Book Reviews

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dr Sally Mapstone “Myllar's and Chepman's Prints” (Strand: Early Printing)

Programme MONDAY 30 JUNE 10.00-11.00 Plenary: Dr Sally Mapstone “Myllar's and Chepman's Prints” (Strand: Early Printing) 11.00-11.30 Coffee 11.30-1.00 Session 1 A) Narrating the Nation: Historiography and Identity in Stewart Scotland (c.1440- 1540): a) „Dream and Vision in the Scotichronicon‟, Kylie Murray, Lincoln College, Oxford. b) „Imagined Histories: Memory and Nation in Hary‟s Wallace‟, Kate Ash, University of Manchester. c) „The Politics of Translation in Bellenden‟s Chronicle of Scotland‟, Ryoko Harikae, St Hilda‟s College, Oxford. B) Script to Print: a) „George Buchanan‟s De jure regni apud Scotos: from Script to Print…‟, Carine Ferradou, University of Aix-en-Provence. b) „To expone strange histories and termis wild‟: the glossing of Douglas‟s Eneados in manuscript and print‟, Jane Griffiths, University of Bristol. c) „Poetry of Alexander Craig of Rosecraig‟, Michael Spiller, University of Aberdeen. 1.00-2.00 Lunch 2.00-3.30 Session 2 A) Gavin Douglas: a) „„Throw owt the ile yclepit Albyon‟ and beyond: tradition and rewriting Gavin Douglas‟, Valentina Bricchi, b) „„The wild fury of Turnus, now lyis slayn‟: Chivalry and Alienation in Gavin Douglas‟ Eneados‟, Anna Caughey, Christ Church College, Oxford. c) „Rereading the „cleaned‟ „Aeneid‟: Gavin Douglas‟ „dirty‟ „Eneados‟, Tom Rutledge, University of East Anglia. B) National Borders: a) „Shades of the East: “Orientalism” and/as Religious Regional “Nationalism” in The Buke of the Howlat and The Flyting of Dunbar and Kennedy‟, Iain Macleod Higgins, University of Victoria . b) „The „theivis of Liddisdaill‟ and the patriotic hero: contrasting perceptions of the „wickit‟ Borderers in late medieval poetry and ballads‟, Anna Groundwater, University of Edinburgh 1 c) „The Literary Contexts of „Scotish Field‟, Thorlac Turville-Petre, University of Nottingham. -

620 Httpswwwopeneduopenlearncreate Cmid146877 2020-01-09 13-57-50 Rs6288 1..30

OpenLearn Works Unit 13: Storytelling, comedy and popular culture by Donald Smith Copyright © 2019 The Open University 2 of 30 http://www.open.edu/openlearncreate/course/view.php?id=2705 Thursday 9 January 2020 Contents Introduction 4 13. Introductory handsel 5 13.1 The resilience of oral storytelling 8 13.2 Humorous folk tales in Scots 13 13.3. Music halls and the dominance of English 17 13.4 From Leonard to Bissett 21 13.5 What I have learned 28 Further Research 29 References 29 Acknowledgements 29 3 of 30 http://www.open.edu/openlearncreate/course/view.php?id=2705 Thursday 9 January 2020 Introduction Introduction Storytelling belongs first of all to an oral culture, which is not written down, remaining fluid, and relatively uncontrolled. When something is written down in a manuscript or a book, there is a standard against which other versions can be compared or corrected. Since the emergence of writing, political, social and religious institutions have privileged written records over oral memory and tradition. This has had a huge influence on the survival and evolution of the Scots language. Having lost its role as a contemporary written language in the 17th century, Scots continued to thrive as a spoken tung. This led to Scots often being associated with aspects of culture that were not sanctioned by authority, or explicitly dissident. To gie tung or ‘raise your voice’ could be seen as anti-authority, an expression of cultural resistance and human freedom. Consequently, people were told to curb or haud their tungs. And the forms of punishment administered by local courts included restraining the tongue, as for example with a Scold’s Bridle. -

Nairn South Strategic Masterplan, PDF 1.29 MB Download

Table of Contents 1. Introduction................................................................................................................................4 2. Policy.........................................................................................................................................4 Highland-wide Local Development Plan (April 2012).....................................................................4 Nairnshire Local Plan (As continued in force) (April 2012).............................................................4 Supplementary Guidance..............................................................................................................5 3. Context and Development factors..............................................................................................6 General .........................................................................................................................................6 Access, Core Paths and Green Networks .....................................................................................7 Noise.............................................................................................................................................8 Landscaping, Planting and Open Space........................................................................................9 Flood Risk and drainage .............................................................................................................10 Physical constraint ......................................................................................................................10 -

The Culture of Literature and Language in Medieval and Renaissance Scotland

The Culture of Literature and Language in Medieval and Renaissance Scotland 15th International Conference on Medieval and Renaissance Scottish Literature and Language (ICMRSLL) University of Glasgow, Scotland, 25-28 July 2017 Draft list of speakers and abstracts Plenary Lectures: Prof. Alessandra Petrina (Università degli Studi di Padova), ‘From the Margins’ Prof. John J. McGavin (University of Southampton), ‘“Things Indifferent”? Performativity and Calderwood’s History of the Kirk’ Plenary Debate: ‘Literary Culture in Medieval and Renaissance Scotland: Perspectives and Patterns’ Speakers: Prof. Sally Mapstone (Principal and Vice-Chancellor of the University of St Andrews) and Prof. Roger Mason (University of St Andrews and President of the Scottish History Society) Plenary abstracts: Prof. Alessandra Petrina: ‘From the margins’ Sixteenth-century Scottish literature suffers from the superimposition of a European periodization that sorts ill with its historical circumstances, and from the centripetal force of the neighbouring Tudor culture. Thus, in the perception of literary historians, it is often reduced to a marginal phenomenon, that draws its force solely from its powers of receptivity and imitation. Yet, as Philip Sidney writes in his Apology for Poetry, imitation can be transformed into creative appropriation: ‘the diligent imitators of Tully and Demosthenes (most worthy to be imitated) did not so much keep Nizolian paper-books of their figures and phrases, as by attentive translation (as it were) devour them whole, and made them wholly theirs’. The often lamented marginal position of Scottish early modern literature was also the key to its insatiable exploration of continental models and its development of forms that had long exhausted their vitality in Italy or France. -

The River Tay - Its Silvery Waters Forever Linked to the Picts and Scots of Clan Macnaughton

THE RIVER TAY - ITS SILVERY WATERS FOREVER LINKED TO THE PICTS AND SCOTS OF CLAN MACNAUGHTON By James Macnaughton On a fine spring day back in the 1980’s three figures trudged steadily up the long climb from Glen Lochy towards their goal, the majestic peak of Ben Lui (3,708 ft.) The final arête, still deep in snow, became much more interesting as it narrowed with an overhanging cornice. Far below to the West could be seen the former Clan Macnaughton lands of Glen Fyne and Glen Shira and the two big Lochs - Fyne and Awe, the sites of Fraoch Eilean and Dunderave Castle. Pointing this out, James the father commented to his teenage sons Patrick and James, that maybe as they got older the history of the Clan would interest them as much as it did him. He told them that the land to the West was called Dalriada in ancient times, the Kingdom settled by the Scots from Ireland around 500AD, and that stretching to the East, beyond the impressively precipitous Eastern corrie of Ben Lui, was Breadalbane - or upland of Alba - part of the home of the Picts, four of whose Kings had been called Nechtan, and thus were our ancestors as Sons of Nechtan (Macnaughton). Although admiring the spectacular views, the lads were much more keen to reach the summit cairn and to stop for a sandwich and some hot coffee. Keeping his thoughts to himself to avoid boring the youngsters, and smiling as they yelled “Fraoch Eilean”! while hurtling down the scree slopes (at least they remembered something of the Clan history!), Macnaughton senior gazed down to the source of the mighty River Tay, Scotland’s biggest river, and, as he descended the mountain at a more measured pace than his sons, his thoughts turned to a consideration of the massive influence this ancient river must have had on all those who travelled along it or lived beside it over the millennia. -

1427 to 1453

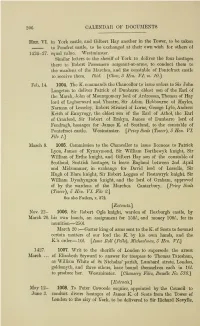

206 CALENDAE OF DOCUMENTS Hen. VI. in York castle, and Gilbert Hay another in the Tower, to be taken to Pomfret castle, to be exchanged at their own wish for others of 1426-27. equal value. Westminster. Similar letters to the sheriff of York to deliver the four hostages there to Eobert Passemere sergeant-at-arms, to conduct them to the wardens of the Marches, and the constable of Pontefract castle to receive them. IMd. {^Closc, 5 Hen. VI. m. JO.] Feb. 14. 1004. The K. commands the Chancellor to issue orders to Sir John Langeton to deliver Patrick of Dunbarre eldest son of the Earl of the March, John of Mountgomery lord of Ardrossan, Thomas of Hay lord of Loghorward and Yhestre, Sir Adam Hebbourne of Hayles, Norman of Lesseley, Eobert Stiward of Lome, George Lyle, Andrew Keith of Ennyrugy, the eldest son of the Earl of Athol, the Earl of Crauford, Sir Eobert of Erskyn, James of Dunbarre lord of Fendragh, hostages for James K. of Scotland, to the constable of Pontefract castle. Westminster. {^Privy Seals (Toiuer), 5 Hen. VI. File I] March 8. 1005. Commission to the Chancellor to issue licences to Patrick Lyon, James of Kynnymond, Sir William Borthewyk knight, Sir William of Erthe knight, and Gilbert Hay son of the constable of Scotland, Scottish hostages, to leave England between 2nd April and Midsummer, in exchange for David lord of Lesselle, Sir Hugh of Blare knight. Sir Eobert Loggan of Eestawryk knight, Sir William Dysshyngton knight, and the lord of Graham, approved of by the wardens of the Marches. -

SCOTTISH TEXT SOCIETY Old Series

SCOTTISH TEXT SOCIETY Old Series Skeat, W.W. ed., The kingis quiar: together with A ballad of good counsel: by King James I of Scotland, Scottish Text Society, Old Series, 1 (1884) Small, J. ed., The poems of William Dunbar. Vol. I, Scottish Text Society, Old Series, 2 (1883) Gregor, W. ed., Ane treatise callit The court of Venus, deuidit into four buikis. Newlie compylit be Iohne Rolland in Dalkeith, 1575, Scottish Text Society, Old Series, 3 (1884) Small, J. ed., The poems of William Dunbar. Vol. II, Scottish Text Society, Old Series, 4 (1893) Cody, E.G. ed., The historie of Scotland wrytten first in Latin by the most reuerend and worthy Jhone Leslie, Bishop of Rosse, and translated in Scottish by Father James Dalrymple, religious in the Scottis Cloister of Regensburg, the zeare of God, 1596. Vol. I, Scottish Text Society, Old Series, 5 (1888) Moir, J. ed., The actis and deisis of the illustere and vailzeand campioun Schir William Wallace, knicht of Ellerslie. By Henry the Minstrel, commonly known ad Blind Harry. Vol. I, Scottish Text Society, Old Series, 6 (1889) Moir, J. ed., The actis and deisis of the illustere and vailzeand campioun Schir William Wallace, knicht of Ellerslie. By Henry the Minstrel, commonly known ad Blind Harry. Vol. II, Scottish Text Society, Old Series, 7 (1889) McNeill, G.P. ed., Sir Tristrem, Scottish Text Society, Old Series, 8 (1886) Cranstoun, J. ed., The Poems of Alexander Montgomerie. Vol. I, Scottish Text Society, Old Series, 9 (1887) Cranstoun, J. ed., The Poems of Alexander Montgomerie. Vol. -

![[2020] Sc Gla 27 Ca30/19 Judgment of Sheriff S. Reid](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/0820/2020-sc-gla-27-ca30-19-judgment-of-sheriff-s-reid-640820.webp)

[2020] Sc Gla 27 Ca30/19 Judgment of Sheriff S. Reid

SHERIFFDOM OF GLASGOW AND STRATHKELVIN AT GLASGOW [2020] SC GLA 27 CA30/19 JUDGMENT OF SHERIFF S. REID, ESQ in the cause WPH DEVELOPMENTS LIMITED Pursuer against YOUNG & GAULT LLP (IN LIQUIDATION) Defender Act: Mr D Johnston QC; instructed by Mitchells Robertson, Glasgow Alt: Mr S. Manson, Advocate; instructed by DWF, Glasgow Glasgow, 8 April 2020 The sheriff, having resumed consideration of the cause: 1. Repels, in part, the defender’s pleas-in-law numbers 2 & 3 so far as directed at the relevancy of the pursuer’s averments anent prescription; quoad ultra Reserves the defender’s said preliminary pleas; 2. Sustains, in part, the pursuer’s plea-in-law number 5 so far as directed at the relevancy of the defender’s averments anent prescription whereby, Excludes from probation the defender’s averments in Answer 3 from (and including) the words “more particularly…” (on page 5, line 23 of the Record number 16 of process) to the end of the said Answer; quoad ultra Reserves the pursuer’s said preliminary plea; thereafter, 3. Allows parties a proof before answer of their respective remaining averments, reserving, so far as extant, the parties’ preliminary pleas (namely, the defender’s 2 pleas-in-law numbers 2 & 3 and the pursuer’s pleas-in-law numbers 4 & 5), on dates to be hereafter assigned; 4. meantime, Reserves the issue of the expenses of the diet of debate and preparation therefor. NOTE: Summary [1] A patient suffers an internal injury at the hands of a negligent surgeon in the course of a botched operation. -

Poetry: Why? Even Though a Poem May Be Short, Most of the Time You Can’T Read It Fast

2.1. Poetry: why? Even though a poem may be short, most of the time you can’t read it fast. It’s like molasses. Or ketchup. With poetry, there are so many things to take into consideration. There is the aspect of how it sounds, of what it means, and often of how it looks. In some circles, there is a certain aversion to poetry. Some consider it outdated, too difficult, or not worth the time. They ask: Why does it take so long to read something so short? Well, yes, it is if you are used to Twitter, or not used to poetry. Think about the connections poetry has to music. Couldn’t you consider some of your favorite lyrics poetry? 2Pac, for example, wrote a book of poetry called The Rose that Grew from Concrete. At many points in history across many cultures, poetry was considered the highest form of expression. Why do people write poetry? Because they want to and because they can… (taking the idea from Federico García Lorca en his poem “Lucía Martínez”: “porquequiero, y porquepuedo”) You ask yourself: Why do I need to read poetry? Because you are going to take the CLEP exam. Once you move beyond that, it will be easier. Some reasons why we write/read poetry: • To become aware • To see things in a different way • To put together a mental jigsaw puzzle • To move the senses • To provoke emotions • To find order 2.2. Poetry: how? If you are not familiar with poetry, you should definitely practice reading some before you take the exam. -

Drunkenness and Ambition in Early Seventeenth-Century Scottish Literature," Studies in Scottish Literature: Vol

Studies in Scottish Literature Volume 35 | Issue 1 Article 12 2007 Drunkenness and Ambition in Early Seventeenth- Century Scottish Literature Sally Mapstone St. Hilda's College, Oxford Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/ssl Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Mapstone, Sally (2007) "Drunkenness and Ambition in Early Seventeenth-Century Scottish Literature," Studies in Scottish Literature: Vol. 35: Iss. 1, 131–155. Available at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/ssl/vol35/iss1/12 This Article is brought to you by the Scottish Literature Collections at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Studies in Scottish Literature by an authorized editor of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Sally Mapstone Drunkenness and Ambition in Early Seventeenth-Century Scottish Literature Among the voluminous papers of William Drummond of Hawthomden, not, however with the majority of them in the National Library of Scotland, but in a manuscript identified about thirty years ago and presently in Dundee Uni versity Library, 1 is a small and succinct record kept by the author of significant events and moments in his life; it is entitled "MEMORIALLS." One aspect of this record puzzled Drummond's bibliographer and editor, R. H. MacDonald. This was Drummond's idiosyncratic use of the term "fatall." Drummond first employs this in the "Memorialls" to describe something that happened when he was twenty-five: "Tusday the 21 of Agust [sic] 1610 about Noone by the Death of my father began to be fatall to mee the 25 of my age" (Poems, p. -

Inventory Acc.3721 Papers of the Scottish Secretariat and of Roland

Inventory Acc.3721 Papers of the Scottish Secretariat and of Roland Eugene Muirhead National Library of Scotland Manuscripts Division George IV Bridge Edinburgh EH1 1EW Tel: 0131-466 2812 Fax: 0131-466 2811 E-mail: [email protected] © Trustees of the National Library of Scotland Summary of Contents of the Collection: BOXES 1-40 General Correspondence Files [Nos.1-1451] 41-77 R E Muirhead Files [Nos.1-767] 78-85 Scottish Home Rule Association Files [Nos.1-29] 86-105 Scottish National Party Files [1-189; Misc 1-38] 106-121 Scottish National Congress Files 122 Union of Democratic Control, Scottish Federation 123-145 Press Cuttings Series 1 [1-353] 146-* Additional Papers: (i) R E Muirhead: Additional Files Series 1 & 2 (ii) Scottish Home Rule Association [Main Series] (iii) National Party of Scotland & Scottish National Party (iv) Scottish National Congress (v) Press Cuttings, Series 2 * Listed to end of SRHA series [Box 189]. GENERAL CORRESPONDENCE FILES BOX 1 1. Personal and legal business of R E Muirhead, 1929-33. 2. Anderson, J W, Treasurer, Home Rule Association, 1929-30. 3. Auld, R C, 1930. 4. Aberdeen Press and Journal, 1928-37. 5. Addressall Machine Company: advertising circular, n.d. 6. Australian Commissioner, 1929. 7. Union of Democratic Control, 1925-55. 8. Post-card: list of NPS meetings, n.d. 9. Ayrshire Education Authority, 1929-30. 10. Blantyre Miners’ Welfare, 1929-30. 11. Bank of Scotland Ltd, 1928-55. 12. Bannerman, J M, 1929, 1955. 13. Barr, Mrs Adam, 1929. 14. Barton, Mrs Helen, 1928. 15. Brown, D D, 1930. -

Roll of Honour of Nairnshire

u NAIRNSHIRE ROLL OF . HONOUR. ROLL OF HONOUR OF NAIRNSHIRE Containing Names and Addresses of those in each Parish who are serving their King and Country in the great European War. Every effort has been made to give a complete and accurate Roll, but the Pub- lisher does not hold himself responsible for any omissions or errors* T. R RAMAGE, Nairn, March, 191J. PRINTED AT THE COUNTY PRESS, NAIRN. Nairnshire Roll of Honour. T"\ AIRNSHIRE has responded nobly to the call of her King statistics herewith | I and country, and from the JL / given, it will be seen that the county has reason to be proud of her position, and should rank amongst those counties in Britain that have given the largest percent- age of their manhood in this the most serious time of Britain's history. Each parish is given separately, so that it can be seen at a glance how many have gone out from these districts, and to what units they belong. The Navy is largely repre- sented ; also the Seaforths and Camerons, for which Nairn- shire is part of the recruiting area. The total number serving is 894, to which Nairn Parish contributes 548, Auldearn Parish 112, Cawdor Parish 95, Croy Parish (Nairnshire part) 40, Ardclach Parish, 40. Of this total 163 belong to the Naval Services, 288 to the Regular and Kitchener's Armies, and 439 to the Terri- torial and other voluntary services. The above figures represent a percentage of 9.59 over the whole county ; 20.65 of the male population ; and 64.73 of the latter from 18 to 40 years of age.