Participative Approaches to Hedgerow Conservation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Feedback 63 - 1 Welcome to the 63Rd Edition of Our Bi-Annual Magazine in This Issue

feedback Issue 63 / Spring 2020 Reg Charity No: 299 835 Waterleat, Ashburton www.barnowltrust.org.uk Devon TQ13 7HU Spring 2020 - Feedback 63 - 1 Welcome to the 63rd edition of our bi-annual magazine In this issue ... ‘Feedback’. It has been a very busy few months here at the Barn Owl Trust with the Conservation Team working hard answering enquiries, dealing with injured owls (see Bird News page 6), Welcome to Feedback 2 holding Barn Owl training courses for ecologists, managing Diary Dates 2 our nature reserve and holding guided walks (see LLP Update BOT News 3 page 4), erecting and monitoring nestboxes as well as giving out habitat advice to landowners. Rick, our Conservation Officer, LLP Update 4 explains what our nestboxing work entails in the article ‘Winter Winter Nestboxing 5 Nestboxing’ on page 5. In Memoriam 5 Bird News 6 In addition to the day-to-day tasks the team has also been involved in various other projects including gathering together Barn Owls in Malaysia 7 data for the newest State of the UK Barn Owl Population report A Place for Grasslands 8 due to be published soon, further research on Barn Owl road Feeling Blue or Going Green? 9 mortality, and preparing for Rick and Mateo’s upcoming visit to the Ulster Wildlife Trust (see News Bites page 3). More news on The Owly Inbox 10 these events to follow in issue 64. Barn Owls in Canada 11 More BOT News 12 It is always a pleasure to welcome visitors working in Barn Owl Fundraising News 13 conservation across the globe and in November Shakinah from the Barn Owl and Rodent Research Group in Malaysia visited Judith’s Journal 14 us for a couple of weeks hoping to gather knowledge and Team Talk 15 information to take back home. -

Standing Dead Trees in the Urban Forest

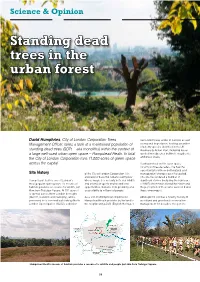

Science & Opinion Standing dead trees in the urban forest David Humphries, City of London Corporation Trees Kenwood Estate) and is of national as well Management Officer, takes a look at a maintained population of as regional importance, hosting a number of priority species identified in the UK standing dead trees (SDTs – aka monoliths) within the context of Biodiversity Action Plan, including lesser a large well-used urban open space – Hampstead Heath. In total spotted woodpecker, bullfinch, stag beetle the City of London Corporation runs 11,000 acres of green space and grass snake. across the capital. Having worked on this open space for almost three decades, I’ve had the opportunity to witness both natural and Site history of the City of London Corporation. It is management changes over that period. an island of beautiful ‘urban countryside’ The site has endured a number of Hampstead Heath is one of London’s whose magic lies not only in its rich wildlife significant storms (including the hurricane most popular open spaces. Its mosaic of and extensive sports and recreational of 1987) which have altered the Heath and habitats provides a resource for wildlife just opportunities, but also in its proximity and the perception of those who work on it and 6km from Trafalgar Square. At 791 acres it accessibility to millions of people. those who enjoy it. is spread across three London boroughs (Barnet, Camden and Haringey), and is As a Site of Metropolitan Importance, Although the site has a healthy history of preserved in its semi-natural state by North Hampstead Heath provides buffer land to woodland and grassland conservation London Open Spaces (NLOS), a division the neighbouring SSSI (English Heritage’s management for decades, the generic Hampstead Heath’s mosaic of habitats provides a resource for wildlife and people just 6km from Trafalgar Square. -

Simon Braidman's Bluebell Heath Project Notes 2014

REPORT FOR WORK PARTY SUNDAY 5TH JANUARY 2014 ATTENDEES: Simon Braidman, John Winter, Neville Day, Mo Farhand, John Bugler, Josh Kalms, Sue Kable and Rajinder Hayer 10.30am to 2.00pm Weather : clear then clouding over, light rain shower then dull dry 5 degrees centigrade TASK: Work along the top edge of Bluebell Heath, removing scrub saplings. Secondary tasks: 1)thinning scrub retention blocks by taking out lower branches 2) removing Holly from behind eastern end of bare earth bank 3) checking on whether the bare earth bank stops water flow across New Scrape 4) checking on flytips on Heathbourne Road and new really bad one on Common Road It was really great to see people after the long Christmas break. It is important to control the scrub level in Bluebell Heath. A lot of money has been spent re‐opening the clearing and the danger is the area, re‐scrubbing up. The most insidious threat are the masses of tiny scrub saplings which look like whole areas have had the Woodland Trust in, planting trees. Young scrub is an important habitat but it is superabundant and the quicker one can deal with them the better. The extremely heavy rainfall should make it easier to remove the whole tree. If only it was that easy. The reality is that these are not single trees often each flimsy stem is attached to others by an underground horizontal root. This root can be 2inches thick. Also there are living stumps with suckers growing from them sometimes with horizontal roots wrapped around them or even fused to them. -

Sadlers Wood Annual Review 2020

Sadlers Wood Annual Review 2020 North Norfolk District Council 1/1/21 Contents Contents Contents ................................................................................................. 1 Introduction – Welcome to Sadlers Wood .......................................................... 2 Health Safety and Security ........................................................................... 5 Maintenance of Equipment, Buildings and Landscapes .......................................... 8 Environmental Management ........................................................................ 12 Biodiversity, Landscape and Heritage ............................................................ 14 Community Involvement ............................................................................ 17 Marketing and Communication .................................................................... 20 Conservation and Woodland Management Work Plan .......................................... 24 Site Risk Assessment ................................................................................... 0 Introduction – Welcome to Sadlers Wood Abstract This annual review outlines the management work, activities, projects, development and general progress made by North Norfolk District Council’s Countryside Service against Sadlers Wood Management Plan in 2020, and forms the basis of the authority’s application for continued Green Flag Award status. About Sadlers Wood and the surrounding open space lies at the eastern side of the market town of North Walsham -

Pretty Corner Woods Annual Review 2020

Pretty Corner Woods Annual Review 2020 North Norfolk District Council 1/1/21 Contents Contents Contents ................................................................................................. 1 Introduction – Welcome to Pretty Corner Woods ................................................. 2 Health Safety and Security ........................................................................... 6 Maintenance of Equipment, Buildings and Landscapes .......................................... 9 Environmental Management ........................................................................ 13 Biodiversity, Landscape and Heritage ............................................................ 15 Community Involvement ............................................................................ 17 Marketing and Communication .................................................................... 20 Conservation and Woodland Management Work Plan .......................................... 24 Site Risk Assessment ................................................................................... 0 Introduction – Welcome to Pretty Corner Woods Abstract This annual review outlines the management work, activities, projects, development and general progress made by North Norfolk District Council’s Countryside Service against Pretty Corner Woods Management Plan in 2020, and forms the basis of the authority’s application for continued Green Flag Award status. About Pretty Corner Woods, which has held Green Flag Status since 2013/14, forms part of a -

Grass Roots Magazine Winter 2018-2019

Grass Roots 1 The RHS Community Update Issue 36 • Winter 2018/2019 rhs.org.uk/get-involved Growing community Bloomers make a difference Grow a hedge Greening Grey Britain: RHS support Community orchard takes shape rhs.org.uk/get-involved 2 3 2 Welcome 3 Greening Grey Britain 2019 News 4 News 6 Growing as a force for good 8 Planting a hedge RHS / GUY HARROP 10 Reuse your garden sticks Welcome… 12 Urban orchards 14 Championing school ...to the winter issue of Grass Roots, the magazine for all community gardening groups, including Bloom and It’s Your Neighbourhood groups gardening and RHS Affiliated Societies. A very happy New Year to you all! We hope or changing tack in some way. Some of Left you’ve all enjoyed a well-deserved rest and your big ideas could possibly be helped into Volunteers and have had a chance to put your feet up after being, as part of RHS Greening Grey Britain students from Dunbar the hustle and bustle of the festive period. 2019. We are again looking for innovative Grammar School put the finishing touches Just as the buds that herald spring projects that bring different generations to a sensory garden appear in the depths of winter, many of together. Find out more on the next page. they helped create for your plans for the year ahead may have been people with dementia and their carers as germinating for some time. We are excited Best wishes and happy gardening, part of Greening Grey to see some of those plans take shape as RHS / JULIE HOWDEN Britain 2018. -

Lowland Book 170618.Indd

© Peter Thompson Nesting cover: for safe nest sites What nesting cover do gamebirds need? Ideal partridge nesting sites are in thick grassy cover, often at the base of a field boundary or on low banks - slightly raised above the general field level. The site needs to be dry, sheltered and well concealed, with plenty of “residual” grass – dead grass from the previous year that helps with camouflage39. Pheasants will also nest in these sites, but in general prefer to breed along woodland edges with plenty of shrubby cover, particularly brambles85. Nesting attempts made later in the season tend to be in crops. How do shoots provide this? Hedgerow management The UK hedgerow stock degraded in the second half of 20th century as farming policies encouraged their removal to optimise efficient mechanised farming methods. Many were retained during that period because of game interests. Hedgerows are very important for partridge nesting, in fact many studies have found that up to 75% of grey partridge nest in hedge bottoms when available39. However, the type of hedgerow is also important – for example, they should retain 68 69 The Knowledge enough dead grass from the year before at the base to provide cover for a female grey partridge or wild pheasant sitting on a nest61. The modern approach of frequent hedgerow cutting reduces the amount of dead grass available, and we recommend that hedgerows should be cut every other year, rather than annually, preferably in late winter so that the berries produced by the hedge plants can be eaten by birds. A good scheme for the farm as a whole is to cut one half or one third of hedges each year, ensuring that these are scattered across the farm rather than all in one area. -

Biodiversity and Wildlife

Natural England works for people, places and nature to conserve and enhance biodiversity, landscapes and wildlife in rural, urban, coastal and marine areas. We conserve and Wildlife on allotments enhance the natural environment for its intrinsic value, the wellbeing and enjoyment of people, and the economic prosperity it brings. www.naturalengland.org.uk © Natural England 2007 ISBN 978-1-84754-018-8 Catalogue code NE20 Written by Stephen Arnott. Designed by RR Donnelley Front cover image: Allotments are scarce in some urban areas. Judith Hanna/Natural England www.naturalengland.org.uk Wildlife on allotments Although allotments will always be to survive on intensively managed mainly used for growing food, they farmland find a refuge on allotment have other values that are now gaining sites. This leaflet will help you enhance greater recognition. They are great the conservation value of your places for healthy exercise, provide allotment, while continuing to good opportunities for socialising, and cultivate it for fruit and vegetables. put us back in touch with the earth. We all, ultimately, depend on the soil for History our foods but in this highly processed, Allotments have been around for a pre-packaged age the connection is long time. They were originally created often forgotten. for poor agricultural workers to Allotments are also an increasingly compensate them for the loss of important resource for wildlife. Many common land during the enclosures of of the plants and animals that struggle the eighteenth century. Allotments Allotments are a refuge for both people and wildlife. Peter Wakely/Natural England Fresh food and fresh air. -

Woodland Management Plan 2018-2028

Woodland Management Plan 2018-2028 Contents 1. Introduction ....................................................................................................... 1 2. Vision and Objectives ....................................................................................... 1 3. Plan Review – Achievements ........................................................................... 1 4. Woodland Survey ............................................................................................. 2 5. Protection ......................................................................................................... 5 6. Management Strategy ...................................................................................... 8 7. Stakeholder Engagement ............................................................................... 10 8. Monitoring ....................................................................................................... 11 Appendix 1: Figures ................................................................................................ 12 Appendix 2: Compartment Descriptions and Management Plans ............................ 15 1. Introduction Highgate Wood lies between Archway Road and Muswell Hill Road in the London Borough of Haringey. It covers 28 hectares, of which about 24 hectares are ancient oak and hornbeam woodland, most of the rest being amenity grassland. It is owned and managed by the City of London Corporation. A Conservation Management Plan for the Wood published in April 2013 covered all -

Final Report

Final Report Photo: Bienvenida Bauer Photo by: Bienvenida Bauer Workshop on Capacity Strengthening in Agricultural Best Management Practices for USAID and the Caribbean Implementing Partners Jarabacoa, Dominican Republic July 8th-12th , 2013 Lead by: Co-organized & facilitated by: Contents Introduction…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………1 Workshop Methodology Case Studies and Technical Presentation……………………………………………………………………………………………………..1 Field Visits……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………1 Group work………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….2 Data Synthesis………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………...3 Recommendations………………………………………………………………………………………………………3 Workshop Evaluation……..…………………………………………………………………………………………..3 Annexes: Workshop Agenda…………………………………………………………………………………………………………….…….…….4-8 BMP’s Workshop Synthesis……………………………………………………………………………………………….……..… 9-14 General BMP’s Matrix………………………………………………………………………………………………………….…….15-22 Country Matrix……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….....23-25 Crop-Specific Matrix……………………………………………………………………………………………………………...…..26-34 Workshop Evaluations & Other Commentaries.……………………………………………………………….……..….35-36 Participants List………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….37-38 Introduction The workshop was led by REDDOM, with Sun Mountain International as the co-organizer. It was a multi-country initiative with a goal to produce tangible Agricultural Best Management Practices (BMPs) for Caribbean-based existing and future USAID and Government projects -

Managing Your Woodland for Wildlife

Managing wildlife for woodland your Managing your woodland Managing your for wildlife woodland for wildlife Most woodland management has been highly beneficial for wildlife over the centuries, creating habitats which have supported a diverse flora and fauna. These range from the temporary open areas created by coppicing to veteran trees in grazed parkland. Sadly, the second part of the 20th century witnessed a period of neglect resulting in the reversion of large areas of coppice, under-thinned plantations and the loss of open space; and Buckley Peter and Blakesley David little active conservation of old-growth features. As a consequence we have seen a serious decline in woodland diversity. Many people and organisations are now in a position to do something actively to help, either as owners or custodians of woodland. This beautifully illustrated book aims to offer practical advice for those managing smaller areas of woodland for wildlife. The authors begin by introducing different woodland types – woodland plants, insects, birds, mammals, reptiles, fungi and lichens and how different management strategies will affect them. The creation of woodland open space is given particular prominence, together with other ways of improving woodland for wildlife, from conserving deadwood to putting up bat boxes. This book will appeal to small woodland owners and others with an interest in woodland management, including landowners, conservation organisations, foresters, consultants, planners, local authorities and community groups. David Blakesley and Peter Buckley Commissioned by Woodlands.co.uk have sponsored the writing and production of this book to encourage people to manage their woodlands for biodiversity and to enable them to do so Managing your woodland for wildlife David Blakesley and Peter Buckley Illustrated by Tharada Blakesley Sponsored by Woodlands.co.uk – providing woods for enjoyment and conservation Newbury, Berkshire Citation For bibliographic purposes, this book should be referred to as Blakesley, D and Buckley, GP. -

River-Medway-Towpath-Report

Document Reference: DHA-743-001 Revsion: Date: 09.06.2016 Following a full review of the preliminary ecological reports and the subsequent recommended detailed ecological surveys, a number of restoration, planting enhancement and habitat creation opportunities were identified along the River Medway between Aylesford and Barming Bridge as part of the wider towpath upgrade and widening works. In total, six locations were identified as suitable, with opportunities ranging from riverbank restoration, Dormouse habitat enhancement, bat box placement and amenity planting. Where applicable, all seed mixes and native species shrubs shall be of local provenance. *Aerial image taken from Google Earth Pro This document is to be read in conjunction with drawing DHA-743-002-006 2 AREA 1 Location: North of the M20 flyover, adjacent to the Deacon Industrial Estate Stretch: 65 lm approximately AIMS Objectives and Opportunities • Riverbank scour protection and planting enhancement with native species. • Enhance reptile and invertebrate habitats with log piles and stag beetle loggeries. • Install bat boxes on selective existing trees. Boxes to also be installed further west. Final numbers and locations to be agreed. Sketch Section 1 - 1 • Towpath width increased to 2.5m wide for shared cycle and pedestrian Towpath 2.5m Riverbank planting enhancment with Willow spiling with Existing use. habitat creation interventions wet meadow seed river wall HABITAT CREATION & ENHANCEMENT RIVERBANK PROTECTION AND PLANTING ENHANCEMENT Stag Beetle loggery using off Log piles for invertebrate A wet wildflower meadow Willow spiling will be used to Along the riverbank edge, native species including dogwood, field maple and hawthorn cuts from on-site clearance and slow worms using off mix will be seeded between protect the riverbank from erosion will be planted in random groups following clearance works.