The Second Schleswig

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Findbuch Des Bestandes Abt. 320.6 Kreis Flensburg-Land 1867-1968

Findbuch des Bestandes Abt. 320.6 Kreis Flensburg-Land 1867-1968 von Hartmut Haase Veröffentlichungen des Landesarchivs Schleswig-Holstein Band 111 Findbuch des Bestandes Abt. 320.6 Kreis Flensburg-Land 1867-1968 von Hartmut Haase Hamburg University Press Verlag der Staats- und Universitätsbibliothek Hamburg Carl von Ossietzky Impressum Bibliografische Information der Deutschen Nationalbibliothek Die Deutsche Nationalbibliothek verzeichnet diese Publikation in der Deutschen Nationalbibliografie; detaillierte bibliografische Daten sind im Internet über https://portal.dnb.de/ abrufbar. ISSN 1864-9912 ISBN 3-978-943423-18-1 Online-Ausgabe Die Online-Ausgabe dieses Werkes ist eine Open-Access-Publikation und ist auf den Verlagswebseiten frei verfügbar. Die Deutsche Nationalbibliothek hat die Online-Ausgabe archiviert. Diese ist dauerhaft auf dem Archivserver der Deutschen Nationalbibliothek (https://portal.dnb.de/) verfügbar. DOI 10.15460/HUP.LASH.111.165 URN urn:nbn:de:gbv:18-3-1653 © 2017 Hamburg University Press, Verlag der Staats- und Universitätsbibliothek Hamburg Carl von Ossietzky, Deutschland Redaktion: Veronika Eisermann, Rainer Hering, Sven Schoen Produktion: Elbe-Werkstätten GmbH, Hamburg, Deutschland http://www.elbe-werkstaetten.de/ Gestaltung: Atelier Bokelmann, Schleswig INHALTSVERZEICHNIS Vorwort V Kreisverwaltung 1 Reichs- und Staatsangelegenheiten 1 Orden, Ehrenzeichen, Flaggen, Feierlichkeiten, Immediatgesuche 1 Wahlen zum Reichs-, Land- und Kreistag; Wahlen der Gemeindevertreter; Volksbegehren 2 Landkreisverwaltung 4 Abhaltung -

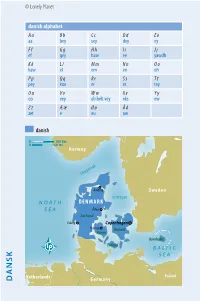

Danish Alphabet DENMARK Danish © Lonely Planet

© Lonely Planet danish alphabet A a B b C c D d E e aa bey sey dey ey F f G g H h I i J j ef gey haw ee yawdh K k L l M m N n O o kaw el em en oh P p Q q R r S s T t pey koo er es tey U u V v W w X x Y y oo vey do·belt vey eks ew Z z Æ æ Ø ø Å å zet e eu aw danish 0 100 km 0 60 mi Norway Skagerrak Aalborg Sweden Kattegat NORTH DENMARK SEA Århus Jutland Esberg Copenhagen Odense Zealand Funen Bornholm Lolland BALTIC SEA Poland Netherlands Germany DANSK DANSK DANISH dansk introduction What do the fairy tales of Hans Christian Andersen and the existentialist philosophy of Søren Kierkegaard have in common (apart from pondering the complexities of life and human character)? Danish (dansk dansk), of course – the language of the oldest European monarchy. Danish contributed to the English of today as a result of the Vi- king conquests of the British Isles in the form of numerous personal and place names, as well as many basic words. As a member of the Scandinavian or North Germanic language family, Danish is closely related to Swedish and Norwegian. It’s particularly close to one of the two official written forms of Norwegian, Bokmål – Danish was the ruling language in Norway between the 15th and 19th centuries, and was the base of this modern Norwegian literary language. In pronunciation, however, Danish differs considerably from both of its neighbours thanks to its softened consonants and often ‘swallowed’ sounds. -

Department of Regional Health Research Faculty of Health Sciences - University of Southern Denmark

Department of Regional Health Research Faculty of Health Sciences - University of Southern Denmark The focus of Department of Regional Health Research, Region of Southern Denmark, and Region Zealand is on cooperating to create the best possible conditions for research and education. 1 Successful research environments with open doors With just 11 years of history, Department of Regional Health Research (IRS) is a relatively “The research in IRS is aimed at the treatment new yet, already unconditional success of the person as a whole and at the more experiencing growth in number of employees, publications and co-operations across hospitals, common diseases” professional groups, institutions and national borders. University partner for regional innovations. IRS is based on accomplished hospitals professionals all working towards improving The research in IRS is directed towards the man’s health and creating value for patients, person as a whole and towards the more citizens and the community by means of synergy common diseases. IRS reaches out beyond the and high professional and ethical standards. traditional approach to research and focusses on We largely focus on the good working the interdisciplinary and intersectoral approach. environment, equal rights and job satisfaction IRS makes up the university partner and among our employees. We make sure constantly organisational frame for clinical research and to support the delicate balance between clinical education at hospitals in Region of Southern work, research and teaching. Denmark* and Region Zealand**. Supports research and education Many land registers – great IRS continues working towards strengthening geographical spread research and education and towards bringing the There is a great geographical spread between the department and the researchers closer together hospitals, but research environments and in the future. -

Text Planfeststellungsbeschluß BUND

Ministerium für Energiewende, Landwirtschaft, Umwelt, Natur und Digitalisierung des Landes Schleswig-Holstein - Amt für Planfeststellung Energie - uncodiert P L A N F E S T S T E L L U N G S Ä N D E R U N G S B E S C H L U S S betreffend der Änderung von Schutzgerüsten, Leitungsprovisorien, Zuwegungen, Arbeitsflächen, Anbindung des UW Schuby sowie Mastverschiebungen zum Planfeststellungsbeschluss vom 29.03.2018, Az.: AfPE L-667-PFV 380-kV-Ltg Audorf – Flensburg, für den Neubau der 380 kV-Freileitung Audorf - Flensburg Nr. 324 zwischen dem Umspannwerk Audorf und dem Umspannwerk Flensburg (Handewitt) sowie für den Rückbau der 220 kV-Freileitung Audorf – Flensburg Nr. 205 zwischen dem Umspannwerk Audorf und dem Umspannwerk Flensburg (Haurup) auf dem Gebiet derGemeinden Bollingstedt, Jübek, Lürschau, Schuby, Hüsby, Ellingstedt, Silberstedt (alle Amt Arensharde), Langstedt, Jerrishoe, Wanderup (alle Amt Eggebek), Osterrönfeld, Schülldorf, Rade, Ostenfeld, Schacht-Audorf (alle Amt Eiderkanal), Alt Duvenstedt, Rickert (alle Amt Fockbek), Owschlag, Borgstedt (alle Amt Hüttener Berge), Groß Rheide, Börm, Kropp, Tetenhusen, Klein Bennebek (alle Amt Kropp-Stapelholm), Oeversee, Tarp (alle Amt Oeversee) und der amtsfreien Gemeinde Handewitt - Kreise Rendsburg-Eckernförde und Schleswig-Flensburg – AfPE L-667-PFV 380-kV-Ltg Audorf - Flensburg Kiel, den 03.05.2019 - 2 / 45 - Inhaltsverzeichnis Planfeststellungsbeschluss 1. Festgestellte Freileitungsbaumaßnahme Seite 8 2. Maßgaben (Auflagen, Planänderungen, Erlaubnisse, Nebenbestimmungen) Seite 11 3. Enteignungrechtliche Vorwirkung Seite 23 4. Erledigung von Stellungnahmen und Einwendungen Seite 25 5. Zurückgewiesene Stellungnahmen und Einwendungen Seite 33 6. Plankorrekturen durch Blaueintragungen und Deckblätter (Hinweis) Seite 34 7. Zustellung (Auslegung) Seite 34 8. Sofortige Vollziehbarkeit Seite 35 9. -

Der Direktor Des Amtsgerichts Flensburg Geschäftszeichen: 234 E – 410 - Letzte Änderung: 01.03.2021 234 E - 399

Der Direktor des Amtsgerichts Flensburg Geschäftszeichen: 234 E – 410 - letzte Änderung: 01.03.2021 234 E - 399 - Geschäftsverteilung der Gerichtsvollzieherinnen und Gerichtsvollzieher des Amtsgerichts Flensburg ab 01.06.2021 1 Einteilung der Gerichtsvollzieherbezirke (ab 01.06.2021) Sprechstunden Bezirk Gerichtsvollzieher/in Anschrift und Vertretung Hirschbogen 31, 24963 Tarp Dienstag und Donnerstag 15:00 - 16:00 Uhr Obergerichtsvollzieher 1 Tel.: 04638/210424 Ronald Wohlert Fax: 04638/210425 Vertreter: Frau Johannsen [email protected] Fellerhye 13, 24977 Ringsberg Montag bis Mittwoch 15:00 - 16:00 Uhr Obergerichtsvollzieher Tel.: 04636/976127 2 Günter Müller 0151/61255257 Vertreter: Frau Weinrich-Mohr Fax: 04636/976128 [email protected] Am Schulwald 4, Mittwoch 14:00 - 15:00 Uhr 24837 Schleswig Freitag 09:00 - 10:00 Uhr Obergerichtsvollzieher 3 Oliver Vogt Tel.: 04621/9785736 Vertreter: Hr. Zimmermann; Fax: 04621/9785737 zweite Vertreterin im [email protected] Verhinderungsfall: Frau Dommel Mölken 66, 24866 Busdorf Mittwoch 11:00 - 12:00 Uhr Freitag 11:00 - 12:00 Uhr Obergerichtsvollzieher Tel.: 04621/21490 4 Jan Zimmermann 0152/03710900 Vertreter: Herr Vogt; Fax: 0461/89434 zweite Vertreterin im [email protected] Verhinderungsfall: Frau Dommel Am Moor 6, 24999 Wees Dienstag 11:00 - 12:00 Uhr im Amtsgericht Flensburg, A 107 Obergerichtsvollzieherin Tel.: 04631/4410099 Donnerstag 16:00 - 17:00 Uhr im 5 Roswitha Weinrich-Mohr 0151/50149803 Büro Am Moor 6, Wees Fax: 04631/62161 [email protected] Vertreter: -

The Royal Danish Naval Museu

THE ROYAL DANISH NAVAL MUSEU An introduction to the History of th , Royal Danish Na~ Ole lisberg Jensen Royal Danish Naval Museum Copenhagen 1994 THE ROYAL DANISH NAVAL MUSEUM An introduction to the History of the Royal Danish Navy. Ole Lisberg Jensen Copyright: Ole Lisberg Jensen, 1994 Printed in Denmark by The Royal Danish Naval Museum and Amager Centraltrykkeri ApS Published by the Royal Danish Naval Museum ISBN 87-89322-18-5 Frontispiece: c. Neumann 1859 Danish naval vessel at anchor off the British coast. One of the first naval artists, Neumann sailed with the fleet on a summer expedition. Title: The famous Dutch battle artist, Willem van der Velde (the elder), sailed with the Dutch relief fleet to Copenhagen in October 1658. Here we see one of his sketches, showing 5 Danish naval vessels led by TREFOLDIGHED. Copenhagen is in the background. Photo: archives of the Royal Danish Naval Museum. Back cover: The building housing the Royal Danish Naval Museum at Christianshavns Ksnel was originally a hospital wing of the Sekveesthuset. In 1988-89, the building was converted for the use of the Royal Danish Naval Museum with the aid ofa magnificent donation from »TheA.P. Moller and Mrs. Chastine Meersk. Mckinney Moller's Foundation for General Purposes". The building was constructed in 1780 by master builder Schotmann. When it was handed over to the Royal Danish Naval Museum, the building passed from the responsibility of the Ministry of Defence to that of the Ministry of Culture. PREFACE This catalogue is meant as a contribution to an understan War the models were evacuated to Frederiksborg Slot, and it ding ofthe chronology ofthe exhibits in the Royal Danish Na was not until 1957that the Royal Danish Naval Museum was val Museum. -

City-Apartment Am Südhafen Kappeln (Schlei)

City-Apartment am Südhafen Kappeln (Schlei) Anja und Bernhard Gummert Bahnhofsweg 14, 24376 Kappeln Schlei Tel.: 0151 – 438 107 12 [email protected] www.city-apartment-kappeln.de Ortsbeschreibung Die idyllische Hafenstadt Kappeln, gelegen an Schlei und Ostsee, ist ein staatlich anerkannter Erholungsort und unter anderem auch durch die ZDF-Serie "Der Landarzt" als Filmort „Deekelsen" bekannt. Kappeln liegt zwischen der Landeshauptstadt Kiel und der maritimen Hafenstadt Flensburg im wunderschönen Urlaubsland Schleswig-Holstein direkt an der Schlei. Eingebettet in einer sanften Hügellandschaft nahe der Ostsee liegt Kappeln in einer Urlaubsregion, die ideale Bedingungen für die unterschiedlichsten Aktivitäten an Land und zu Wasser bietet. Mit ihrem Yachthafen ist sie ein beliebtes Ausflugsziel nicht nur für Segler und Wassersportler. Mit ihren Sehenswürdigkeiten, dem reizvollen Hafen und der attraktiven Fußgängerzone lädt Kappeln zum Verweilen ein. Die bunte Geschäftswelt und die gemütlichen Restaurants und Cafés sorgen für einen angenehmen und abwechslungsreichen Aufenthalt. Regelmäßig verkehrende Ausflugsschiffe bringen Sie u.a. zur Lotseninsel Schleimünde, nach Arnis der kleinsten Stadt Deutschlands und an sehenswerte Stellen an der Schlei. Für Gäste, die das Strandleben bevorzugen, bietet sich der nur wenige Kilometer entfernten und sehr gepflegten Ostseestrand in Weidefeld an, der durch einen abgeteilten Strandabschnitt auch bei Surfern hoch im Kurs steht. Freizeitangebote in und um Kappeln Fahrradverleih direkt im Zentrum und am -

Common Reed for Thatching in Northern Germany: Estimating the Market Potential of Reed of Regional Origin

resources Article Common Reed for Thatching in Northern Germany: Estimating the Market Potential of Reed of Regional Origin Lea Becker, Sabine Wichmann and Volker Beckmann * Faculty of Law and Economics & Institute of Botany and Landscape Ecology, University of Greifswald, Soldmannstr. 15, D-17489 Greifswald, Germany; [email protected] (L.B.); [email protected] (S.W.) * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +49-3834-420-4122 Received: 1 October 2020; Accepted: 12 December 2020; Published: 16 December 2020 Abstract: Reed has a long tradition as locally available thatching material, but nowadays thatch is a globally traded commodity. Germany and other major importing countries such as the Netherlands, the United Kingdom, and Denmark rely on high import rates to meet the national consumption. This study aimed at providing a detailed picture of the thatching reed market in Northern Germany and at assessing the market potential for reed of regional origin. A written survey among all thatchers in Northern Germany was carried out in 2019, arriving at an effective sample of 47 out of 141 companies. The results revealed that for the responding companies the majority of the reed (59%) was used for rethatching roofs completely, 24% for newly constructed roofs, and 17% for roof repairs. Reed from Germany held a low share of 17% of the total consumption in 2018. Own reed harvesting was conducted by less than 9% of the responding companies and given up during the last decades by another 26%. The total market volume of reed for thatching in Northern Germany was estimated for 2018 with a 95% confidence interval at 3 0.8 million bundles of reed with a monetary value at ± sales prices of ¿11.6 2.8 million. -

CEMENT for BUILDING with AMBITION Aalborg Portland A/S Portland Aalborg Cover Photo: the Great Belt Bridge, Denmark

CEMENT FOR BUILDING WITH AMBITION Aalborg Portland A/S Cover photo: The Great Belt Bridge, Denmark. AALBORG Aalborg Portland Holding is owned by the Cementir Group, an inter- national supplier of cement and concrete. The Cementir Group’s PORTLAND head office is placed in Rome and the Group is listed on the Italian ONE OF THE LARGEST Stock Exchange in Milan. CEMENT PRODUCERS IN Cementir's global organization is THE NORDIC REGION divided into geographical regions, and Aalborg Portland A/S is included in the Nordic & Baltic region covering Aalborg Portland A/S has been a central pillar of the Northern Europe. business community in Denmark – and particularly North Jutland – for more than 125 years, with www.cementirholding.it major importance for employment, exports and development of industrial knowhow. Aalborg Portland is one of the largest producers of grey cement in the Nordic region and the world’s leading manufacturer of white cement. The company is at the forefront of energy-efficient production of high-quality cement at the plant in Aalborg. In addition to the factory in Aalborg, Aalborg Portland includes five sales subsidiaries in Iceland, Poland, France, Belgium and Russia. Aalborg Portland is part of Aalborg Portland Holding, which is the parent company of a number of cement and concrete companies in i.a. the Nordic countries, Belgium, USA, Turkey, Egypt, Malaysia and China. Additionally, the Group has acti vities within extraction and sales of aggregates (granite and gravel) and recycling of waste products. Read more on www.aalborgportlandholding.com, www.aalborgportland.dk and www.aalborgwhite.com. Data in this brochure is based on figures from 2017, unless otherwise stated. -

Coastal Living in Denmark

To change the color of the coloured box, right-click here and select Format Background, change the color as shown in the picture on the right. Coastal living in Denmark © Daniel Overbeck - VisitNordsjælland To change the color of the coloured box, right-click here and select Format Background, change the color as shown in the picture on the right. The land of endless beaches In Denmark, we look for a touch of magic in the ordinary, and we know that travel is more than ticking sights off a list. It’s about finding wonder in the things you see and the places you go. One of the wonders that we at VisitDenmark are particularly proud of is our nature. Denmark has wonderful beaches open to everyone, and nowhere in the nation are you ever more than 50km from the coast. s. 2 © Jill Christina Hansen To change the color of the coloured box, right-click here and select Format Background, change the color as shown in the picture on the right. Denmark and its regions Geography Travel distances Aalborg • The smallest of the Scandinavian • Copenhagen to Odense: Bornholm countries Under 2 hours by car • The southernmost of the • Odense to Aarhus: Under 2 Scandinavian countries hours by car • Only has a physical border with • Aarhus to Aalborg: Under 2 Germany hours by car • Denmark’s regions are: North, Mid, Jutland West and South Jutland, Funen, Aarhus Zealand, and North Zealand and Copenhagen Billund Facts Copenhagen • Video Introduction • Denmark’s currency is the Danish Kroner Odense • Tipping is not required Zealand • Most Danes speak fluent English Funen • Denmark is of the happiest countries in the world and Copenhagen is one of the world’s most liveable cities • Denmark is home of ‘Hygge’, New Nordic Cuisine, and LEGO® • Denmark is easily combined with other Nordic countries • Denmark is a safe country • Denmark is perfect for all types of travelers (family, romantic, nature, bicyclist dream, history/Vikings/Royalty) • Denmark has a population of 5.7 million people s. -

Southern Denmark Offers

SOUTHERN DENMARK SOUTHERN DENMARK OFFERS: \ An international work environment \ Professional challenges and opportunities \ A well-established life for the entire family \ Pillar industries: offshore, energy optimization, design, healthcare and technology SOUTHERN DENMARK IS A HIGHLY ATTRACTIVE INTERNATIONAL AREA AND PLACE TO WORK, WITH EASY SOUTHERN DENMARK OFFERS: ACCESS TO GREAT CITIES SUCH AS HAMBURG, KIEL AND \ Thousands of jobs COPENHAGEN. THE PROFESSIONAL CHALLENGES AND \ Great potential for career development OPPORTUNITIES ARE IDEAL WITH THESE FOUR GROWTH \ Excellent connections to the rest CENTRES IN THE REGION: ODENSE, SØNDERBORG, ESBJERG of the world \ Wonderful nature AND THE TRIANGLE REGION. \ Outstanding infrastructure Southern Denmarks industrial areas are particularly outstanding in the offshore industry, energy \ Plenty of social activities and optimization, and design and welfare technology. At the same time, we value that expats can live a opportunities complete life with their families. We have sensible living costs, great infrastructure, and plenty of social and professional associations for the entire family. LIVING IN DENMARK HIGH LIVING STANDARDS RELAXED CULTURE The standard of living is generally very Danish culture is relaxed and built on trust, high and people feel happy and safe. security and cooperation. Denmark shares THE first place as the least corrupt country in WELL-FUNCTIONING the world. HAPPINESS INFRASTRUCTURE INDEX The infrastructure is well-functioning, IT’S EASY meaning less time spent on commuting There are only a few compulsory regis- and transportation. trations you must obtain before and after you arrive in Denmark (the rules governing TOP-QUALITY SCHOOL SYSTEM these depend on your citizenship). Denmark is consistently ranked as one of the happiest nations in the world. -

Flensburg-Juni-2015-Data.Pdf

06/2015 · Juni Ausgabe Flensburg · 72324 ZWISCHEN NORD- UND OSTSEE Impulsgeber im Norden � Titelthema: Zukunftsmarkt Gesundheit � Wirtschaft im Gespräch: Hans-Jakob Tiessen � Feste Fehmarnbelt-Querung: Kanzlerin zeigt Entschlossenheit Für die raue Arbeitswelt geschaff en Robuste Begleiter für den Einsatz in der Logistik, auf dem Bau oder in der Produktion. Mörtelmatsch auf der Baustelle, Hitze im Stahlwerk, ein Sturz auf den Umgebung. Die Geräte verfügen über einen Staub- und Wasser schutz Boden: Trotz rauer Gegebenheiten ist die Samsung Ruggedized- gemäß IP671. Darüber hinaus sind sie nicht nur physisch für Extrem- Produktfamilie mit moderner Technik auch im Außendienst in ihrem einsätze gewappnet: Ausgestattet mit SAMSUNG KNOX™ schützt die Element. Gebaut um leistungs starke, vielseitige Performance und Ruggedized-Produktfamilie auch sensible Unternehmensdaten. sicheren Betrieb zu vereinen, bieten das GALAXY Tab Active, Testgerät- oder Bestellanfrage an: GALAXY Xcover 3 und Xcover 550 Unterstützung in nahezu jeder [email protected] 550 Das GALAXY Tab Active ist das Das GALAXY XCover 3 Nicht nur seine robuste Beschaff enheit erste IP671 zertifi zierte Tablet von ist optimal vor Stößen macht das Xcover 550 zu einem erstklas- Samsung, welches für den Einsatz in geschützt und erfüllt sogar sigen Begleiter unter fordernden Bedin- fordernden Business-Umgebungen den US-amerikanischen gungen, sondern durch seine kompakte gebaut wurde. Es wird mit einer spe- Militärstandard MIL-STD Größe mit geringem Gewicht ist es auch ziellen Hülle geliefert, die das Gerät 810G12. Auch Nässe und leicht zu verstauen. Zudem ermöglicht vor externen Einwirkungen schützt Dreck übersteht es dank eine solide Befestigungs-Öse am Rahmen und in vollem Umfang den US-ame- IP671-Zertiffi zierung des Featurephones, ein Trageband zu rikanischen Anti-Schock-Militärnor- souverän.