Aalborg Universitet ESCO in Danish Municipalities: Basic, Integrative Or

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ravn, Troels (S)

Ravn, Troels (S) Member of the Folketing, The Social Democratic Party Primary school principal Dalgårdsvej 124 6600 Vejen Mobile phone: +45 6162 4783 Email: [email protected] Troels Ravn, born August 2nd 1961 in Bryrup, son of insurance agent Svend Ravn and housewife Anne Lise Ravn. Married to Gitte Heise Ravn. Member period Member of the Folketing for The Social Democratic Party in South Jutland greater constituency from January 12th 2016. Member of the Folketing for The Social Democratic Party in South Jutland greater constituency, 15. September 2011 – 18. June 2015. Member of the Folketing for The Social Democratic Party in Ribe County constituency, 8. February 2005 – 13. November 2007. Temporary Member of the Folketing for The Social Democratic Party in South Jutland greater constituency (substitute for Lise von Seelen), 29. October 2008 – 20. November 2008. Candidate for The Social Democratic Party in Vejen nomination district from 2007. Candidate for The Social Democratic Party in Grindsted nomination district, 20032007. Parliamentary career Spokesman on fiscal affairs from 2019. Supervisor of the Library of the Danish Parliament from 2019. Chairman of the Social Affairs Committee, 20162019. Chairman of the South Schleswig Committee, 20142015. Spokesman on cultural affairs and media, 20142015. Chairman of the Immigration and Integration Affairs Committee, 20132015. Supervisor of the Library of the Danish Parliament, 20112015. Spokesman on children and education, 20112014. Member of the Children's and Education Committee, of the Cultural Affairs Committee, of the Gender Equality Committee and of the Rural Districts and Islands Committee, 20112015. Vicechairman of the Science and Technology Committee, 2007. -

Open Call Kolding Den 14

Open Call Kolding den 14. november 2017 Art projects for the Triangle Festival 2019 From 23 august to 1 September 2019 For the last couple of years, art has played a bigger and bigger role in the Triangle Festival. We would like to do even more to visualize the art experiences in our festival and make them more accessible to our audience. Therefore, we have chosen to show art in seven Art Zones. Each Art Zone has its own aesthetics and history - places where people meet, hang out or pass by. The seven art zones have different hosts, and they will each get different expressions that appeal to different people. We are looking for art projects that work site-specific and who will explore the festival theme ’MOVE’. We wish that some of the projects involve the audience, but it is not a requirement for all projects. The Seven Art Zones The Manor House Sønderskov offers a special aesthetic experience with historical depth. The beautiful frames invite art projects that awaken curiosity. The Town Square ’Gravene’ The square is located in the part of Haderslev, which houses the oldest central districts near Haderslev Cathedral. The place is full of history and invites to art projects that experiment with the possibilities of the place. The Library Park The place is a recreational city oasis for the citizens. It has been created each year since 2016 in front of Kolding Library for a few weeks in late summer. Invites projects that surprise and experiment with creating new rooms in the city. The Mental Hospital (Teglgårdsparken) The former mental hospital in the city of Middelfart invites to a cultural day focused on psychiatry in fascinating historical frameworks. -

August 25Th - September 3Rd, 2017

Welcome to the Triangle Region Festival: August 25th - September 3rd, 2017 Once again, The Triangle Region brings you a spectacular festival program that challenges, moves and entertains. Get ready to immerse yourself in music, theatre, art, dance, lectures and children’s culture. The Triangle Region’s many beautiful buildings, squares, nature areas and historic sites will be the platform for the events – inspiring new connections and ways of expression. So come and join us as we unleash culture and creativity in Billund, Fredericia, Haderslev, Kolding, Middelfart, Vejen and Vejle. It can only happen here! Program Billund Municipality We take reservations for typographical errors and programme changes. FRIDAY, AUGUST 25 WEDNESDAY, AUGUST 30 14:00-22:00 Campus Festival. MAGION, Campustorvet, Grindsted 09:30 Asphalt dance party for schools and after-school programs – children’s concert. 14:00-22:00 International Children’s Culture Days. Colourful festival with emphasis on play, Festival Tent, Nørretorv, Grindsted learning, creativity and the intersection of cultures. Billund Centret (Billund Community Centre) 16:00 Carsten Dahl art exhibition. Billund Centret (Billund Community Centre) 14:00-22:00 Street Piano. Come play and dance. Billund Centret (Billund Community Centre. 19:00 Carsten Dahl solo piano concert. Billund Church 13:00-16:00 Making Waves. Workshop. Billund Centret (Billund Community Centre) 19:30 Mike Tramp concert. The Festival Tent, Nørretorv, Grindsted SATURDAY, AUGUST 26 THURSDAY, AUGUST 31 10:00-22:00 International Children’s Culture Days. Colourful festival with emphasis on play, 17:00 Bike’n’Run Relay. The Festival Tent, Nørretorv, Grindsted learning, creativity and the intersection of cultures. -

Geographical Variation in Antipsychotic Drug Use in Elderly Patients with Dementia: a Nationwide Study

Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease 54 (2016) 1183–1192 1183 DOI 10.3233/JAD-160485 IOS Press Geographical Variation in Antipsychotic Drug Use in Elderly Patients with Dementia: A Nationwide Study Johanne Købstrup Zakariasa,b, Christina Jensen-Dahma, Ane Nørgaarda, Lea Stevnsborga, Christiane Gassec, Bodil Gramkow Andersend, Søren Jakobsene, Frans Boch Waldorfff , Torben Moosb and Gunhild Waldemara,∗ aDanish Dementia Research Centre, Department of Neurology, Rigshospitalet, University of Copenhagen, Copenhagen, Denmark bLaboratory of Neurobiology, Biomedicine Group, Department of Health Science and Technology, Aalborg University, Aalborg, Denmark cNational Centre for Register Based Research, Aarhus University, Aarhus, Denmark dDepartment of Clinical Medicine, Aalborg University Hospital, Aalborg, Denmark eDepartment of Geriatric Medicine, Odense University Hospital, Svendborg, Denmark f Research Unit for General Practice, Department of Public Health, University of Southern Denmark, Odense, Denmark Accepted 28 June 2016 Abstract. Background: Use of antipsychotics in elderly patients with dementia has decreased in the past decade due to safety regulations; however use is still high. Geographical variation may indicate discrepancies in clinical practice and lack of adherence to evidence-based guidelines for the management of behavioral symptoms. Objective: To investigate potential geographical variances in use of antipsychotic drugs in dementia care. Methods: A registry-based cross-sectional study in the entire elderly population of Denmark (≥65 years) conducted in 2012. Data included place of residence, prescriptions filled, and hospital discharge diagnoses. Antipsychotic drug use among elderly with (n = 34,536) and without (n = 931,203) a dementia diagnosis was compared across the five regions and 98 municipalities in Denmark, adjusted for age and sex. Results: In 2012, the national prevalence of antipsychotic drug use was 20.7% for elderly patients with dementia, with a national incidence of 3.9%. -

Download 3,3 MB

29 By, marsk og geest 29 Kulturhistorisk tidsskrift for Sydvestjylland Forlaget Liljebjerget 2017 By, marsk og geest er fagfællebedømt i henhold til Forsknings- og Innovationsstyrelsens retningslinier. Indhold Redaktion: Mette Højmark Søvsø, Bo Ejstrud, Flemming Just, Martin Egelund Poulsen Claus Feveile, Morten Søvsø. Bebyggelse og landbrug i overgangsperioden mellem yngre stenalder og ældre bronzealder – betragtninger fra et sydjysk indlandsområde ..................... s. 05 Layout: KIRK & HOLM Settlement and agriculture in the transition of the Late Neolithic and Early Bronze Age Tryk: Rosendahls – observations from a southern Jutland inland region ............................................................................... s. 29 Copyright: 2017 Forlaget Liljebjerget Lars Grundvad og Maria Knudsen Liljebjerget er Sydvestjyske Museers forlag. Det blev oprettet i 1997 til minde om Fæstedskatten – dynastisk guldsmedekunst og med testamentariske midler fra Ellen og Christian Almhede. i 900-årenes Danmark .............................................................. s. 30 The Fæsted hoard – Dynastic goldsmith Forlagets navn rækker tilbage til Anders Sørensen Vedel. Han udgav i årene production from 10th century Denmark ................................. s. 49 1591–92 otte bøger, der var „Prentet paa Liliebierget udi Ribe“. Om disse bogudgivelser og trykkeriet se By, marsk og geest 10, 1998. Claus Feveile ISBN 978-87-89827-63-5 Ombukkede knivskedebeslag af blik ...................................... s. 50 Folded scabbard chapes of sheet -

Vejen Offers a Peaceful Fa- Mily Life for Those Who Love Nature, Space and History

COME AND MEET OUR NEWCOMER GUIDES IN THE TRIANGLE REGION. IN THIS ISSUE: VEJEN Vejen offers a peaceful fa- mily life for those who love nature, space and history HANNA KRETZSCHMAR VEJEN MUNICIPALITY Vejen Municipality is a great place to live if you want a peaceful, safe and not too hectic life for your family. Its small communiti- es make it easy to connect with people and if you enjoy getting out in the nature, there are plenty of opportunities for fresh air. In Vejen Municipality you are never too far away from water and forests in your daily life. There are many sporting and cultural activities available which Many companies in the agricultural sector are located in this are run by the local associations (foreninger). This is a very po- region and a great number of jobs are waiting for newcomers pular Danish way to enjoy your hobbies and make new friends. on farms and in food production – providing a stable backg- Hanna Kretzschmar, the newcomer guide in Vejen Munici- round to help families to settle in. pality, fell in love with the history of the region: the beautiful surroundings of the river Kongeåen; the Ancient Road Hærve- Well-established support system for newcomers in Vejen jen (which offers fantastic hiking and biking experiences); the Municipality oldest high school in Denmark and several other monuments “I was born and raised in Denmark, but I have lived in different that remind her about the power of a community thinking and areas. From the island of Fyn we moved to the very tight-knit working together. -

Smart Cities Citizen Innovation in Smart Cities Final Application (Excerpt) Project Final Application (Excerpt)

Smart Cities Citizen Innovation in Smart Cities Final Application (excerpt) Project Final Application (excerpt) URBACT II SMART CITIES Citizen Innovation in Smart Cities Lead Partner City of Coimbra Project Coordinator Fernando Zeferino Ferreira Finance Officer Rosa Silva Communication officer Nina Figueiredo Lead Expert Peter Ramsden Websites www.urbact.eu http://urbact.eu/en/projects/innovation-creativity/smart-cities/homepage/ Logo design Mónica Sousa Photography and graphic design (on URBACT template) Fernando Zeferino Ferreira 1. Project Identity Project Title, Lead Partner and Duration Smart Cities – Citizen Innovation in Smart Cities The Lead Partner is the City of Coimbra (PT). The project has two phases: Development phase ( 6 months) and Implementation phase (27 months) Update summarised description of project and issue addressed In the summarized description for the DOI Application form, is stated that the main objective of the SMART CITIES Project is to develop a different picture of how public services could be organized through an open innovation process, considering the citizens in the core of system, to help the local authorities in creating new tools for improving the quality of life and well-being of communities and citizens. The project intends to foster Smart Cities (and communities) that promotes social innovation and inclusiveness together with economic innovation and environmental sustainability, in line with the EU Strategy 2020. The Smart cities network is to develop a new relationship between municipalities and their citizens. This new approach is based on citizen or user led innovation and aims to rebuild trust and create shared models of delivery. This new relationship will be developed through two parallel approaches, one focusing on particular areas of the city which is called Smart localities, the other on horizontal policies called Smart services. -

Contacts in the Region of Southern Denmark Organisation Name Title

Contacts in the Region of Southern Denmark Organisation Name Title Email Phone number Aabenraa Municipality Eva-Christine Aaen Damsleth Larsen Settlement Coordinator [email protected] 20347382 Aabenraa Municipality Julia Schatte Business Consultant [email protected] 51502869 Aabenraa Municipality Louise Davids Settlement Coordinator [email protected] 53631166 Aabenraa Municipality Maria Heesch Recruitment Manager [email protected] 23441465 The Development Council of Southern Denmark Tina Hansen Petersen Project Manager [email protected] 40343666 KompetenceCenter Billund Antje Niklas International Recruiting Consultant [email protected] 20168826 Nyborg Municipality Betina Østergreen Head of citizen service centre [email protected] 51199080 Nyborg Municipality Pia Andersen Citizen counsellor/Case officer [email protected] 63337977 Odense Municipality Nikolaj Knude Hansen Consultant [email protected] 30713287 Sønderborg Municipality Newcomer Service Tatjana Marika Rode Settlement Coordinator [email protected] 27907468 Work-Live-Stay Camilla Høholt Smith General Manager [email protected] KompetenceCenter Billund Raluca Lucacel International Recruitment Consultant [email protected] 21502853 Haderslev Municipality Anita Müller Tjørnelund Settlement Coordinator [email protected] 74340361 Odense Municipality Aleksandra Jensen Spouse Consultant [email protected] 51464238 Tønder Trade Council Amit Mozumdar Business Consultant [email protected] 20313977 The Triangle Region Karen Margrethe Kyhl Winther Development Consultant [email protected] 30580410 Middelfart -

Facts and Figures of the Wadden Sea Region

Facts and Figures of the Wadden Sea Region Part I of the Baseline Study for the Strategy for Sustainable Tourism in the Wadden Sea June 2012 Prepared by Wadden Sea Baseline Study Part 1: Facts and Figures page 2 Wadden Sea Baseline Study Part 1: Facts and Figures page 3 Contents Background ............................................................................................................................................ 5 1 Basic data on tourism .................................................................................................................. 7 1.1 German Wadden Sea region ...................................................................................................... 7 1.1.1 Number and types of accommodation ............................................................................... 7 1.1.2 Number of overnight stays in Schleswig-Holstein and Lower Saxony ............................ 10 1.1.3 Number of day visitors ..................................................................................................... 14 1.2 Danish Wadden Sea region ..................................................................................................... 15 1.2.1 Number and types of accommodation ............................................................................. 15 1.2.2 Number of overnight stays ............................................................................................... 15 1.2.3 Day-visitors ..................................................................................................................... -

International Conference a B S T R a C

International conference Restoration of Streams with special emphasis on the houting and the Houting Project 3-5 October 2011, Tønder, Denmark A B S T R A C T S Fish Farm Bramming in the River Sneum system after restoration (July 2011))) 2 Monday 1530-1650 - Session I A short history of stream restoration in Denmark.................................................................. 4 Criteria for assessment of stream continuity ......................................................................... 5 Genetic monitoring of the endangered North Sea houting (Coregonus oxyrhinchus) ........... 6 River restoration of Nørresø in the Vidå system ................................................................... 7 Tuesday 1005-1145 - Session II Simulating the migration of Houting larvae in a constructed wetland using Agent Based Modeling (ABM) and hydro-dynamical modeling ....................................................... 8 The houting population of the River Treene: Hydromorphology, fish biological status and restoration measures ..................................................................................................... 9 The houting population of the Treene River (Northern Germany): Genetics, resource use and population dynamics ............................................................................................. 10 In the Search for the North Sea Houting – a study of mitogenomics in the European lake whitefish and the North Sea Houting........................................................................... 11 Do -

Mapping of Textile Flows in Denmark

Mapping of textile flows in Denmark Environmental Project No. 2025 August 2018 Publisher: The Danish Environmental Protection Agency Authors: David Watson, PlanMiljø Steffen Trzepacz, PlanMiljø Ole Gravgård Pedersen, Danmarks Statistik ISBN: 978-87-93710-48-1 The Danish Environmental Protection Agency publishes reports and papers about research and development projects within the environmental sector, financed by the Agency. The contents of this publication do not necessarily represent the official views of the Danish Environmental Protection Agency. By publishing this report, the Danish Environmental Protection Agency expresses that the content represents an important contribution to the related discourse on Danish environmental policy. Sources must be acknowledged. 2 The Danish Environmental Protection Agency / Mapping of textile flows in Denmark Contents Summary 4 1 Background 8 2 Project objectives and outputs 10 3 Method for data collection and analysis 11 3.1 General principles 11 3.2 Stage 1: Calculations of total supply of textiles to Denmark 12 3.3 Stage 2: Calculations of Overall Split in Consumption by Sector 13 3.4 Stage 3: Mapping flows of used textiles from households 15 3.5 Stage 4: Mapping flows of used textiles from business and government or- ganisations 22 3.6 Stage 5: The value of textiles in mixed waste 24 4 Results: Textile Flows in Denmark 27 4.1 Overall supply of new textiles 27 4.2 Flows of used textiles from households 29 4.3 Flows of used textiles from the public sector and businesses 46 5 The lost value of textiles -

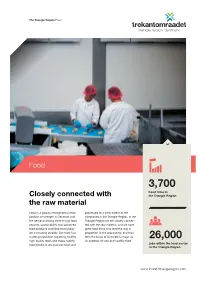

Closely Connected with the Raw Material

The Triangle Region Food Food 3,700 Food firms in Closely connected with the Triangle Region the raw material Food is a globally recognised Danish processed to a great extent at the position of strength in Denmark and companies in the Triangle Region. In the the demand among other things food Triangle Region we are closely connec- security, sustainability and advanced ted with the raw material, and we have food products and food technology great food firms who lead the way in are increasing steadily. Denmark has proportion to the processing, and they a strong reputation regarding healthy form the basis of Denmark’s image as 26,000 high-quality food, and these healthy an exporter of safe and healthy food. food products are manufactured and jobs within the food sector in the Triangle Region www.investintriangleregion.com The Triangle Region Food The Triangle Region has a strong capability within the field of food products In the Triangle Region the ecosystem are registered in the Triangle Region. for food products is conspicuous. In The area indeed counts several large Vejen Municipality there is a national and globally-oriented food firms such position of strength within food pro- as Carlsberg, Easy Foods, Skare Meat duction and safety. In Vejle Municipali- Packers K/S, Danæg, Arla Danish ty they are adding another layer to the Crown, Tulip, Danpo and others. The Triangle skilled business talent within the field Eurofin’s European headquarters for of food products with the new Food lab tests/food safety is also located Region is an Innovation House which is a position in Vejen Municipality and is one of the important factor of strength here.