Pre-Feasibility Study of Sarawak-West Kalimantan Cross-Border Value Chains

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hydropower Development and Community Transformation in Sarawak Sharbini Suhaili Group Chief Executive Officer Sarawak Energy Berhad About Sarawak Energy

The 13th World Islamic Economic Forum ‘Disruptive Change: Impact and Challenges’ Hydropower Development and Community Transformation in Sarawak Sharbini Suhaili Group Chief Executive Officer Sarawak Energy Berhad About Sarawak Energy • Fully integrated power utility and energy development company, wholly owned by the state of Sarawak • Generates power through hydro and thermal (coal and gas) • Serving a population of 2.6 million covering 650,000 domestic, commercial, industrial and export customers through an extensive transmission and distribution network. • Multidisciplinary workforce of 5,000 • Lowest tariffs in Malaysia and amongst the lowest in South East Asia 2 Holistic View of Energy Development • Balanced energy development • drives socio economic transformation • requires energy reliability, sustainability and affordability • Sarawak Energy is focused on • A balanced generation mix for energy reliability and security • Affordability, we offer amongst the lowest tariff in the region, through hydropower development • Sustainability - 75% renewable hydro energy, guided by the international best practices such as IHA Sustainability Assessment Protocol 3 Expected Demand - Supply Scenario 1985 – 2035 Today (4,652MW) 4 Generation Mix and Installed Capacity 15 0.7% .7% 16 • Predominantly renewable hydropower 0.9% • Balance of thermal to maintain diversity and .4% 20 security of supply 13 67 .7% 2025 .8% .2% 7,048MW 64 10 0.2 2.5 .6% .3% %12 % 2020 .8% 74 5,341MW .2% 130.9 13 2016 Generation Type .8…% .1… 4,652MW Hydro Coal Gas 12 2000 -

Heart of Borneo, a Joint Commitment Rn Conserve, Protect Diverse World

Heartof Borneo,a jointcommitment rn diverse State has balls. To date, The bungalow ecosystembiological diver- It be denied that the Since early this year, NREB The Park 750 old governmentworld conservation of cannot conserve,government protect using reef (including taken initiatives to identify reef balls have been deployed at Santubong, where Wallace sity trans boundary people do steal timber; hence con- has been implementing the Biodiversity Conservation and gazette several tracts within the area. wrote the famous "The Sarawak Area tinuous efforts have been made Environmental Audit process to further of natural forests, consisting of The project also includes base- Law"; a preamble to the Theory networks), community-based to strengthen supervisory and strengthen the environ- national parks, wildlife sanctuar- line studies on marine and coastal of Evolution, and Rajah's retreat rural poverty eradication and ragging powers by putting all the mental initiatives and, at the same based ies and nature reserves, as totally resources, communication, edu- at Mount ecotourism on Culture, departments together so that sur- time, encourage the develop- Adventure Nature (CAN). Self- protected areas (TPAs) with the cation and public awareness pro- Serambu will be developed and veillance and prevention can be ment sectors to advocate The State target of one million hectares by grammes. to attract visiting scientists and government encour- more effective. Regulation to ensure better com- 2020. More tukun as fishery sanctuar- tourists. ages all forest timber licensees It might not be 100% effective, pliance to Terms and Approval Up to now, 47 TPAs, with a total ies will be built along the Sarawak Tan Sri Adenan says Brunei within the Heart of Borneo areas but efforts are being made to get Environmental Conditions area of 808,100 hectares, have coast land to conserve national Darussalam, Indonesia and to be certified under the Malaysian as effective as possible. -

The BIMP-EAGA Port Booklet

The BIMP-EAGA Port Booklet Published with support from the Asian Development Bank (ADB) Regional Policy Advocay technical Assistance (R-PATA) on support for Trade Facilitation in BIMP-EAGA The BIMP-EAGA Port Booklet Published with support from the Asian Development Bank (ADB) Regional Policy Advocay technical Assistance (R-PATA) on support for Trade Facilitation in BIMP-EAGA Contents BRUNEI DARUSSALAM Port of Muara 6 INDONESIA Port of Balikpapan 10 Port of Bitung 12 Port of Nunukan 14 Port of Pontianak 16 Port of Tarakan 18 MALAYSIA Port of Kuchin 22 Port of Kudat 24 Port of Labuan 26 Port of Miri 28 Port of Sandakan 30 Port of Tawau 32 2 PHILIPPINES Port of Bongao 36 Port of Brooke’s Point 38 Port of Dapitan 40 Port of Glan 42 Port of Pagadian 42 3 Brunei Darussalam Brunei Darussalam Brunei Darussalam Brunei Darussalam Port of Muara 1. Location Muara Port is the main international gateway for Brunei Darussalam. It is located on the and Layout island of Borneo and at located Lat 5 0’ 52” N Long 115 4’ 1”E. Muara Port was opened for commercial operations in February 1973, and commissioned as the Ports Department on 1st. May 1974. The Ports Department of Brunei (established in January 1986) is tasked with the management and operations of the Port. Muara port is served by numerous shipping lines connecting it to the regional hub ports including Kota Kinabalu, Kuching, Penang, Port Klang, Tanjung Pelepas and Singapore. 2. City Hinterland Brunei Darussalam and both Sabah and Sarawak 3. Main Cargo Both Containerized and conventional cargoes are handled at the port. -

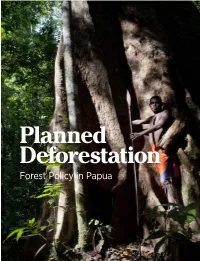

Planned Deforestation: Forest Policy in Papua | 1

PLANNED DEFORESTATION: FOREST POLICY IN PAPUA | 1 Planned Deforestation Forest Policy in Papua PLANNED DEFORESTATION: FOREST POLICY IN PAPUA | 3 CITATION: Koalisi Indonesia Memantau. 2021. Planned Deforestation: Forest Policy in Papua. February, 2021. Jakarta, Indonesia. Dalam Bahasa Indonesia: Koalisi Indonesia Memantau. 2021. Menatap ke Timur: Deforestasi dan Pelepasan Kawasan Hutan di Tanah Papua. Februari, 2021. Jakarta, Indonesia. Photo cover: Ulet Ifansasti/Greenpeace PLANNED DEFORESTATION: FOREST POLICY IN PAPUA | 3 1. INDONESIAN DEFORESTATION: TARGETING FOREST-RICH PROVINCES Deforestation, or loss of forest cover, has fallen in Indonesia in recent years. Consequently, Indonesia has received awards from the international community, deeming the country to have met its global emissions reduction commitments. The Norwegian Government, in line with the Norway – Indonesia Letter of Intent signed during the Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono presidency, paid USD 56 million,1 equivalent to IDR 812 billion, that recognizes Indonesia’s emissions achievements.2 Shortly after that, the Green Climate Fund, a funding facility established by the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), agreed to a funding proposal submitted by Indonesia for USD 103.8 million3, equivalent to IDR 1.46 trillion, that supports further reducing deforestation. 923,050 923,550 782,239 713,827 697,085 639,760 511,319 553,954 508,283 494,428 485,494 461,387 460,397 422,931 386,328 365,552 231,577 231,577 176,568 184,560 2001 2003 2005 2007 2009 2011 2013 2015 2017 2019 Figure 1. Annual deforestation in Indonesia from 2001-2019 (in hectares). Deforestation data was obtained by combining the Global Forest Change dataset from the University of Maryland’s Global Land Analysis and Discovery (GLAD) and land cover maps from the Ministry of Environment and Forestry (MoEF). -

Customs-Business Partnerships

No 61 FEBRUARY 2010 W CONEWS www.wcoomd.org Customs-Business Partnerships: Customs - Business Partnership combiningPartenariat Douane - Entreprisesour talents! ena part rIat WCO Data Model: CoopérationWCO data MOdel Innovation cross-border transactions on the fast track facilitation receives a boost s e s D ORGANISATION MONDIALE DES DOUANES I o r u p a e n r e t n CENcomm:e anticipationoperational data exchange optimized Conjuguons nos talents pour être plus performants! World Customs Organization f l a s h i N f O 2 WCO News – No 61 – February 2010 Customs - Business Partnership Partenariat Douane - Entreprises Content WCOW NE s n° 61 February 2010 4 Calendar 36 In conversation • Mr. Jean Rozwadowski, Secretary General of the 5 Editorial International Chamber of Commerce • Mr. Thomas Schoeneck, Chairperson of the WCO Finance 6 Buzz Committee 9 Flash Info 41 Our Members world 15 Special Dossier 47 Zoom • Information, consultation and cooperation; the main • Tunisia's General Directorate of Customs ingredients of the WCO-Trade partnership • TAXUD talks business 48 Point of View • Customs and business: partners in fighting illegal • The success story of the Montreal Protocol on Substances movements of hazardous waste that Deplete the Ozone Layer • Focusing Customs on client service • The role of the private sector in trade facilitation 51 Events • UNEP’s Public-Private Partnership strengthens Customs’ • Fifth Global Congress on Combating Counterfeiting and environment protection role Piracy, Cancun (Mexico) • Mozambique maximizes revenue -

IN TAX LEADERS WOMEN in TAX LEADERS | 4 AMERICAS Latin America

WOMEN IN TAX LEADERS THECOMPREHENSIVEGUIDE TO THE WORLD’S LEADING FEMALE TAX ADVISERS SIXTH EDITION IN ASSOCIATION WITH PUBLISHED BY WWW.INTERNATIONALTAXREVIEW.COM Contents 2 Introduction and methodology 8 Bouverie Street, London EC4Y 8AX, UK AMERICAS Tel: +44 20 7779 8308 4 Latin America: 30 Costa Rica Fax: +44 20 7779 8500 regional interview 30 Curaçao 8 United States: 30 Guatemala Editor, World Tax and World TP regional interview 30 Honduras Jonathan Moore 19 Argentina 31 Mexico Researchers 20 Brazil 31 Panama Lovy Mazodila 24 Canada 31 Peru Annabelle Thorpe 29 Chile 32 United States Jason Howard 30 Colombia 41 Venezuela Production editor ASIA-PACIFIC João Fernandes 43 Asia-Pacific: regional 58 Malaysia interview 59 New Zealand Business development team 52 Australia 60 Philippines Margaret Varela-Christie 53 Cambodia 61 Singapore Raquel Ipo 54 China 61 South Korea Managing director, LMG Research 55 Hong Kong SAR 62 Taiwan Tom St. Denis 56 India 62 Thailand 58 Indonesia 62 Vietnam © Euromoney Trading Limited, 2020. The copyright of all 58 Japan editorial matter appearing in this Review is reserved by the publisher. EUROPE, MIDDLE EAST & AFRICA 64 Africa: regional 101 Lithuania No matter contained herein may be reproduced, duplicated interview 101 Luxembourg or copied by any means without the prior consent of the 68 Central Europe: 102 Malta: Q&A holder of the copyright, requests for which should be regional interview 105 Malta addressed to the publisher. Although Euromoney Trading 72 Northern & 107 Netherlands Limited has made every effort to ensure the accuracy of this Southern Europe: 110 Norway publication, neither it nor any contributor can accept any regional interview 111 Poland legal responsibility whatsoever for consequences that may 86 Austria 112 Portugal arise from errors or omissions, or any opinions or advice 87 Belgium 115 Qatar given. -

Gonadotropin-Releasing Hormone

Induced breeding in tropical fish culture Induced breeding in tropical fish culture Brian Harvey and J. Carolsfeld with a foreword by Edward M. Donaldson INTERNATIONAL DEVELOPMENT RESEARCH CENTRE Ottawa • Cairo • Dakar • Johannesburg • Montevideo • Nairobi New Delhi • Singapore ©International Development Research Centre 1993 PO Box 8500, Ottawa, Ontario, Canada KlG 3H9 Harvey, B. Carolsfeld, J. Induced breeding in tropical fish culture. Ottawa, Ont., IDRC, 1993. x + 144 p. : m. /Fish culture/, /fish breeding/, /endocrine system/, /reproduction/, /artificial procreation/, /salt water fish/, /freshwater fish/, /tropical zone/-/hormones/, /genetic engineering/, /genetic resources/, /resourcès conservation/, /environmental management/, /fishery management/, bibliographies. UDC: 639.3 ISBN: 0-88936-633-0 Technical editor: G.C.R. Croome A microfiche edition is available. The views expressed in this publication are th ose of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of the International Development Research Centre. Mention of a proprietary name does not constitute endorsement of the product and is given only for information. Abstract-The book summarizes current knowl edge of the reproductive endocrinology of fish, and applies this knowledge to a practical end: manipulation of reproduction in captive fish that are grown for food. The book is written in a deliberately "nonacademic" style and covers a wide range of topics including breed ing, manipulation of the environment to induce breed ing, conservation offish genetic resources, and techniques used for marking and tagging broodstock. Résumé - L'ouvrage fait le point des connaissances actuelles en matière d'endocrinologie de la reproduction du poisson dans le souci d'une application bien concrète : la manipulation de cette fonction pour les besoins de la pisciculture. -

Concern of Veterinary Authorities with Respect to Borders Crossing

Concern of Veterinary Authorities With Respect to Borders Crossing NURUL HUSNA ZULKIFLI DEPARTMENT OF VETERINARY SERVICES MALAYSIA 19 FEBRUARY 2019 DEPARTMENT OF VETERINARY SERVICES MALAYSIA 01 Overview Under the Ministry of Agriculture and Agro-Based Industries (MOA) Malaysia 02 Responsibility Veterinary competent authority of Malaysia 03 Scope Responsible in performing risk analysis as well as development of import requirements and for issuance of veterinary health certificate (as stated under the Provisions of Animals Act 1953, Section 16. DEPARTMENT OF QUARANTINE & INSPECTION SERVICES MALAYSIA (MAQIS) 01 Overview Under the Ministry of Agriculture and Agro-Based Industries (MOA) Malaysia 02 Responsibility One stop centre for quarantine and inspection services 03 Scope Responsible in the enforcement of written laws at entry point, quarantine stations and quarantine premises as well as in the issuance of permits, licenses and certificates of import and export DVS as a competent authority responsible in the approval of animal and animal products movement STATE DVS IN MALAYSIA 1. Perlis 2. Kedah 3. Pulau Pinang 4. Kelantan 5. Terengganu 6. Perak 7. Pahang 8. Selangor 9. Putrajaya (Headquarters) 10. Negeri Sembilan 11. Melaka 12. Johor 13. Labuan MAQIS as main agency responsible in quarantine, inspection and enforcement STATE MAQIS IN MALAYSIA 1. Selangor/Negeri Sembilan 2. Johor/Melaka 3. Pulau Pinang 4. Kedah 5. Kelantan 6. Perlis 7. Perak 8. Labuan 9. Pahang/Terengganu MAQIS Quarantine Station Labuan KLIA • KLIA Quarantine Station • Padang -

INAGAKI, Kazuya, 2020. 'Word Stress in Pontianak Malay'. in Thomas J. CONNERS and Atsuko UTSUMI, Eds. Aspects of Regional Va

Word stress in Pontianak Malay Kazuya INAGAKI Nanzan University The aim of this paper is to describe word stress in Pontianak Malay from an impressionistic viewpoint, with supportive evidence from both acoustic analysis and (morpho-) phonological data. No research has been done on word stress in Pontianak Malay to date. I argue that this language has fixed (non-distinctive) ultimate word stress which only bears delimitative function. The main prosodic features for determining word stress in Pontianak Malay are length and clearness of vowels. This paper looks into the realization of these prosodic features through examining target words and presents supportive evidence for a descriptive generalization of word stress in Pontianak Malay. 1. Overview1 Pontianak Malay (hereafter PoM) is a vernacular variety of Malay spoken in and around the city of Pontianak, West Kalimantan province, Indonesia. Ethnoloɠue estimates the total number of speakers for three Malay varieties, i.e., Pontianak/Sambas/Ketapang Malay spoken in West Kalimantan as 940,000 (Simons & Fennig 2018: 186). Southeast Asia began an age of trading and religious activity around the 15th century. From the 18th century, Arab migrants, including Hadhrami Arabs from Yemen, began to reside increasingly in West Kalimantan. Additionally, Pontianak became a main trade center of West Kalimantan in the 18th century, attracting Buginese and southern Chinese people to come and work there, primarily in plantation and gold mining. In addition to immigrants from Java and South Sulawesi, Madurese also came to the Pontianak region under the transmigration program in the late 20th century. Currently Pontianak is composed of different ethnic groups, including Arabic, Chinese, Javanese, Buginese, Madurese, as well as the native ethnic groups of Malay and Dayak. -

Kabupaten Dalam Angka Bengkayang 2021

KABUPATEN BENGKAYANG DALAM ANGKA 2021 https://bengkayangkab.bps.go.id BADAN PUSAT STATISTIK KABUPATEN BENGKAYANG BPS-Statistics of Bengkayang Regency KABUPATEN BENGKAYANG DALAM ANGKA 2021 https://bengkayangkab.bps.go.id KABUPATEN BENGKAYANG DALAM ANGKA Bengkayang Regency in Figures 2021 ISSN: 2540-850X No. Publikasi/Publication Number: 61020.2101 Katalog /Catalog: 1102001.6102 Ukuran Buku/Book Size: 14,8 cm x 21 cm Jumlah Halaman/Number of Pages : xxxvi + 250 hal/pages Naskah/Manuscript: BPS Kabupaten Bengkayang BPS-Statistics of Bengkayang Regency Penyunting/Editor: BPS Kabupaten Bengkayang BPS-Statistics of Bengkayang Regency Desain Kover/Cover Design: Fungsi Integrasi Pengolahan dan Diseminasi Statistik Functionhttps://bengkayangkab.bps.go.id of Integration Processing and Statistics Dissemination Ilustrasi Kover/Cover Illustration: Tarian Tradisional Dayak/Dayak Traditional Dance Diterbitkan oleh/Published by: ©BPS Kabupaten Bengkayang/BPS-Statistics of Bengkayang Regency Dicetak oleh/Printed by: Badan Pusat Statistik Dilarang mengumumkan, mendistribusikan, mengomunikasikan, dan/atau menggandakan sebagian atau seluruh isi buku ini untuk tujuan komersil tanpa izin tertulis dari Badan Pusat Statistik. Prohibited to announce, distribute, communicate, and/or copy part or all of this book for commercial purpose without permission from BPS-Statistics Indonesia. TIM PENYUSUN / DRAFTING TEAM Penanggungjawab Umum/General in Charge: Amad Badar, SE, MM Penanggungjawab Publikasi/Publication General in Charge: Ilham Mauluddin,S.ST Pemeriksaan -

Reconciling Economic Growth with Emissions Reductions

In cooperation with: Financial Cooperation (KfW) This module focuses on the implementation of REDD+ ‘on the ground’. It aims to demonstrate the viability of a pro-poor REDD mechanism in Kalimantan to decision-makers and stakeholders, is the German Development Bank, thus enriching the national and international debate on REDD+ acting on behalf of the German Government. It with practical implementation experience. KfW uses a district carries out cooperation projects with developing based approach in order to prepare selected pilot areas for national and emerging countries. In Indonesia, KfW’s and international carbon markets. KfW finances measures to long-standing cooperation started in 1962 with achieve readiness in three districts of Kalimantan (Kapuas Hulu, its local office in Jakarta established in 1998. KfW Malinau, Berau), realizes an investment programme for REDD has been actively engaged in the forestry sector demonstration activities and develops an innovative and fair since 2008, as mandated by the Federal Ministry incentive payment scheme. for Economic Cooperation and Development Components of the FORCLIME Financial Cooperation (FC) (BMZ) and the Federal Ministry for the Module: Environment, Nature Conservation and Nuclear Safety (BMUB). Our forestry portfolio includes • Livelihood: improvement of livelihood and capacity building. REDD+, Biodiversity and Integrated Watershed • Forest ecosystem management: forest ecosystem assesment, Management, Ecosystem Restoration and an support to FSC certification, best practice of concession ASEAN Regional Programme. management, qualified data and information. • Documentation and dissemination of lessons learned. • Carbon management: carbon accounting, remote sensing, GIS, and terestrial inventory, benefit sharing financing / carbon Where we work payment. • Carbon management and land use planning: carbon monitoring at site and district level, support communities to conduct .Tanjung Selor carbon monitoring. -

M.V. Solita's Passage Notes

M.V. SOLITA’S PASSAGE NOTES SABAH BORNEO, MALAYSIA Updated August 2014 1 CONTENTS General comments Visas 4 Access to overseas funds 4 Phone and Internet 4 Weather 5 Navigation 5 Geographical Observations 6 Flags 10 Town information Kota Kinabalu 11 Sandakan 22 Tawau 25 Kudat 27 Labuan 31 Sabah Rivers Kinabatangan 34 Klias 37 Tadian 39 Pura Pura 40 Maraup 41 Anchorages 42 2 Sabah is one of the 13 Malaysian states and with Sarawak, lies on the northern side of the island of Borneo, between the Sulu and South China Seas. Sabah and Sarawak cover the northern coast of the island. The lower two‐thirds of Borneo is Kalimantan, which belongs to Indonesia. The area has a fascinating history, and probably because it is on one of the main trade routes through South East Asia, Borneo has had many masters. Sabah and Sarawak were incorporated into the Federation of Malaysia in 1963 and Malaysia is now regarded a safe and orderly Islamic country. Sabah has a diverse ethnic population of just over 3 million people with 32 recognised ethnic groups. The largest of these is the Malays (these include the many different cultural groups that originally existed in their own homeland within Sabah), Chinese and “non‐official immigrants” (mainly Filipino and Indonesian). In recent centuries piracy was common here, but it is now generally considered relatively safe for cruising. However, the nearby islands of Southern Philippines have had some problems with militant fundamentalist Muslim groups – there have been riots and violence on Mindanao and the Tawi Tawi Islands and isolated episodes of kidnapping of people from Sabah in the past 10 years or so.