I Fly, Through Lacking Feathers, with Your Wings

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Agents of Death: Reassessing Social Agency and Gendered Narratives of Human Sacrifice in the Viking Age

Agents of Death: Reassessing Social Agency and Gendered Narratives of Human Sacrifice in the Viking Age Marianne Moen & Matthew J. Walsh This article seeks to approach the famous tenth-century account of the burial of a chieftain of the Rus, narrated by the Arab traveller Ibn Fadlan, in a new light. Placing focus on how gendered expectations have coloured the interpretation and subsequent archaeological use of this source, we argue that a new focus on the social agency of some of the central actors can open up alternative interpretations. Viewing the source in light of theories of human sacrifice in the Viking Age, we examine the promotion of culturally appropriate gendered roles, where women are often depicted as victims of male violence. In light of recent trends in theoretical approaches where gender is foregrounded, we perceive that a new focus on agency in such narratives can renew and rejuvenate important debates. Introduction Rus on the Volga, from a feminist perspective rooted in intersectional theory and concerns with agency While recognizing gender as a culturally significant and active versus passive voices. We present a number and at times socially regulating principle in Viking of cases to support the potential for female agency in Age society (see, for example, Arwill-Nordbladh relation to funerary traditions, specifically related to 1998; Dommasnes [1991] 1998;Jesch1991;Moen sacrificial practices. Significantly, though we have situ- 2011; 2019a; Stalsberg 2001), we simultaneously high- ated this discussion in Viking Age scholarship, we light the dangers inherent in transferring underlying believe the themes of gendered biases in ascribing modern gendered ideologies on to the past. -

Ikonotheka 30, 2020

IKONOTHEKA 30, 2020 Tomáš Murár insTiTuTe oF arT hisTory, czech academy oF sciences, czech republic orcid: 0000-0002-3418-1941 https://doi.org/10.31338/2657-6015ik.30.1 “A work of art is an object that necessitates contemplation”. Latency of visual studies within the Vienna School of Art History? Abstract This article investigates a research method of the so-called Vienna School of Art History, mainly its transformation by Max Dvořák around the First World War. The article suggests the possible influence of Georg Simmel’s philosophy on Dvořák in this time, evident mainly in Dvořák’s interpretation of Pieter Bruegel the Elder’s art, written by Dvořák in 1920 and published posthumously in 1921. This another view on the Vienna School of Art History is then researched in writings on Pieter Bruegel the Elder by Dvořák’s students Hans Sedlmayr and Charles de Tolnay when Tolnay extended Dvořák’s thinking and Sedlmayr challenged its premises – both Tolnay and Sedlmayr thus in the same time interpreted Bruegel’s art differently, even though they were both Dvořák’s students. The article then suggests a possible interpretative relationship of the Vienna School of Art History after its transformation by Max Dvořák with today’s approaches to art (history), mainly with the so-called visual studies. Keywords: Max Dvořák, Vienna School of Art History, Georg Simmel, Visual Studies, Charles de Tolnay, Hans Sedlmayr. Introduction In Max Dvořák’s text on the art of Pieter Bruegel the Elder, written in 1920 and published posthumously in 1921,1 a reference to Georg Simmel’s interpretation of 1 M. -

Sources of Donatello's Pulpits in San Lorenzo Revival and Freedom of Choice in the Early Renaissance*

! " #$ % ! &'()*+',)+"- )'+./.#')+.012 3 3 %! ! 34http://www.jstor.org/stable/3047811 ! +565.67552+*+5 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp. JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use provides, in part, that unless you have obtained prior permission, you may not download an entire issue of a journal or multiple copies of articles, and you may use content in the JSTOR archive only for your personal, non-commercial use. Please contact the publisher regarding any further use of this work. Publisher contact information may be obtained at http://www.jstor.org/action/showPublisher?publisherCode=caa. Each copy of any part of a JSTOR transmission must contain the same copyright notice that appears on the screen or printed page of such transmission. JSTOR is a not-for-profit organization founded in 1995 to build trusted digital archives for scholarship. We work with the scholarly community to preserve their work and the materials they rely upon, and to build a common research platform that promotes the discovery and use of these resources. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. http://www.jstor.org THE SOURCES OF DONATELLO'S PULPITS IN SAN LORENZO REVIVAL AND FREEDOM OF CHOICE IN THE EARLY RENAISSANCE* IRVING LAVIN HE bronze pulpits executed by Donatello for the church of San Lorenzo in Florence T confront the investigator with something of a paradox.1 They stand today on either side of Brunelleschi's nave in the last bay toward the crossing.• The one on the left side (facing the altar, see text fig.) contains six scenes of Christ's earthly Passion, from the Agony in the Garden through the Entombment (Fig. -

ANCIENT TERRACOTTAS from SOUTH ITALY and SICILY in the J

ANCIENT TERRACOTTAS FROM SOUTH ITALY AND SICILY in the j. paul getty museum The free, online edition of this catalogue, available at http://www.getty.edu/publications/terracottas, includes zoomable high-resolution photography and a select number of 360° rotations; the ability to filter the catalogue by location, typology, and date; and an interactive map drawn from the Ancient World Mapping Center and linked to the Getty’s Thesaurus of Geographic Names and Pleiades. Also available are free PDF, EPUB, and MOBI downloads of the book; CSV and JSON downloads of the object data from the catalogue and the accompanying Guide to the Collection; and JPG and PPT downloads of the main catalogue images. © 2016 J. Paul Getty Trust This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ or send a letter to Creative Commons, PO Box 1866, Mountain View, CA 94042. First edition, 2016 Last updated, December 19, 2017 https://www.github.com/gettypubs/terracottas Published by the J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles Getty Publications 1200 Getty Center Drive, Suite 500 Los Angeles, California 90049-1682 www.getty.edu/publications Ruth Evans Lane, Benedicte Gilman, and Marina Belozerskaya, Project Editors Robin H. Ray and Mary Christian, Copy Editors Antony Shugaar, Translator Elizabeth Chapin Kahn, Production Stephanie Grimes, Digital Researcher Eric Gardner, Designer & Developer Greg Albers, Project Manager Distributed in the United States and Canada by the University of Chicago Press Distributed outside the United States and Canada by Yale University Press, London Printed in the United States of America Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: J. -

Bruegel in Black and White Three Grisailles Reunited 2 Bruegel in Black and White Three Grisailles Reunited

Bruegel in Black and White Three Grisailles Reunited 2 Bruegel in Black and White Three Grisailles Reunited Karen Serres with contributions by Dominique Allart, Ruth Bubb, Aviva Burnstock, Christina Currie and Alice Tate-Harte First published to accompany Bruegel in Black and White: Three Grisailles Reunited The Courtauld Gallery, London, 4 February – 8 May 2016 The Courtauld Gallery is supported by the Higher Education Funding Council for England (hefce) Copyright © 2016 Texts copyright © the authors All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording or any storage or retrieval system, without the prior permission in writing from the copyright holder and publisher. isbn 978 1 907372 94 0 British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Produced by Paul Holberton publishing 89 Borough High Street, London se1 1nl www.paul-holberton.net Designed by Laura Parker www.parkerinc.co.uk Printing by Gomer Press, Llandysul front cover and page 7: Christ and the Woman Taken in Adultery (cat. 3), detail frontispiece: Three Soldiers, 1568 (cat. 8), detail page 8: The Death of the Virgin, c. 1562–65 (cat. 1), detail contributors to the catalogue da Dominique Allart ab Aviva Burnstock rb Ruth Bubb cc Christina Currie ks Karen Serres at-h Alice Tate-Harte Foreword This focused exhibition brings together for the first At the National Trust, special thanks are due to David time Pieter Bruegel the Elder’s three surviving grisaille Taylor, Christine Sitwell, Fernanda Torrente and the staff paintings and considers them alongside closely related at Upton House. -

Simonetta Cattaneo Vespucci: Beauty. Politics, Literature and Art in Early Renaissance Florence

! ! ! ! ! ! ! SIMONETTA CATTANEO VESPUCCI: BEAUTY, POLITICS, LITERATURE AND ART IN EARLY RENAISSANCE FLORENCE ! by ! JUDITH RACHEL ALLAN ! ! ! ! ! ! ! A thesis submitted to the University of Birmingham for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Department of Modern Languages School of Languages, Cultures, Art History and Music College of Arts and Law University of Birmingham September 2014 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. ABSTRACT ! My thesis offers the first full exploration of the literature and art associated with the Genoese noblewoman Simonetta Cattaneo Vespucci (1453-1476). Simonetta has gone down in legend as a model of Sandro Botticelli, and most scholarly discussions of her significance are principally concerned with either proving or disproving this theory. My point of departure, rather, is the series of vernacular poems that were written about Simonetta just before and shortly after her early death. I use them to tell a new story, that of the transformation of the historical monna Simonetta into a cultural icon, a literary and visual construct who served the political, aesthetic and pecuniary agendas of her poets and artists. -

Michelangelo Buonarroti Artstart – 3 Dr

Michelangelo Buonarroti ArtStart – 3 Dr. Hyacinth Paul https://www.hyacinthpaulart.com/ The genius of Michelangelo • Renaissance era painter, sculptor, poet & architect • Best documented artist of the 16th century • He learned to work with marble, a chisel & a hammer as a young child in the stone quarry’s of his father • Born 6th March, 1475 in Caprese, Florence, Italy • Spent time in Florence, Bologna & Rome • Died in Rome 18th Feb 1564, Age 88 Painting education • Did not like school • 1488, age 13 he apprenticed for Domenico Ghirlandaio • 1490-92 attended humanist academy • Worked for Bertoldo di Giovanni Famous paintings of Michelangelo The Sistine Chapel Ceiling – (1508-12) Vatican, Rome Famous paintings of Michelangelo Doni Tondo (Holy Family) (1506) – Uffizi, Florence Famous paintings of Michelangelo The Creation of Adam (1508-12) – Vatican, Rome Famous paintings of Michelangelo The Last Judgement - (1508-12) – Vatican, Rome Famous paintings of Michelangelo Ignudo (1509) – Vatican, Rome Famous paintings of Michelangelo The Drunkenness of Noah - (1508-12) – Vatican, Rome Famous paintings of Michelangelo The Deluge - (1508-12) – Vatican, Rome Famous paintings of Michelangelo The First day of creation - - (1508-12) – Vatican, Rome Famous paintings of Michelangelo The Prophet Jeremiah - (1508-12) – Vatican, Rome Famous paintings of Michelangelo The last Judgement - (1508-12) – Vatican, Rome Famous paintings of Michelangelo The Crucifixion of St. Peter - (1546-50) – Vatican, Rome Only known Self Portrait Famous paintings of Michelangelo -

Michelangelo's David-Apollo

Michelangelo’s David-Apollo , – , 106284_Brochure.indd 2 11/30/12 12:51 PM Giorgio Vasari, Michelangelo Michelangelo, David, – Buonarroti, woodcut, from Le vite , marble, h. cm (including de’ più eccellenti pittori, scultori e base). Galleria dell’Accademia, architettori (Florence, ). Florence National Gallery of Art Library, Washington, Gift of E. J. Rousuck The loan of Michelangelo’s David-Apollo () from a sling over his shoulder. The National Gallery of Art the Museo Nazionale del Bargello, Florence, to the owns a fteenth-century marble David, with the head of National Gallery of Art opens the Year of Italian Culture, Goliath at his feet, made for the Martelli family of Flor- . This rare marble statue visited the Gallery once ence (. ). before, more than sixty years ago, to reafrm the friend- In the David-Apollo, the undened form below the ship and cultural ties that link the peoples of Italy and right foot plays a key role in the composition. It raises the United States. Its installation here in coincided the foot, so that the knee bends and the hips and shoul- with Harry Truman’s inaugural reception. ders shift into a twisting movement, with the left arm The ideal of the multitalented Renaissance man reaching across the chest and the face turning in the came to life in Michelangelo Buonarroti ( – ), opposite direction. This graceful spiraling pose, called whose achievements in sculpture, painting, architecture, serpentinata (serpentine), invites viewers to move and poetry are legendary (. ). The subject of this around the gure and admire it from every angle. Such statue, like its form, is unresolved. -

Lesson 09: Michelangelo- from High Renaissance to Mannerism

East Tennessee State University Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University Art Appreciation Open Educational Resource 2020 Lesson 09: Michelangelo- From High Renaissance to Mannerism Marie Porterfield Barry East Tennessee State University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.etsu.edu/art-appreciation-oer Part of the Art and Design Commons, and the History of Art, Architecture, and Archaeology Commons Editable versions are available for this document and other Art Appreciation lessons at https://dc.etsu.edu/art-appreciation-oer. Recommended Citation Barry, Marie Porterfield, "Lesson 09: Michelangelo- rF om High Renaissance to Mannerism" (2020). Art Appreciation Open Educational Resource. East Tennessee State University: Johnson City. https://dc.etsu.edu/art-appreciation-oer/10 This Book Contribution is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Art Appreciation Open Educational Resource by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. “Michelangelo from High Renaissance to Mannerism” is part of the ART APPRECIATION Open Educational Resource by Marie Porterfield Barry East Tennessee State University, 2020 Introduction This course explores the world’s visual arts, focusing on the development of visual awareness, assessment, and appreciation by examining a variety of styles from various periods and cultures while emphasizing the development of a common visual language. The materials are meant to foster a broader understanding of the role of visual art in human culture and experience from the prehistoric through the contemporary. This is an Open Educational Resource (OER), an openly licensed educational material designed to replace a traditional textbook. -

Michelangelo Buonarotti

MICHELANGELO BUONAROTTI Portrait of Michelangelo by Daniele da Volterra COMPILED BY HOWIE BAUM Portrait of Michelangelo at the time when he was painting the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel. by Marcello Venusti Hi, my name is Michelangelo di Lodovico Buonarroti Simoni, but you can call me Michelangelo for short. MICHAELANGO’S BIRTH AND YOUTH Michelangelo was born to Leonardo di Buonarrota and Francesca di Neri del Miniato di Siena, a middle- class family of bankers in the small village of Caprese, in Tuscany, Italy. He was the 2nd of five brothers. For several generations, his Father’s family had been small-scale bankers in Florence, Italy but the bank failed, and his father, Ludovico di Leonardo Buonarroti Simoni, briefly took a government post in Caprese. Michelangelo was born in this beautiful stone home, in March 6,1475 (546 years ago) and it is now a museum about him. Once Michelangelo became famous because of his beautiful sculptures, paintings, and poetry, the town of Caprese was named Caprese Michelangelo, which it is still named today. HIS GROWING UP YEARS BETWEEN 6 AND 13 His mother's unfortunate and prolonged illness forced his father to place his son in the care of his nanny. The nanny's husband was a stonecutter, working in his own father's marble quarry. In 1481, when Michelangelo was six years old, his mother died yet he continued to live with the pair until he was 13 years old. As a child, he was always surrounded by chisels and stone. He joked that this was why he loved to sculpt in marble. -

Last Judgment” Habent Sua Fata Libelli

Sun Symbolism and Cosmology in Michelangelo’s “Last Judgment” Habent sua fata libelli SIXTEENTH CENTURY ESSAYS &STUDIES SERIES General Editor RAYMON D A. MENTZER Montana State University—Bozeman EDITORIAL BOARD OF SIXTEENTH CENTURY ESSAYS &STUDIES ELAINE BEILIN MARY B. MCKINLEY Framingham State College University of Virginia MIRIAM USHER CHRISMAN HELEN NADER University of Massachusetts—Amherst University of Arizona BARBARA B. DIEFENDORF CHARLES G. NAUERT Boston University University of Missiouri, Colmubia PAULA FINDLEN THEODORE K. RABB Stanford University Princeton University SCOTT H.HENDRIX MAX REINHART Princeton Theological Seminary University of Georgia JANE CAMPBELL HUTCHISON JOHN D. ROTH University of Wisconsin—Madison Goshen College CHRISTIANE JOOST-GAUGIER ROBERT V. S CHNUCKER University of New Mexico Truman State University, emeritus ROBERT M. KINGDON NICHOLAS TERPSTRA University of Wisconsin, Emeritus University of Toronto ROGER MANNING MERRY WIESNER-HANKS Cleveland State University University of Wisconsin–Milwaukee Copyright © 2000 Truman State University Press, Kirksville, MO 63501 www2.truman.edu/tsup All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Shrimplin, Valerie Sun-symbolism and cosmology in Michelangelo’s Last Judgment / by Valerie Shrimplin. p. cm. — (Sixteenth century essays & studies ; v. 46) Based on the author’s thesis (doctoral—University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, 1991). Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0-943549-65-5 (Alk. paper) 1. Michelangelo Buonarroti, 1475–1564. Last Judgment. 2. Michelangelo Buonarroti, 1475–1564 Themes, motives. 3. Cosmology in art. 4. Symbolism in art. 5. Judgment Day in art. I. Title. II. Series. ND623.B9 A69 2000 759.5—dc 21 98-006646 CIP Cover: Teresa Wheeler, Truman State University designer Composition: BookComp, Inc. -

(Michelle-Erhardts-Imac's Conflicted Copy 2014-06-24).Pages

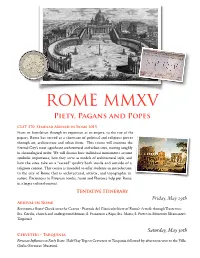

ROME MMXV Piety, Pagans and Popes CLST 370: Seminar Abroad in Rome 2015 From its foundation through its expansion as an empire, to the rise of the papacy, Rome has served as a showcase of political and religious power through art, architecture and urban form. This course will examine the Eternal City’s most significant architectural and urban sites, moving roughly in chronological order. We will discuss how individual monuments assume symbolic importance, how they serve as models of architectural style, and how the sites take on a “sacred” quality both inside and outside of a religious context. This course is intended to offer students an introduction to the city of Rome that is architectural, artistic, and topographic in nature. Excursions to Etruscan tombs, Assisi and Florence help put Rome in a larger cultural context. " Tentative Itinerary" Friday, May 29th! Arrival in Rome Benvenuto a Roma! Check into the Centro - Piazzale del Gianicolo (view of Rome) -A walk through Trastevere: Sta. Cecilia, church and underground domus; S. Francesco a Ripa; Sta. Maria; S. Pietro in Montorio (Bramante’s Tempietto)." Saturday, May 30th! Cerveteri - Tarquinia Etruscan Influences on Early Rome. Half-Day Trip to Cerveteri or Tarquinia followed by afternoon visit to the Villa " Giulia (Etruscan Museum). ! Sunday, May 31st! Circus Flaminius Foundations of Early Rome, Military Conquest and Urban Development. Isola Tiberina (cult of Asclepius/Aesculapius) - Santa Maria in Cosmedin: Ara Maxima Herculis - Forum Boarium: Temple of Hercules Victor and Temple of Portunus - San Omobono: Temples of Fortuna and Mater Matuta - San Nicola in Carcere - Triumphal Way Arcades, Temple of Apollo Sosianus, Porticus Octaviae, Theatre of Marcellus.