20200418 Arco Notation and Style Guide

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The KNIGHT REVISION of HORNBOSTEL-SACHS: a New Look at Musical Instrument Classification

The KNIGHT REVISION of HORNBOSTEL-SACHS: a new look at musical instrument classification by Roderic C. Knight, Professor of Ethnomusicology Oberlin College Conservatory of Music, © 2015, Rev. 2017 Introduction The year 2015 marks the beginning of the second century for Hornbostel-Sachs, the venerable classification system for musical instruments, created by Erich M. von Hornbostel and Curt Sachs as Systematik der Musikinstrumente in 1914. In addition to pursuing their own interest in the subject, the authors were answering a need for museum scientists and musicologists to accurately identify musical instruments that were being brought to museums from around the globe. As a guiding principle for their classification, they focused on the mechanism by which an instrument sets the air in motion. The idea was not new. The Indian sage Bharata, working nearly 2000 years earlier, in compiling the knowledge of his era on dance, drama and music in the treatise Natyashastra, (ca. 200 C.E.) grouped musical instruments into four great classes, or vadya, based on this very idea: sushira, instruments you blow into; tata, instruments with strings to set the air in motion; avanaddha, instruments with membranes (i.e. drums), and ghana, instruments, usually of metal, that you strike. (This itemization and Bharata’s further discussion of the instruments is in Chapter 28 of the Natyashastra, first translated into English in 1961 by Manomohan Ghosh (Calcutta: The Asiatic Society, v.2). The immediate predecessor of the Systematik was a catalog for a newly-acquired collection at the Royal Conservatory of Music in Brussels. The collection included a large number of instruments from India, and the curator, Victor-Charles Mahillon, familiar with the Indian four-part system, decided to apply it in preparing his catalog, published in 1880 (this is best documented by Nazir Jairazbhoy in Selected Reports in Ethnomusicology – see 1990 in the timeline below). -

Making Music from Around the World

The Birmingham Botanical Gardens Making Music From Around The World The Birmingham Botanical Gardens & Glasshouses Introduction In the Music National Curriculum, one of the general requirements for study throughout Key Stages 1, 2 and 3 is the inclusion of music from ‘a variety of cultures, Western and non-Western’. However, it is not always that easy to find ways of introducing a multicultural dimension to the teaching of music in the classroom. At the Botanical Gardens we have an exciting collection of musical instruments made from natural materials, which come from around the world. These instruments are available for workshop sessions, which allow the pupils to explore a new world of sound and learn more about the places they come from and the people who make them. This booklet describes the fascinating instruments available; the plant materials used in their construction and practical fun activities that can be carried out with the pupils at the Gardens. Acknowledgements Many thanks must go to Andy Wilson from Knock on Wood for supplying us with most of our instruments and helpful background information. Musical Instruments Africa Bean Pod Rattle Perhaps the simplest rattle of them all. This example is the pod of the Royal Poinciana tree from Madagascar. Baobab Rattle Another simple rattle using the fruit and seeds of the Baobab tree. Another kind of seed pod rattle. Possibly using Capala fruits from the Passiflora group of plants threaded onto a stick. Nyatiti Uses a calabash as the body of the instrument which acts as the sound box. Musical Instruments Africa Caxixi (Kasheeshee) A strong, split cane woven basket rattle from Cameroon. -

Following the Trail of the Snake: a Life History of Cobra Mansa “Cobrinha” Mestre of Capoeira

ABSTRACT Title of Document: FOLLOWING THE TRAIL OF THE SNAKE: A LIFE HISTORY OF COBRA MANSA “COBRINHA” MESTRE OF CAPOEIRA Isabel Angulo, Doctor of Philosophy, 2008 Directed By: Dr. Jonathan Dueck Division of Musicology and Ethnomusicology, School of Music, University of Maryland Professor John Caughey American Studies Department, University of Maryland This dissertation is a cultural biography of Mestre Cobra Mansa, a mestre of the Afro-Brazilian martial art of capoeira angola. The intention of this work is to track Mestre Cobrinha’s life history and accomplishments from his beginning as an impoverished child in Rio to becoming a mestre of the tradition—its movements, music, history, ritual and philosophy. A highly skilled performer and researcher, he has become a cultural ambassador of the tradition in Brazil and abroad. Following the Trail of the Snake is an interdisciplinary work that integrates the research methods of ethnomusicology (oral history, interview, participant observation, musical and performance analysis and transcription) with a revised life history methodology to uncover the multiple cultures that inform the life of a mestre of capoeira. A reflexive auto-ethnography of the author opens a dialog between the experiences and developmental steps of both research partners’ lives. Written in the intersection of ethnomusicology, studies of capoeira, social studies and music education, the academic dissertation format is performed as a roda of capoeira aiming to be respectful of the original context of performance. The result is a provocative ethnographic narrative that includes visual texts from the performative aspects of the tradition (music and movement), aural transcriptions of Mestre Cobra Mansa’s storytelling and a myriad of writing techniques to accompany the reader in a multi-dimensional journey of multicultural understanding. -

Exhibition Music Workshops

EXHIBITION an interactive exhibition with contemporary musical instruments, sound installations and devices, audiovisual displays, games and talks. MUSIC concert with Victor Gama’s unique Pangeia Instrumentos and music compositions. WORKSHOPS music and instrument building workshops for kids and adults in the gallery space or at local schools. Paul Hamlyn Hall, Royal Opera House, Londres, Reino Unido Paul Hamlyn Hall, Royal Opera House, Londres, Reino Unido 'the event's most impressive and resonant mix of sound, vision and concept was Instrumentos, an exhibition/performance in the beautiful Paul Hamlyn Hall by Angola-born inventor and musician Victor Gama. Each instrument is a beautiful object; each implies a different audio-visual journey that's both ethnic and high tech.' The Guardian VISION A space of free experimentation and performance for the visitor INSTRUMENTOS is an exhibition of the The new digital technologies have allowed Pangeia Instrumentos series of the de-materialization of the musical contemporary musical instruments. These instrument and consequently making are acoustic musical instruments, sound music without the object. In designing devices and sound installations designed new instruments we make use of those and built through a process of same technologies to re-materialize the experimentation with design, sound and object while using form and design as music. variables in writing new music. Hub National Centre for Craft & Design, United Kingdom EXHIBITION Since 1999 PangeiArt has developed an award winning exhibition that is part of a collection of more then thirty unique contemporary musical instruments designed by musician/composer Victor Gama. Among the instruments are the Toha, a visitors are invited to touch and play the type of harp made with 42 strings to be instruments on display. -

K-REV: the KNIGHT-REVISION of HORNBOSTEL-SACHS a System for Musical Instrument Classification by Roderic Knight, Oberlin College, © 2015

K-REV: The KNIGHT-REVISION OF HORNBOSTEL-SACHS A system for musical instrument classification by Roderic Knight, Oberlin College, © 2015 Organology, or the scientific study of musical instruments, has ancient roots. In China, a system of classification known as the pa yin or “eight sounds” was devised in the third millennium BCE. It was based on eight materials used in instrument construction (but not necessarily in sound production) and allied to other physical and metaphysical phenomena. More recently, but still in ancient times, the Indian sage Bharata outlined in his Natyashastra (ca. 200 CE) a classification based on how the sound is produced: by blowing (sushira), setting a string in motion (tata), hitting a stretched skin (avanaddha), or hitting something solid (ghana). This system endures as a worldwide phenomenon today because Victor Mahillon adopted it for his catalog of the instruments in the Brussels Conservatory museum in the 19th century, and because his system was picked up in turn by Erich M. von Hornbostel and Curt Sachs in producing their seminal Systematik der Musikinstrumente (Classification of Musical Instruments) in 1914. Hornbostel and Sachs sought to universalize the Mahillon catalog by developing a hierarchy of terms that could encompass all the methods of sound production known to humankind. They used three of Mahillon’s terms: aerophone, for the “winds and brass” of the orchestra and all other instruments that produce a sound by exciting the air directly; chordophone, for all stringed instruments (including the keyboards); and membranophone for drums. Hornbostel and Sachs replaced Mahillon’s fourth term, autophone (for instruments whose body itself, or some part of the body, produces the sound – the Indian ghana type), with their newly coined term, idiophone, to avoid the ambiguous implication that an “autophone” might sound by itself. -

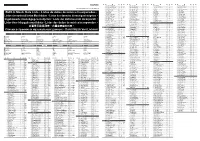

Built-In Music Data Lists • Listas De Datos De Música Incorporados

14M10APPEND-WL-1A.fm 1 ページ 2018年8月9日 木曜日 午後12時8分 269 WARM SYNTH-BRASS 1 62 35 381 SINE LEAD 80 2 494 SALUANG 77 43 608 GM TENOR SAX 66 0 270 WARM SYNTH-BRASS 2 62 38 DSP 382 VELO.SINE LEAD 80 44 495 SULING BAMBOO 2 77 42 609 GM BARITONE SAX 67 0 271 ANALOG SYNTH-BRASS 62 36 383 SYNTH SEQUENCE 80 8 496 OUD 1 105 11 610 GM OBOE 68 0 EN/ES/DE/FR/NL/IT/SV/PT/CN/TW/RU/TR 272 80'S SYNTH-BRASS 62 2 384 SEQUENCE SAW 81 15 497 OUD 2 105 42 611 GM ENGLISH HORN 69 0 273 TRANCE BRASS 63 32 385 SEQUENCE SINE 80 7 498 SAZ 15 4 612 GM BASSOON 70 0 274 TRUMPET 1 56 32 DSP 386 8BIT ARPEGGIO 1 80 9 499 KANUN 1 15 5 613 GM CLARINET 71 0 Built-in Music Data Lists • Listas de datos de música incorporados • 275 TRUMPET 2 56 2 387 8BIT ARPEGGIO 2 80 45 500 KANUN 2 15 33 614 GM PICCOLO 72 0 276 TRUMPET 3 56 36 DSP 388 8BIT WAVE 80 35 501 BOUZOUKI 105 43 615 GM FLUTE 73 0 277 MELLOW TRUMPET 56 3 389 SAW ARPEGGIO 1 81 8 502 RABAB 105 44 616 GM RECORDER 74 0 Listen der vorinstallierten Musikdaten • Listes des données de musique intégrées • 278 MUTE TRUMPET 59 1 390 SAW ARPEGGIO 2 81 9 503 KEMENCHE 110 44 617 GM PAN FLUTE 75 0 279 AMBIENT TRUMPET 56 33 DSP 391 VENT LEAD 82 32 504 NEY 1 72 10 618 GM BOTTLE BLOW 76 0 280 TROMBONE 57 32 392 CHURCH LEAD 85 32 505 NEY 2 72 41 619 GM SHAKUHACHI 77 0 Ingebouwde muziekgegevenslijsten • Liste dei dati musicali incorporati • 281 JAZZ TROMBONE 57 33 393 DOUBLE VOICE LEAD 85 34 506 ZURNA 111 9 620 GM WHISTLE 78 0 282 FRENCH HORN 60 32 394 SYNTH-VOICE LEAD 85 1 507 ARABIC ORGAN 16 7 621 GM OCARINA 79 0 283 FRENCH HORN -

TC 1-19.30 Percussion Techniques

TC 1-19.30 Percussion Techniques JULY 2018 DISTRIBUTION RESTRICTION: Approved for public release: distribution is unlimited. Headquarters, Department of the Army This publication is available at the Army Publishing Directorate site (https://armypubs.army.mil), and the Central Army Registry site (https://atiam.train.army.mil/catalog/dashboard) *TC 1-19.30 (TC 12-43) Training Circular Headquarters No. 1-19.30 Department of the Army Washington, DC, 25 July 2018 Percussion Techniques Contents Page PREFACE................................................................................................................... vii INTRODUCTION ......................................................................................................... xi Chapter 1 BASIC PRINCIPLES OF PERCUSSION PLAYING ................................................. 1-1 History ........................................................................................................................ 1-1 Definitions .................................................................................................................. 1-1 Total Percussionist .................................................................................................... 1-1 General Rules for Percussion Performance .............................................................. 1-2 Chapter 2 SNARE DRUM .......................................................................................................... 2-1 Snare Drum: Physical Composition and Construction ............................................. -

CRAIG WOODSON a World Orchestra PREPARING for the EXPERIENCE: Art Form: Music the Music and Instruments Introduced in Dr

C U R R I C U L U M C O N N E C T I O N CRAIG WOODSON A World Orchestra PREPARING FOR THE EXPERIENCE: Art Form: Music The music and instruments introduced in Dr. Craig Style: Classical to Contemporary Woodson’s performance are part of four broad musical Culture: Asia, Africa. Europe and the Americas cultures studied by ethnomusicologists. These include: MEET THE ARTIST: Africa, Asia, Europe, and the Americas. On each of these continents, there exists music which is based on an oral Dr. Craig Woodson, an educator, author, musician, tradition; that is, music learned by listening and then consultant, and musical instrument maker, holds a doctorate imitating what is heard. This is a different approach than in music from U.C.L.A. His career as a musician includes the one traditionally taken in Western art music. In this playing drums with Elvis Presley and Linda Ronstadt. In 1974 tradition, the music is often written down with symbols he founded Ethnomusic, Inc. as an outgrowth of his and students begin their study by learning the written specialization in instrument making, African drumming, and musical language. ethnomusicology. Later these interests took him to Ghana, Music based on an oral tradition is typically passed on West Africa for three years as an invited researcher. In the from master to student and from one generation to the 1980's, he began school presentations on world music, next. This imitative process provides the student with a African drumming, and percussion from around the world. clear model to guide his or her own musical He has facilitated drum circles and has presented workshops development. -

WAVEDRUM Owner's Manaul

Owner´s Manual E 2 1 Thank you for purchasing the Korg WAVEDRUM THE FCC REGULATION WARNING (for USA) dynamic percussion synthesizer. This equipment has been tested and found to comply This owner’s manual contains a great deal of informa- with the limits for a Class B digital device, pursuant tion that will help you understand the WAVEDRUM to Part 15 of the FCC Rules. These limits are and play it to its fullest potential. In order- to ensure designed to provide reasonable protection against that you are taking complete advantage of your harmful interference in a residential installation. This WAVEDRUM, please read this manual carefully and equipment generates, uses, and can radiate radio fre- use the product as directed. quency energy and, if not installed and used in accor- dance with the instructions, may cause harmful interference to radio communications. However, there is no guarantee that interference will not occur in a Precautions particular installation. If this equipment does cause harmful interference to radio or television reception, Location which can be determined by turning the equipment off and on, the user is encouraged to try to correct the Using the unit in the following locations can result in a interference by one or more of the following mea- malfunction. sures: • In direct sunlight • Reorient or relocate the receiving antenna. • Locations of extreme temperature or humidity • Increase the separation between the equipment • Excessively dusty or dirty locations and receiver. • Locations of excessive vibration • Connect the equipment into an outlet on a circuit • Close to magnetic fields different from that to which the receiver is con- Power supply nected. -

~········R.~·~~~ Fiber-Head Connector ______Grating Region

111111 1111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111 US007507891B2 (12) United States Patent (10) Patent No.: US 7,507,891 B2 Lau et al. (45) Date of Patent: Mar. 24,2009 (54) FIBER BRAGG GRATING TUNER 4,563,931 A * 111986 Siebeneiker et al. .......... 841724 4,688,460 A * 8/1987 McCoy........................ 841724 (75) Inventors: Kin Tak Lau, Kowloon (HK); Pou Man 4,715,671 A * 12/1987 Miesak ....................... 398/141 Lam, Kowloon (HK) 4,815,353 A * 3/1989 Christian ..................... 841724 5,012,086 A * 4/1991 Barnard ................... 250/222.1 (73) Assignee: The Hong Kong Polytechnic 5,214,232 A * 5/1993 Iijima et al. ................... 841724 5,381,492 A * 111995 Dooleyet al. ................. 385112 University, Kowloon (HK) 5,410,404 A * 4/1995 Kersey et al. ............... 356/478 5,684,592 A * 1111997 Mitchell et al. ............. 356/493 ( *) Notice: Subject to any disclaimer, the term of this 5,848,204 A * 12/1998 Wanser ........................ 385112 patent is extended or adjusted under 35 5,892,582 A * 4/1999 Bao et al. ................... 356/519 U.S.c. 154(b) by 7 days. 6,201,912 Bl * 3/2001 Kempen et al. ............... 385/37 6,274,801 Bl * 8/2001 Wardley.. ... ... ..... ... ... ... 841731 (21) Appl. No.: 11/723,555 6,411,748 Bl * 6/2002 Foltzer .......................... 38517 6,797,872 Bl 9/2004 Catalano et al. (22) Filed: Mar. 21, 2007 6,984,819 B2 * 112006 Ogawa .................. 250/227.21 7,002,672 B2 2/2006 Tsuda (65) Prior Publication Data 7,015,390 Bl * 3/2006 Rogers . ... ... ... ..... ... ... ... 841723 7,027,136 B2 4/2006 Tsai et al. -

Culture Box: Brazil

INTRODUCTION: Brazil, officially the Federative Republic of Brazil (Portuguese: República Federativa do Brasil, is the largest country in both South & and Latin America. THIS BOX INCLUDES: 1. Portuguese – English Dictionary 2. Map 3. Currency 4. Pernambuco book and CD 5. Bahia doll – small 6. Decorative bowl 7. Capoeira 8. Toucan magnet 9. Music CD 10. Flag 11. Images from Brazil Culture Box: Brazil PORTUGUESE – ENGLISH DICTIONARY DESCRIPTION The item is a Portuguese to English dictionary. Culture Box: Brazil FLAG DESCRIPTION The item is a large Brazilian flag. This design was started in 1889 with 21 stars, and this 27 star version was adopted in 1992. The stars in the celestial sphere at the center represent the states of the country. The green field represented the family of Pedro I, first emperor of Brazil. The gold diamond represented the family of Maria Leopoldina, the wife of Pedro I. Culture Box: Brazil CURRENCY DESCRIPTION The Brazilian centavos are the sub-units of the Brazilian real (reais, pl.). Modern Reais were adopted in 1994. One 2R$ bill is also included Culture Box: Brazil BAHIA DOLL DESCRIPTION This miniature Bahia doll models the types of blouses, skirts, and head wraps worn by women in the Bahia state during past centuries. While this type of dress may be worn today, it may be found more likely in ceremonial and folk holidays or events. These are popular tourist items from Bahia. Culture Box: Brazil TOUCAN MAGNET DESCRIPTION A colorfully painted and crafted wooden toucan (tucano) with a magnet attached to the back Culture Box: Brazil GOURD BOWL DESCRIPTION Made from a gourd vegetable, this beautifully decorated item has been painted brown with a floral design inside that has been sealed to protect the paint. -

Sample Library Catalog 2006

AMG | ART VISTA | BARDSTOWN AUDIO | BELA D MEDIA | BEST SERVICE | BIG FISH AUDIO | BOLDER SOUNDS | CKSDE DAN DEAN PRO | DISCOVERY SOUND | EASTWEST | FIXED NOISE | GARRITAN | NATIVE INSTRUMENTS | NUMERICAL SOUND POST MUSICAL INSTRUMENTS | PRECISIONSOUND | SONIC IMPLANTS | SONIC REALITY | SONICCOUTURE | SOUNDLABEL SPIRIT CANYON AUDIO | TAP SPACE | VIENNA SYMPHONIC LIBRARY | ZERO-G SAMPLE LIBRARY CATALOG 2006 ForFor more more information: information: www.native-instruments.com www.native-instruments.com Welcome Welcome to the first sample library catalog for the Native Instruments samplers Kontakt, Battery, Kompakt, and Intakt. This catalog features a huge selection of over 130 professional and award winning sample libraries from various sample developers. You will find anything from Orchestral to Electronic, featuring the best available sample libraries in the world. All libraries are specifically designed for the Native Instruments software samplers Kontakt, Battery, Intakt and Kompakt. Some of these libraries contain special versions of Kompakt, Intakt or Kontakt Player and don´t necessarily need the full version of the sampler. Since 2003, Kontakt has fast become the standard in software sampling. Over 50 companies all over the world chose Kontakt or Battery to be their favourite platform for developing sample libraries and over 100.000 users are currently using the Kontakt engine with Kontakt, Kompakt, Intakt, Battery or Kontakt Player. If you want to know more about the sampler products or sample libraries, please visit the Native