Mini-SITREP XLVIII

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

5 the Da Vinci Code Dan Brown

The Da Vinci Code By: Dan Brown ISBN: 0767905342 See detail of this book on Amazon.com Book served by AMAZON NOIR (www.amazon-noir.com) project by: PAOLO CIRIO paolocirio.net UBERMORGEN.COM ubermorgen.com ALESSANDRO LUDOVICO neural.it Page 1 CONTENTS Preface to the Paperback Edition vii Introduction xi PART I THE GREAT WAVES OF AMERICAN WEALTH ONE The Eighteenth and Nineteenth Centuries: From Privateersmen to Robber Barons TWO Serious Money: The Three Twentieth-Century Wealth Explosions THREE Millennial Plutographics: American Fortunes 3 47 and Misfortunes at the Turn of the Century zoART II THE ORIGINS, EVOLUTIONS, AND ENGINES OF WEALTH: Government, Global Leadership, and Technology FOUR The World Is Our Oyster: The Transformation of Leading World Economic Powers 171 FIVE Friends in High Places: Government, Political Influence, and Wealth 201 six Technology and the Uncertain Foundations of Anglo-American Wealth 249 0 ix Page 2 Page 3 CHAPTER ONE THE EIGHTEENTH AND NINETEENTH CENTURIES: FROM PRIVATEERSMEN TO ROBBER BARONS The people who own the country ought to govern it. John Jay, first chief justice of the United States, 1787 Many of our rich men have not been content with equal protection and equal benefits , but have besought us to make them richer by act of Congress. -Andrew Jackson, veto of Second Bank charter extension, 1832 Corruption dominates the ballot-box, the Legislatures, the Congress and touches even the ermine of the bench. The fruits of the toil of millions are boldly stolen to build up colossal fortunes for a few, unprecedented in the history of mankind; and the possessors of these, in turn, despise the Republic and endanger liberty. -

Financial Results Fiscal Year Ended March 31, 2014

Outline of Results Briefing by SQUARE ENIX HOLDINGS held on May 12, 2014 We would now like to begin the Financial Results Briefing Session of SQUARE ENIX HOLDINGS (the “Company”) for the fiscal year ended March 31, 2014 (the “FY2014/3”). Today’s presenters are: Yosuke Matsuda President and Representative Director and Kazuharu Watanabe 1 Chief Financial Officer. First, Matsuda will give a summary overview of the Company’s financial results for the FY2014/3 , and then explain the Company’s business strategy. Statements made in this document with respect to SQUARE ENIX HOLDINGS CO., LTD. and its consolidated subsidiaries' (together, “SQUARE ENIX GROUP") plans, estimates, strategies and beliefs are forward-looking statements about the future performance of SQUARE ENIX GROUP. These statements are based on management's assumptions and beliefs in light of information available to it at the time these material were drafted and, therefore, the reader should not place undue reliance on them. Also, the reader should not assume that statements made in this document will remain accurate or operative at a later time. A number of factors could cause actual results to be materially different from and worse than those discussed in forward-looking statements. Such factors include, but not limited to: 1. changes in economic conditions affecting our operations; 2. fluctuations in currency exchange rates, particularly with respect to the value of the Japanese yen, the U.S. dollar and the Euro; 3. SQUARE ENIX GROUP’s ability to continue to win acceptance of our products and services, which are offered in highly competitive markets characterized by the continuous introduction of new products and services, rapid developments in technology, and subjective and changing consumer preferences; 4. -

Jacob Ma-Weaver, CFA June 23, 2014 Last Price Diluted Shares Out

Long NetDragon Websoft (777 HK) Jacob Ma-Weaver, CFA June 23, 2014 Last Diluted Market Net Debt/ Enterprise Daily Insider Price Shares Out Cap (Cash) Value Liquidity Ownership HKD mm USD m USD m USD m 30d average USD m % 14.16 512 935 (693) 242 2.2 68 Dividend EV/Sales EV/EBITDA P/E P/E Ex- Book FCF Yield Yield 2014E 2014E 2014E Cash 2014E Value 2014E % x x x x HKD per share % 2.8 1.6 3.5 15.2 5.2 11.42 6.7 Souces: FactSet, company filings, proprietary estimates. NetDragon reports in CNY and trades in HKD. HKD and USD translations are provided for convenience at CNYHKD of 1.244 and USDHKD of 7.751. NetDragon is a pioneering Chinese Internet and education company masquerading as a game developer. Despite consistent cashflow from its gaming franchise and exciting growth prospects in education, mobile apps, and cloud computing, the company’s market valuation scarcely exceeds book value. Assuming fair market value for the company’s real estate holdings, investors are getting its cash cow game business and education ventures for free. NetDragon offers a compelling opportunity to invest alongside proven, trustworthy owner-operators in an absurdly underpriced portfolio of call options on large and fast-growing addressable markets. I estimate fair value today at HKD 27 per share, a 90% premium to the close on June 23. Although short-term volatility in the sector is high, NetDragon offers a highly asymmetric risk-return profile for long term-oriented investors. Fundamental downside should be limited by book value of HKD 11.42 per diluted share (HKD 10.50 of which is net cash), while realistic scenarios for NetDragon’s early stage businesses could result in 3-5x potential return on investment over the next few years. -

Sony Playstation 4

Sony PlayStation 4 Last Updated on September 24, 2021 Title Publisher Qty Box Man Comments Akiba's Trip 2 Acquire Aleste Collection M2 Aleste Collection: Game Gear Micro Include Edition M2 Assassin's Creed IV: Black Flag Ubisoft Assault Suit Leynos extreme Co.,Ltd. Battle Princess Madelyn 3goo K.K. Battlefield 4 Electronic Arts Biohazard 7: Resident Evil Capcom Biomutant THQ Nordic Blade Arcus from Shining EX Sega Blair Witch: Limited Edition Blaster Master Zero Trilogy: MetaFight Chronicle Inti Creates Boku no Hiro Academia: One's Justice Bandai Namco Entertainment BQM: Blockquest Maker: Complete Edition Wonderland Kazakiri Call of Duty: Ghosts Activision Capcom Belt Action Collection Capcom Capcom Belt Action Collection: Collector's Box Capcom Clannad Prototype Closed Nightmare Nippon Ichi Software Coffee Talk Chorus Worldwide Cyber Troopers: Virtual On x Toaru Majutsu no Index: Toaru Majutsu no Dennou Senki Sega Daedalus: The Awakening of Golden Jazz: Limited Edition Arc System Works Darius Burst: Chronicle Saviours CS Kadokawa Games / Taito Dark Souls III Bandai Namco Games Dark Souls III: The Fire Fades Edition From Software Dark Souls: Remastered Bandai Namco Entertainment Dead or Alive Xtreme 3: Fortune KoeiTecmo Detroit: Become Human: Premium Edition Sony Interactive Entertainment Devil May Cry 4: Special Edition Capcom Digimon World: Next Order Bandai Namco Entertainment Dragon Quest XI: Sugisarishi Toki O Motomete Square Enix Dragon's Crown Pro: Royal Package Atlus Earth Defense Force: Iron Rain D3 Publisher ESP RA.DE. ψ M2 ESP RA.DE. ψ: Limited Edition M2 Farming Simulator 17 Intergrow Fatal Twelve Prototype Fell Seal: Arbiter's Mark 1C Entertainment / DMM Games Fighting EX Layer Arc System Works Final Fantasy Reishiki HD: Suzaku Edition Square Enix Final Fantasy Reishiki HD Square Enix Game Tengoku CruisinMix Special Kadokawa Games Game Tengoku CruisinMix Special: Gokuraku Box Kadokawa Games Game Tengoku: Cruisin Mix : Gentai Box Kadokawa Games, Ltd., Degic.. -

2013 Annual Report

2013 Corporate Philosophy To spread happiness across the globe by providing unforgettable experiences This philosophy represents our company’s mission and the beliefs for which we stand. Each of our customers has his or her own definition of happiness. The Square Enix Group provides high-quality content, services, and products to help those customers create their own wonderful, unforgettable experiences, thereby allowing them to discover a happiness all their own. Management Guidelines These guidelines reflect the foundation of principles upon which our corporate philosophy stands, and serve as a standard of value for the Group and its members. We shall strive to achieve our corporate goals while closely considering the following: 1. Professionalism We shall exhibit a high degree of professionalism, ensuring optimum results in the workplace. We shall display initiative, make contin- ued efforts to further develop our expertise, and remain sincere and steadfast in the pursuit of our goals, while ultimately aspiring to forge a corporate culture disciplined by the pride we hold in our work. 2. Creativity and Innovation To attain and maintain new standards of value, there are questions we must ask ourselves: Is this creative? Is this innovative? Mediocre dedication can only result in mediocre achievements. Simply being content with the status quo can only lead to a collapse into oblivion. To prevent this from occurring and to avoid complacency, we must continue asking ourselves the aforemen- tioned questions. 3. Harmony Everything in the world interacts to form a massive system. Nothing can stand alone. Everything functions with an inevitable accord to reason. It is vital to gain a proper understanding of the constantly changing tides, and to take advantage of these variations instead of struggling against them. -

2016 Annual Report

2016 Corporate Philosophy To spread happiness across the globe by providing unforgettable experiences This philosophy represents our company’s mission and the beliefs for which we stand. Each of our customers has his or her own definition of happiness. The Square Enix Group provides high-quality content, services, and products to help those customers create their own wonderful, unforgettable experiences, thereby allowing them to discover a happiness all their own. Management Guidelines These guidelines reflect the foundation of principles upon which our corporate philosophy stands, and serve as a standard of value for the Group and its members. We shall strive to achieve our corporate goals while closely considering the following: 1. Professionalism We shall exhibit a high degree of professionalism, ensuring optimum results in the workplace. We shall display initiative, make continued efforts to further develop our expertise, and remain sincere and steadfast in the pursuit of our goals, while ultimately aspiring to forge a corporate culture disciplined by the pride we hold in our work. 2. Creativity and Innovation To attain and maintain new standards of value, there are questions we must ask ourselves: Is this creative? Is this innovative? Mediocre dedication can only result in mediocre achievements. Simply being content with the status quo can only lead to a collapse into oblivion. To prevent this from occurring and to avoid complacency, we must continue asking ourselves the aforementioned questions. 3. Harmony Everything in the world interacts to form a massive system. Nothing can stand alone. Everything functions with an inevitable accord to reason. It is vital to gain a proper understanding of the constantly changing tides, and to take advantage of these variations instead of struggling against them. -

2009 2010 2011 2012 by the End of 2012 There Were 136,000

Foreword There is no doubt that China has deservedly This report covers some basic information earned its reputation as a dynamic, large on demographics, politics and cultural and fast growing games market. It has context, as well as brief descriptions of the become an important constituent of the media, entertainment, telecoms and global games industry and what happens in internet sectors. It also contains short China is increasingly relevant to many profiles of the key local players in these executives outside of China. However, the sectors, including the leading local Chinese games market is in many respects AppStores, Search Engines and Social very different from other markets, in Networks. particular the main Western ones. To understand the Chinese games market it In the second part of this report, we helps to have a basic understanding of the describe the games market in more detail, broader cultural, economic and incorporating data from the recently technological context. released official China Game Publishers Association Publications Committee report, At Newzoo we have always promoted a our own research findings as well as some global perspective on the games market. In third party data. 2010, we started covering the Chinese market and completed our first large We also provide brief profiles of the key proprietary primary consumer survey in public and private game companies, some 2011. We since have developed extensive of the most popular client games and the knowledge of the Chinese market and its key game media companies that offer news main players, allowing us to assist our and information about games and the clients with access to, and interpretation of, games market. -

Netease Reveals Games Pipeline at Third Annual Game Enthusiasts' Day

Contact for Media and Investors: Juliet Yang NetEase, Inc. [email protected] Tel: (+86) 571-8985-3378 Brandi Piacente Investor Relations [email protected] Tel: (+1) 212-481-2050 NetEase Reveals Games Pipeline at Third Annual Game Enthusiasts' Day Beijing, May 22, 2017 – NetEase, Inc. (NASDAQ: NTES) (“NetEase” or the “Company”), one of China's leading internet and online game services providers, today announced that it celebrated its extensive portfolio of existing and upcoming mobile and PC-client games at the NetEase Third Annual “520 Game Enthusiasts’ Day.” Held on May 20, 2017 in Guangzhou, the event featured exciting new games that the Company expects to introduce in the coming quarters, and celebrated its flagship games that continue to reach new heights. During the event, NetEase showcased more than 30 titles including 13 never before released mobile games and two new PC titles that will add to its diverse portfolio. NetEase also announced the official launch of Qiyu Club, a player membership platform to provide exclusive rewards and privilege to all NetEase gamers. NetEase’s decades of leadership in online PC-client games, and more recently mobile games, have achieved tremendous success, with core IP continuing to gain favor with massive audiences. During the event, the Company announced plans to further extend its IP power, including the Fantasy Westward Journey, Westward Journey, Ghost and Tianxia franchises, with exciting themed carnival and competition events, as well as cartoons, TV shows and movies, to enrich the content and user engagement. NetEase also launched a brand new chapter for Onmyoji. With fully upgraded Augmented Reality (AR) gameplay and thrilling new content, players have flocked to the game in its initial days of the new chapter’s release to experience the exciting additions first hand. -

Press Release for Fiscal Year Ended March 31, 2013

SQUARE ENIX HOLDINGS CO., LTD. REPORTS FINANCIAL RESULTS FOR THE FISCAL YEAR ENDED MARCH 31, 2013 TOKYO, Japan – May 13, 2013-- SQUARE ENIX HOLDINGS CO., LTD. (the “Company”) today announced consolidated results for the fiscal year ended March 31, 2013. The Company is listed on the Tokyo Stock Exchange, First Section with the stock code “9684” and prepares its financial statements according to Japan GAAP. Key Figures (millions of yen, except percentages and per share data) Full year FY ended 3/13 FY ended 3/12 YoY change Net sales 147,981 127,896 +15.7% Operating income (6,081) 10,713 - Recurring income (4,378) 10,297 - Net income (loss) (13,714) 6,060 - Earnings (loss) (119.19 yen) 52.66 yen per share, basic - For additional information, please refer to the full-length Consolidated Financial Results document here: www.hd.square-enix.com/eng/13q4earnings.pdf or the Company’s IR website: www.square-enix.com/eng/ir Summary of consolidated financial results for the fiscal year ended March 31, 2013. In response to the latest environmental changes in the game industry, the Group has implemented various strategic initiatives such as a change in its development policy, organizational reforms, and redesign of some business models. As a result of such initiatives, the Group posts the extraordinary losses in addition to the recurring loss, which lead to net loss of 13,714 million yen for the fiscal year ended March 31, 2013,. In the Digital Entertainment segment, the Group’s operating income decreased significantly, primarily due to underperformance of major titles for consumer game consoles in North America and Europe. -

The Wonderful World of Arcade Simulators

WWW.OLDSCHOOLGAMERMAGAZINE.COM ISSUE #9 • MARCH 2019 FULL PAGE AD MARCH 2019 • ISSUE #9 SIMULATIONS PEOPLE AND PLACES The Sims Game Swappers of SoCal! 06 BY TODD FRIEDMAN 41 BY AARON BURGER SIMULATIONS PEOPLE AND PLACES Turn and Burn Frank Schwartraubner 08 BY PATRICK HICKEY JR. 42 BY MARC BURGER SIMULATIONS NEWS Fox’s Game: Lucasfilm, Mirage... Video Games Debut at Heritage Auctions 10 BY SHAUN JEX 43 BY BRETT WEISS SIMULATIONS REVIEWS Driver and Driver 2 New Books on Old School Gaming Topics 12 BY CONOR MCBRIEN 44 BY RYAN BURGER AND RIC PRYOR MICHAEL THOMASSON’S JUST 4 QIX COLLECTOR INFO Behind Enemy Lines Super Nintendo Pricer 14 BY MICHAEL THOMASSON 45 PRESENTED BY PRICECHARTING.COM BRETT’S OLD SCHOOL BARGAIN BIN NEWS Asteroids and Beamrider Great Retro Shops 16 BY BRETT WEISS 50 BY OLD SCHOOL GAMER REVIEWS Flip Grip: Bullet Heaven 20 BY ROB FARALDI REVIEWS Old Atari on Switch... 22 BY RYAN BURGER AND RIC PRYOR FEATURE Entering the Digitized Era - Part 1 24 BY WARREN DAVIS FEATURE Intruder Alert...Intruder Alert! 26 BY KEVIN BUTLER PRATT AT THE ARCADE Publisher Design Assistant Con Staff Leader Ryan Burger Marc Burger Paige Burger The Wonderful World of Arcade Simulators Editorial Board BY ADAM PRATT Editor Art Director 32 Brian Szarek Thor Thorvaldson Dan Loosen Doc Mack PEOPLE AND PLACES Business Manager Editorial Consultant Billy Mitchell Aaron Burger Dan Walsh Dan Kitchen: 2600 to Modern and Back Walter Day 35 BY OLD SCHOOL GAMER PEOPLE AND PLACES HOW TO REACH Postmaster – Send address changes to: OSG • 222 SE Main St • Grimes IA 50111 OLD SCHOOL GAMER: Dr. -

Anime/Games/J-Pop/J-Rock/Vocaloid

Anime/Games/J-Pop/J-Rock/Vocaloid Deutsch Alice Im Wunderland Opening Anne mit den roten Haaren Opening Attack On Titans So Ist Es Immer Beyblade Opening Biene Maja Opening Catpain Harlock Opening Card Captor Sakura Ending Chibi Maruko-Chan Opening Cutie Honey Opening Detektiv Conan OP 7 - Die Zeit steht still Detektiv Conan OP 8 - Ich Kann Nichts Dagegen Tun Detektiv Conan Opening 1 - 100 Jahre Geh'n Vorbei Detektiv Conan Opening 2 - Laufe Durch Die Zeit Detektiv Conan Opening 3 - Mit Aller Kraft Detektiv Conan Opening 4 - Mein Geheimnis Detektiv Conan Opening 5 - Die Liebe Kann Nicht Warten Die Tollen Fussball-Stars (Tsubasa) Opening Digimon Adventure Opening - Leb' Deinen Traum Digimon Adventure Opening - Leb' Deinen Traum (Instrumental) Digimon Adventure Wir Werden Siegen (Instrumental) Digimon Adventure 02 Opening - Ich Werde Da Sein Digimon Adventure 02 Opening - Ich Werde Da Sein (Insttrumental) Digimon Frontier Die Hyper Spirit Digitation (Instrumental) Digimon Frontier Opening - Wenn das Feuer In Dir Brennt Digimon Frontier Opening - Wenn das Feuer In Dir Brennt (Instrumental) (Lange Version) Digimon Frontier Wenn Du Willst (Instrumental) Digimon Tamers Eine Vision (Instrumental) Digimon Tamers Ending - Neuer Morgen Digimon Tamers Neuer Morgen (Instrumental) Digimon Tamers Opening - Der Grösste Träumer Digimon Tamers Opening - Der Grösste Träumer (Instrumental) Digimon Tamers Regenbogen Digimon Tamers Regenbogen (Instrumental) Digimon Tamers Sei Frei (Instrumental) Digimon Tamers Spiel Dein Spiel (Instrumental) DoReMi Ending Doremi -

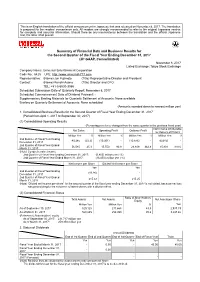

Summary of Financial Data and Business Results for the Second

This is an English translation of the official announcement in Japanese that was released on November 8, 2017. The translation is prepared for the readers’ convenience only. All readers are strongly recommended to refer to the original Japanese version for complete and accurate information. Should there be any inconsistency between the translation and the official Japanese text, the latter shall prevail. Summary of Financial Data and Business Results for the Second Quarter of the Fiscal Year Ending December 31, 2017 (JP GAAP, Consolidated) November 8, 2017 Listed Exchange: Tokyo Stock Exchange Company Name: Universal Entertainment Corporation Code No.: 6425 URL: http://www.universal-777.com Representative: (Name) Jun Fujimoto (Title) Representative Director and President Contact: (Name) Kenshi Asano (Title) Director and CFO TEL: +81-3-5530-3055 Scheduled Submission Date of Quarterly Report: November 8, 2017 Scheduled Commencement Date of Dividend Payment: - Supplementary Briefing Materials for Quarterly Settlement of Accounts: None available Briefing on Quarterly Settlement of Accounts: None scheduled (Amounts rounded down to nearest million yen) 1. Consolidated Business Results for the Second Quarter of Fiscal Year Ending December 31, 2017 (Period from April 1, 2017 to September 30, 2017) (1) Consolidated Operating Results (Percentages refer to changes from the same quarter in the previous fiscal year) Net Income Attributable Net Sales Operating Profit Ordinary Profit to Owners of Parent Million Yen % Million Yen % Million Yen % Million