Hamad V. Gates and the Continuing Interpretation of Boumediene: a Note on 732 F.3D 990 (9Th Cir

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

FY 2006 from the Dod Iraq Freedom Fund Account To: Reimburse Foreign Governments and Train Foreign Government Military A

06-F-00001 B., Brian - 9/26/2005 10/18/2005 Request all documents pertaining to the Cetacean Intelligence Mission. 06-F-00002 Poore, Jesse - 9/29/2005 11/9/2005 Requesting for documents detailing the total amount of military ordanence expended in other countries between the years of 1970 and 2005. 06-F-00003 Allen, W. - 9/27/2005 - Requesting the signed or unsigned document prepared for the signature of the Chairman, JCS, that requires the members of the armed forces to provide and tell the where abouts of the most wanted Ben Laden. Document 06-F-00004 Ravenscroft, Michele - 9/16/2005 10/6/2005 Request the contracts that have been awarded in the past 3 months to companies with 5000 employees or less. 06-F-00005 Elia, Jacob - 9/29/2005 10/6/2005 Letter is Illegable. 06-F-00006 Boyle Johnston, Amy - 9/28/2005 10/4/2005 Request all documents relating to a Pentagon "Politico-Military" # I- 62. 06-F-00007 Ching, Jennifer Gibbons, Del Deo, Dolan, 10/3/2005 - Referral of documents responsive to ACLU litigation. DIA has referred 21 documents Griffinger & Vecchinone which contain information related to the iraqi Survey Group. Review and return documents to DIA. 06-F-00008 Ching, Jennifer Gibbons, Del Deo, Dolan, 10/3/2005 - Referral of documents responsive to ACLU litigation. DIA has referred three documents: Griffinger & Vecchinone V=322, V=323, V=355, for review and response back to DIA. 06-F-00009 Ravnitzky, Michael - 9/30/2005 10/17/2005 NRO has identified two additional records responsive to a FOIA appeal from Michael Ravnitzky. -

US Failure to Prosecute Senior Officials for Torture

DENIAL OF JUSTICE: THE UNITED STATES’ FAILURE TO PROSECUTE SENIOR OFFICIALS FOR TORTURE1 Materials Submitted in Support of Hearing on Human Rights Situation of People Affected by the U.S. Rendition, Detention, and Interrogation Program before the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights 156th Ordinary Period of Sessions October 23, 2015 Key Facts and Arguments Officials at the highest levels of the United States government created, designed, authorized, and implemented a sophisticated, international criminal program of torture and cruel, inhuman, or degrading treatment or punishment. In August 2014, President Barack Obama conceded that the United States tortured people as part of its “War on Terror.” In December 2014, the Senate Select Committee on Intelligence released the Executive Summary of its report on the Central Intelligence Agency’s detention and interrogation program, providing further evidence of state- sanctioned torture. The Inter-American Commission on Human Rights and other human rights authorities have called on the United States to conduct an in-depth and independent investigation into all allegations of torture and other cruel, inhuman, or degrading treatment or punishment, and to prosecute and punish those responsible. To date, the United States has declined to prosecute any senior officials for these crimes. Moreover, the United States has taken active steps to shield these officials from liability. The United States is thus in violation of its human rights obligations. 1 This submission is an adaptation of the shadow report to the United Nations Committee Against Torture on the Review of the Periodic Report of the United States of America prepared and submitted by Advocates for U.S. -

C:\Documents and Settings\Awarden\Desktop\08

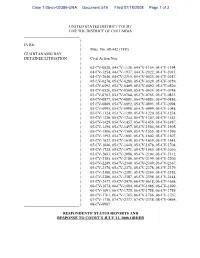

Case 1:05-cv-02386-UNA Document 516 Filed 07/18/2008 Page 1 of 3 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA ____________________________ ) IN RE: ) ) Misc. No. 08-442 (TFH) GUANTANAMO BAY ) DETAINEE LITIGATION ) Civil Action Nos. ) ) 02-CV-0828, 04-CV-1136, 04-CV-1164, 04-CV-1194, ) 04-CV-1254, 04-CV-1937, 04-CV-2022, 04-CV-2035, ) 04-CV-2046, 04-CV-2215, 05-CV-0023, 05-CV-0247, ) 05-CV-0270, 05-CV-0280, 05-CV-0329, 05-CV-0359, ) 05-CV-0392, 05-CV-0409, 05-CV-0492, 05-CV-0520, ) 05-CV-0526, 05-CV-0569, 05-CV-0634, 05-CV-0748, ) 05-CV-0763, 05-CV-0764, 05-CV-0765, 05-CV-0833, ) 05-CV-0877, 05-CV-0881, 05-CV-0883, 05-CV-0886, ) 05-CV-0889, 05-CV-0892, 05-CV-0993, 05-CV-0994, ) 05-CV-0995, 05-CV-0998, 05-CV-0999, 05-CV-1048, ) 05-CV-1124, 05-CV-1189, 05-CV-1220, 05-CV-1234, ) 05-CV-1236, 05-CV-1244, 05-CV-1347, 05-CV-1353, ) 05-CV-1429, 05-CV-1457, 05-CV-1458, 05-CV-1487, ) 05-CV-1490, 05-CV-1497, 05-CV-1504, 05-CV-1505, ) 05-CV-1506, 05-CV-1509, 05-CV-1555, 05-CV-1590, ) 05-CV-1592, 05-CV-1601, 05-CV-1602, 05-CV-1607, ) 05-CV-1623, 05-CV-1638, 05-CV-1639, 05-CV-1645, ) 05-CV-1646, 05-CV-1649, 05-CV-1678, 05-CV-1704, ) 05-CV-1725, 05-CV-1971, 05-CV-1983, 05-CV-2010, ) 05-CV-2083, 05-CV-2088, 05-CV-2104, 05-CV-2112, ) 05-CV-2185, 05-CV-2186, 05-CV-2199, 05-CV-2200, ) 05-CV-2249, 05-CV-2348, 05-CV-2349, 05-CV-2367, ) 05-CV-2370, 05-CV-2371, 05-CV-2378, 05-CV-2379, ) 05-CV-2380, 05-CV-2381, 05-CV-2384, 05-CV-2385, ) 05-CV-2386, 05-CV-2387, 05-CV-2398, 05-CV-2444, ) 05-CV-2477, 05-CV-2479, 06-CV-0618, 06-CV-1668, ) 06-CV-1674, -

Amicus Brief

No. 13-9200 In the Supreme Court of the United States ________________________ ADEL HASSAN HAMAD , PETITIONER v. ROBERT M. GATES , ET AL ., RESPONDENTS _____________ ON PETITION FOR WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE NINTH CIRCUIT ________________________ BRIEF OF AMICUS CURIAE THE CENTER FOR CONSTITUTIONAL RIGHTS IN SUPPORT OF ADEL HASSAN HAMAD’S PETITION FOR A WRIT OF CERTIORARI ________________________ SHAYANA KADIDAL Counsel of Record Center for Constitutional Rights 666 Broadway, 7th Floor New York, NY 10012 [email protected] (212) 614-6438 i QUESTIONS PRESENTED 1. Does 28 U.S.C. § 2241(e)(2) prevent courts from hearing Mr. Hamad’s non-habeas legal claims arising under the United States Constitution and laws of the United States? 2. If 28 U.S.C. § 2241(e)(2) precludes any judicial fo- rum from hearing Mr. Hamad’s claims, does the statute violate the Due Process Clause or constitutional limits on the separation of powers? ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Statement of Interest ....................................................... 1 Summary of Argument ..................................................... 1 Argument ........................................................................... 3 1. The Constitution forbids removal of all federal court jurisdiction over federal questions ............................................... 3 2. On remand the lower courts may avoid addressing the constitutional question of the validity of MCA Sec. 7(b) .............................. 13 Conclusion ........................................................................ 18 iii TABLE OF AUTHORITIES CASES Al-Zahrani v. Rumsfeld , 669 F.3d 315 (D.C. Cir. 2012) ............................... 1, 11, 12 Arar v. Ashcroft , 532 F.3d 157 (2d Cir. 2008), vacated en banc , 585 F.3d 559 (2d Cir. 2009) ............... 17 Arbaugh v. Y & H Corp ., 546 U.S. 500 (2006) ............. -

Press Release

PRESS RELEASE March 14, 2006 CNN's Blitzer Failed To Challenge Gonzales Spin on Guantánamo Summary: In an interview with Attorney General Alberto R. Gonzales, CNN's Wolf Blitzer failed to challenge Gonzales's dubious claim that "if the need were not there for the United States of America to detain people that we catch on the battlefield, then we would not be having to operate" the military prison at Guantánamo Bay, Cuba. Blitzer could have noted recent news reports pointing out that many -- if not a majority -- were not caught by American soldiers on the battlefield but turned over to the U.S. by third parties. In an interview with Attorney General Alberto R. Gonzales on the March 9 edition of CNN's The Situation Room, host Wolf Blitzer failed to challenge Gonzales's dubious claim that "if the need were not there for the United States of America to detain people that we catch on the battlefield, then we would not be having to operate" the military prison at Guantánamo Bay, Cuba. Blitzer could have noted recent news reports, such as those by the National Journal and The New York Times, pointing out that many -- if not a majority, as the National Journal asserts -- were not caught by American soldiers on the battlefield but turned over to the U.S. by third parties. Blitzer also allowed Gonzales to evade his question as to whether or not the treatment of one Guantánamo prisoner, Mohammed al-Qahtani -- as described in a February 27 New Yorker article -- constituted "torture." Rather than answer, Gonzales replied that there is "no way of knowing" the veracity of the report, even though the New Yorker's description of Qahtani's treatment is in line with the findings regarding his treatment contained in a June 2005 Army report by Lt. -

Serious Human Rights Violations Give Rise to a Legal Obligation to Provide a Remedy, and a Remedy Should Be Provided to All Victims

International Center for Transitional Justice After torture U.S. Accountability and the Right to Redress Lisa Magarrell, Lorna Peterson August 2010 Serious human rights TORTURE violations give rise to a legal obligation to EXTRAORDINARY RENDITION provide a remedy, and a remedy should be CRUEL TREATMENT provided to all victims. International Center for Transitional Justice After torture U.S. Accountability and the Right to Redress August 2010 Lisa Magarrell, Lorna Peterson International Center After Torture for Transitional Justice U.S. Accountability and the Right to Redress About the Authors Lisa Magarrell heads ICTJ’s U.S. Accountability Project and is the director of ICTJ’s Program Office. Since joining ICTJ in 2001 she has worked on truth commission processes, repara- tions, and other justice and accountability issues around the world. A human rights lawyer with extensive experience in migrant worker and refugee rights, wartime documentation of human rights abuses, peace processes, and justice for human rights victims in complex contexts, Magarrell has consulted and written widely on reparations, including Memories of an Unfinished Process—Reparations in the Peruvian Transition, which she co-authored. She has law degrees from the University of Iowa (1979), National University of El Salvador (1994), and Columbia University (LLM 2001). Lorna Peterson is a law fellow with the U.S. Accountability Project. She came to ICTJ from the private law firm of Simpson Thacher & Bartlett, LLP, where she worked with the project on a pro bono basis. Her previous experience includes work with Law Center for Families, a legal aid organization in Oakland; the San Francisco Public Defenders; Legal Momentum; and CUSH, a local Liberian community organization. -

Hamad V. Gates

FOR PUBLICATION UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE NINTH CIRCUIT ADEL HASSAN HAMAD, Nos. 12-35395 Plaintiff-Appellant – 12-35489 Cross-Appellee, D.C. No. v. 2:10-cv-00591- MJP ROBERT M. GATES, in his individual capacity; DONALD H. RUMSFELD, in his OPINION individual capacity; PAUL WOLFOWITZ, in his individual capacity; GORDON R. ENGLAND, in his individual capacity; JAMES M. MCGARRAH, in his individual capacity; RICHARD BOWMAN MYERS, in his individual capacity; PETER PACE, in his individual capacity; MICHAEL GLENN MULLEN, in his individual capacity, AKA Mike Mullen; JAMES T. HILL, in his individual capacity; BANTZ J. CRADDOCK, in his individual capacity; GEOFFREY D. MILLER, in his individual capacity; JAY HOOD, in his individual capacity; HARRY B. HARRIS, 2 HAMAD V. GATES JR., in his individual capacity; MARK H. BUZBY, in his individual capacity; ADOLPH MCQUEEN, in his individual capacity; NELSON CANNON, in his individual capacity; MICHAEL BUMGARNER, in his individual capacity, AKA Mike Bumgarner; WADE DENNIS, in his individual capacity; BRUCE VARGO, in his individual capacity; ESTABAN RODRIGUEZ, in his individual capacity, AKA Stephen Rodriguez, AKA Steve Rodriguez; DANIEL K. MCNEILL, in his individual capacity; GREGORY J. IHDE, in his individual capacity; JOHN DOES 1-100, in their individual capacities; UNITED STATES OF AMERICA, Defendants-Appellees – Cross-Appellants. Appeal from the United States District Court for the Western District of Washington Marsha J. Pechman, Chief District Judge, Presiding Argued and Submitted June 3, 2013—Seattle, Washington HAMAD V. GATES 3 Filed October 7, 2013 Before: Arthur L. Alarcón, M. Margaret McKeown, and Sandra S. Ikuta, Circuit Judges. -

1950 to 2012: the Tradition Continues…

issue 71 spring 2013 THE BULLETIN 1950 TO 2012: The Tradition Continues… See photo captions inside front fold and story p 6 >> issue 71 spring 2013 At the 2012 Annual Meeting at The Waldorf=Astoria in New York City, the College’s Officers, Regents and Past Presidents dined in the Conrad Suite to reenact Emil Gumpert’s 1951 meeting with Fellows in the same room. Sixty-two years and counting: collegiality, combined with the standards of trial practice, the administration of justice and the ethics of the profession remain the hallmarks of the American College of Trial Lawyers. American College of Trial Lawyers 2012 10 21 20 15 16 17 24 14 18 22 23 THE BULLETIN 13 19 12 28 11 27 26 9 25 Chancellor-Founder 8 3 7 31 Hon. Emil Gumpert 6 30 29 (1895-1982) 5 4 OFFICERS Chilton Davis Varner, President 2 Philip J. Kessler, President-Elect 32 Robert L. Byman, Treasurer Francis M. Wikstom, Secretary 33 Thomas H. Tongue, Immediate Past President 1 BOARD OF REGENTS 34 Rodney Acker Dallas, Texas 1. Thomas H. Tongue, President 10. John M. Famularo, Regent 21. Michael F. Kinney, Regent 34. Robert B. Fiske, Jr., Robert L. Byman 2. John J. (Jack) Dalton, 11. Michael M. Cooper, 22. Bartholomew J. Dalton, Regent Past President Chicago, Illinois Past President Past President 23. David J. Hensler, Regent LIVING PAST PRESIDENTS 3. Francis M. Wikstrom, Regent 12. William H. Sandweg, III, Regent 24. David W. Scott, Past President Bartholomew J. Dalton UNABLE TO attend: Wilmington, Delaware 13. Earl J. Silbert, Past President 25. -

Clarion No 801, 01 January 2008 Email Newsletter of Civil Liberties Australia (A04043)

CLArion No 801, 01 January 2008 Email newsletter of Civil Liberties Australia (A04043). E: [email protected] Web: http://www.cla.asn.au/ 2008 is the 60th anniversary of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights Table of Contents High Court asked to broaden NT considerations .......................................................................... 2 CLA plans action on CCC and shield laws ................................................................................... 2 Meetings organized on CLA Senate initiatives ............................................................................. 2 CLA gets ready for active ‘08 ....................................................................................................... 2 Key meetings held, and planned .................................................................................................... 3 100,000 to be sampled annually for DNA; is Australia next? ....................................................... 3 ‘Stunt policing’ is on the nose, QCCL says .................................................................................. 3 Do Not Call register aids people’s privacy .................................................................................... 4 Deaths trigger formal review of stun gun use ............................................................................... 4 Mounties told to restrict stun gun use ............................................................................................ 5 Police accused of firing stun gun into head of innocent -

Advocates for U.S. Torture Prosecutions

Shadow Report to the United Nations Committee Against Torture on the Review of the Periodic Report of the United States of America September 29, 2014 Prepared by Advocates for U.S. Torture Prosecutions Dr. Trudy Bond, Prof. Benjamin Davis, Dr. Curtis F. J. Doebbler, and The International Human Rights Clinic at Harvard Law School Summary: Since the United States last reported to the Committee Against Torture in 2006, even more evidence has emerged confirming that civilian and military officials at the highest level created, designed, authorized, and implemented a sophisticated, international criminal program of torture. In August 2014, President Barack Obama conceded that the United States tortured people as part of its so-called “War on Terror,” yet the United States continues to shield senior officials from liability for these crimes, in violation of its obligations under the Convention Against Torture. Recommended Questions: 1. Why has the United States not prosecuted senior officials for authorizing conduct it admits was torture? 2. Were the following people ever criminally investigated for their role in torture, and why have they not been prosecuted? a. Former President George W. Bush b. Former Office of Legal Counsel (OLC) at the Department of Justice lawyer John Yoo c. Former Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) contractor Dr. James Mitchell Suggested Recommendation: 1. That the United States promptly and impartially prosecute senior military and civilian officials responsible for authorizing, acquiescing, or consenting in any way to acts of torture committed by their subordinates. Advocates for U.S. Torture Prosecutions I. Reporting Organization Advocates for U.S. Torture Prosecutions is a group composed of concerned U.S. -

Table of Contents CHAPTER 18

Table of Contents CHAPTER 18 ................................................................................................................................ 540 Use of Force ............................................................................................................................... 540 A. GENERAL ......................................................................................................................... 540 1. Use of Force Issues Related to Counterterrorism Efforts ................................................ 540 a. President Obama’s speech at the National Defense University .................................. 540 b. Attorney General Holder’s Letter to Congress ............................................................ 546 c. Policy and Procedures for Use of Force in Counterterrorism Operations ................. 549 2. Potential Use of Force in Syria ........................................................................................ 552 3. Bilateral Agreements and Arrangements ......................................................................... 554 a. Implementation of Strategic Framework Agreement with Iraq ................................... 554 b. Protocol to the Guam International Agreement ........................................................... 556 4. International Humanitarian Law ...................................................................................... 556 a. Protection of civilians in armed conflict ..................................................................... -

War Courts: Terror's Distorting Effects on Federal Courts Collin P

Legislation and Policy Brief Volume 3 | Issue 1 Article 1 1-6-2011 War Courts: Terror's Distorting Effects on Federal Courts Collin P. Wedel Stanford University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.wcl.american.edu/lpb Part of the Courts Commons, and the Military, War and Peace Commons Recommended Citation Wedel, Collin P. (2011) "War Courts: Terror's Distorting Effects on Federal Courts," Legislation and Policy Brief: Vol. 3: Iss. 1, Article 1. Available at: http://digitalcommons.wcl.american.edu/lpb/vol3/iss1/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Washington College of Law Journals & Law Reviews at Digital Commons @ American University Washington College of Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Legislation and Policy Brief by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ American University Washington College of Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 7 WAR COURTS: TERROR’S DISTORTING EFFECTS ON FEDERAL COURTS Collin P. Wedel* Preface ................................................................................................7 I. Introduction ............................................................................9 II. Habeas Corpus and the Suspension Clause ..................14 III. Military Detention and Criminal Incarceration .....21 IV. Criminal Procedure .............................................................29 A. Miranda Protections .............................................29 B. tribunal Procedures in Federal courts ..................33 V. Conclusion .............................................................................37 Preface In recent years, federal courts have tried an increasing number of sus- pected terrorists. In fact, since 2001, federal courts have convicted over 403 people for terrorism-related crimes.1 Although much has been written about the normative question of where terrorists should be tried, scant research exists about the impact these recent trials have had upon the Article III court system.