Your Grounds

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Somerset Woodland Strategy

A Woodland Strategy for Somerset 2010 A Woodland Strategy for Somerset 2010 Contents ©ENP Introducing the Strategy 2 Mendip 20 Table of Contents 2 Sedgemoor 21 Woodland Strategy Overview 4 Taunton Deane 22 Benefits of a Somerset Woodland Strategy 4 West Somerset 23 VISION STATEMENT 5 Sensitive Landscape Areas 24 Analysis of Somerset’s Woodland Resource 6 Culture and Heritage 25 Somerset’s Woodland Resource 6 Cultural issues related to woodlands 25 Woodland distribution 6 Links with our history and a source of inspiration 25 Area of woodland 7 Ecosystem Services provided by trees and woodland 25 Woodland size 8 Recreation and access 26 Woodland species 8 The need for public access 26 Coniferous woodland 9 Accessible woodlands in Somerset 27 Hedgerow and parkland trees 10 Case Study - “The Neroche Forect Project” 28 Other elements of the woodland resource 10 Archaeology and the Historic Landscape 29 Nature Conservation 11 Historic woodland cover 29 SSSI Woodland 11 Ancient woodland 29 Importance of the designated areas 11 Ownership of ancient woodlands 30 Key woodland biodiversity types 12 Sensitive Management of Archaeological Features 31 Local Wildlife Sites 14 Case Study - “Exmoor National Park, Ancient Woodland Project” 32 Woodland wildlife of European importance 14 Historic value of hedgerow trees 33 Management for biodiversity 15 Historic landscape policy 33 Veteran Trees 16 Woodland Ownership 34 Landscape Assessment 18 Why people own Woodlands 34 Somerset Character Areas 18 Woodland ownership by Conservation bodies 35 Woodland in -

Feedback 63 - 1 Welcome to the 63Rd Edition of Our Bi-Annual Magazine in This Issue

feedback Issue 63 / Spring 2020 Reg Charity No: 299 835 Waterleat, Ashburton www.barnowltrust.org.uk Devon TQ13 7HU Spring 2020 - Feedback 63 - 1 Welcome to the 63rd edition of our bi-annual magazine In this issue ... ‘Feedback’. It has been a very busy few months here at the Barn Owl Trust with the Conservation Team working hard answering enquiries, dealing with injured owls (see Bird News page 6), Welcome to Feedback 2 holding Barn Owl training courses for ecologists, managing Diary Dates 2 our nature reserve and holding guided walks (see LLP Update BOT News 3 page 4), erecting and monitoring nestboxes as well as giving out habitat advice to landowners. Rick, our Conservation Officer, LLP Update 4 explains what our nestboxing work entails in the article ‘Winter Winter Nestboxing 5 Nestboxing’ on page 5. In Memoriam 5 Bird News 6 In addition to the day-to-day tasks the team has also been involved in various other projects including gathering together Barn Owls in Malaysia 7 data for the newest State of the UK Barn Owl Population report A Place for Grasslands 8 due to be published soon, further research on Barn Owl road Feeling Blue or Going Green? 9 mortality, and preparing for Rick and Mateo’s upcoming visit to the Ulster Wildlife Trust (see News Bites page 3). More news on The Owly Inbox 10 these events to follow in issue 64. Barn Owls in Canada 11 More BOT News 12 It is always a pleasure to welcome visitors working in Barn Owl Fundraising News 13 conservation across the globe and in November Shakinah from the Barn Owl and Rodent Research Group in Malaysia visited Judith’s Journal 14 us for a couple of weeks hoping to gather knowledge and Team Talk 15 information to take back home. -

Display PDF in Separate

Stuart Bcckhurst x 2 Senior Scientist (Quality Planning) ) £e> JTH vJsrr U T W J Vcxg locafenvironment agency plan EXE ACTION PLAN PLAN from JULY 2000 to JULY 2005 Further copies of this Action Plan can be obtained from: LEAPs (Devon Area) The Environment Agency Exminster House Miller Way Exminster Devon EX6 8AS Telephone: (01392) 444000 E-mail: [email protected] Environment Agency Copyright Waiver This report is intended to be used widely and the text may be quoted, copied or reproduced in any way, provided that the extracts are not quoted out of context and that due acknowledgement is given to the Environment Agency. However, maps are reproduced from the Ordnance Survey 1:50,000 scale map by the Environment Agency with the permission of the Controller of Her Majesty's Stationery Office, © Crown Copyright. Unauthorised reproduction infringes Crown Copyright and may lead to prosecution or civil proceedings. Licence Number GD 03177G. Note: This is not a legally or scientifically binding document. Introduction 1 . Introduction The Environment Agency We have a wide range of duties and powers relating to different aspects of environmental management. These duties are described in more detail in Section Six. We are required and guided by Government to use these duties and powers in order to help achieve the objective of sustainable development. The Brundtland Commission defined sustainable development 'os development that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs' At the heart of sustainable development is the integration of human needs and the environment within which we live. -

Nature Conservation on a Shoestring

Bulletin of the Chartered Institute of Ecology and Environmental Management Issue 98 | December 2017 Nature Conservation on a Shoestring In this issue Conservation on a Shoestring: Working for Wildlife – Pantheon: A New Resource The Mutualistic Benefits of Environmental Partnerships for Invertebrate Survey University – Nature Reserve between Water Companies Standards and Analysis Collaborations and Wildlife Trusts Welcome Information Nature Conservation on a Shoestring In Practice No. 98 December 2017 Most CIEEM members will agree that a healthy, wildlife-rich natural world is valuable ISSN 1754-4882 in its own right as well as being the foundation of our wellbeing and prosperity; Editor we depend on it and it depends on us. Yet too many forces in the world are pulling Dr Gillian Kerby ([email protected]) wildlife and people apart, unnecessarily damaging natural systems, disrupting Internal contributions ecological processes and reducing biodiversity. The turbulence of the political climate coordinator opens up major risks but also presents new opportunities for nature conservation. Mr Jason Reeves ([email protected]) We have our work cut out to turn this chaos to the advantage of the natural world. Editorial Board Mr Jonathan Barnes, Dr Kate Bayley, The Wildlife Trusts believe that everyone deserves to live in a healthy environment, Dr Andrew Cherrill, Mr Dominic Coath, rich in wildlife and full of opportunities to enjoy the natural world. By working Mr Neil Harwood, Dr Caroline McParland, together, in the places that are closest and most important to us, people can change Mrs Kate Morris, Mr Paul Rooney, the natural world for the better – whoever and wherever we are – for ourselves and Mr Paul Scott, Miss Katrena Stanhope, Mr Darren Towers for future generations. -

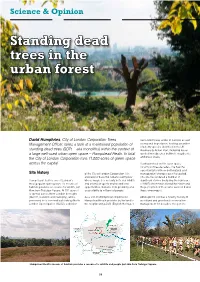

Standing Dead Trees in the Urban Forest

Science & Opinion Standing dead trees in the urban forest David Humphries, City of London Corporation Trees Kenwood Estate) and is of national as well Management Officer, takes a look at a maintained population of as regional importance, hosting a number of priority species identified in the UK standing dead trees (SDTs – aka monoliths) within the context of Biodiversity Action Plan, including lesser a large well-used urban open space – Hampstead Heath. In total spotted woodpecker, bullfinch, stag beetle the City of London Corporation runs 11,000 acres of green space and grass snake. across the capital. Having worked on this open space for almost three decades, I’ve had the opportunity to witness both natural and Site history of the City of London Corporation. It is management changes over that period. an island of beautiful ‘urban countryside’ The site has endured a number of Hampstead Heath is one of London’s whose magic lies not only in its rich wildlife significant storms (including the hurricane most popular open spaces. Its mosaic of and extensive sports and recreational of 1987) which have altered the Heath and habitats provides a resource for wildlife just opportunities, but also in its proximity and the perception of those who work on it and 6km from Trafalgar Square. At 791 acres it accessibility to millions of people. those who enjoy it. is spread across three London boroughs (Barnet, Camden and Haringey), and is As a Site of Metropolitan Importance, Although the site has a healthy history of preserved in its semi-natural state by North Hampstead Heath provides buffer land to woodland and grassland conservation London Open Spaces (NLOS), a division the neighbouring SSSI (English Heritage’s management for decades, the generic Hampstead Heath’s mosaic of habitats provides a resource for wildlife and people just 6km from Trafalgar Square. -

Simon Braidman's Bluebell Heath Project Notes 2014

REPORT FOR WORK PARTY SUNDAY 5TH JANUARY 2014 ATTENDEES: Simon Braidman, John Winter, Neville Day, Mo Farhand, John Bugler, Josh Kalms, Sue Kable and Rajinder Hayer 10.30am to 2.00pm Weather : clear then clouding over, light rain shower then dull dry 5 degrees centigrade TASK: Work along the top edge of Bluebell Heath, removing scrub saplings. Secondary tasks: 1)thinning scrub retention blocks by taking out lower branches 2) removing Holly from behind eastern end of bare earth bank 3) checking on whether the bare earth bank stops water flow across New Scrape 4) checking on flytips on Heathbourne Road and new really bad one on Common Road It was really great to see people after the long Christmas break. It is important to control the scrub level in Bluebell Heath. A lot of money has been spent re‐opening the clearing and the danger is the area, re‐scrubbing up. The most insidious threat are the masses of tiny scrub saplings which look like whole areas have had the Woodland Trust in, planting trees. Young scrub is an important habitat but it is superabundant and the quicker one can deal with them the better. The extremely heavy rainfall should make it easier to remove the whole tree. If only it was that easy. The reality is that these are not single trees often each flimsy stem is attached to others by an underground horizontal root. This root can be 2inches thick. Also there are living stumps with suckers growing from them sometimes with horizontal roots wrapped around them or even fused to them. -

Participative Approaches to Hedgerow Conservation

Open Research Online The Open University’s repository of research publications and other research outputs Participative Approaches to Hedgerow Conservation Thesis How to cite: Oreszczyn, Susan (1999). Participative Approaches to Hedgerow Conservation. PhD thesis The Open University. For guidance on citations see FAQs. c 1999 The Author Version: Version of Record Link(s) to article on publisher’s website: http://dx.doi.org/doi:10.21954/ou.ro.000075c6 Copyright and Moral Rights for the articles on this site are retained by the individual authors and/or other copyright owners. For more information on Open Research Online’s data policy on reuse of materials please consult the policies page. oro.open.ac.uk Participative Approaches to Hedgerow Conservation Susan Oreszczyn BSc (Hons) Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy The Systems Discipline, Faculty of Technology The Open University, United Kingdom. 28th September 1999 ABSTRACT This thesis demonstrates how systems ideas and grounded theory have been applied to provide a broader approach to researching hedgerows in England, drawing on the idea that holistic thinking brings together different people’s relationships with hedgerows and with each other concerning hedgerows. The cultural dimensions of hedgerows and their implications for future hedged landscapes were investigated through the collection and exploration of different groups perspectives - public, farmers and experts - in England and Canada, using a diversity of primary and secondary data sources. English hedgerows were important to all groups. Everyone liked hedged landscapes for aesthetic, visual and wildlife reasons. They were important for the way they break up the landscape; provide signs of the changing seasons; their sense of mystery and intimacy; their connections with the past and childhood memories. -

Sadlers Wood Annual Review 2020

Sadlers Wood Annual Review 2020 North Norfolk District Council 1/1/21 Contents Contents Contents ................................................................................................. 1 Introduction – Welcome to Sadlers Wood .......................................................... 2 Health Safety and Security ........................................................................... 5 Maintenance of Equipment, Buildings and Landscapes .......................................... 8 Environmental Management ........................................................................ 12 Biodiversity, Landscape and Heritage ............................................................ 14 Community Involvement ............................................................................ 17 Marketing and Communication .................................................................... 20 Conservation and Woodland Management Work Plan .......................................... 24 Site Risk Assessment ................................................................................... 0 Introduction – Welcome to Sadlers Wood Abstract This annual review outlines the management work, activities, projects, development and general progress made by North Norfolk District Council’s Countryside Service against Sadlers Wood Management Plan in 2020, and forms the basis of the authority’s application for continued Green Flag Award status. About Sadlers Wood and the surrounding open space lies at the eastern side of the market town of North Walsham -

Adaptation to Climate Change Sustainable Local Economies Abundant Wildlife Healthy Cities and Green Space for All

A living landscape A call to restore the UK’s battered ecosystems, for wildlife and people Adaptation to climate change Sustainable local economies Abundant wildlife Healthy cities and green space for all Updated with 100+ Living Landscape schemes So much of the UK now is packed with development Fenton/BBC Beatrice and wildlife is in retreat. There are many fine nature A LIVING LANDSCAPE reserves but our future must be to integrate human and natural communities and restore a better balance. This document lays out exciting and important new plans. Professor Aubrey Manning OBE President of The Wildlife Trusts Matthew Roberts. Cover picture: St Ives and the river Great Ouse, Cambridgshire, Dae Sasitorn/lastrefuge.co.uk Dae Cambridgshire, Ouse, Great river the and Ives St picture: Cover Roberts. Matthew Where will our water come from? When will our land use become truly sustainable? How can our environment adapt to climate change? What would it take to rebuild a wildlife-rich countryside? Why are so many people disconnected from nature? Priestcliffe Lees nature reserve, owned by Derbyshire Wildlife Trust: a treasure chest of local biodiversity. The Wildlife Trusts see such places as nodes from It’s time to think big which plants and animals can recolonise a recovering landscape To adapt to climate change, the UK’s wildlife will need to move Driven by local people and aspirations, The Wildlife Trusts play along ‘climate corridors’ up and down the country, or to shadier a leading role not just in developing the vision but in mustering slopes or cooler valleys. Wildlife has done it all before, after the the support that can allow communities to drive their own last ice age, but this time the change is faster and there are change. -

Partnership Meeting November 2019

Mendip Hills AONB Partnership Meeting March 2020 This was the presentation to be delivered to the Mendip Hills AONB Partnership on March 19th 2020. Additional text has been inserted to explain items further. The Mendip Hills AONB Nature Recovery Plan Paper C Tim Haselden Project Development Officer Mendip Hills AONB Unit Nature Recovery Plan Background: • The Glover Review of Designated Landscapes (2019) recommended that designated landscapes should have a revised purpose, focussing more on nature’s recovery: ‘Recover, conserve and enhance natural beauty, biodiversity and natural capital, and cultural heritage.’ • All AONBs signed up to ‘The Colchester Declaration’. Sets out AONB’s national strategy for change in order to redress declines in species and habitats within context of a wider response to Climate Change. • The Colchester Declaration states that all AONB Partnerships should produce and implement a ‘Nature Recovery Plan’ during 2020/21. Plans should contribute to national targets which state that by 2030: • at least 200,000ha of SSSIs in AONBs will be in favourable condition; • at least 100,000ha of wildlife-rich habitat outside of protected sites will have been created/restored; • at least 36,000ha of new woodland will have been planted or allowed to regenerate in AONBs following the principle of 'the right tree in the right place’. • Plans to be developed in partnership and look both within and outside of the AONB boundary, and should feed into Local Nature Recovery Strategies. Nature Recovery Plan The hierarchy of nature recovery planning: Nature Recovery Plan What we need to do: • Create an ambitious yet achievable and useable plan. -

Pretty Corner Woods Annual Review 2020

Pretty Corner Woods Annual Review 2020 North Norfolk District Council 1/1/21 Contents Contents Contents ................................................................................................. 1 Introduction – Welcome to Pretty Corner Woods ................................................. 2 Health Safety and Security ........................................................................... 6 Maintenance of Equipment, Buildings and Landscapes .......................................... 9 Environmental Management ........................................................................ 13 Biodiversity, Landscape and Heritage ............................................................ 15 Community Involvement ............................................................................ 17 Marketing and Communication .................................................................... 20 Conservation and Woodland Management Work Plan .......................................... 24 Site Risk Assessment ................................................................................... 0 Introduction – Welcome to Pretty Corner Woods Abstract This annual review outlines the management work, activities, projects, development and general progress made by North Norfolk District Council’s Countryside Service against Pretty Corner Woods Management Plan in 2020, and forms the basis of the authority’s application for continued Green Flag Award status. About Pretty Corner Woods, which has held Green Flag Status since 2013/14, forms part of a -

Grass Roots Magazine Winter 2018-2019

Grass Roots 1 The RHS Community Update Issue 36 • Winter 2018/2019 rhs.org.uk/get-involved Growing community Bloomers make a difference Grow a hedge Greening Grey Britain: RHS support Community orchard takes shape rhs.org.uk/get-involved 2 3 2 Welcome 3 Greening Grey Britain 2019 News 4 News 6 Growing as a force for good 8 Planting a hedge RHS / GUY HARROP 10 Reuse your garden sticks Welcome… 12 Urban orchards 14 Championing school ...to the winter issue of Grass Roots, the magazine for all community gardening groups, including Bloom and It’s Your Neighbourhood groups gardening and RHS Affiliated Societies. A very happy New Year to you all! We hope or changing tack in some way. Some of Left you’ve all enjoyed a well-deserved rest and your big ideas could possibly be helped into Volunteers and have had a chance to put your feet up after being, as part of RHS Greening Grey Britain students from Dunbar the hustle and bustle of the festive period. 2019. We are again looking for innovative Grammar School put the finishing touches Just as the buds that herald spring projects that bring different generations to a sensory garden appear in the depths of winter, many of together. Find out more on the next page. they helped create for your plans for the year ahead may have been people with dementia and their carers as germinating for some time. We are excited Best wishes and happy gardening, part of Greening Grey to see some of those plans take shape as RHS / JULIE HOWDEN Britain 2018.