drawing attention to problems the kingdom faced, or of expressing a political ideal. This thesis demonstrates that these languages of power were present in a wide variety of contexts, appearing not only in official documents such as laws and royal proclamations, but also in manuscript texts, printed books, sermons, complaints, and other texts directed at king and counsellors alike. The prose dialogue and the medium of translation were employed in order to express political concerns. This thesis shows that political languages were available to a much wider range of participants than has been previously acknowledged. Part One focuses on the period c. 1528-36, investigating the role of languages of power during the period encompassing the Reformation Parliament. The legislation passed during this Parliament re-articulated notions of the realm’s social order, creating a body politic that encompassed temporal and spiritual members of the realm alike and positioning the king as the head of that body. Writers and theorists examined legal changes by invoking the commonwealth, describing the social hierarchy as an organic body politic, and using the theme of counsel to acknowledge the king’s imperial authority. -

Coventry in the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography

Coventry in the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography The Oxford Dictionary of National Biography is the national record of people who have shaped British history, worldwide, from the Romans to the 21st century. The Oxford DNB (ODNB) currently includes the life stories of over 60,000 men and women who died in or before 2017. Over 1,300 of those lives contain references to Coventry, whether of events, offices, institutions, people, places, or sources preserved there. Of these, over 160 men and women in ODNB were either born, baptized, educated, died, or buried there. Many more, of course, spent periods of their life in Coventry and left their mark on the city’s history and its built environment. This survey brings together over 300 lives in ODNB connected with Coventry, ranging over ten centuries, extracted using the advanced search ‘life event’ and ‘full text’ features on the online site (www.oxforddnb.com). The same search functions can be used to explore the biographical histories of other places in the Coventry region: Kenilworth produces references in 229 articles, including 44 key life events; Leamington, 235 and 95; and Nuneaton, 69 and 17, for example. Most public libraries across the UK subscribe to ODNB, which means that the complete dictionary can be accessed for free via a local library. Libraries also offer 'remote access' which makes it possible to log in at any time at home (or anywhere that has internet access). Elsewhere, the ODNB is available online in schools, colleges, universities, and other institutions worldwide. Early benefactors: Godgifu [Godiva] and Leofric The benefactors of Coventry before the Norman conquest, Godgifu [Godiva] (d. -

1925-1926 Baconiana No 68-71.Pdf

m ■ lilSl « / , . t ! i■ i J l Vol. XVIII. Third Series. Comprising March & Dec. 1925, April & Dec., 1926. BACONIAN A -A ^Periodical ^ttagazine 1 5 [ T ) ) l l 7 LONDON: > GAY & HANCOCK, Limited, \ 12 AND 13, HENRIETTA ST., STRAND, W .C. I927 ‘ ’ Therefore we shall make our judgment upon the things themselves as they give light one to another and, as we can, dig Truth out of the mine.”—Francis Bacon r '■ CONTENTS. MARCH, 1925. page. The 364th Anniversary Dinner 1 Who was Shakespeare ? 10 The Eternal Controversy about Shakespeare 15 Shakespeare’s ‘ 'Augmentations’'. 18 An Historical Sketch of Canonbury Tower. 26 Shakespeare—Bacon’s Happy Youthful Life 37 ' 'Notions are the Soul of Words’' 43 Cambridge University and Shakespeare 52 Reports of Meetings 55 Sir Thomas More Again .. 60 George Gascoigne 04 Book Notes, Notes, etc. 67 DECEMBER, 1925. Biographers of Bacon 73 Bacon the Expert on Religious Foundations S3 ‘ ‘Composita Solvantur’ ’ . 90 Notes on Anthony Bacon’s Passports of 1586 93 The Shadow of Bacon’s Mind 105 Who Wrote the “Shakespeare” play, Henry VIII ? 117 Shakespeare and the Inns of Court 127 Book Notices 133 Correspondence .. 134 Notes and Notices 140 APRIL, 1926. Introduction to the Tercentenary Number r45 Introduction by Sir John A. Cockburn M7 The “Manes Verulamiani’' (in Latin and English), with Notes 157 Bacon and Seats of Learning 203 Francis Bacon and Gray’s Inn 212 Bacon and the Drama 217 Bacon as a Poet 227 Bacon on Himself 230 Bacon’s Friends and Critics 237 Bacon in the Shadow 259 Bacon as a Cryptographer 267 Appendix 269 Pallas Athene 272 Book Notices, Notes, etc. -

The Northern Clergy and the Pilgrimage of Grace Keith Altazin Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected]

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2011 The northern clergy and the Pilgrimage of Grace Keith Altazin Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Altazin, Keith, "The northern clergy and the Pilgrimage of Grace" (2011). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 543. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/543 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. THE NORTHERN CLERGY AND THE PILGRIMAGE OF GRACE A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The Department of History by Keith Altazin B.S., Louisiana State University, 1978 M.A., Southeastern Louisiana University, 2003 August 2011 Acknowledgments The completion of this dissertation would have not been possible without the support, assistance, and encouragement of a number of people. First, I would like to thank the members of my doctoral committee who offered me great encouragement and support throughout the six years I spent in the graduate program. I would especially like thank Dr. Victor Stater for his support throughout my journey in the PhD program at LSU. From the moment I approached him with my ideas on the Pilgrimage of Grace, he has offered extremely helpful advice and constructive criticism. -

Much Ado About Nothing – Beatrice – Act IV, Scene I

Much Ado About Nothing – Beatrice – Act IV, Scene I BEATRICE Is he not approved in the height a villain, that hath slandered, scorned, dishonored my kinswoman? Oh, that I were a man! What, bear her in hand until they come to take hands and then, with public accusation, uncovered slander, unmitigated rancor—O God, that I were a man! I would eat his heart in the marketplace. Princes and counties! Surely, a princely testimony, a goodly count, Count Comfect, a sweet gallant, surely! Oh, that I were a man for his sake! Or that I had any friend would be a man for my sake! But manhood is melted into curtsies, valor into compliment, and men are only turned into tongue, and trim ones too. He is now as valiant as Hercules that only tells a lie and swears it. I cannot be a man with wishing, therefore I will die a woman with grieving. Summer 2020 Hamlet, Prince of Denmark – Hamlet – Act III, Scene I HAMLET To be, or not to be? That is the question— Whether ’tis nobler in the mind to suffer The slings and arrows of outrageous fortune, Or to take arms against a sea of troubles, And, by opposing, end them? To die, to sleep— No more—and by a sleep to say we end The heartache and the thousand natural shocks That flesh is heir to—’tis a consummation Devoutly to be wished! To die, to sleep. To sleep, perchance to dream—ay, there’s the rub, For in that sleep of death what dreams may come When we have shuffled off this mortal coil, Must give us pause. -

Shakespeare for Life

Hamlet By William Shakespeare This lesson was inspired by the Macmillan Readers adaption of William Shakespeare’s original playscript. The language has been adapted and graded to make it suitable for readers at Intermediate level. It also features extracts of key speeches from the original text along with explanatory notes, plus glossaries and exercises designed to reinforce understanding post reading. The book is available with CD, as an audio book and as an eBook. Find out more here. • Order print books • Buy eBooks shakespeare for life www.macmillanreaders.com/shakespeare ©2016 Macmillan Education Hamlet TEACHEr’s NOTES LESSON OVERVIEW Level: Intermediate Length: Approximately 40 minutes Language focus: Expressions from Shakespeare’s Hamlet Learning objectives: In this lesson students complete a series of tasks that will help them to build their vocabulary and speaking skills. Students will have the chance to: • Gain an overview of the story of Hamlet and its characters • Learn a series of expressions from the play still in use today • Discuss ghosts and the supernatural and build related vocabulary • Read, analyse and practise reciting a famous speech from the play ContentS • Activity 1: Shakespeare’s Language • Activity 2: Speak Shakespeare Additional Activities: • Themed Discussion • Vocabulary Task HAMLET: TEACHER’S NOTES HAMLET: TEACHER’S shakespeare for life www.macmillanreaders.com/shakespeare ©2016 Macmillan Education Hamlet OVERVIEW OF the PLAy Key themes: Mortality, madness, ghosts, the supernatural and revenge Key characters: • Hamlet: The tragic hero of the play. Hamlet is Prince of Denmark and the son of Queen Gertrude and the late King Hamlet. Bitter and cynical and full of hatred for his Uncle Claudius. -

Notes on the Bacon-Shakespeare Question

NOTES ON THE BACON-SHAKESPEARE QUESTION BY CHARLES ALLEN BOSTON AND NEW YORK HOUGHTON, MIFFLIN AND COMPANY ftiucrsi&c press, 1900 COPYRIGHT, 1900, BY CHARLES ALLEN ALL RIGHTS RESERVED GIFT PREFACE AN attempt is here made to throw some new light, at least for those who are Dot already Shakespearian scholars, upon the still vexed ques- tion of the authorship of the plays and poems which bear Shakespeare's name. In the first place, it has seemed to me that the Baconian ar- gument from the legal knowledge shown in the plays is of slight weight, but that heretofore it has not been adequately met. Accordingly I have en- deavored with some elaboration to make it plain that this legal knowledge was not extraordinary, or such as to imply that the author was educated as a lawyer, or even as a lawyer's clerk. In ad- dition to dealing with this rather technical phase of the general subject, I have sought from the plays themselves and from other sources to bring together materials which have a bearing upon the question of authorship, and some of which, though familiar enough of themselves, have not been sufficiently considered in this special aspect. The writer of the plays showed an intimate M758108 iv PREFACE familiarity with many things which it is believed would have been known to Shakespeare but not to Bacon and I have to collect the most '; soughtO important of these, to exhibit them in some de- tail, and to arrange them in order, so that their weight may be easily understood and appreci- ated.