Malcolm Burt Thesis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ACE's Scandinavian Sojourn

ACE’s Scandinavian Sojourn : A Southerner’s Perspective Story by: Richard Bostic, assisted by Ronny Cook When I went on the ACEspana trip back in 2009, it was by far one of the most amazing vacations I have ever experienced. In addition to getting to visit parks in a different culture than we see here, it is also a great opportunity to spend time with fellow enthusiasts and grow friendships while enjoying our common interests. When Scandinavia Sojourn was announced for the summer of 2011, I knew it was a trip I could not miss. Since the 2009 trip was my first trip to Europe I thought that there was no way the over- all experience could be better in Scandinavia. I was wrong. We landed in Helsinki, Finland around 1300 the day before we were required to be at the hotel to meet with the group. Helsinki is an interesting city and fairly new compared to many cities in Europe. Walking around the city you can see the Russian influence in the city’s architecture. In fact, many movies during the cold war would use Helsinki to shoot scenes that are supposed to be set in the Soviet Union. After making our way to the Crowne Plaza Hotel and getting a quick lunch at the hotel restaurant we decided to spend the remaining time that afternoon checking out some of the sites around our hotel. Some of these sites included the Temppeliaukio Church inside of a rock formation, the train station, Routatientori Square and National Theater, and a couple of the city’s art museums. -

Cedar Point Welcomes 2016 Golden Ticket Awards Ohio Park and Resort Host Event for Second Time SANDUSKY, Ohio — the First Chapter in Cedar and Beyond

2016 GOLDEN TICKET AWARDS V.I.P. BEST OF THE BEST! TM & ©2016 Amusement Today, Inc. September 2016 | Vol. 20 • Issue 6.2 www.goldenticketawards.com Cedar Point welcomes 2016 Golden Ticket Awards Ohio park and resort host event for second time SANDUSKY, Ohio — The first chapter in Cedar and beyond. Point's long history was written in 1870, when a bath- America’s top-rated park first hosted the Gold- ing beach opened on the peninsula at a time when en Ticket Awards in 2004, well before the ceremony such recreation was finding popularity with lake island continued to grow into the “Networking Event of the areas. Known for an abundance of cedar trees, the Year.” At that time, the awards were given out be- resort took its name from the region's natural beauty. low the final curve of the award-winning Millennium It would have been impossible for owners at the time Force. For 2016, the event offered a full weekend of to ever envision the world’s largest ride park. Today activities, including behind-the-scenes tours of the the resort has evolved into a funseeker’s dream with park, dinners and receptions, networking opportuni- a total of 71 rides, including one of the most impres- ties, ride time and a Jet Express excursion around sive lineups of roller coasters on the planet. the resort peninsula benefiting the National Roller Tourism became a booming business with the Coaster Museum and Archives. help of steamships and railroad lines. The original Amusement Today asked Vice President and bathhouse, beer garden and dance floor soon were General Manager Jason McClure what he was per- joined by hotels, picnic areas, baseball diamonds and sonally looking forward to most about hosting the a Grand Pavilion that hosted musical concerts and in- event. -

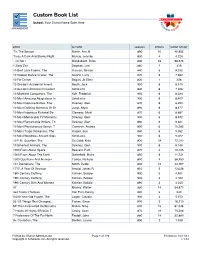

Custom Book List

Custom Book List School: Your District Name Goes Here MANAGEMENT BOOK AUTHOR LEXILE® POINTS WORD COUNT 'Tis The Season Martin, Ann M. 890 10 40,955 'Twas A Dark And Stormy Night Murray, Jennifer 830 4 4,224 ...Or Not? Mandabach, Brian 840 23 98,676 1 Zany Zoo Degman, Lori 860 1 415 10 Best Love Poems, The Hanson, Sharon 840 6 8,332 10 Coolest Dance Crazes, The Swartz, Larry 870 6 7,660 10 For Dinner Bogart, Jo Ellen 820 1 328 10 Greatest Accidental Inventi Booth, Jack 900 6 8,449 10 Greatest American President Scholastic 840 6 7,306 10 Mightiest Conquerors, The Koh, Frederick 900 6 8,034 10 Most Amazing Adaptations In Scholastic 900 6 8,409 10 Most Decisive Battles, The Downey, Glen 870 6 8,293 10 Most Defining Moments Of Th Junyk, Myra 890 6 8,477 10 Most Ingenious Fictional De Clemens, Micki 870 6 8,687 10 Most Memorable TV Moments, Downey, Glen 900 6 8,912 10 Most Remarkable Writers, Th Downey, Glen 860 6 9,321 10 Most Revolutionary Songs, T Cameron, Andrea 890 6 10,282 10 Most Tragic Romances, The Harper, Sue 860 6 9,052 10 Most Wondrous Ancient Sites Scholastic 900 6 9,022 10 P.M. Question, The De Goldi, Kate 830 18 72,103 10 Smartest Animals, The Downey, Glen 900 6 8,148 1000 Facts About Space Beasant, Pam 870 4 10,145 1000 Facts About The Earth Butterfield, Moira 850 6 11,721 1000 Questions And Answers Tames, Richard 890 9 38,950 101 Dalmatians, The Smith, Dodie 830 12 44,767 1777: A Year Of Decision Arnold, James R. -

List of Intamin Rides

List of Intamin rides This is a list of Intamin amusement rides. Some were supplied by, but not manufactured by, Intamin.[note 1] Contents List of roller coasters List of other attractions Drop towers Ferris wheels Flume rides Freefall rides Observation towers River rapids rides Shoot the chute rides Other rides See also Notes References External links List of roller coasters As of 2019, Intamin has built 163roller coasters around the world.[1] Name Model Park Country Opened Status Ref Family Granite Park United [2] Unknown Unknown Removed Formerly Lightning Bolt Coaster MGM Grand Adventures States 1993 to 2000 [3] Wilderness Run Children's United Cedar Point 1979 Operating [4] Formerly Jr. Gemini Coaster States Wooden United American Eagle Six Flags Great America 1981 Operating [5] Coaster States Montaña Rusa Children's Parque de la Ciudad 1982 Closed [6] Infantil Coaster Argentina Sitting Vertigorama Parque de la Ciudad 1983 Closed [7] Coaster Argentina Super Montaña Children's Parque de la Ciudad 1983 Removed [8] Rusa Infantil Coaster Argentina Bob Swiss Bob Efteling 1985 Operating [9] Netherlands Disaster Transport United Formerly Avalanche Swiss Bob Cedar Point 1985 Removed [10] States Run La Vibora 1986 Formerly Avalanche Six Flags Over Texas United [11] Swiss Bob 1984 to Operating Formerly Sarajevo Six Flags Magic Mountain States [12] 1985 Bobsleds Woodstock Express Formerly Runaway Reptar 1987 Children's California's Great America United [13] Formerly Green Smile 1984 to Operating Coaster Splashtown Water Park States [14] Mine -

Filming in Playland

FILMING IN PLAYLAND ver. 14-11-2019 RATE CARD PLAYLAND ICONIC LOCATION FILMING RENTAL RATES Playland is a local icon in British Columbia and has been featured in dozens of November-March $5,000.00 (daily) movie, TV and other film productions over the years. April-November $7,500.00 (daily) HOW THE RATES WORK: Playland is different than other locations on the PNE site because it is constantly All filming requires a minimum of 1: changing. Throughout the year, the park is either open and active, or busy with • PNE Playland Technician/Liaison the preparation for the opening and closing of each season. There are many • PNE Public Safety/Security elements to Playland which means filming can take up several footprints. Ask the Film Manager for This package is designed to help you decide on the size, budget and scope of Staffing and Venue Services Rate Card your shoot before a contract is drawn up. The daily rate is for access inside the park however use of any rides, games or booths is additional as outlined in this package. A 10% administration fee is applied to all charges and is additional to the fees and rates outlined in this package. Rides and attractions occasionally need repair or maintenance and may become unavailable unexpectedly. All filming in Playland requires a proposal in writing before filming is approved. Fiona Crossley • [email protected] • 604-252-3532 • • ver. 14-11-2019 RATE CARD WOODEN ROLLER COASTER FILMING RENTAL DAILY RATE Built in 1958, the Wooden Roller Coaster is Playland’s most historic and $1,875.00 spectacular attraction. -

Hershey Park: Sky Rush's Airtime Is the Name of the Game

Hershey Park: Sky Rush's airtime is the name of the game Author : If you're looking for a thrill, look no further than Skyrush at Hersheypark. The 2012 coaster from Intamin is one of the most extreme coasters I've been on. Not so much for the height or speed, but the insane amount of airtime you get. Regarding airtime, this is a top coaster for me. I'd put it in the same class as Diamondback at Kings Island. Skyrush really is a rush, and it's easily one of the best hyper coasters in North America. Of course, Skyrush is more than just a hyper coaster. It's also a wing coaster. While I didn't get the chance to ride on the two wing seats, it's got to be an awesome feeling, especially on a ride with so much airtime. The hope is next time I visit Hersheypark I'll take a ride on the wing. Related Post: Viper Is An Underrated Gem At Six Flags Great America As for the ride itself, Skyrush is a really good coaster. I've mentioned the airtime to death, but you really can't say it enough. With only a lap bar restraint, you'll feel the ejector airtime. The only issue I had with the restraints is that they come down hard on your legs. It's a harrowing feeling going down some of those airtime hills. It's said that second hill on Skyrush puts out -2 G's. That's quite an impressive feat, and you can tell when you're on the coaster. -

At August 2013 Web.Pdf

REGISTER NOW TO ATTEND 2013 GOLDEN TICKET AWARDS — PAGE 7 © TM Your Amusement Industry NEWS Leader! Vol. 17 • Issue 5 AUGUST 2013 Gold Striker marks a shiny new era for California’s Great America STORY: Dean Lamanna across the bow — the start of and fastest wooden coaster in [email protected] a new beginning,” said Raul Northern California. Deliv- SANTA CLARA, Calif. — Rehnborg, CGA’s vice presi- ering what Rehnborg calls a The steady stream of shrieks dent and general manager, of “world-class” combination of and post-ride buzz emanating the twisting wooden thriller nostalgia and smooth, state- from Gold Striker, the eighth rising from the park’s Celebra- of-the-art engineering along and newest roller coaster at tion Plaza. “Not only is the nearly 3,200 feet of tightly California’s Great America coaster exciting in and of itself, curving, heavily banked (up to (CGA), initially rattled the it really is a symbol of bigger 85 degrees), sometimes low-to- Billed as the tallest and fastest wooden roller coaster in nerves of some of the neigh- and better things to come.” the-ground track, the ride also Northern California, Gold Striker has drawn raves from park bors. But to the park’s opera- With a 103-foot-long first boasts an initial descent tunnel guests who have been waiting, and rooting, for the come- tors, the lack of silence is, well, plunge and speeds approach- of 174 feet — the longest ever back of California’s Great America. golden. ing 54 mph, Gold Striker is installed on a wooden coaster. -

Six Flags Partner in Two New Runaway Hits Six Flags Mexico and Six Flags Great America Debut New Coaster Experiences STORY: Tim Baldwin [email protected]

INSIDE: TM & ©2014 Amusement Today, Inc. Schlitterbahn KC opens record height slide — 15 & 16 September 2014 | Vol. 18 • Issue 6.1 www.amusementtoday.com Rocky Mountain and Six Flags partner in two new runaway hits Six Flags Mexico and Six Flags Great America debut new coaster experiences STORY: Tim Baldwin [email protected] MEXICO CITY, Mexico and GURNEE, Ill. — In 2011 and 2013, Six Flags partnered with Rocky Mountain Con- struction and Alan Shilke of Ride Centerline to transform two aging monolithic wooden coasters into spectacular hits. Redesigning the Texas Giant at Six Flags Over Texas and Rat- tler at Fiesta Texas into New Texas Giant and Iron Rattler utilizing I-Box track with a dramatic new layout met with overwhelming approval from their respective audiences. Six Flags Mexico transforms Previously, the high mainte- their aging wooden roller- nance issues along with rider coaster into the highly-suc- dissatisfaction with a rougher cessful Medusa Steel Coaster ride was indicative of a need using Rocky Mountain Con- for change. Long past their struction’s I-Box track. The peak, the mega-woodies saw ride is now faster and features new life instead of a wrecking three barrel rolls, including ball. one right off the lift. At right, This summer, the two Six Flags Great America de- teams paired up again, this buted Goliath. The zero-G stall time doing one I-Box transfor- is one of the longest spans of mation and another new ride upside-down excitement on built from the ground up. any coaster seen before. Both Medusa, a wooden coaster rides opened to rave reviews. -

Attractions Management Issue 1 2018

www.attractionsmanagement.com @attractionsmag VOL23 Q1 2018 CLICK TO PLAY VIDEO www.simworx.co.uk www.simworx.co.uk [email protected] www.attractionsmanagement.com @attractionsmag VOL23 1 2018 HOT TOPIC Tackling EPIC WATERS the plastic Texas waterpark problem lives up to its name BOB WHITE on Village Roadshow’s growth ambitions BEAR GRYLLS Survivalist launches new Merlin midway 2018’s top new attractions and coasters Specialist Visitor Attraction display products for System Integrators & Visitors Proven projector solutions, delivering breath-taking imagery for the modern, immersive Visitor Attraction venue – Theme Parks, Planetariums & Museums ΖQWURGXFLQJWKHZRUOGȇVȴUVW.'/3 Laser Projector - The INSIGHT LASER 8K Providing an ultra-high 8K resolution (7680 X 4320) of 33-million pixels through 25,000 ANSI lumens of solid-state laser- phosphor illumination www.digitalprojection.com 8K 4K, HD DLP LASER PHOSPHOR PROJECTORS 20,000 HOURS ILLUMINATION blog.attractionsmanagement.com DISNEY HOSPITALS Disney has announced a $100m fund to transform childrens’ experience of hospital stays. The five-year initiative will start in Texas and roll-out worldwide. We love it, but we’d also like to see a dual focus on prevention, to stop kids getting sick in the first place imes when children are in hospital are some of the impact on recovery and wellbeing and we hope a research most upsetting and stressful for everyone involved. project will run alongside this initiative to assess the impact T Now Disney has announced it will create a new of both environmental and psychological interventions on the programme for children’s hospitals to help ease this health of children. -

Summer 2019 Edition

August 2019 Session 2 Quad Sports Sizzle! Mike B and campers heat up summer camp with super sports. Story by Camp Staff from Summer 2019 1 Sports in the Quad area of the campus is one of the centerpieces of Camp College, literally. The classes (that range from Flag Football to Beach Sports to Soccer) have been run by a variety of teachers and counselors over the summers, but one mainstay has been the legendary Mike Belfiore. With the skill, talent and creativity you would expect from a PE teacher, Mike makes summer classes outside fun to be in. Summer is all about being outside, getting sweaty, and getting exercise! Mike and brothers James and Lorenzo provide a time and place for campers to experience the fun of playground games. Shady, then sunny as the day goes on, the quad offers a break from cell phones, game devices and summer math packets. One long time camper describes Mike’s classes as creating “Fond, entertaining memories and a time where everyone could feel included!” It seems as though any camper, experienced in athletics or not, can enjoy the Quad classes. In closing, this dynamic set of classes is one you’ll want to sign up for next summer! Ask your friends which classes they enjoyed best. And don’t forget, bring a water bottle. THIS SUMMER’S TOP STORIES Crazy for Kooky Science story by Camp ‘zine Staff Joseph Violi is clearly having a lot of fun in this class. It looks like he is making some type of slime - and a mess! Miss Emily is the teacher for this class and we’re surprised she can handle all these noisy kids! But she does, and boy do they love the class! From science to silly, this class is a blast. -

PRODUCT OVERVIEW Crowd Pulling Sensations at Their Best 48 WORLD RECORDS

PRODUCT OVERVIEW Crowd pulling sensations at their best 48 WORLD RECORDS ROLLER COASTERS Widely regarded as the key attraction in any amusement or theme park, many types of roller coasters have been developed by INTAMIN to provide thrills and excitement for all ages. This product line is and will continue to be refined byINTAMIN on a mission to always set new limits. Some of the worldwide achievements reached so far are: Highest and Fastest Strongest LSM Launch Roller Coaster Highest Number of Track Fastest Multi Launch Coaster Intersections (116 times) Fastest Catapult Drive (LSM) 48 World Records Longest Launch Coaster 47 Global Awards Highest Inversion LSM LAUNCH COASTER Explosive accelerations, steady cruising speeds, ground breaking maneuvers and near miss elements for a perfect thrilling experience granted by the strongest LSM drive system on the market. Available in a single or multi launch, swing and / or dueling configuration. REVERSE FREE FALL COASTER SURF RIDER IMPULSE COASTER Unique weightless free fall journey, Acceleration, spinning and Suspended coaster with vertical free falls, with forward-backward seating. weightlessness at different heights. multiple launches and twists. ATV JET SKI VERTICAL LIFT COASTER FAMILY LAUNCH COASTER Exciting configurations paired with a Friction wheel-driven launches for a genuine first acceleration followed by one or more booster unique vertical lift system (LSM or chain). sections. Close to the ground track to enhance the feeling of speed for a true family attraction. Family Family Thrill Thrill Insane GIGA COASTER MEGA COASTER ULTRA COASTER Record-breaking heights with blistering Going big in height, speed, airtime and Medium-size coaster packed with air- speed, airtime and fast transitions. -

Your Partner for Quality Television

Your Partner for Quality Television DW Transtel is your source for captivating documentaries and a range of exciting programming from the heart of Europe. Whether you are interested in science, nature and the environment, history, the arts, culture and music, or current affairs, DW Transtel has hundreds of programs on offer in English, Spanish and Arabic. Versions in other languages including French, German, Portuguese and Russian are available for selected programs. DW Transtel is part of Deutsche Welle, Germany’s international broadcaster, which has been producing quality television programming for decades. Tune in to the best programming from Europe – tune in to DW Transtel. SCIENCE TECHNOLOGY MEDICINE NATURE ENVIRONMENT ECONOMICS AGRICULTURE WORLD ISSUES HISTORY ARTS CULTURE PEOPLE PLACES CHILDREN YOUTH SPORTS MOTORING M U S I C FICTION ENTERTAINMENT For screening and comparehensive catalog information, please register online at b2b.dw.com DW Transtel | Sales and Distribution | 53110 Bonn, Germany | [email protected] Key VIDEO FORMAT RIGHTS 4K Ultra High Definition WW Available worldwide HD High Definition VoD Video on demand SD Standard Definition M Mobile IFE Inflight LR Limited rights, please contact your regional distribution partner. For screening and comparehensive catalog information, please register online at b2b.dw.com DW Transtel | Sales and Distribution | 53110 Bonn, Germany | [email protected] Table of Contents SCIENCE ORDER NUMBER FORMAT RUNNING TIME Science Workshop 262634 Documentary 15 x 30 min. The Miraculous Cosmos of the Brain 264102 Documentary 13 x 30 min. Future Now – Innovations Shaping Tomorrow 244780 Clips 20 x 5-8 min. Great Moments in Science and Technology 244110 Documentary 98 x 15 min.