Defamation and Malicious Falsehood

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

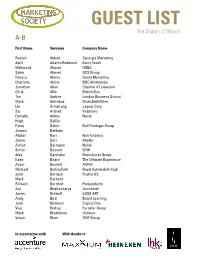

GUEST LIST the Shard | 12 March A-B

GUEST LIST The Shard | 12 March A-B First Name Surname Company Name Russell Abbott Synergis Marketing April Adams-Redmond Kerry Foods Mahmood Ahmed HSBC Salim Ahmed GCS Group Rebeca Alamo Quant Marketing Charlotte Aldiss BBC Worldwide Jonathan Allan Channel 4 Television Chris Allin British Gas Tim Ambler London Business School Mark Antrobus GlaxoSmithKline Ian Armstrong Jaguar Cars Saj Arshad Vodafone Danielle Atkins Nokia Hugh Baillie Patsy Baker Bell Pottinger Group Joanna Baldwin Alistair Barr Barr Gazetas Jayne Barr Abellio Adrian Barragan Nokia Simon Bassett EMR Alex Batchelor BrainJuicer Group Katie Beard The Ultimate Experience Adam Beckett AVIVA Michael Bedingfield Royal Automobile Club John Bernard Firefox OS Mark Bernard Richard Bernholt Periproducts Joy Bhattacharya Accenture James Bidwell CASS ART Andy Bird Brand Learning John Birkbeck Capital One Viya Bishay Eurostar Group Mark Bleathman Unilever Vivian Blom TMF Group In association with With thanks to GUEST LIST The Shard | 12 March B-C First Name Surname Company Name Chris Bowry Eurostar Group Emma Bradley BBC Nick Bradley City & Guilds Colin Bradshaw Rapp Russell Braterman Vodafone Francesca Brosan Omobono Lorna Brown John Lewis Lucas Brown Total Media Group Pamela Brown British Gas Rob Bruce Whyte & Mackay Kevin Bryant E.ON UK Richard Burdett Horse & Country TV Matt Burgess Unilever Hugh Burkitt The Marketing Society Ivor Burns Camelot UK Lotteries Joanna Burton Crescent Communications Amanda Campbell Capital Shopping Centres David Campbell World Brands Limited Dominic -

Curriculum Vitae

Tel: 07778 321122 [email protected] www.rogeredwards.tv A versatile freelance lighting cameraman and self-shooting PD with considerable experience across the whole spectrum of broadcast and corporate television. Based near Plymouth, on the Devon and Cornwall border in the south west of England. Reliable, easy going, enthusiastic and thorough. Very skilled in the creative use of lighting. Happy to self-shoot as a PD or take direction. Used to making quick decisions and adapting to events as they unfold. Owner of a Sony FS7 with Fujinon MK Cinema zoom lenses and a set of primes, slider, Ronin RS2 gimbal, dolly and mini jib. Covering Devon, Cornwall, Somerset & Dorset. Bases in the South West and mid Wales and happy to work throughout the UK and abroad. Just completed a new 20 part series of “Water Colour Challenge” with Twofour Productions for Channel 5. BROADCAST CREDITS: “Watercolour Challenge” - CH5 Returning series with Fern Britton as amateur artists paint scenes chosen for them by a local expert. “Extreme Cake Makers” – CH4 series 2, 3 & 4 Following a group of elite baking experts while they turn delicious cakes into works of art for special occasions. “My Life in a Zoo” – CBBC Documentary following the daily lives of Milo and Ella living at Dartmoor Zoological Park in Devon. “Splash!” – ITV 1 Celebrities learn to dive mentored by Tom Daley and compete in live show presented by Vernon Kay and Gabby Logan. “Timothy Spall - Somewhere at Sea” - BBC4 (series 1, 2 & 3) BAFTA nominated series following Timothy Spall and his wife as they sail around the coast of Britain in a Dutch Barge. -

The Edmonds Effect: Noel Is the Real Deal on Amazon.Co.Uk

The Edmonds Effect: Noel is the real deal on Amazon.co.uk May 26, 2006 May 26, 2006, London: It started when sales of an unknown book called The Cosmic Ordering Service soared after Noel Edmonds gave it his backing - and now according to Amazon.co.uk, he seems to be working his magic again with the Deal or No Deal boardgame. The game is available on pre-order at Amazon, where it is outselling other pre-order games by 10 to 1 and is set to be the online retailer's biggest selling board game this Christmas. With more than 3 months till release, the home version of Edmonds' popular TV programme Deal or No Deal has seen a 400% sales increase on Amazon.co.uk in the past 4 weeks. In April, a mention of The Cosmic Ordering Service by Edmonds in an interview caused the book to leap to the top of the Amazon.co.uk Hot 100 books chart. "We foolishly thought that was it after Noel's House Party and Mr Blobby...how wrong we were," says Paul Sanders, Amazon.co.uk Senior Toys Buyer. "The success of Deal or No Deal shows that everything he touches right now seems to be turning to gold. I wouldn't be surprised to see the game under a few Christmas trees this year." For further information please contact the Amazon.co.uk press office on 020 8636 9280. About Amazon.co.uk Amazon.co.uk opened its virtual doors in October 1998, and strives to be the world's most customer-centric company, where customers can find and discover anything they might want to buy online. -

Islamophobia Monitoring Month: December 2020

ORGANIZATION OF ISLAMIC COOPERATION Political Affairs Department Islamophobia Observatory Islamophobia Monitoring Month: December 2020 OIC Islamophobia Observatory Issue: December 2020 Islamophobia Status (DEC 20) Manifestation Positive Developments 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 0 Asia Australia Europe International North America Organizations Manifestations Per Type/Continent (DEC 20) 9 8 7 Count of Discrimination 6 Count of Verbal & Physical Assault 5 Count of Hate Speech Count of Online Hate 4 Count of Hijab Incidents 3 Count of Mosque Incidents 2 Count of Policy Related 1 0 Asia Australia Europe North America 1 MANIFESTATION (DEC 20) Count of Discrimination 20% Count of Policy Related 44% Count of Verbal & Physical Assault 10% Count of Hate Speech 3% Count of Online Hate Count of Mosque Count of Hijab 7% Incidents Incidents 13% 3% Count of Positive Development on Count of Positive POSITIVE DEVELOPMENT Inter-Faiths Development on (DEC 20) 6% Hijab 3% Count of Public Policy 27% Count of Counter- balances on Far- Rights 27% Count of Police Arrests 10% Count of Positive Count of Court Views on Islam Decisions and Trials 10% 17% 2 MANIFESTATIONS OF ISLAMOPHOBIA NORTH AMERICA IsP140001-USA: New FBI Hate Crimes Report Spurs U.S. Muslims, Jews to Press for NO HATE Act Passage — On November 16, the USA’s Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI), released its annual report on hate crime statistics for 2019. According to the Muslim-Jewish Advisory Council (MJAC), the report grossly underestimated the number of hate crimes, as participation by local law enforcement agencies in the FBI's hate crime data collection system was not mandatory. -

Aug – Julie Burchill

2004/August JULIE BURCHILL– Publishing News Julie Burchill. Where exactly do you start? Opinions differ wildly - she’s been described on the one hand as ‘the Queen of English journalism’, and also as ‘the hack from hell’ - but one thing is pretty constant, she is never, ever ignored. For last almost 30 years, from her punk days on the NME to her most recent move from the Guardian to the Times, she has delighted in outraging her detractors and surprising her fans. And now? Now she’s written a teenage novel. Burchill is no stranger to the world of publishing, having produced many books, including the definitive S&F novel Ambition, plus newspaper and magazine columns and works of non-fiction, so why a teen novel? “It doesn’t do me much credit – and I’m not putting myself down – but I didn’t think the world was exactly waiting for another adult novel from me,” replies Burchill. “I had a No. 1 novel in 1989 but since then it’s been pretty much downhill. Also, inside me there’s no angst and no problems, and I think to write a great adult novel, like Graham Greene or Zoe Heller, you have to have a bit of angst inside you and I’ve reached a place in my life where I’m very happy and contented.” When she thought about attempting a teenage novel, Burchill was, she admits, delighted when she found out they were half the size of adult novels, ergo she wouldn’t have to “bang on for so long” and she also says she’d realised she hadn’t properly grown up. -

Reach PLC Summary Response to the Digital Markets Taskforce Call for Evidence

Reach PLC summary response to the Digital Markets Taskforce call for evidence Introduction Reach PLC is the largest national and regional news publisher in the UK, with influential and iconic brands such as the Daily Mirror, Daily Express, Sunday People, Daily Record, Daily Star, OK! and market leading regional titles including the Manchester Evening News, Liverpool Echo, Birmingham Mail and Bristol Post. Our network of over 70 websites provides 24/7 coverage of news, sport and showbiz stories, with over one billion views every month. Last year we sold 620 million newspapers, and we over 41 million people every month visit our websites – more than any other newspaper publisher in the UK. Changes to the Reach business Earlier this month we announced changes to the structure of our organisation to protect our news titles. This included plans to reduce our workforce from its current level of 4,700 by around 550 roles, gearing our cost base to the new market conditions resulting from the pandemic. These plans are still in consultation but are likely to result in the loss of over 300 journalist roles within the Reach business across national, regional and local titles. Reach accepts that consumers will continue to shift to its digital products, and digital growth is central to our future strategy. However, our ability to monetise our leading audience is significantly impacted by the domination of the advertising market by the leading tech platforms. Moreover, as a publisher of scale with a presence across national, regional and local markets, we have an ability to adapt and achieve efficiencies in the new market conditions that smaller local publishers do not. -

FIPP Management Board As at 21 March 2019 Chairman Ralph Büchi

FIPP Management Board as at 21 March 2019 Chairman Ralph Büchi, Chief Operating Officer of the Ringier Group & CEO of Ringier Axel Springer Switzerland AG, Ringier Axel Springer Switzerland AG, Switzerland Treasurer Erwin Fidelis Reisch, President & CEO, Alfons W. Gentner Verlag GmbH & Co. KG, Germany President & CEO, James Hewes, President & CEO, FIPP - the network for global media, UK Directors Kaisa Ala-Laurila, CEO, A-lehdet Oy, Finland Srinivasan Balasubramanian, Managing Director, Ananda Vikatan Publishers Private Limited, India Natasha Christie-Miller, Divisional CEO, Ascential, Ascential, UK Enrique Micheli, Executive Director, Asociación Argentina de Editores de Revistas (AAER), Argentina Yolanda Ausín Castañeda, General Manager, Asociación de Revistas de Información (ARI), Spain Julia Raphaely, CEO, Associated Media Publishing, South Africa Jan Bayer, Member of the Executive Board & President News Media, Axel Springer SE, Germany Andrew Moultrie, Director of Consumer Products, Publishing and Web Properties, UK, BBC Studios Distribution Limited, UK Helen O'Donnell, Head of Development, TalentWorks, BBC Studios Distribution Limited, UK Alfred Heintze, COO, Burda International Holding GmbH, Germany Wu Shangzhi, President, China Periodicals Association (CPA), China Pierre Lamunière, President & Chairman, Edipresse Group, Switzerland Porfirio Sánchez Galindo, CEO, Editorial Televisa S.A. de C.V., Mexico Aaron Asadi, Chief Operations Officer, Future Publishing Ltd, UK Rolf Heinz, President & CEO Prisma Media, President G+J International -

Chapter 9 of the Civil Law (Wrongs) Act 2002 Which Was Introduced by the Civil Law (Wrongs) Amendment Act 2005 and Commenced on 23 February 2006

PROTECTING REPUTATION DEFAMATION PRACTICE, PROCEDURE AND PRECEDENTS THE MANUAL by Peter Breen Protecting Reputation Defamation Practice, Procedure and Precedents THE MANUAL © Peter Breen 2014 Peter Breen & Associates Solicitors 164/78 William Street East Sydney NSW 2011 Tel: 0419 985 145 Fax: (02) 9331 3122 Email: [email protected] www.defamationsolicitor.com.au Contents Section 1 Introduction ............................................................................................... 1 Section 2 Current developments and recent cases ................................................. 5 Section 3 Relevant legislation and jurisdiction ..................................................... 11 3.1 Uniform Australian defamation laws since 2006 ........................................ 11 3.2 New South Wales law [Defamation Act 2005] ........................................... 11 3.3 Victoria law [Defamation Act 2005] .......................................................... 13 3.4 Queensland law [Defamation Act 2005] ..................................................... 13 3.5 Western Australia law [Defamation Act 2005] .......................................... 13 3.6 South Australia law [Defamation Act 2005] .............................................. 14 3.7 Tasmania law [Defamation Act 2005] ........................................................ 14 3.8 Northern Territory law [Defamation Act 2006] .......................................... 15 3.9 Australian Capital Territory law [Civil Law (Wrongs) Act 2002] ............. 15 3.10 -

City Index Announces Kate Garraway and Clare Nasir As May’S Celebrity Trader

CITY INDEX ANNOUNCES KATE GARRAWAY AND CLARE NASIR AS MAY’S CELEBRITY TRADER. London, UK, 15th May, 2011 – City Index, a global leader in Spread Betting, Contracts for Difference (CFDs) and margined foreign exchange, are Day Breaking the markets with Morning GMTV Presenter Kate Garraway and Weather Girl Clare Nasir for April’s Celebrity Trader. Kate Garraway and Clare Nasir have been staples of daytime television for years, wowing the nation at GMTV before taking up their current roles at Daybreak. The pair are two of the hardest working presenters on TV, so just how did they find the time to be this month’s City Index celebrity traders? Was it trading teamwork, or forex feuding? Kate has been an enthusiastic trader, the start of the competition saw her dive straight off the deep end and short the FTSE after reading that the markets had begun the week with a bearish undertone that looked set to continue. Her strategy – ‘selling in strength’. Kate sold at £10 per point a, rather brave and aggressive approach, resulting however in her receiving a nearly instantaneous margin call from trusted City Index Trader Kishan Mandalia. This didn’t shake her confidence however, and she did eventually enjoy something of a rally on this trade. Over optimism was her down-fall here unfortunately though, as the UK 100 Index pushed up towards the 6000 mark, resulting in a disappointing loss as the trade crystallized £130 down. This turn in fortune for the FTSE 100 was a welcome bonus for Clare on the other-hand, as she placed the opposing trade, taking a long position on the index and successfully crystallizing a £61 profit. -

Daily Mirror – American Election (2016)

A Level Media Studies – Set Product Factsheet Daily Mirror – American Election (2016) Credit: Daily Mirror, Thursday Novemeber 10, 2016 1 A Level Media Studies – Set Product Factsheet Daily Mirror – American Election (2016) Component 1 Media Products, Industries and Audiences – Newspapers Focus Areas: Media language Representation Media industries Audiences Media contexts policies that drew criticism from both sides of the Product Context political spectrum, a record of racist and sexist • National mid market Tabloid Newspaper behaviour, and a lack of political experience. established in 1903 and aimed at a predominantly The contemporary audience could be assumed working class readership, it follows a to be familiar with the codes and conventions traditionally left wing political stance. of tabloid newspapers and the sensationalised • This edition was published on the 10th mode of address that these newspapers present. • November 2016 following the unprecedented FRONT PAGE: The use of American iconography • high profile American election campaign in the subverted image of the Statue of Liberty which was eventually won by Republican draws the reader’s attention to the front page of Donald Trump, a 70 year old billionaire the newspaper. Here the statue is seen to be weeping famous for appearing on reality TV into her hands which creates meaning for the show The Apprentice USA. audience and is intended to be read as connoting • The Daily Mirror demonstrated an despair. The background of the image contains dark unequivocally oppositional response to clouds which can be interpreted as foreshadowing the result and views Trump as ill suited future events. The Daily Mirror has juxtaposed to such a high position of power. -

Ashton Patriotic Sublime.5.Pdf (9.823Mb)

commercial spaces like theaters, and to performances spanning the gamut from the solemn, to the joyous. This diversity encompassed celebrations outside the expected calendar of national days. Patriotic sentiment was even a key feature of events celebrating the economic and commercial expansion of the new nation. The commemorative celebration for the laying of the foundation-stone of the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad, the “great national work which is intended and calculated to cement more strongly the union of the Eastern and the Western States,” took place on July 4, 1828.1 It beautifully illustrated the musical ties that bound different spaces together – in this case a parade route, a temporary outdoor civic space, and the permanent space of the Holliday Street Theatre. Organizers chose July Fourth for the event, wishing to signal civic pride and affective patriotism. Baltimore filled with visitors in the days before the celebration, so that on the morning of the Fourth the “immense throng of spectators…filled every window in Baltimore-street, and the pavement below….fifty thousand spectators, at least, must have been present.” The parade was massive and incorporated a great diversity of groups, including “bands of music, trades, and other bodies.” One focal point was a huge model, “completely rigged,” of a naval vessel, the “Union,” complete with uniformed sailors. Bands playing patriotic tunes were interspersed amongst the nationalist imagery on display: militia uniforms, banners emblazoned with patriotic verse, national flags, eagle figures, shields, and more. Charles Carrollton, one of the last surviving signers of the Declaration of Independence, gave the main public address at the site, accompanied by a march composed for the occasion, the “Carrollton March” (see Figure 2.4). -

Lisa Maxwell on Family, Health and Stardom

Heartwww.heartofengland.nhs.uk SoulSummer 2011 & Introducing our new Hospital directors Paw-ly patients’ puppy love Health profile - obesity and dieting Good Hope looking to the future Lisa Maxwell on family, health and stardom Advancing Happy Solihull Baby talk Healthcare Birthday community at the winners to You+ dentists NEC p3 p4 p11 p14 Birmingham Heartlands Hospital - Solihull Hospital - Good Hope Hospital - Birmingham Chest Clinic TRUST NEWS A little note from the membership team... Welcome to the summer would like to see something edition of the Heart of in a future edition or would England NHS Foundation like to feedback on this Trust (HEFT) membership edition, we would love to magazine. We hope you hear from you. Simply call enjoy reading about the membership team on the latest news and (0121) 424 1218 or email developments taking place Sandra White, membership within our Hospitals and our manager, at Sandra.white@ community services. If you heartofengland.nhs.uk Good Hope looking to the future… Membership teams up with The Trust’s membership has recently teamed up with the Midlands Co- operative Society to attend a member relations event. Following the successful The two organisations launch of Good Hope’s plan to build upon their new ward block building, shared values, working attention is now to be collaboratively to identify turned to the next set common challenges and of investment projects host joint membership planned for the Hospital. A&E will provide an events. Plans are in place for a improved environment Key issues for new and upgraded A&E for our patients and exploration include and for two new theatres help streamline patient looking at more ways and a day case unit to be flow, helping to improve to ensure members and built to replace two older pressures on the system service users have their theatres at the Hospital.