CHAPTER 4 BADGER (Meles Meles L.)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

978–1–137–49934–9 Copyrighted Material – 978–1–137–49934–9

Copyrighted material – 978–1–137–49934–9 © Steve Ely 2015 All rights reserved. No reproduction, copy or transmission of this publication may be made without written permission. No portion of this publication may be reproduced, copied or transmitted save with written permission or in accordance with the provisions of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988, or under the terms of any licence permitting limited copying issued by the Copyright Licensing Agency, Saffron House, 6–10 Kirby Street, London EC1N 8TS. Any person who does any unauthorized act in relation to this publication may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages. The author has asserted his right to be identified as the author of this work in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. First published 2015 by PALGRAVE MACMILLAN Palgrave Macmillan in the UK is an imprint of Macmillan Publishers Limited, registered in England, company number 785998, of Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire RG21 6XS. Palgrave Macmillan in the US is a division of St Martin’s Press LLC, 175 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10010. Palgrave Macmillan is the global academic imprint of the above companies and has companies and representatives throughout the world. Palgrave® and Macmillan® are registered trademarks in the United States, the United Kingdom, Europe and other countries. ISBN 978–1–137–49934–9 This book is printed on paper suitable for recycling and made from fully managed and sustained forest sources. Logging, pulping and manufacturing processes are expected to conform to the environmental regulations of the country of origin. A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. -

A Revised Global Conservation Assessment of the Javan Ferret Badger Melogale Orientalis

Wilianto & Wibisono SHORT COMMUNICATION A revised global conservation assessment of the Javan Ferret Badger Melogale orientalis Erwin WILIANTO1* & Hariyo T WIBISONO1, 2 Abstract. 1. Sumatran Tiger Conservation Forum In 2008, Javan Ferret Badger Melogale orientalis was categorised as Data Deficient by The IUCN (HarimauKita), Jl. Samiaji III No. 10, Red List of Threatened Species, indicating that there was too little relevant information to assess its Bantarjati, Bogor, 16153, West Java, conservation status. According to the 2008 assessment, its known distribution was restricted to parts Indonesia. of the islands of Java and Bali with no records from Central Java and few, if any, explicitly from the lowlands or far from natural forest. During 2004–2014, 17 opportunistic Javan Ferret Badger records were obtained from various habitats, from 100 to nearly 2000 m altitude. These included 2. four records in Central Java and the adjacent Yogyakarta Special Region, filling in a gap in the Fauna & Flora International – Indonesia species’ known range. West Java records included three locations below 500 m altitude. Several Programme, Komplek Margasatwa records were from around villages, up to 5–8 km from the closest natural forest, indicating that this Baru No 7A, Jl. Margasatwa Raya, species uses heavily human-altered areas. This evidence of a wider altitudinal and spatial Jakarta, 12450, Indonesia distribution, and use of highly human-modified habitats, allowed re-categorisation in 2016 on the IUCN Red List as Least Concern. Ringkasan. Correspondence: Erwin Wilianto Pada tahun 2008, biul selentek Melogale orientalis dikategorikan kedalam kelompok Data Defecient (Kekurangan Data) dalam The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species yang [email protected] mengindikasikan bahwa saat itu sangat sedikit informasi yang digunakan untuk menilai status konservasi jenis ini. -

Yorkshire GREEN Corridor and Preliminary Routeing and Siting Study

Yorkshire GREEN Project – Corridor and Preliminary Routeing and Siting Study Report Yorkshire GREEN Project Corridor and Preliminary Routeing and Siting Study (YG-NSC-00001) National Grid National Grid House Warwick Technology Park Gallows Hill Warwick CV34 6DA Final - March 2021 Yorkshire GREEN Project – Corridor and Preliminary Routeing and Siting Study Report Page intentionally blank Yorkshire GREEN Project – Corridor and Preliminary Routeing and Siting Study Report Document Control Document Properties Organisation AECOM Ltd Author Alison Williams Approved by Michael Williams Title Yorkshire GREEN Project – Corridor and Preliminary Routeing and Siting Study Report Document Reference YG-NSC-00001 Version History Date Version Status Description/Changes 02 March 2021 V8 Final version Yorkshire GREEN Project – Corridor and Preliminary Routeing and Siting Study Report Page intentionally blank Yorkshire GREEN Project – Corridor and Preliminary Routeing and Siting Study Report Table of Contents 1. INTRODUCTION 1 1.1 Overview and Purpose 1 1.2 Background and Need 3 1.3 Description of the Project 3 1.4 Structure of this Report 7 1.5 The Project Team 7 2. APPROACH TO ROUTEING AND SITING 8 2.1 Overview of National Grid’s Approach 8 2.2 Route and Site Selection Process 11 2.3 Overview of Stages of Development 11 3. THE STUDY AREA 16 3.1 Introduction 16 3.2 York North Study Area 16 3.3 Tadcaster Study Area 17 3.4 Monk Fryston Study Area 17 4. YORK NORTH OPTIONS APPRAISAL 19 4.1 Approach to Appraisal 19 4.2 CSEC Siting Area Identification 19 4.3 Substation Siting Area Identification 19 4.4 Overhead Line Routeing Identification 20 4.5 Combination Options 20 4.6 Screening of York North Options 24 4.7 Options Appraisal Summary of Remaining York North Options 28 4.8 The Holford Rules and Horlock Rules 76 4.9 York North Preferred Option 76 5. -

Records of Sunda Stink-Badger Mydaus Javanensis from Rajuk Forest, Malinau, North Kalimantan, Indonesia

Records of Sunda Stink-badger Mydaus javanensis from Rajuk Forest, Malinau, North Kalimantan, Indonesia RUSTAM1 and A. J. GIORDANO2 Abstract Several records of the little known Sunda Stink-badger Mydaus javanensis from North Kalimantan, Indonesia, on the island of Borneo were gathered during a pilot survey of local mammals. Recent records from Indonesian Borneo are few. Field observa- tions and records of hunted individuals suggest a locally abundant population. Keywords: Borneo, camera-trap, hunting, Mephitidae, sight records, Teledu Catatan Kehadiran Teledu Sigung Mydaus javanensis dari Hutan Rajuk, Malinau, Kalimantan Utara, Indonesia Abstrak Beberapa catatan kehadiran jenis yang masih sangat jarang diketahui, Teledu Sigung Mydaus javanensis dari Kalimantan Utara, Indonesia, di Pulau Kalimantan berhasil dikumpulkan selama survey pendahuluan mamalia secara lokal. Catatan terkini tentang jenis ini dari Pulau Kalimantan wilayah Indonesia sangat sedikit. Observasi lapangan dan catatan temuan dari para pemburu menunjukkan bahwa populasi jenis ini melimpah secara lokal. Sunda Stink-badger Mydaus javanensis is a small ground- dwelling Old World relative of skunks (Mephitidae) that ap- pears to be patchily distributed across the islands of Borneo, Java, Sumatra and the Natuna archipelago (Corbet & Hill 1992, Hwang & Larivière 2003, Meijaard 2003, Long et al. 2008). Al- though listed as Least Concern by The IUCN Red List of Threat- ened Species (Long et al. 2008), too little is known about its range and ecological requirements to be sure of its conserva- tion status. Samejima et al. (in prep.) mapped most of the ap- oldproximately or spatially 170 imprecise records tothat be theyuseful traced for the from model. Borneo Of those as part in- cluded,of a species most distribution hail from the model; island’s those northernmost excluded were part, either the Ma too- laysian state of Sabah. -

First Record of Hose's Civet Diplogale Hosei from Indonesia

First record of Hose’s Civet Diplogale hosei from Indonesia, and records of other carnivores in the Schwaner Mountains, Central Kalimantan, Indonesia Hiromitsu SAMEJIMA1 and Gono SEMIADI2 Abstract One of the least-recorded carnivores in Borneo, Hose’s Civet Diplogale hosei , was filmed twice in a logging concession, the Katingan–Seruyan Block of Sari Bumi Kusuma Corporation, in the Schwaner Mountains, upper Seruyan River catchment, Central Kalimantan. This, the first record of this species in Indonesia, is about 500 km southwest of its previously known distribution (northern Borneo: Sarawak, Sabah and Brunei). Filmed at 325The m a.s.l., IUCN these Red List records of Threatened are below Species the previously known altitudinal range (450–1,800Prionailurus m). This preliminary planiceps survey forPardofelis medium badia and large and Otter mammals, Civet Cynogalerunning 100bennettii camera-traps in 10 plots for one (Bandedyear, identified Civet Hemigalus in this concession derbyanus 17 carnivores, Arctictis including, binturong on Neofelis diardi, three Endangered Pardofe species- lis(Flat-headed marmorata Cat and Sun Bear Helarctos malayanus, Bay Cat . ) and six Vulnerable species , Binturong , Sunda Clouded Leopard , Marbled Cat Keywords Cynogale bennettii, as well, Pardofelis as Hose’s badia Civet), Prionailurus planiceps Catatan: PertamaBorneo, camera-trapping, mengenai Musang Gunung Diplogale hosei di Indonesia, serta, sustainable karnivora forest management lainnya di daerah Pegunungan Schwaner, Kalimantan Tengah Abstrak Diplogale hosei Salah satu jenis karnivora yang jarang dijumpai di Borneo, Musang Gunung, , telah terekam dua kali di daerah- konsesi hutan Blok Katingan–Seruyan- PT. Sari Bumi Kusuma, Pegunungan Schwaner, di sekitar hulu Sungai Seruya, Kalimantan Tengah. Ini merupakan catatan pertama spesies tersebut terdapat di Indonesia, sekitar 500 km dari batas sebaran yang diketa hui saat ini (Sarawak, Sabah, Brunei). -

Making the Leap Support Them

Summer | 2021 education Education education and think about what you within plenty of time. Also, can do to help emotionally do not forget to apply for a Making the leap support them. bus pass if needed. CHECKLIST ● It is important to establish ● Encourage and support he transition from School uniform; Shirts/ a sincere and open your child’s independence primary school to Polo shirts, trousers, relationship with your child’s and free thinking – listen shorts/skirts, jumpers, secondary school is T new school. Be honest to their opinions and freely ties, blazer, fl eece a major step in your child’s about your child’s needs/ engage in conversation with Coat life. Although many children requirements and inform them. Not only will they Hat, scarves and will feel accustomed to the secondary school’s reinforce and share their gloves the change within the fi rst SENCO or your child’s Keepthoughts fit over about whatsummer they Socks couple of weeks, the new current primary school if are learning in secondary Comfortable shoes school transition can be BBQ Season you have any concerns. If school, it will also help them PE Kit; t-shirt, shorts, extremely daunting. Even Crafts: Fun Making the leap you consider your child to to develop social skills and trainers , socks and the most confi dent of - Get the Kids Involved! be vulnerable, ensure thatFishbowl help to encourage a strong gym bag children sometimes can feel to high school you have frequent contact sense of self. Rucksack/large bag overwhelmed when starting with a key member of sta Lunchbox and bottle secondary school and it’s at the secondary school Wash-proof fabric normal for the whole family to who you can work closely markers feel slightly apprehensive when A few tips from with you to help aid your School Supplies adjusting to the new routine. -

Kim's Meadowfields, Easingwold Bear Display

STAY SAFE Saturday, 6th June, 2020 In Social Partnership Keep Your Digital No. 009 ISSN 1749-5962 with Easingwold District FREE Community Care Association Email: [email protected] Distance www.easingwoldadvertiser.com The Easingwold Advertiser & Weekly News, The Advertiser Office, Market Place, Easingwold, York YO61 3AB. For Sales & Distribution call Claire, Tel: 01347 821329 e-mail: [email protected] Kim’s Meadowfields, Easingwold Bear Display All Sizes of Skips Fast, Reliable Service Recycling Your Waste Licensed Tipping Facilities Wait and Load Service Reclaimed Building Materials Crushed Rubble www.moverleyskiphire.co.uk [email protected] Suppliers of: Heating Oil AGA Additives Boiler Additives Run Out of Fuel! Don’t Worry 20 Litre Drums of Heating Oil Heidi Smith contacted us via Available to Collect Facebook to tell us about her aunt’s HG5 0RB amazing feat during lockdown which was originally....continued on page 2. 01423 396789 www.yorkshireoils.co.uk MARK [email protected] FAIRWEATHER GROUNDWORKS LTD Driveways Concreting Paths & Patios Garden Alterations Drainage Foundations CUNDALL MANOR Mark Hopkins Est 1988 Demolition NORTH YORKSHIRE 7.5 Ton - 360˚ Digger / 1.6 Ton - Mini YORKSHIRE 360˚ Digger LANDSCAPES LTD 7 Ton - 180˚ Digger Dumpers from 1 Ton to 4 Ton PATIOS • DRIVES • KEY BLOCK PAVING ½ Ton Single Drum Vibrating Roller STONE & BRICK WALLING • SUNKEN GARDENS 3 Ton Twin Drum Vibrating Roller Cycling Plus One of THE TREE SURGEON • PONDS • TURFING TOUGHEST All commercial, Agricultural -

B I B L I O G R a P H Y

B I B L I O G R A P H Y Abbreviations are made according to the Council for British Archaeology’s Standard List of Abbreviated Titles of Current Series as at April 1991. Titles not covered in this list are abbreviated according to British Standard BS 4148:1985, with some minor exceptions. (––––), 1848. ‘Ancient crosses’, Ecclesiologist, n. ser., VIII, (––––), 1984. Review of Ryder 1982, Bull. C.B.A. Churches 220–39 Committee, XX, 15–16 (––––), 1854. Review of Wardell 1853, in ‘Historical and (––––), 1991. Historic Churches of West Yorkshire: Tong Church, miscellaneous reviews’, Gentleman’s Magazine, n. ser., XLII, West Yorkshire Archaeology Service leaflet (Wakefield) pt. 2, 44–6 (––––), 1865. ‘Archaeological Institute’, Builder, XXIII Adams, M., 1996. ‘Excavation of a pre-Conquest cemetery (15 July 1865), 502 at Addingham, West Yorkshire’, Medieval Archaeol., XL, (––––), 1867. ‘The Huddersfield Archaeological and 151–91 Topgraphical Association: Walton Cross’, Huddersfield Adcock, G. A., 1974. ‘A study of the types of interlace on Examiner, 14 September 1867, 6 Northumbrian sculpture’ (Unpublished M.Phil. thesis, (––––), 1871a. ‘Church-building news’, Builder, XXIX 2 vols., University of Durham) (28 October 1871), 852–3 Adcock, G. A., 2002. ‘Interlaced animal design in Bernician (––––), 1871b. ‘Report of the Council ... Feb. 7th, 1871’, in stone sculpture examined in the light of the design concepts Yorkshire Philosophical Society, Annual Report for in the Lindisfarne Gospels’ (Unpublished Ph.D. thesis, 3 vols., University of Durham) MDCCCLXX (York), 7–17 Addy, S. O., 1893. The Hall of Waltheof (London and Sheffield) (––––), 1871c. ‘Donations to the Museum’, in Yorkshire Aitkenhead, N., Barclay, W. -

The 2008 IUCN Red Listings of the World's Small Carnivores

The 2008 IUCN red listings of the world’s small carnivores Jan SCHIPPER¹*, Michael HOFFMANN¹, J. W. DUCKWORTH² and James CONROY³ Abstract The global conservation status of all the world’s mammals was assessed for the 2008 IUCN Red List. Of the 165 species of small carni- vores recognised during the process, two are Extinct (EX), one is Critically Endangered (CR), ten are Endangered (EN), 22 Vulnerable (VU), ten Near Threatened (NT), 15 Data Deficient (DD) and 105 Least Concern. Thus, 22% of the species for which a category was assigned other than DD were assessed as threatened (i.e. CR, EN or VU), as against 25% for mammals as a whole. Among otters, seven (58%) of the 12 species for which a category was assigned were identified as threatened. This reflects their attachment to rivers and other waterbodies, and heavy trade-driven hunting. The IUCN Red List species accounts are living documents to be updated annually, and further information to refine listings is welcome. Keywords: conservation status, Critically Endangered, Data Deficient, Endangered, Extinct, global threat listing, Least Concern, Near Threatened, Vulnerable Introduction dae (skunks and stink-badgers; 12), Mustelidae (weasels, martens, otters, badgers and allies; 59), Nandiniidae (African Palm-civet The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species is the most authorita- Nandinia binotata; one), Prionodontidae ([Asian] linsangs; two), tive resource currently available on the conservation status of the Procyonidae (raccoons, coatis and allies; 14), and Viverridae (civ- world’s biodiversity. In recent years, the overall number of spe- ets, including oyans [= ‘African linsangs’]; 33). The data reported cies included on the IUCN Red List has grown rapidly, largely as on herein are freely and publicly available via the 2008 IUCN Red a result of ongoing global assessment initiatives that have helped List website (www.iucnredlist.org/mammals). -

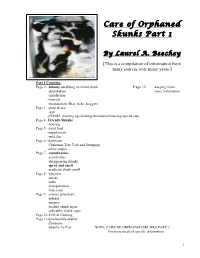

Care of Orphaned Skunks Part 1

Care of Orphaned Skunks Part 1 By Laurel A. Beechey [This is a compilation of information from many sources over many years.] Part 1 Contains: Page 2 - Infants-rehabbing an infant skunk P age 12 -keeping warm -dehydration -more information -rehydration -formula -examination: fleas, ticks, maggots Page 3 -poop & pee -age -CHART showing age/feeding/stimulation/housing/special care Page 4 Juvenile Skunks -housing Page 5 -solid food -supplements -wild diet Page 6 - bathroom -Christmas Tree Tails and Stomping -white stripes Page 7 -roundworms -sensitivities -disappearing skunks -spray and smell -eradicate skunk smell Page 8 -playtime -noises -nails -transportation -infections Page 9 -contact [physical] -release -surgery -healthy skunk signs -unhealthy skunk signs Page 10 -CPR & Choking Page 11-unreleasable skunks -Zoonoses -Skunks As Pets NOTE: CARE OF ORPHANED SKUNKS PART 2 For more medical specific information 1 INFANTS Keep Warm: Put the baby/babies in a box or cage with lots of rags and place a portion the box on a heating pad on low, leaving a portion unheated to allow the baby to move from the heat if necessary. Hot water in a jar, wrapped in a towel or a ‘hot water bottle’ can be used but the temperature must be monitored Find a wildlife rehabilitator in your area and get the animal to them as soon as possible. Can't locate one yet? Do the following and get the baby to a rehabber as soon as possible. Examine Let’s take a good look at it. Do you have some latex gloves? Write down what you find. Each skunk will have a different stripe & nose stripe to differentiate…note also if they are male or female…if unsure it is probably and female. -

Records of Small Carnivores from Bukit Barisan Selatan National Park, Southern Sumatra, Indonesia

Records of small carnivores from Bukit Barisan Selatan National Park, southern Sumatra, Indonesia Jennifer L. MCCARTHY1 and Todd K. FULLER2 Abstract Sumatra is home to numerous small carnivore species, yet there is little information on their status and ecology. A camera- trapping (1,636 camera-trap-nights) and live-trapping (1,265 trap nights) study of small cats (Felidae) in Bukit Barisan Selatan National Park recorded six small carnivore species: Masked Palm Civet Paguma larvata, Banded Civet Hemigalus derbyanus, Sumatran Hog Badger Arctonyx hoevenii, Yellow-throated Marten Martes flavigula, Banded Linsang Prionodon linsang and Sunda Stink-badger Mydaus javanensis effort, photo encounters for several of these species were few, despite their IUCN Red List status as Least Concern. This supports the need for current and comprehensive. An unidentified studies to otter assess (Lutrinae) the status was of also these recorded. species onEven Sumatra. given the relatively low camera-trap Keywords: Arctonyx hoevenii, camera-trapping, Hemigalus derbyanus, Martes flavigula, Mydaus javanensis, Paguma larvata, Pri- onodon linsang Catatan karnivora kecil dari Taman Nasional Bukit Barisan Selatan, Sumatera, Indonesia Abstrak Sumatera merupakan rumah bagi berbagai spesies karnivora berukuran kecil, namun informasi mengenai status dan ekologi spesies-spesies ini masih sedikit. Suatu studi mengenai kucing berukuran kecil (Felidae) menggunakan kamera penjebak dan perangkap hidup di Taman Nasional Bukit Barisan Selatan (1626 hari rekam) mencatat enam spesies karnivora kecil, yaitu: musang galing Paguma larvata, musang tekalong Hemigalus derbyanus, pulusan Arctonyx hoevenii, musang leher kuning Martes flavigula, linsang Prionodon linsang, dan sigung Mydaus javanensis. Tercatat juga satu spesies berang-berang yang tidak teriden- status mereka sebagai Least Concern. -

Directory of Establishments 2020/21- Index

CHILDREN AND YOUNG PEOPLE’S SERVICE DIRECTORY OF ESTABLISHMENTS 2020/21- INDEX Page No Primary Schools 2-35 Nursery School 36 Secondary Schools 37-41 Special Schools 42 Pupil Referral Service 43 Outdoor Education Centres 43 Adult Learning Service 44 Produced by: Children and Young People’s Service, County Hall, Northallerton, North Yorkshire, DL7 8AE Contact for Amendments or additional copies: – Marion Sadler tel: 01609 532234 e-mail: [email protected] For up to date information please visit the Gov.UK Get information about Schools page at https://get-information-schools.service.gov.uk/ 1 PRIMARY SCHOOLS Status Telephone County Council Ward School name and address Headteacher DfE No NC= nursery Email District Council area class Admiral Long Church of England Primary Mrs Elizabeth T: 01423 770185 3228 VC Lower Nidderdale & School, Burnt Yates, Harrogate, North Bedford E:admin@bishopthorntoncofe. Bishop Monkton Yorkshire, HG3 3EJ n-yorks.sch.uk Previously Bishop Thornton C of E Primary Harrogate Collaboration with Birstwith CE Primary School Ainderby Steeple Church of England Primary Mrs Fiona Sharp T: 01609 773519 3000 Academy Swale School, Station Lane, Morton On Swale, E: [email protected] Northallerton, North Yorkshire, Hambleton DL7 9QR Airy Hill Primary School, Waterstead Lane, Mrs Catherine T: 01947 602688 2190 Academy Whitby/Streonshalh Whitby, North Yorkshire, YO21 1PZ Mattewman E: [email protected] Scarborough NC Aiskew, Leeming Bar Church of England Mrs Bethany T: 01677 422403 3001 VC Swale Primary School, 2 Leeming Lane, Leeming Bar, Stanley E: admin@aiskewleemingbar. Northallerton, North Yorkshire, DL7 9AU n-yorks.sch.uk Hambleton Alanbrooke Community Primary School, Mrs Pippa Todd T: 01845 577474 2150 CS Sowerby Alanbrooke Barracks, Topcliffe, Thirsk, North E: admin@alanbrooke.