The Musical Number As Feminist Intervention in Crazy Ex-Girlfriend

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Announcement

Announcement 56 articles, 2016-05-25 18:01 1 venice architecture biennale: antarctic pavilion the pavilion will showcase visuals that underline possibilities of new (0.01/1) forms of architecture, planning, thinking for the vast tundra. 2016-05-25 10:40 1KB www.designboom.com 2 Lee Kit: Hold your breath, dance slowly “Hold your breath, dance slowly,” invites artist Lee Kit. As you walk into the dimly lit galleries, wandering from space to space, or nook to (0.01/1) nook, you find yourself doing just that: holding your... 2016-05-25 12:13 836Bytes blogs.walkerart.org 3 alain silberstein adds a bit of pop to MB&F's LM1 with his signature use of bold shapes + colors highlighting the french creative's meticulously practical approach to artistic design, the 'LM1 silberstein' is serious watchmaking. seriously playful. 2016-05-25 16:01 8KB www.designboom.com 4 Building Bridges: Symposium at the Fondazione Sandretto Re Rebaudengo This past weekend, Fondazione Sandretto Re Rebaudengo in Turin hosted Building Bridges, a symposium reflecting upon curatorial practice and how curators move from educational to institutional context... 2016-05-25 13:00 972Bytes blogs.walkerart.org 5 On the Gaze in the Era of Visual Salamis Our attention is not focused on a singular image, but is distributed along the image’s path. 2016-05-25 17:13 12KB rhizome.org 6 Devendra Banhart + Band* Rodrigo Amarante Hecuba Harold Budd + Brad Ellis + Veda Hille To spark discussion, the Walker invites Twin Cities artists and critics to write overnight reviews of our performances. -

Distribution Company Argentina

Presenta CÓMO LO HACE? (I DON´T KNOW HOW SHE DOES IT) Dirigida por Doug McGrath Sarah Jessica Parker Greg Kinnear Pierce Brosnan Olivia Munn Christina Hendricks SINOPSIS BREVE Durante el día, Kate Reddy (Parker) trabaja sin parar en una firma de gestión financiera en Boston. Al caer la noche, vuelve a casa para reencontrarse con su devoto esposo Richard (Kinnear), un arquitecto que acaba de perder su trabajo, y sus dos pequeños hijos. Este precario equilibrio entre trabajo y familia es el mismo que mantiene a diario la mordaz Allison (Christina Hendricks), la mejor amiga y compañera de trabajo de Kate, y el que trata de evitar a toda costa la joven Momo (Olivia Munn), la competente subalterna de Kate con fobia a los niños. Cuando Kate recibe un importante encargo que la obliga a realizar frecuentes viajes a Nueva York, Richard consigue a su vez el trabajo de sus sueños, situación que debilita el delgado hilo que mantiene unido al matrimonio. Para complicar las cosas, el nuevo y encantador colega de Kate, Jack Abelhammer (Pierce Brosnan), resulta ser una inesperada tentación para ella. SINOPSIS Conozcan a Kate Reddy (Sarah Jessica Parker): esposa, madre, mujer profesional y malabarista por excelencia. La vida de Kate no para un segundo pero es bastante genial. Tiene un marido maravilloso, Richard (Greg Kinnear), un arquitecto que ha comenzado recientemente a trabajar independientemente y con quien tiene dos hijos: Emily (Emma Rayne Lyle), de seis años, y Ben (Theodore y Julius Goldberg), que adora por completo a su madre. Tiene también un trabajo que le encanta: es gerente de inversiones en una firma de Nueva York con sede de Boston. -

Current, March 20, 2017

University of Missouri, St. Louis IRL @ UMSL Current (2010s) Student Newspapers 3-20-2017 Current, March 20, 2017 University of Missouri-St. Louis Follow this and additional works at: https://irl.umsl.edu/current2010s Recommended Citation University of Missouri-St. Louis, "Current, March 20, 2017" (2017). Current (2010s). 258. https://irl.umsl.edu/current2010s/258 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Newspapers at IRL @ UMSL. It has been accepted for inclusion in Current (2010s) by an authorized administrator of IRL @ UMSL. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Vol. 50 Issue 1528 The Current March 20, 2017 UMSL’S INDEPENDENT STUDENT NEWS UMSL Students Win $10,000 in Hackathon, Law Experts Share Have Opportunity to Incubate Business Insight at Leah Jones Features Editor Legal Career ustin Reusnow, junior, com- Jputer science; Omar Salih, in- Symposium formation systems; Sam Luebbers, graduate, information systems; Lori Dresner Chau Tran, senior, information News Editor systems; Kyle Hopfer, junior, infor- mation systems, and Alex Nuetzel, egal experts shared their sophomore, computer science at Linsight and offered advice to the University of Missouri–Colum- students considering law school at bia, have collectively won $10,000 the Choosing a Law School and Le- and the opportunity to create and gal Career Symposium in Century incubate a business through the Room C of the Millennium Student University of Missouri–St. Louis’ Center at the University of Mis- Accelerate program. This is all be- souri–St. Louis on the afternoon of fore any of them have graduated March 16. from their respective degree tracks. -

The Talk of the Town Continues…

The Talk of the Town continues… “Kay Thompson was a human dynamo. My brothers and I were constantly swept up by her brilliance. Sam Irvin has captured all of this in his incredible book. I know you will thoroughly enjoy reading it.” – DON WILLIAMS, OF KAY THOMPSON & THE WILLIAMS BROTHERS “It’s an amazing book! Sam Irvin has captured Ms. T. to a T. I just re-read it and liked it even better the second time around.” – DICK WILLIAMS, OF KAY THOMPSON & THE WILLIAMS BROTHERS “To me, Kay was the Statue of Liberty. I couldn’t imagine how a book could do her justice but, by golly, Sam Irvin has done it. You won’t be able to put it down.” – BEA WAIN, OF KAY THOMPSON’S RHYTHM SINGERS “Kay was the hottest thing that ever hit the town and one of the most captivating women I’ve ever met in my life. There’ll never be another one like her, that’s for sure. A thorough examination of her astounding life was long overdue and I can’t imagine a better portrait than the one Sam Irvin has written. Heaven.” – JULIE WILSON “This fabulous Kay Thompson book totally captured her marvelous enthusiasm and talent and I’m delighted to be a part of it. I adore the cover with enchanting Eloise and the great picture of Kay in all her intense spirit!” – PATRICE MUNSEL “Thank you, Sam, for bringing Kay so richly and awesomely ‘back to life.’ Adventuring with Kay through your exciting book is like time-traveling through an incredible century of showbiz.” – EVELYN RUDIE, STAR OF PLAYHOUSE 90: ELOISE “At Metro… she scared the shit out of me! At Paramount… while shooting Funny Face… I got to know and love her. -

Printer Friendly Version

RAY COLCORD COMPOSER SELECTED FILMOGRAPHY THE KING'S GUARD – Jonathan Tydor, Director-Shoreline Entertainment Starring Eric Roberts, Ron Perlman and Lesley-Anne Down HEARTWOOD – Lanny Cotler, Director – Porchlight Entertainment/ Lions Gate Releasing Starring Jason Robards and Hilary Swank THE PAPER BRIGADE – Blair Treu, Director -Leucadia Films / Walt Disney Company Starring Kyle Howard, Robert Englund and Bibi Osterwald WISH UPON A STAR – Blair Treu, Director - Leucadia Films / The Walt Disney Company Starring Katherine Heigl and Danielle Harris AMITYVILLE DOLLHOUSE – Steve White, Director -Spectacor Films/ Promark/ Republic Pictures Starring Robin Thomas and Allen Cutler THE SLEEPING CAR – Douglas Curtis - Vidmark Entertainment Starring David Naughton and Kevin McCarthy SONGS ALL DOGS GO TO HEAVEN II (animated film) – Larry Leker and Paul Sabella, Directors -MGM Featuring the voices of Bebe Neuwirth and Charlie Sheen BABES IN TOYLAND (animated film) – Paul Sabella, Director - MGM Featuring the voices of Lacey Chabert, James Belushi and Christopher Plummer EARTH GIRLS ARE EASY (songs) – Julien Temple, Director-Warner Bros. Starring Geena Davis, Jeff Goldblum, Julie Brown and Jim Carrey ("Big & Stupid", "Homecoming Queen's Got A Gun") ADDITIONAL MUSIC LARA CROFT TOMB RAIDER II - Jan de Bont, Director - Paramount Pictures / Mutual Film Company THE GENERAL'S DAUGHTER – Simon West, Director - Paramount Starring John Travolta, Madeleine Stowe, James Cromwell, James Woods and Clarence Williams III DUMB & DUMBER - Peter Farrelly, Director- -

Ellie Smith 1St Assistant Director

ELLIE SMITH 1ST ASSISTANT DIRECTOR TELEVISION A LEAGUE OF THEIR OWN (Pilot) Sony/Amazon Prod: Abbi Jacobson, Will Graham, Michael Cedar Dir: Jamie Babbit THE STRANGER (Limited series) Fox 21 TV/Quibi Prod: Veena Sud, Jeffrey Katzenberg Dir: Veena Sud LIGHT AS A FEATHER (Season 2) Hulu/Awesomeness TV Prod: Brin Lukens, Dylan Vox Dir: Alexis Ostrander PEARSON (Season 1) UCP/USA Prod: Daniel Arkin, David Bartis, Aaron Korsh, Dir: Anton Cropper Doug Liman, Gina Torres LESS THAN ZERO (Pilot) Fox 21/Hulu Prod: Craig Wright, Rebecca Sinclair, Bob Williams Dir: Brett Morgen FOURSOME (Season 4) Awesomeness TV/ Prod: Lance Lanfear, Dan Suhart Dir: Various YouTube Red THE CHI (Season 1) Fox 21 TV/Showtime Prod: Elwood Reid, Lena Waithe, Common, Aaron Kaplan Dir: Various *Nominated – Television – Peabody Awards, 2019 IDIOTSITTER (Season 2) Comedy Central Prod: Jillian Bell, Charlotte Newhouse, Dan Kuba Dir: Various GRAVES (Promo) Lionsgate TV/EPIX Prod: Joshua Michael Stern Dir: Larry Charles THE CATCH (Season 1) (2nd Unit) ABC Studios/ABC Prod: Shonda Rhimes, Kevin Dowling Dir: Various DOPE GIRLS (Pilot) MTV Prod: Harry Elfont, Deborah Kaplan, Ken Ornstein Dir: Michael Blieden SIRENS (Seasons 1 & 2) Fox 21 TV/USA Prod: Denis Leary, Jim Serpico, Tom Sellitti Dir: Various CHICAGO FIRE (Season 1) (2nd AD) Universal TV/NBC Prod: Dick Wolf, Joe Chappelle, John L. Roman Dir: Various NCIS-LA (Seasons 1 & 2) CBS TV/CBS Prod: Shane Brennan Dir: Various HEROES (Seasons 1 & 2) (2nd AD) Universal TV/NBC Prod: Tim Kring Dir: Various LAST MYSTERIES OF TITANIC -

Postmodern Visual Dynamics in Amy Heckerling's Clueless

e Interdisciplinary Journal of Popular Culture and Pedagogy Hyping the Hyperreal: Postmodern Visual Dynamics in Amy Heckerling’s Clueless Andrew Urie York University Toronto, Ontario, Canada [email protected] ABSTRACT An iconic staple of 1990s Hollywood cinema, director-screenwriter Amy Heckerling’s Clueless (1995) is a cult classic. This article examines the film’s postmodern visual dynamics, which parody hyperreal media culture and its connection to feminine teen consumerism amidst the image-saturated society of mid-’90s era Los Angeles. Keywords: Clueless; Amy Heckerling; Jane Austen; Emma; Popular Culture; Visual Culture; Film Studies; Media Studies; Postmodernism; Hyperreal 38 Volume 4, Issue 1 Hyping the Hyperreal A contemporized reworking of Jane Austen’s 1816 novel, Emma, director-screenwriter Amy Heckerling’s Clueless (1995) stands out as a notable cultural artifact of 1990s Hollywood cinema. While an abundance of scholarly articles exist on how Heckerling adapted the key plot dynamics of Austen’s novel for a postmodern audience,1 this article will largely eschew such narrative analysis in favor of focusing on the film’s unique postmodern visual dynamics, which constitute an insightful parody of hyperreal media culture and its particular connection to feminine teen consumerism amidst the image-saturated society of mid-’90s era Los Angeles. Less an adaptation of Emma than a postmodern appropriation, Clueless pays parodic homage to an oft- overlooked thematic element embedded in its source text. Transposing the decadence of Emma’s upper echelon Regency-era society for the nouveau riche decadence of Beverly Hills and its attendant culture of conspicuous consumption, the film focuses on the travails of its affluent sixteen-year-old heroine, Cher Horowitz (Alicia Silverstone), whose narcissistic preoccupations revolve around consumerism and fashion. -

Earth Girls Are Easy Actors (Cast) List

Earth Girls Are Easy Actors List (Cast) Andrea Parker https://www.listvote.com/lists/film/actors/andrea-parker-287835/movies Julie Brown https://www.listvote.com/lists/film/actors/julie-brown-524776/movies Steve Lundquist https://www.listvote.com/lists/film/actors/steve-lundquist-597975/movies Charles Rocket https://www.listvote.com/lists/film/actors/charles-rocket-325082/movies Wayne Brady https://www.listvote.com/lists/film/actors/wayne-brady-1397155/movies Nedra Volz https://www.listvote.com/lists/film/actors/nedra-volz-443508/movies Jim Carrey https://www.listvote.com/lists/film/actors/jim-carrey-40504/movies Stacey Travis https://www.listvote.com/lists/film/actors/stacey-travis-7595884/movies Julie Brown https://www.listvote.com/lists/film/actors/julie-brown-454119/movies Larry Linville https://www.listvote.com/lists/film/actors/larry-linville-1347106/movies Robia LaMorte https://www.listvote.com/lists/film/actors/robia-lamorte-448276/movies Lucy Lee Flippin https://www.listvote.com/lists/film/actors/lucy-lee-flippin-522870/movies Angelyne https://www.listvote.com/lists/film/actors/angelyne-513037/movies Damon Wayans https://www.listvote.com/lists/film/actors/damon-wayans-382420/movies Michael McKean https://www.listvote.com/lists/film/actors/michael-mckean-1384181/movies Geena Davis https://www.listvote.com/lists/film/actors/geena-davis-280098/movies Lisa Boyle https://www.listvote.com/lists/film/actors/lisa-boyle-469651/movies Jeff Goldblum https://www.listvote.com/lists/film/actors/jeff-goldblum-106706/movies Robby the https://www.listvote.com/lists/film/actors/robby-the-robot-2277376/movies Robot Rick Overton https://www.listvote.com/lists/film/actors/rick-overton-2151597/movies. -

Partners Transcript: Aline & Rachel Aline: There Was Tons and Tons of Stuff Coming out of the Writers' Room That Rachel Coul

Partners Transcript: Aline & Rachel Aline: There was tons and tons of stuff coming out of the writers' room that Rachel could not process because she was shooting. I would try and grab her when she was changing, or when she was peeing, or— (OVERLAP) Rachel: She saw me naked and peeing a lot. Aline: Yeah. Aline: My name is Aline Brosh McKenna and I'm the co-creator of Crazy Ex-Girlfriend. Rachel: My name is Rachel Bloom and I am the other co-creator of Crazy Ex-Girlfriend. Hrishikesh: Crazy Ex-Girlfriend was a genre-bending TV show—part comedy, part drama, part musical, that aired for four seasons on the CW, from 2015 to 2019. It was a show that challenged and subverted the familiar tropes of romantic comedies. And along the way, it won a Critics Choice Award, a Golden Globe Award, and four Emmys, including some for the star of the show, Rachel Bloom, who co-created it with Aline Brosh McKenna. When it comes to romantic comedies, Aline Brosh McKenna is a master of the form, having written the screenplays for 27 Dresses and The Devil Wears Prada, among others. But before Rachel and Aline got to deconstructing romantic comedies, they had a meet-cute of their own, thanks to the website Jezebel. Here’s Aline. Aline: I was in my old office, which is on the Hanson Lot and I was procrastinating. And at the time I used to read Jezebel pretty regularly, and I saw a little piece on - Rachel had a new video out. -

Teenie Weenie in a Too Big World: a Story for Fearful Children Free

FREE TEENIE WEENIE IN A TOO BIG WORLD: A STORY FOR FEARFUL CHILDREN PDF Margot Sunderland,Nicky Hancock,Nicky Armstrong | 32 pages | 03 Oct 2003 | Speechmark Publishing Ltd | 9780863884603 | English | Bicester, Oxon, United Kingdom ບິ ກິ ນີ - ວິ ກິ ພີ ເດຍ A novelty song is a type of song built upon some form of novel concept, such as a gimmicka piece of humor, or a sample of popular culture. Novelty songs partially overlap with comedy songswhich are more explicitly based on humor. Novelty songs achieved great popularity during the s and s. Novelty songs are often a parody or humor song, and may apply to a current event such as a holiday or a fad such as a dance or TV programme. Many use unusual Teenie Weenie in a Too Big World: A Story for Fearful Children, subjects, sounds, or instrumentation, and may not even be musical. It is based on their achievement Teenie Weenie in a Too Big World: A Story for Fearful Children a UK number-one single with " Doctorin' the Tardis ", a dance remix mashup of the Doctor Who theme music released under the name of 'The Timelords. Novelty songs were a major staple of Tin Pan Alley from its start in the late 19th century. They continued to proliferate in the early years of the 20th century, some rising to be among the biggest hits of the era. We Have No Bananas "; playful songs with a bit of double entendre, such as "Don't Put a Tax on All the Beautiful Girls"; and invocations of foreign lands with emphasis on general feel of exoticism rather than geographic or anthropological accuracy, such as " Oh By Jingo! These songs were perfect for the medium of Vaudevilleand performers such as Eddie Cantor and Sophie Tucker became well-known for such songs. -

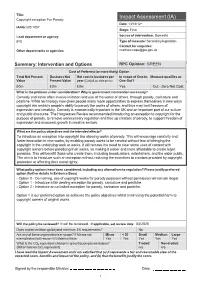

Copyright Exception for Parody Date: 13/12/12* IA No: BIS 1057 Stage: Final

Title: Impact Assessment (IA) Copyright exception For Parody Date: 13/12/12* IA No: BIS 1057 Stage: Final Lead department or agency: Source of intervention: Domestic IPO Type of measure: Secondary legislation Contact for enquiries: Other departments or agencies: [email protected] Summary: Intervention and Options RPC Opinion: GREEN Cost of Preferred (or more likely) Option Total Net Present Business Net Net cost to business per In scope of One-In, Measure qualifies as Value Present Value year (EANCB on 2009 prices) One-Out? £0m £0m £0m Yes Out - Zero Net Cost What is the problem under consideration? Why is government intervention necessary? Comedy and satire often involve imitation and use of the works of others, through parody, caricature and pastiche. While technology now gives people many more opportunities to express themselves in new ways copyright law restricts people's ability to parody the works of others, and thus may limit freedom of expression and creativity. Comedy is economically important in the UK and an important part of our culture and public discourse. The Hargreaves Review recommended introducing an exception to copyright for the purpose of parody, to remove unnecessary regulation and free up creators of parody, to support freedom of expression and economic growth in creative sectors. What are the policy objectives and the intended effects? To introduce an exception into copyright law allowing works of parody. This will encourage creativity and foster innovation in new works, by enabling parody works to be created without fear of infringing the copyright in the underlying work or works. It will remove the need to clear some uses of content with copyright owners before parodying their works, so making it easier and more affordable to create legal parodies. -

"WEIRD AL" YANKOVIC: POLKAS, PARODIES and the POWER of SATIRE by Chuck Miller Originally Published in Goldmine #514

"WEIRD AL" YANKOVIC: POLKAS, PARODIES AND THE POWER OF SATIRE By Chuck Miller Originally published in Goldmine #514 Al Yankovic strapped on his accordion, ready to perform. All he had to do was impress some talent directors, and he would be on The Gong Show, on stage with Chuck Barris and the Unknown Comic and Jaye P. Morgan and Gene Gene the Dancing Machine. "I was in college," said Yankovic, "and a friend and I drove down to LA for the day, and auditioned for The Gong Show. And we did a song called 'Mr. Frump in the Iron Lung.' And the audience seemed to enjoy it, but we never got called back. So we didn't make the cut for The Gong Show." But while the Unknown Co mic and Gene Gene the Dancing Machine are currently brain stumpers in 1970's trivia contests, the accordionist who failed the Gong Show taping became the biggest selling parodist and comedic recording artist of the past 30 years. His earliest parodies were recorded with an accordion in a men's room, but today, he and his band have replicated tracks so well one would think they borrowed the original master tape, wiped off the original vocalist, and superimposed Yankovic into the mix. And with MTV, MuchMusic, Dr. Demento and Radio Disney playing his songs right out of the box, Yankovic has reached a pinnacle of success and longevity most artists can only imagine. Alfred Yankovic was born in Lynwood, California on October 23, 1959. Seven years later, his parents bought him an accordion for his birthday.