Museum of the Cathedral of Chiusi

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Great Apostasy

The Great Apostasy R. J. M. I. By The Precious Blood of Jesus Christ; The Grace of the God of the Holy Catholic Church; The Mediation of the Blessed Virgin Mary, Our Lady of Good Counsel and Crusher of Heretics; The Protection of Saint Joseph, Patriarch of the Holy Family and Patron of the Holy Catholic Church; The Guidance of the Good Saint Anne, Mother of Mary and Grandmother of God; The Intercession of the Archangels Michael, Gabriel, and Raphael; The Intercession of All the Other Angels and Saints; and the Cooperation of Richard Joseph Michael Ibranyi To Jesus through Mary Júdica me, Deus, et discérne causam meam de gente non sancta: ab hómine iníquo, et dolóso érue me Ad Majorem Dei Gloriam 2 “I saw under the sun in the place of judgment wickedness, and in the place of justice iniquity.” (Ecclesiastes 3:16) “Woe to you, apostate children, saith the Lord, that you would take counsel, and not of me: and would begin a web, and not by my spirit, that you might add sin upon sin… Cry, cease not, lift up thy voice like a trumpet, and shew my people their wicked doings and the house of Jacob their sins… How is the faithful city, that was full of judgment, become a harlot?” (Isaias 30:1; 58:1; 1:21) “Therefore thus saith the Lord: Ask among the nations: Who hath heard such horrible things, as the virgin of Israel hath done to excess? My people have forgotten me, sacrificing in vain and stumbling in their way in ancient paths.” (Jeremias 18:13, 15) “And the word of the Lord came to me, saying: Son of man, say to her: Thou art a land that is unclean, and not rained upon in the day of wrath. -

Mediterranean Adventure Tours

Travel Mediterranean Adventure Tours: One by Land and Another by Sea icturing a get-away filled with Rome: Discover Historic Ancient intrigue, history and charm? Let the Ruins Psplendor of the Mediterranean direct your way to a dream vacation. Promising Your exciting tour begins in historic joyful memories to last a lifetime, there Rome, set amidst the glorious backdrop are two brilliant ways to tour the region, of ancient ruins. You’ll be greeted to a by land or by sea. Explore quaint villages, welcome dinner with wine at a specially dramatic cathedrals, ancient cities and selected local restaurant. Commence ruins, and historic sites. Travel through your sightseeing with a guided tour picturesque countryside and visit of The Colosseum of Rome, the large charming ports on emerald colored seas. amphitheater where deadly combat Delight your senses tasting regional of gladiators and wild animals took mouthwatering cuisine and enjoy place long ago. Built to hold 50,000 staying in luxurious accommodations. spectators, it was commissioned by observe the 2,000 year old red-granite Learn history on a fully-escorted seven- Emperor Vespasian and later completed Egyptian obelisk. Walk along the lines of day Italian land tour from Rome to by his son in AD 80. Just outside is travertine, as you stand facing St. Peter’s Venice or delight in a smorgasbord of the Arch of Constantine, a 25 m high Basilica, known as “the greatest of all excursions aboard a seven night Western monument built in AD 315 to mark Churches of Christendom.” This Late Mediterranean Cruise. Here are sample Constantine’s victory over Maxentius. -

On the Spiritual Matter of Art Curated by Bartolomeo Pietromarchi 17 October 2019 – 8 March 2020

on the spiritual matter of art curated by Bartolomeo Pietromarchi 17 October 2019 – 8 March 2020 JOHN ARMLEDER | MATILDE CASSANI | FRANCESCO CLEMENTE | ENZO CUCCHI | ELISABETTA DI MAGGIO | JIMMIE DURHAM | HARIS EPAMINONDA | HASSAN KHAN | KIMSOOJA | ABDOULAYE KONATÉ | VICTOR MAN | SHIRIN NESHAT | YOKO ONO | MICHAL ROVNER | REMO SALVADORI | TOMÁS SARACENO | SEAN SCULLY | JEREMY SHAW | NAMSAL SIEDLECKI with loans from: Vatican Museums | National Roman Museum | National Etruscan Museum - Villa Giulia | Capitoline Museums dedicated to Lea Mattarella www.maxxi.art #spiritualealMAXXI Rome, 16 October 2019. What does it mean today to talk about spirituality? Where does spirituality fit into a world dominated by a digital and technological culture and an ultra-deterministic mentality? Is there still a spiritual dimension underpinning the demands of art? In order to reflect on these and other questions MAXXI, the National Museum of XXI Century Arts, is bringing together a number of leading figures from the contemporary art scene in the major group show on the spiritual matter of art, strongly supported by the President of the Fondazione MAXXI Giovanna Melandri and curated by Bartolomeo Pietromarchi (from 17 October 2019 to 8 March 2020). Main partner Enel, which for the period of the exhibition is supporting the initiative Enel Tuesdays with a special ticket price reduction every Tuesday. Sponsor Inwit. on the spiritual matter of art is a project that investigates the issue of the spiritual through the lens of contemporary art and, at the same time, that of the ancient history of Rome. In a layout offering diverse possible paths, the exhibition features the works of 19 artists, leading names on the international scene from very different backgrounds and cultures. -

Ancient Cities: the Archaeology of Urban Life in the Ancient Near East, Egypt, Greece and Rome, Second Edition

ART 2311: Art and Architecture in Rome Fall 2016 A Days (Mondays and Wednesdays), 11:30am-1:00pm Aula Magna (plus site visits on some Wednesday afternoons) COURSE DESCRIPTION: This course gives students the unique opportunity to immerse themselves in the development of the city of Rome through a study of its art, architecture and urban transformation. It focuses on the major artistic and architectural movements occurring primarily in Italy (as well as their Greek antecedents) from roughly the 8th century BCE to the 20th century CE. In the study of each period we will strive to understand Rome’s artistic and architectural works within the contexts in which they were created. Our study of art, architecture and urban planning will therefore take into account the historical, political, social, religious and cultural contexts of the patrons, artists and viewers. Particular emphasis will be placed on ancient Greece and Rome, early Christianity, the Renaissance and the Baroque periods. We will also explore the reuse, borrowing and revival of ancient artistic and architectural themes in later periods. Instructor: Office Hours: Dr. Elizabeth Robinson Monday 4:00-6:00pm, or by appointment. [email protected] If you cannot make it to these office hours, Office: 560 please let me know and we can work out Office Phone: extension 560 another time to meet. REQUIRED TEXTS: (G) Gates, C.F. Ancient Cities: The archaeology of Urban Life in the Ancient Near East, Egypt, Greece and Rome, second edition. (Routledge, 2011). (C) Claridge, A. Rome. An Oxford Archaeological Guide. (Oxford 1998). (CP) Coursepack (consisting of several different readings assembled specifically for this course) ADDITIONAL READINGS: Occasionally texts, articles and handouts that will supplement the texts listed above may be assigned. -

Subscriber's Season Ticket to the National Etruscan

SUBSCRIBER'S SEASON TICKET TO THE NATIONAL ETRUSCAN MUSEUM AT VILLA GIULIA A unique, simple and economical way of living the museum experience as often as you like, getting to know and to familiarise in depth with one of the capital's most spectacular sites and museums. In the splendid setting of one of the most important Renaissance villas in Rome with its architecture, its frescoes and its waterworks, you will be able to explore the outstanding historical and artistic importance of the villa's archaeological collections, a "must see" for anyone wishing to discover the fascinating and intriguing civilisation of the Etruscans and of the other peoples who inhabited central Italy and its Tyrrhenian coast before the Romans. WHAT DOES IT OFFER unlimited access to the Museum , gardens and, when open, the exhibition area in Villa Poniatowski for the entire duration of the season ticket, from the date of purchase for a period of 3, 6 or 12 months. The opportunity, for the duration of your subscription, to attend all the free initiatives organised by the Museum (guided tours on specific themes, conventions, conferences, seminars, courses, exhibitions, book launches, documentary presentations, educational workshops, historical re-enactments, museum theatre activities, concerts, shows and so forth)* membership of a special mailing lit allowing interested subscribers to keep up to date on all the Museum's events and activities; participation free of charge in events reserved exclusively for season ticket holders (while places last; reservations are required; includes an invitation to exhibition inaugurations, guided tours with the Director, personalised in-depth exploration, dedicated events and so forth); 10% discount on purchases in the Museum bookshop; special rates for all fee-paying activites organised by the licencee (guided tours, educational workshops and so forth). -

Download All Beautiful Sites

1,800 Beautiful Places This booklet contains all the Principle Features and Honorable Mentions of 25 Cities at CitiesBeautiful.org. The beautiful places are organized alphabetically by city. Copyright © 2016 Gilbert H. Castle, III – Page 1 of 26 BEAUTIFUL MAP PRINCIPLE FEATURES HONORABLE MENTIONS FACET ICON Oude Kerk (Old Church); St. Nicholas (Sint- Portugese Synagoge, Nieuwe Kerk, Westerkerk, Bible Epiphany Nicolaaskerk); Our Lord in the Attic (Ons' Lieve Heer op Museum (Bijbels Museum) Solder) Rijksmuseum, Stedelijk Museum, Maritime Museum Hermitage Amsterdam; Central Library (Openbare Mentoring (Scheepvaartmuseum) Bibliotheek), Cobra Museum Royal Palace (Koninklijk Paleis), Concertgebouw, Music Self-Fulfillment Building on the IJ (Muziekgebouw aan 't IJ) Including Hôtel de Ville aka Stopera Bimhuis Especially Noteworthy Canals/Streets -- Herengracht, Elegance Brouwersgracht, Keizersgracht, Oude Schans, etc.; Municipal Theatre (Stadsschouwburg) Magna Plaza (Postkantoor); Blue Bridge (Blauwbrug) Red Light District (De Wallen), Skinny Bridge (Magere De Gooyer Windmill (Molen De Gooyer), Chess Originality Brug), Cinema Museum (Filmmuseum) aka Eye Film Square (Max Euweplein) Institute Musée des Tropiques aka Tropenmuseum; Van Gogh Museum, Museum Het Rembrandthuis, NEMO Revelation Photography Museums -- Photography Museum Science Center Amsterdam, Museum Huis voor Fotografie Marseille Principal Squares --Dam, Rembrandtplein, Leidseplein, Grandeur etc.; Central Station (Centraal Station); Maison de la Berlage's Stock Exchange (Beurs van -

Etruscan News 19

Volume 19 Winter 2017 Vulci - A year of excavation New treasures from the Necropolis of Poggio Mengarelli by Carlo Casi InnovativeInnovative TechnologiesTechnologies The inheritance of power: reveal the inscription King’s sceptres and the on the Stele di Vicchio infant princes of Spoleto, by P. Gregory Warden by P. Gregory Warden Umbria The Stele di Vicchio is beginning to by Joachim Weidig and Nicola Bruni reveal its secrets. Now securely identi- fied as a sacred text, it is the third 700 BC: Spoleto was the center of longest after the Liber Linteus and the Top, the “Tomba della Truccatrice,” her cosmetics still in jars at left. an Umbrian kingdom, as suggested by Capua Tile, and the earliest of the three, Bottom, a warrior’s iron and bronze short spear with a coiled handle. the new finds from the Orientalizing securely dated to the end of the 6th cen- necropolis of Piazza d’Armi that was tury BCE. It is also the only one of the It all started in January 2016 when even the heavy stone cap of the chamber partially excavated between 2008 and three with a precise archaeological con- the guards of the park, during the usual cover. The robbers were probably dis- 2011 by the Soprintendenza text, since it was placed in the founda- inspections, noticed a new hole made by turbed during their work by the frequent Archeologia dell’Umbria. The finds tions of the late Archaic temple at the grave robbers the night before. nightly rounds of the armed park guards, were processed and analysed by a team sanctuary of Poggio Colla (Vicchio di Strangely the clandestine excavation but they did have time to violate two of German and Italian researchers that Mugello, Firenze). -

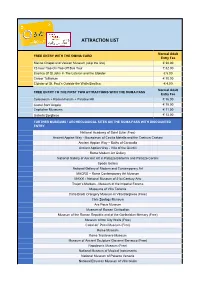

Attraction List

ATTRACTION LIST Normal Adult FREE ENTRY WITH THE OMNIA CARD Entry Fee Sistine Chapel and Vatican Museum (skip the line) € 30.00 72-hour Hop-On Hop-Off Bus Tour € 32.00 Basilica Of St.John In The Lateran and the Cloister € 5.00 Carcer Tullianum € 10.00 Cloister of St. Paul’s Outside the Walls Basilica € 4.00 Normal Adult FREE ENTRY TO THE FIRST TWO ATTRACTIONS WITH THE ROMA PASS Entry Fee Colosseum + Roman Forum + Palatine Hill € 16.00 Castel Sant’Angelo € 15.00 Capitoline Museums € 11.50 Galleria Borghese € 13.00 FURTHER MUSEUMS / ARCHEOLOGICAL SITES ON THE ROMA PASS WITH DISCOUNTED ENTRY National Academy of Saint Luke (Free) Ancient Appian Way - Mausoleum of Cecilia Metella and the Castrum Caetani Ancient Appian Way – Baths of Caracalla Ancient Appian Way - Villa of the Quintili Rome Modern Art Gallery National Gallery of Ancient Art in Palazzo Barberini and Palazzo Corsini Spada Gallery National Gallery of Modern and Contemporary Art MACRO – Rome Contemporary Art Museum MAXXI - National Museum of 21st Century Arts Trajan’s Markets - Museum of the Imperial Forums Museums of Villa Torlonia Carlo Bilotti Orangery Museum in Villa Borghese (Free) Civic Zoology Museum Ara Pacis Museum Museum of Roman Civilization Museum of the Roman Republic and of the Garibaldian Memory (Free) Museum of the City Walls (Free) Casal de’ Pazzi Museum (Free) Rome Museum Rome Trastevere Museum Museum of Ancient Sculpture Giovanni Barracco (Free) Napoleonic Museum (Free) National Museum of Musical Instruments National Museum of Palazzo Venezia National Etruscan -

The Eternal City: Rome for History Addicts! 7 Days

The Eternal City: Rome for History Addicts! 7 days Tour Description This 7 day, 6 night tour can be appreciated by anyone who loves history, young or old! Therefore, school groups, clubs, families or groups of friends can all likely extract ideas from the suggestions below. While the popular expression goes “all roads lead to Rome,” it could just as easily have been “Rome has a zillion monuments.” The magnitude of its cultural sites is so immense that it’s hard to wrap your head around it. That being said, even a history buff has to make choices in Rome! The itinerary below is based on a 6-night stay in Rome with many of the ancient capital’s must-see sights. While the attractions below are plentiful, we recommend striving for a pleasant pace; after all, it is your vacation. Should you want to extend your historical extravaganza by several days, we recommend you add the following ancient sites in Campania to your itinerary: Pompeii, Herculaneum and Paestum. Alternatively, if you don’t mind catching another flight, Sicily is a paradise for history fans and should absolutely be considered for a longer extension. Highlights Tour of iconic Colosseum Walking tour of central Rome’s top sights: Piazza Navona, the Pantheon, Campo de’ Fiori! Visit some of Italy’s best archaeological sites, including the Roman Forum and Ostia Antica Spend a morning in the Vatican Museums Explore the Emperor Hadrian’s astonishing villa Wander Rome’s ancient catacombs Sample Tour Itinerary Rome – 6 nights Day 1: Arrive in Rome Upon arrival to the Fiumicino Airport, you and your fellow history addicts will travel by private coach to your hotel in Rome, your epic base for the next six nights. -

Clst 334R: Introduction to Classical Archaeology in Rome and Italy

Loyola University Chicago John Felice Rome Center ClSt 334R: Introduction to Classical Archaeology in Rome and Italy Tuesdays 9:00 AM—12:00 PM JFRC + ON-SITE Instructor: Albert Prieto, M.Litt, PhD (Classics, History, Archaeology), [email protected] Office hours (faculty office): Tuesdays/Thursdays 3:00-3:30 and by appointment Introduction and Course Description What field allows you to study artifacts made by people 2000 years ago, read timeless literature, uncover and study ancient ruins in the open air while developing muscle tone and a tan, discover what ancient people ate and what diseases they had, reconstruct ancient religious beliefs, employ advanced digital technology to “see” what’s under the ground without digging, use a VR headset to immerse yourself in a reconstructed ancient setting, fly a drone, and ponder the Earth’s surface from the air or space? The answer is classical, or Greco-Roman, archaeology. This course introduces you to the surprisingly wide, often weird, and occasionally whimsical world of archaeology in Rome and Italy. We will start at the very beginning of the archaeological process, learning who the Romans were, how their society evolved historically, what kinds of tangible and intangible cultural assets they created, what happened to those assets after the inevitable collapse of the Roman Empire, and how centuries later people began the slow and steady process of reconstructing an accurate picture of a “lost” civilization from the many types of evidence left behind. Mention “archaeology,” and the first thing that invariably comes to mind is excavation: indeed, we will learn what modern archaeological excavation is (as opposed to digging for treasure) and what kinds of information it can retrieve for us. -

Reflecting on Mirrors

Reflecting on Mirrors: A Linguistic Analysis of Theonyms on Praenestine Hand Mirrors Hannelore Segers Promotor: Prof. Dr. Giovanbattista Galdi Lezers: Prof. Dr. De Temmerman en Dr. Wylin Masterproef voorgelegd aan de Faculteit Letteren en Wijsbegeerte Voor het behalen van de graad van Master in de taal- en letterkunde: Grieks-Latijn Academiejaar 2015-2016 Table of Contents Dankwoord .............................................................................................................................................. 3 0) List of abbreviations ........................................................................................................................ 4 1) Introduction ..................................................................................................................................... 5 a) Praenestine Mirrors: Some General Observations....................................................................... 5 b) The “city” of Praeneste ................................................................................................................ 7 c) The religious and economic importance of Praeneste ................................................................. 8 2) Methodology ................................................................................................................................. 11 a) Research Question ..................................................................................................................... 11 b) Historic Contextualization ........................................................................................................ -

The Original Documents Are Located in Box 16, Folder “6/3/75 - Rome” of the Sheila Weidenfeld Files at the Gerald R

The original documents are located in Box 16, folder “6/3/75 - Rome” of the Sheila Weidenfeld Files at the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library. Copyright Notice The copyright law of the United States (Title 17, United States Code) governs the making of photocopies or other reproductions of copyrighted material. Gerald R. Ford donated to the United States of America his copyrights in all of his unpublished writings in National Archives collections. Works prepared by U.S. Government employees as part of their official duties are in the public domain. The copyrights to materials written by other individuals or organizations are presumed to remain with them. If you think any of the information displayed in the PDF is subject to a valid copyright claim, please contact the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library. Digitized from Box 16 of the Sheila Weidenfeld Files at the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library 792 F TO C TATE WA HOC 1233 1 °"'I:::: N ,, I 0 II N ' I . ... ROME 7 480 PA S Ml TE HOUSE l'O, MS • · !? ENFELD E. • lt6~2: AO • E ~4SSIFY 11111~ TA, : ~ IP CFO D, GERALD R~) SJ 1 C I P E 10 NTIA~ VISIT REF& BRU SE 4532 UI INAl.E PAL.ACE U I A PA' ACE, TME FFtCIA~ RESIDENCE OF THE PR!S%D~NT !TA y, T ND 0 1 TH HIGHEST OF THE SEVEN HtL.~S OF ~OME, A CTENT OMA TtM , TH TEMPLES OF QUIRl US AND TME s E E ~oc T 0 ON THIS SITE. I THE CE TER OF THE PR!SENT QU?RINA~ IAZZA OR QUARE A~E ROMAN STATUES OF C~STOR ....