Chromatic Clashes in the Music of Tune-Yards

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Siriusxm to Broadcast Lollapalooza Live--Hear Performances by Arcade Fire, Blink-182, Muse, the Killers, Lorde, Cage the Elephant and More

NEWS RELEASE SiriusXM to Broadcast Lollapalooza Live--Hear Performances by Arcade Fire, blink-182, Muse, The Killers, Lorde, Cage The Elephant and more 8/3/2017 NEW YORK, Aug. 3, 2017 /PRNewswire/ -- SiriusXM announced today that it will broadcast performances and backstage interviews from Lollapalooza in Chicago, from Friday, August 4 through Sunday, August 6, on SiriusXM's Alt Nation channel. The broadcast will include interviews and live performances by Arcade Fire, blink-182, Muse, The Killers, Lorde, Cage The Elephant, Liam Gallagher, Foster The People, Vance Joy, alt-J, The Shins, George Ezra, The xx, Spoon, Tritonal, Gryffin, Slushii, Alison Wonderland and many more. "From headliners like Arcade Fire, blink-182, and The Killers to rising stars like Rag'n'Bone Man and Kaleo, SiriusXM is thrilled to bring live music from the stages of Lollapalooza to SiriusXM listeners across North America," said Steve Blatter, Senior Vice President and General Manager, Music Programming, SiriusXM. SiriusXM's Lollapalooza broadcast will air on Alt Nation, channel 36, beginning Friday, August 4 at 2:00 pm ET through Sunday, August 6. The broadcast will also be available through the SiriusXM App on smartphones and other connected devices, as well as online at siriusxm.com. Select performances will also air on other SiriusXM channels including The Spectrum, SiriusXMU and Electric Area. Additionally, SiriusXM's Shade 45 and Hip Hop Nation channels will air select performances including Migos, Big Sean, Run The Jewels, 21 Savage, Machine Gun Kelly and more starting Monday, August 7 through Sunday, August 13. SiriusXM recently announced that its 200+ channels – including SiriusXM's Alt Nation – are now also available for streaming to SiriusXM subscribers nationwide with Amazon Alexa. -

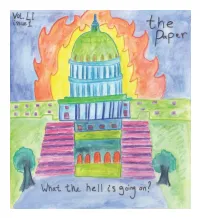

Vol LI Issue 1

page 2 the paper january 31, 2018 Marc Molinaro, pg. 3 Hygge, pg. 9 Oscars, pg. 15 F & L, pg. 21-22 Earwax, pg. 23 the paper “Favorite U.S. President Based on Looks” c/o Office of Student Involvement Editors-in-Chief Fordham University Colleen “Barack Obama” Burns Bronx, NY 10458 Claire “John Tyler” Nunez [email protected] Executive Editor http://fupaper.blog/ Michael Jack “Lyndon Baines Johnson” O’Brien News Editors the paper is Fordham’s journal of news, analysis, comment and review. Students from all Christian “Theodore Roosevelt” Decker years and disciplines get together biweekly to produce a printed version of the paper using Andrew “Rutherford B. Hayes” Millman Adobe InDesign and publish an online version using Wordpress. Photos are “borrowed” from Opinions Editors Internet sites and edited in Photoshop. Open meetings are held Tuesdays at 9:00 PM in McGin- Jack “Millard Fillmore” Archambault ley 2nd. Articles can be submitted via e-mail to [email protected]. Submissions from Hillary “Franklin Daddy Roosevelt” Bosch students are always considered and usually published. Our staff is more than willing to help new writers develop their own unique voices and figure out how to most effectively convey their Arts Editors thoughts and ideas. We do not assign topics to our writers either. The process is as follows: Meredith “Spiro Agnew” McLaughlin have an idea for an article, send us an e-mail or come to our meetings to pitch your idea, write Annie “Dead White Guy” Muscat the article, work on edits with us, and then get published! We are happy to work with anyone Earwax Editor who is interested, so if you have any questions, comments or concerns please shoot us an e- Marty “Andrew Jackson” Gatto mail or come to our next meeting. -

Verirrte Stutzer

Kultur Auch ohne die gängigen Rockerunifor- Ezra Koenig, der wie seine drei Partner POP men haben sie zusammen mit ihren beiden 23 ist, aber auch problemlos als 16-Jähriger Kollegen Rostam Batmanglij und Chris durchginge, setzt sich sehr aufrecht hin, Verirrte Stutzer Baio ein unlängst veröffentlichtes Debüt- wenn er nach Simon gefragt wird, und sagt album eingespielt, das als eines der aufre- verdächtig behutsam und etwas zu freund- Die Jungs von der New gendsten Ereignisse dieser Saison gilt. lich, dass alle in der Band dieses „sehr, sehr Im Internet versetzen sie seit Monaten respektieren“ würden, dass es aber ein Yorker Band Vampire Weekend die Welt der Musikblogs in Aufruhr, und in nervtötender Reflex sei, wenn alle Welt an widersprechen allen den einschlägigen Feuilletons amerikani- Paul Simon denke, sobald Nichtafrikaner gängigen Rock’n’Roll-Klischees. scher und englischer Zeitungen zeigen sich sich an afrikanischer Musik versuchten. die Experten angetan. Bereits im vergange- „Wir haben einfach den Zauber der afri- zra Koenig und Christopher Tomson, nen Sommer feierte ein Autor der „New kanischen Musik entdeckt und beschlos- die in einer fensterlosen Rumpelkam- York Times“ die erste Single des Quartetts sen, das mit unseren eigenen Ideen zu Emer ihrer Plattenfirma sitzen, trinken als „eines der beeindruckendsten Debüts kreuzen“, entgegnet er leicht entnervt. Ab- Mineralwasser ohne Kohlensäure und Cola des Jahres“. gesehen davon scheinen sich dieser Tage ohne Zucker und sehen eher nicht so aus, „Wir staunen nur, dass die Hallen, in de- immer mehr nachgewachsene Rockabenteu- wie man sich junge, gefeierte Rockmusiker nen wir spielen, immer größer und voller rer von sogenannter Weltmusik inspirie- aus New York vorstellt. -

Television Academy Awards

2021 Primetime Emmy® Awards Ballot Outstanding Music Composition For A Series (Original Dramatic Score) The Alienist: Angel Of Darkness Belly Of The Beast After the horrific murder of a Lying-In Hospital employee, the team are now hot on the heels of the murderer. Sara enlists the help of Joanna to tail their prime suspect. Sara, Kreizler and Moore try and put the pieces together. Bobby Krlic, Composer All Creatures Great And Small (MASTERPIECE) Episode 1 James Herriot interviews for a job with harried Yorkshire veterinarian Siegfried Farnon. His first day is full of surprises. Alexandra Harwood, Composer American Dad! 300 It’s the 300th episode of American Dad! The Smiths reminisce about the funniest thing that has ever happened to them in order to complete the application for a TV gameshow. Walter Murphy, Composer American Dad! The Last Ride Of The Dodge City Rambler The Smiths take the Dodge City Rambler train to visit Francine’s Aunt Karen in Dodge City, Kansas. Joel McNeely, Composer American Gods Conscience Of The King Despite his past following him to Lakeside, Shadow makes himself at home and builds relationships with the town’s residents. Laura and Salim continue to hunt for Wednesday, who attempts one final gambit to win over Demeter. Andrew Lockington, Composer Archer Best Friends Archer is head over heels for his new valet, Aleister. Will Archer do Aleister’s recommended rehabilitation exercises or just eat himself to death? JG Thirwell, Composer Away Go As the mission launches, Emma finds her mettle as commander tested by an onboard accident, a divided crew and a family emergency back on Earth. -

Jim Lambie Education Solo Exhibitions & Projects

FUNCTIONAL OBJECTS BY CONTEMPORARY ARTISTS ! ! ! ! !JIM LAMBIE Born in Glasgow, Scotland, 1964 !Lives and works in Glasgow ! !EDUCATION !1980 Glasgow School of Art, BA (Hons) Fine Art ! !SOLO EXHIBITIONS & PROJECTS 2015 Anton Kern Gallery, New York, NY (forthcoming) Zero Concerto, Roslyn Oxley9 Gallery, Sydney, Australia Sun Rise, Sun Ra, Sun Set, Rat Hole Gallery, Tokyo, Japan 2014 Answer Machine, Sadie Coles HQ, London, UK The Fruitmarket Gallery, Edinburgh, Scotland 2013 The Flowers of Romance, Pearl Lam Galleries, Hong Kong! 2012 Shaved Ice, The Modern Institute, Glasgow, Scotland Metal Box, Gerhardsen Gerner, Berlin, Germany you drunken me – Jim Lambie in collaboration with Richard Hell, Arch Six, Glasgow, Scotland Everything Louder Than Everything Else, Franco Noero Gallery, Torino, Italy 2011 Spiritualized, Anton Kern Gallery, New York, NY Beach Boy, Pier Art Centre, Orkney, Scotland Goss-Michael Foundation, Dallas, TX 2010 Boyzilian, Galerie Patrick Seguin, Paris, France Jupiter Artland, Edinburgh, Scotland Metal Urbain, The Modern Institute, Glasgow, Scotland! 2009 Atelier Hermes, Seoul, South Korea ! Jim Lambie: Selected works 1996- 2006, Charles Riva Collection, Brussels, Belgium Television, Sadie Coles HQ, London, UK 2008 RSVP: Jim Lambie, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, MA ! Festival Secret Afair, Inverleith House, Ediburgh, Scotland Forever Changes, Glasgow Museum of Modern Art, Glasgow, Scotland Rowche Rumble, c/o Atle Gerhardsen, Berlin, Germany Eight Miles High, ACCA, Melbourne, Australia Unknown Pleasures, Hara Museum of -

Concerts from the Library of Congress 2012-2013

Concerts from the Library of Congress 2012-2013 LIBRARY LATE ACME & yMusic Friday, November 30, 2012 9:30 in the evening sprenger theater Atlas performing arts center The McKim Fund in the Library of Congress was created in 1970 through a bequest of Mrs. W. Duncan McKim, concert violinist, who won international prominence under her maiden name, Leonora Jackson; the fund supports the commissioning and performance of chamber music for violin and piano. Please request ASL and ADA accommodations five days in advance of the concert at 202-707-6362 or [email protected]. Latecomers will be seated at a time determined by the artists for each concert. Children must be at least seven years old for admittance to the concerts. Other events are open to all ages. Please take note: UNAUTHORIZED USE OF PHOTOGRAPHIC AND SOUND RECORDING EQUIPMENT IS STRICTLY PROHIBITED. PATRONS ARE REQUESTED TO TURN OFF THEIR CELLULAR PHONES, ALARM WATCHES, OR OTHER NOISE-MAKING DEVICES THAT WOULD DISRUPT THE PERFORMANCE. Reserved tickets not claimed by five minutes before the beginning of the event will be distributed to stand-by patrons. Please recycle your programs at the conclusion of the concert. THE LIBRARY OF CONGRESS Atlas Performing Arts Center FRIDAY, NOVEMBER 30, 2012, at 9:30 p.m. THE mckim Fund In the Library of Congress American Contemporary Music Ensemble Rob Moose and Caleb Burhans, violin Nadia Sirota, viola Clarice Jensen, cello Timothy Andres, piano CAROLINE ADELAIDE SHAW Limestone and Felt, for viola and cello DON BYRON Spin, for violin and piano (McKim Fund Commission) JOHN CAGE (1912-1992) String Quartet in Four Parts (1950) Quietly Flowing Along Slowly Rocking Nearly Stationary Quodlibet MICK BARR ACMED, for violin, viola and cello Intermission *Meet the Artists* yMusic Alex Sopp, flutes Hideaki Aomori, clarinets C.J. -

Right Arm Resource Update

RIGHT ARM RESOURCE UPDATE JESSE BARNETT [email protected] (508) 238-5654 www.rightarmresource.com www.facebook.com/rightarmresource 12/10/2014 Counting Crows “Earthquake Driver” The second single from Somewhere Under Wonderland, available on PlayMPE and going for adds now! First week: KINK, WCOO, WEZZ, WEXT, KROK, WVOD, KOHO and KMTN Already on WNCS, WWCT, KCSN, KPND, WJCU, KBAC, KFMU, KMMS, KOZT, KSPN, KTAO, KYSL, WEHM, WFIV, WMWV, KCLC, KNBA, WAPS, WBJB, WMVY, WNRN, WYEP... FMQB Tracks Debut 44* on add week! Still on tour: 12/10 Louisville, 12/12 Indianapolis, 12/13 Madison, 12/16 Davenport IA Just added to the lineup for 2015’s Isle Of Wight Festival! Check out the lyric video on our site now Mark Ronson feat. Bruno Mars “Uptown Funk” The killer first single from the new Mark Ronson album Uptown Special, in stores January 27 Over 20 million views for the official video in just three weeks, fantastic performance on SNL Huge adds this week from WFUV, WXPN, WWNU, WRSI, WBJB, WJCU, WMWV, WCBE, WOCM and more Already on WXRV, KRVB, WZEW, KCMP, WFPK, WYMS, WNKU, KOHO and WCNR “Too good of a tune to just hand to CHR” - Jim McGuinn/KCMP “Stations like ours should be taking chances on songs like this” - John McGue/WNKU All Is Bright - Amazon Prime holiday playlist A brand new 43 song collection, available for your holiday programming now via PlayMPE download Features new holiday songs from Liz Phair, Anna Nalick, Ruby The Rabbitfoot, Blondfire and more along with brand new recordings of classics from Beth Orton, Lucinda Williams, Yoko Ono & The Flaming Lips, No Sinner, Brandi Carlile, Heartless Bastards, Houndmouth, Jessie Baylin, PHOX, Ruthie Foster and more Available for streaming for Amazon Prime members and individual track purchases through Amazon Music Bleachers “Rollercoaster” Foo Fighters “Something From Nothing” The second single from Strange Desire, featuring Jack Antonoff of fun. -

High Concept Music for Low Concept Minds

High concept music for low concept minds Music | Bittles’ Magazine: The music column from the end of the world: August/September New albums reviewed Part 1 Music doesn’t challenge anymore! It doesn’t ask questions, or stimulate. Institutions like the X-Factor, Spotify, EDM and landfill pop chameleons are dominating an important area of culture by churning out identikit pop clones with nothing of substance to say. Opinion is not only frowned upon, it is taboo! By JOHN BITTLES This is why we need musicians like The Black Dog, people who make angry, bitter compositions, highlighting inequality and how fucked we really are. Their new album Neither/Neither is a sonically dense and thrilling listen, capturing the brutal erosion of individuality in an increasingly technological and state-controlled world. In doing so they have somehow created one of the most mesmerising and important albums of the year. Music isn’t just about challenging the system though. Great music comes in a wide variety of formats. Something proven all too well in the rest of the albums reviewed this month. For instance, we also have the experimental pop of Georgia, the hazy chill-out of Nils Frahm, the Vangelis-style urban futurism of Auscultation, the dense electronica of Mueller Roedelius, the deep house grooves of Seb Wildblood and lots, lots more. Somehow though, it seems only fitting to start with the chilling reflection on the modern day systems of state control that is the latest work by UK electronic veterans The Black Dog. Their new album has, seemingly, been created in an attempt to give the dispossessed and repressed the knowledge of who and what the enemy is so they may arm themselves and fight back. -

Chance the Rapper, the Killers, Muse, Arcade Fire, the Xx, Lorde, Blink-182, Dj Snake, and Justice to Headline Lollapalooza 2017

CHANCE THE RAPPER, THE KILLERS, MUSE, ARCADE FIRE, THE XX, LORDE, BLINK-182, DJ SNAKE, AND JUSTICE TO HEADLINE LOLLAPALOOZA 2017 1-DAY TICKETS ON SALE TODAY AT 10AM CT Lineup posters: www.dropbox.com/sh/ea49gtywp85acvq/AADIgwnMcDVj0ontkkli0cfOa?dl=0 (Chicago, IL - March 22, 2017) Lollapalooza returns with another powerhouse lineup led by headliners Chance The Rapper, The Killers, Muse, Arcade Fire, The xx, Lorde, blink-182, DJ Snake, and Justice, delivering a diverse roster of some of the most exciting artists in today’s music landscape. After a historic 25th Anniversary, the world-class festival will return with four full days of music and over 170 bands in Chicago’s crown jewel, Grant Park, August 3-6. View the full lineup and lineup-by-day here. 2017 delivers a hero’s homecoming for recent Grammy-winner Chance The Rapper, a coveted performance from rock hit machine and Lolla veterans The Killers, alongside triumphant appearances from Muse, headlining for the first time in six years, and Arcade Fire, returning to command the main stage for their third performance in the festival’s 13-year Chicago history. Lollapalooza also welcomes heavy hitters including alt-J, Cage The Elephant, The Head and The Heart, Ryan Adams, Liam Gallagher, Phantogram and Spoon, while continuing to deliver fans artist discovery performances with hot new acts including Rag’n’Bone Man, Maggie Mae, 6lack, Sampha and Jain. Hip hop’s hottest stars will also take the stage, including Wiz Khalifa, Run the Jewels, Big Sean, Rae Sremmurd, Migos, Lil Uzi Vert, Lil Yachty, 21 Savage, Joey Bada$$, Noname, Russ, Machine Gun Kelly and Amine, while dance fans revel in performances from Kaskade, Porter Robinson, Zeds Dead, Crystal Castles, and many more. -

Vampire Weekend Father of the Bride Album Download Zip Vampire Weekend Father of the Bride Album Download Zip

vampire weekend father of the bride album download zip Vampire weekend father of the bride album download zip. Completing the CAPTCHA proves you are a human and gives you temporary access to the web property. What can I do to prevent this in the future? If you are on a personal connection, like at home, you can run an anti-virus scan on your device to make sure it is not infected with malware. If you are at an office or shared network, you can ask the network administrator to run a scan across the network looking for misconfigured or infected devices. Another way to prevent getting this page in the future is to use Privacy Pass. You may need to download version 2.0 now from the Chrome Web Store. Cloudflare Ray ID: 66c47b924e9b15f0 • Your IP : 188.246.226.140 • Performance & security by Cloudflare. Vampire weekend father of the bride album download zip. Rating: 8/10 | Genres: Indie Rock, Indie Pop. Review: "Father of the Bride" contains a masterpiece scattered around its 18 songs, quite few of them under 2 minutes and also few over 4. This is a rich record filled with things to listen to. Its genius is that it sounds content, like a victorious rallying cry among the band's most eclectic and pleasing sound yet, but still it hides Koenig's uncertainty and desperation. It is almost self-deprecating in a way. Now a grown house-man of sorts, Koenig woke up from the numbness of marriage and realizes he "got married in a gold rush". -

100 Years: a Century of Song 1930S

100 Years: A Century of Song 1930s Page 42 | 100 Years: A Century of song 1930 A Little of What You Fancy Don’t Be Cruel Here Comes Emily Brown / (Does You Good) to a Vegetabuel Cheer Up and Smile Marie Lloyd Lesley Sarony Jack Payne A Mother’s Lament Don’t Dilly Dally on Here we are again!? Various the Way (My Old Man) Fred Wheeler Marie Lloyd After Your Kiss / I’d Like Hey Diddle Diddle to Find the Guy That Don’t Have Any More, Harry Champion Wrote the Stein Song Missus Moore I am Yours Jack Payne Lily Morris Bert Lown Orchestra Alexander’s Ragtime Band Down at the Old I Lift Up My Finger Irving Berlin Bull and Bush Lesley Sarony Florrie Ford Amy / Oh! What a Silly I’m In The Market For You Place to Kiss a Girl Everybody knows me Van Phillips Jack Hylton in my old brown hat Harry Champion I’m Learning a Lot From Another Little Drink You / Singing a Song George Robey Exactly Like You / to the Stars Blue Is the Night Any Old Iron Roy Fox Jack Payne Harry Champion I’m Twenty-one today Fancy You Falling for Me / Jack Pleasants Beside the Seaside, Body and Soul Beside the Sea Jack Hylton I’m William the Conqueror Mark Sheridan Harry Champion Forty-Seven Ginger- Beware of Love / Headed Sailors If You were the Only Give Me Back My Heart Lesley Sarony Girl in the World Jack Payne George Robey Georgia On My Mind Body & Soul Hoagy Carmichael It’s a Long Way Paul Whiteman to Tipperary Get Happy Florrie Ford Boiled Beef and Carrots Nat Shilkret Harry Champion Jack o’ Lanterns / Great Day / Without a Song Wind in the Willows Broadway Baby Dolls -

BAM and Barclays Center Present Contemporary Color, Conceived by David Byrne

BAM and Barclays Center present Contemporary Color, Conceived by David Byrne David Byrne, Nelly Furtado, How to Dress Well, Devonté Hynes, Kelis, Nico Muhly + Ira Glass, St. Vincent, tUnE-yArDs and ten color guard teams from North America all perform LIVE Contemporary Color marks BAM’s first production partnership with Barclays Center, a historic pairing of performing arts institution and major arena June 27 & 28 at Barclays Center for BAM 2015 Winter/Spring Season June 22 & 23 at Toronto’s Air Canada Centre for Luminato Festival Bloomberg Philanthropies is the 2014/2015 Season Sponsor BAM and Barclays Center Present Contemporary Color Conceived by David Byrne Barclays Center (620 Atlantic Ave) Jun 27 & 28 at 7:30PM Tickets start at $25 On sale Jan 28 to general public (Jan 21 to Friends of BAM) Brooklyn, NY/Jan 21, 2015— BAM and Barclays Center present Contemporary Color, a performance event created by music icon David Byrne, co-commissioned by BAM and Toronto’s Luminato Festival, and inspired by the high school phenomenon of color guard, known as “the sport of the arts.” Ten 20-40 person color guard teams from the US and Canada will perform at Brooklyn’s Barclays Center and Toronto’s Air Canada Centre, alongside an extraordinary array of musical talent performing live. Contemporary Color is the artistic culmination of Byrne’s interest in color guard as a piece of Americana and a competitive art form. When Byrne agreed to lend a composition to a high school performance team back in 2008, he knew little about the color guard phenomenon, which is wildly popular in high schools across the North American continent.