Community Involvement in Public Art: an Overview

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Other Public Transportation

Other Public Transportation SCM Community Transportation Massachusetts Bay Transportation (Cost varies) Real-Time Authority (MBTA) Basic Information Fitchburg Commuter Rail at Porter Sq Door2Door transportation programs give senior Transit ($2 to $11/ride, passes available) citizens and persons with disabilities a way to be Customer Service/Travel Info: 617/222-3200 Goes to: North Station, Belmont Town Center, mobile. It offers free rides for medical dial-a-ride, Information NEXT BUS IN 2.5mins Phone: 800/392-6100 (TTY): 617/222-5146 Charles River Museum of Industry and Innovation grocery shopping, and Council on Aging meal sites. No more standing at (Waltham), Mass Audubon Drumlin Farm Wildlife Check website for eligibility requirements. a bus stop wondering Local bus fares: $1.50 with CharlieCard Sanctuary (Lincoln), Codman House (Lincoln), Rindge Ave scmtransportation.org when the next bus will $2.00 with CharlieTicket Concord Town Center Central Sq or cash on-board arrive. The T has more Connections: Red Line at Porter The Ride Arriving in: 2.5 min MBTA Subway fares: $2.00 with CharlieCard 7 min mbta.com/schedules_and_maps/rail/lines/?route=FITCHBRG The Ride provides door-to-door paratransit service for than 45 downloadable 16 min $2.50 with CharlieTicket Other Commuter Rail service is available from eligible customers who cannot use subways, buses, or real-time information Link passes (unlimited North and South stations to Singing Beach, Salem, trains due to a physical, mental, or cognitive disability. apps for smartphones, subway & local bus): $11.00 for 1 day $4 for ADA territory and $5 for premium territory. Gloucester, Providence, etc. -

Note: See the Tour Map Numbers That Correspond with the Following Text

Note: see the tour map numbers that correspond with the following text. 1. Cambridge Common The Cambridge Common is the City’s oldest public open space. In its present form, the Common consists of 8-1/2 acres of land, which is all that remains of the thousands of acres of common land that were granted to the original proprietors of Cambridge in 1630. During Colonial times, the Common was a place for military drill. The Common was originally landscaped as a park in 1830 and contains many commemorative monuments. 2. Brattle Street Cambridge’s most famous street, Brattle Street is known for its history and architecture. Most of the City’s remaining pre-Revolutionary era houses are located on Brattle Street, which is often called Tory Row because of the loyalist owners who built these old homes. The street boasts examples of the work of some of America’s best architects. Note the H. H. Richardson-designed Stoughton House (1883) at #90, the Vassal-Craigie-Longfellow House (1759) at #105, and the Hooper-Lee-Nichols House (1685) at #159. 3. Reservoir Street In 1856, the Cambridge Water Works constructed a steam pump on the shore of Fresh Pond from which the water was driven uphill through iron pipes to a reservoir on the Fayerweather estate. From Reservoir Hill, the water flowed by gravity to Old Cambridge. 4. Fresh Pond This natural landscape feature is a spring-fed lake, formed by a melting glacier. In the mid-eighteenth century, the shores were used as a wealthy resort destination. By the nineteenth century, the capability of Fresh Pond as a major ice harvesting supply was realized. -

Cambridge Public Art

Cambridge Arts Council CAMBRIDGE PUBLIC ART www.cambridgeartscouncil.org 01 02 Map 01 :: Alewife/Trolley Square (01) Clarendon Avenue Park: Juliet Kepes (02) Minuteman Bikeway: Carlos Dorrien (T) MBTA Station: Richard Fleischner, David Davidson, Joel Janowitz, Nancy Webb, Alejandro and Moira Sina Juliet Kepes Clarendon Avenue Park Title: Untitled Date: 1980 Materials: Bronze Dimensions: Ranging in size from 16" x 14" to 24" x21" Location: Intersection of Massachusetts Avenue and Clarendon Avenue The five bronze-birds, frozen in various stages of flight on a low brick wall next to the playground, are the creation of an acclaimed illustrator of children's books, Juliet Kepes. With a great affinity for animals, Kepes wrote 17 children's books with calligraphic drawings of birds, frogs and other creatures, three of which were designated in the top ten children's books of the year by the New York Times. Her Five Little Monkeys was selected as Caldicott Medal Honor Book and the Society of Illustrators awarded her a citation of merit for Frogs Merry in 1962. Juliet Kepes (1919-1979) resided in Cambridge for 53 years. She worked as a painter, sculptor, and graphic artist and collaborated with her husband, Gyorgy Kepes, on enamel murals for the Morse School and other public buildings. Commissioned by the Cambridge Arts Council. Funded by Vingo Trust . 2 © 2002 Cambridge Arts Council Map 01 :: Fact Sheet 01 Carlos Dorrien The Minuteman Bikeway Title: The Alewife Gateway Date: 1997 Materials: Granite Dimensions: 9' feet high each Location: On the north side of the Alewife MBTA station Carlos Dorrien's sculptural gateway consists of two granite monoliths, each with two polished surfaces and two sides naturally rusticated. -

Davis Square Statues” E-Mail to Executive Director of the Office of Housing and Community Development

The Statues of Davis Squares During the early 1980’s, the Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority decided to extend the Red Line from Harvard Square to Porter, Davis, and Alewife Square. Along with the extension, they decided to incorporate art into the stations through the “Arts on the Line” program. According to Steven Post, former Executive Director of the Office of Housing and Community Development (of Somerville), “it was important to make art part of the new station design and construction.” This can be seen not only at Davis Square, but at various other subway stations, such as the embedded bronze gloves scattered throughout Porter Square Station. In the beginning, the MBTA was afraid that people would be outraged that the money would be spent on art as part of the construction, but according to Pallas Lombardi, Executive Director of the Cambridge Arts Council, “as pieces got integrated into the system, people started to let us know what they thought, and it was overwhelming…People loved it…the feedback, the response to it, was incredible” (Lombardi). Originally, the statues, which are actually based on real people who lived around Davis Square, were all placed in the brick plaza in front of J.P. Licks and Store 24. However, around 1996, the City and the Somerville Arts Council decided to space out the statues in order to increase their influence around the square, thus placing them in their locations today. Also, have you ever noticed how the faces of the statues are darker than the rest of their bodies, as if they’re wearing some kind of Halloween masks? As stated by Steven Post, “the statues were meant to be ‘temporary’ in that they were not made of bronze. -

Subway Spaces As Public Places: Politics and Perceptions of Boston's T

Subway Spaces as Public Places: MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE Politics and Perceptions of Boston's T OF TEC HNO10LOGY by JUN 3 0 2011 Holly Bellocchio Durso Submitted to the Department of Urban Studies and Planning ARCHIVES in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degrees of Bachelor of Science in Planning and Master in City Planning at the MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY June 2011 @2011 Holly Bellocchio Durso. All Rights Reserved. The author hereby grants to MIT the permission to reproduce and to distribute publicly paper and electronic copies of the thesis document in whole or in part. Author C Department of Urban Studies and Planning May 19, 2011 Certified by Associate Professor Annette M. Kim Department of Urban Studies and Planning Thesis Supervisor Accepted by Professor Joseph Ferreira Chair, MCP Committee r Department of Urban Studies and Planning Subway Spaces as Public Places: Politics and Perceptions of Boston's T by Holly Bellocchio Durso Submitted to the Department of Urban Studies and Planning on May 19, 2011 in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degrees of Bachelor of Science in Planning and Master in City Planning ABSTRACT Subways play crucial transportation roles in our cities, but they also act as unique public spaces, distinguished by specific design characteristics, governed by powerful state-run institutions, and subject to intense public scrutiny and social debate. This thesis takes the case of the United States' oldest subway system-Boston's T-and explores how and why its spaces and regulations over their appropriate use have changed over time in response to public perceptions, political battles, and broader social forces. -

Public Art and Public Transportation

Public Art and Public Transportation Craig Amundsen, BKW, Inc. Building communities that rely on transit and walking will stewardship assumed by the community. Artistic expres• require greater attention to humanizing transit stations and sion, though, at times has been at odds with public opin• integrating them into their surrounding context. Public art ion. There can be an underlying fear of public art and the has a role in this process: it can help make transit stations inclusion of artists in the design of transit-related spaces. more than just places to wait. To build the image of transit Public art can be too provocative and seen as appealing to as an amenity in the community requires recognition of an elite audience rather than to regular people. Where has and sensitivity to the fact that the quality of the transpor• the inclusion of public art in transit projects been success• tation experience direcdy affects the quality of the lives of ful? What methods have been used to achieve positive re• transit users. The experience of travel by transit should be sults? How do constructive collaborations between artists, an attraction in itself. To build transit systems that are designers, and engineers happen? In what ways has the competitive with, if not better than, the experience of mov• inclusion of public art served to encourage pedestrian ac• ing by automobile requires attention to those things that cess to transit stations? These questions are addressed. make the public spaces serving transit successful. Spaces that serve to accommodate waiting, as well as sidewalks and paths to stations that connect surrounding activity ' I 1 he purpose of this paper is to examine success centers and land uses to transit, can be more interesting I factors in transit-related public art and architec- and made more secure by including public art in their de• A. -

Formulating an Arts Policy for BART: Findings and Recommendations

Formulating an Arts Policy for BART: Findings and Recommendations A Report Prepared by Regina Almaguer Fine Arts and Jeannene Przyblyski Art Consultants Submitted on June 3, 2015 Formulating an Arts Policy for BART: Findings and Recommendations Formulating an Arts Policy for BART was commissioned by the San Francisco Bay Area Rapid Transit District as a means of envisioning a transit system renewed by the creative vision of artists, where stations become artful places and plazas are activated with performances, gatherings, impromptu happenings and a variety of other cultural activities. It is has been both a challenge and a pleasure to undertake such an important task, and we are grateful for the opportunity to have collaborated with BART during this exciting period of inspired transition. Our work was informed by the guidance and support of the BART Board of Directors, and by members of BART management and staff. We would like to extend a special thank you to Grace Crunican, General Manager, Robert Powers, Assistant General Manager, Planning, Development & Construction, Val Menotti, Chief Planning and Development Officer, and most particularly to Abby Thorne-Lyman, Principal Planner, Strategic and Policy Planning, whose limitless energy and enthusiasm has kept us motivated throughout the process. We would also like to extend a heart-felt thank you the following agencies and art administrators for their generosity in sharing their experience, insight and advice with us: Bi-State Development Agency (David Allen), Charlotte Area Transit System (Pallas Lombardi), Chicago Transit Authority (Elizabeth Kelley), Greater Cleveland Regional Transit Authority (Maribeth Feke), Los Angeles County Metropolitan Transportation Authority (Maya Emsden), New Jersey Transit (Sheila D. -

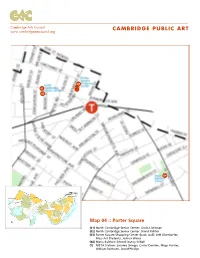

Cambridge Public

Cambridge Arts Council C A M B R I D G E P U B L I C A R T www.cambridgeartscouncil.org 03 01 02 04 Map 04 :: Porter Square (01) North Cambridge Senior Center: Linda Lichtman (02) North Cambridge Senior Center: David Fichter (03) Porter Square Shopping Center (back wall): Jeff Oberdorfer, Mass Art Students, Joshua Winer (04) Maria Baldwin School: Nancy O'Neil (T) MBTA Station: Susumu Shingu, Carlos Dorrien, Mags Harries, William Reimann, David Phillips Linda Lichtman North Cambridge Senior Center Title: Landscape Frieze in Glass Date: 1990 Materials: Etched stained glass, painted, and leaded Dimensions: 18" x 20' Location: 2050 Massachusetts Avenue These five panels of etched, stained and leaded glass run along the 20'-long glass window in the lobby of the Cambridge Senior Center. "I work with glass so that it will reflect nature and be alive to light, constantly changing like all things in nature," Lichtman says. "I tear away the surface of the glass with hydrofluoric acid or build up layers of paints, transparent enamels, and silver stain to increase richness and density." From this hazardous process emerges the most delicate of designs. Lichtman explains that each specific piece of glass etches differently. The result is the abstract imagery in "Landscape Frieze in Glass," which illumines the large window in the Cambridge Senior Center, as though the glass itself contained the light. Lichtman earned her BFA in painting from Massachusetts College of Art in 1974. She studied with a master glass artist Patrick Reyntiens at Burleighfiled House in England and apprenticed to other glass artists in the U.K., Canada and Germany before continuing studies at the Museum School in Boston. -

Davis Square Neighborhood Plan

DAVIS SQUARE NEIGHBORHOOD PLAN ADOPTION COPY July 19, 2019 The Mayor’s Office of Strategic Planning and Community Development is finalizing illustrations, correcting any clerical errors, cross checking references, and ensuring graphics provide clear and properly labeled information that is not substantive to the content of this plan. DAVIS SQUARE NEIGHBORHOOD PLAN PREPARED BY: TABLE OF CONTENTS: The Office of Strategic Planning & Community Development City of Somerville 93 Highland Avenue INTRODUCTION Somerville, MA 02143 Starts on Page 9 617-625-6600 [email protected] LIFE Starts on Page 33 WITH ASSISTANCE FROM: Gehl Studio Hurley Franks & Associates SPACE Principle Group Starts on Page 51 RCLCO Toole Design Group Urban Advantage BUILDINGS Utile Starts on Page 73 ADOPTED: IMPLEMENTATION Date TBD Starts on Page 101 What’s a Neighborhood Plan? A neighborhood plan takes Coming together as a community to think consideration of the long-term future of through challenges and solutions is just a neighborhood to identify challenges as important as publishing a document and opportunities, establish goals, and that records those efforts. The act of identify paths for implementation. It relies neighborhood planning allows members on extensive participation of residents, of the community to be proactive, businesses, and other stakeholders to contributing players in shaping the help translate the city-wide goals of forces of change. A plan that expresses a SomerVision to the neighborhood level. common vision for the future and lays out Somerville’s plans are action-oriented and clear objectives will allow stakeholders values-based, with an implementation to provide a timely and well-supported time frame up to 30 years. -

Ocm09499554-1989-01.Pdf (574.1Kb)

C-/I NEWSLETTER OF THE MASSACHUSETTS BAY Ti ATION AUTHORITY ADVISORY BOARD January 1989 Vol.6 No.1 " Southwest passage rates high'.W^ ,^ares in question Short headways on the Orange Line durina\wSQ-rv>i What is a fair fare? the Orange Line and bus hour. Riders-U§(^irra^^i?r9^ The question posed in the route #49 mask erratic a four car di/mg vOjJfe^^J^er- MBTA's brochure service according to the ience worse crowding than announcing hearings on a Advisory Board's Service during the six car string. proposed commuter rail fare Committee, which recently Alternating four and six car increase was answered by completed a field review of trains would seem to make 71 people during six hours of Southwest Corridor service. more sense. public testimony December The northern and southern The time between trains 12th and 13th. Additional portions of the Orange Line (headway) and the arrival riders sent written responses were observed for five days; times of trains were highly to the question. But the real bus route 49 (Dudley to erratic. Morning service on story was the hundreds of Downtown) which serves the both sides is scheduled at five riders who did not attend the Washington Street Corhdor minutes or less. Though the well publicized hearings, virtually mimicking the route observed average time leading to the conclusion that of the dismantled El was between trains was just over most are satisfied with observed for a similar period. four minutes, the variability service and are willing to pay Of the 107 a.m. -

Davis Square Neighborhood Plan

DAVIS SQUARE NEIGHBORHOOD PLAN PUBLIC REVIEW DRAFT APRIL 30, 2018 Over four years of your participation has led us to this public review draft of the Davis Square Neighborhood Plan. This is a live look in at the document as it is being developed. Text and imagery is still being finalized. We need your input to make sure nothing is missed. Please review this document and provide any feedback to [email protected] by June 1, 2018. DAVIS SQUARE NEIGHBORHOOD PLAN PREPARED BY: TABLE OF CONTENTS: The Office of Strategic Planning & Community Development City of Somerville 93 Highland Avenue INTRODUCTION Somerville, MA 02143 Pages TBD 617-625-6600 [email protected] LIFE Pages TBD WITH ASSISTANCE FROM: Gehl Studio Hurley Franks & Associates SPACE Principle Group Pages TBD RCLCO Toole Design Group Utile BUILDINGS Pages TBD ADOPTED: Date TBD P PLAN AREA OW DE RH The Davis Square O PACKARD AVE USE neighborhood generally B LVD includes from Packard and Cameron Avenue eastward to Willow Avenue and Russell Street and Powder House Boulevard and Kidder Avenue south-west to the Cambridge city line. This neighborhood CAMERON AVE KIDDER AVE plan primarily focuses on the the properties located within the core of Davis Square This area encompasses a primarily commercial district along Holland, Elm, Highland CAMBRIDGE LINE THE CORE and College near the MBTA’s Red Line. WILLOW AVE RUSSELL ST Davis Square Neighborhood Plan l 5 PLANNING HISTORY The Davis Square Action Plan On December 8, 1984 the MBTA’s Multiple new commercial office Northwest Extension of the Red Line buildings have brought jobs to the brought subway service to Davis neighborhood. -

Rapid Transit

Fares Lowell Line Haverhill Line Newburyport/ Rockport Line West Medford OAK GROVE Woodlawn 116 + + 111 WWONDERLANDONDERLAND Malden Center Revere Arlington Center Rapid Transit Arlington 77 Center Chelsea 117 Rapid Bus + Rapid Heights Revere PRICE PER TRIP Local Bus Bus + Bus Wellington Winter December 28, 2013 – March 21, 2014 Transit Transit Beach ALEWIFE 77 Bellingham Square Beachmont Davis Sullivan Sq CharlieCard $1.50 $1.50 $2.00 $2.00 Waverley Waltham Belmont Suffolk Downs Porter CharlieTicket $2.00 $2.00 $2.50 $4.50*** Community College Central BLUE LINE Square Orient Heights Cash-on-Board $2.00 $4.00 $2.50 $4.50*** Fitchburg Line ORANGE LINE Charlestown (E. Boston) Navy Yard 73 C h Wood Island Harvard LECHMERE a 116 r Student* $0.75 $0.75 $1.00 $1.00 71 73 le s t 117 Airport Science Park/ o 71 1 w 111 n RED LINE West End Senior/TAP** $0.75 $0.75 $1.00 $1.00 Watertown F Central e West Newton North Station r Square r Blue Line Newtonville 66 y Watertown Union Maverick UNLIMITED TRIP PASSES Yard Brighton Square Haymarket AIRPORT Kendall/MIT *BOWDOIN Newton Center (Allston) Long TERMINALS Wharf Corner 57 MIT 1-Day $11.00 $11.00 $11.00 $11.00 57 Government North Worcester Line Center Aquarium Charles/ Logan 7-Day $18.00 $18.00 $18.00 $18.00 1 MGH State Long Logan International Washington St BU Central Wharf Ferry Terminal Airport BOSTON B BU East South Monthly $48.00 $48.00 $70.00 $70.00 COLLEGE Park St Harvard Ave Rowes GREEN LINE Kenmore Wharf Sq ay Senior/TAP Monthly $28.00/month for unlimited travel on CLEVELAND Washington Coolidge Cnr Hynes Copley Arlington rade CtrW Quincy/Hull Ferry CIRCLE C Downtown T Local Bus and Rapid Transit RIVERSIDEWoodlandGREEN LINE GREEN LINE Crossing Green Line Courthouse Hingham Ferry D Yawkey World Trade Ctr Prudential SL4 SL1 R L Silver Line Way St.