Thomas Carter 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2. the Climbing Gym Industry and Oslo Klatresenter As

Norwegian School of Economics Bergen, Spring 2021 Valuation of Oslo Klatresenter AS A fundamental analysis of a Norwegian climbing gym company Kristoffer Arne Adolfsen Supervisor: Tommy Stamland Master thesis, Economics and Business Administration, Financial Economics NORWEGIAN SCHOOL OF ECONOMICS This thesis was written as a part of the Master of Science in Economics and Business Administration at NHH. Please note that neither the institution nor the examiners are responsible − through the approval of this thesis − for the theories and methods used, or results and conclusions drawn in this work. 2 Abstract The main goal of this master thesis is to estimate the intrinsic value of one share in Oslo Klatresenter AS as of the 2nd of May 2021. The fundamental valuation technique of adjusted present value was selected as the preferred valuation method. In addition, a relative valuation was performed to supplement the primary fundamental valuation. This thesis found that the climbing gym market in Oslo is likely to enjoy a significant growth rate in the coming years, with a forecasted compound annual growth rate (CAGR) in sales volume of 6,76% from 2019 to 2033. From there, the market growth rate is assumed to have reached a steady-state of 3,50%. The period, however, starts with a reduced market size in 2020 and an expected low growth rate from 2020 to 2021 because of the Covid-19 pandemic. Based on this and an assumed new competing climbing gym opening at the beginning of 2026, OKS AS revenue is forecasted to grow with a CAGR of 4,60% from 2019 to 2033. -

Rock Climbing Inventory of NJ's State Parks and Forest

Allamuchy Mountain, Stephens State Park Rock Climbing Inventory of NJ’s State Parks and Forest Prepared by Access NJ Contents Photo Credit: Matt Carlardo www.climbnj.com June, 2006 CRI 2007 Access NJ Scope of Inventory I. Climbing Overview of New Jersey Introduction NJ’s Climbing Resource II. Rock-Climbing and Cragging: New Jersey Demographics NJ's Climbing Season Climbers and the Environment Tradition of Rock Climbing on the East Coast III. Climbing Resource Inventory C.R.I. Matrix of NJ State Lands Climbing Areas IV. Climbing Management Issues Awareness and Issues Bolts and Fixed Anchors Natural Resource Protection V. Appendix Types of Rock-Climbing (Definitions) Climbing Injury Patterns and Injury Epidemiology Protecting Raptor Sites at Climbing Areas Position Paper 003: Climbers Impact Climbers Warning Statement VI. End-Sheets NJ State Parks Adopt a Crag 2 www.climbnj.com CRI 2007 Access NJ Introduction In a State known for its beaches, meadowlands and malls, rock climbing is a well established year-round, outdoor, all weather recreational activity. Rock Climbing “cragging” (A rock-climbers' term for a cliff or group of cliffs, in any location, which is or may be suitable for climbing) in NJ is limited by access. Climbing access in NJ is constrained by topography, weather, the environment and other variables. Climbing encounters access issues . with private landowners, municipalities, State and Federal Governments, watershed authorities and other landowners and managers of the States natural resources. The motives and impacts of climbers are not distinct from hikers, bikers, nor others who use NJ's open space areas. Climbers like these others, seek urban escape, nature appreciation, wildlife observation, exercise and a variety of other enriching outcomes when we use the resources of the New Jersey’s State Parks and Forests (Steve Matous, Access Fund Director, March 2004). -

Tradclimbing+ the Positive Approach to Improving Your Climbing

TradCLIMBING+ The positive approach to improving your climbing Adrian Berry John Arran Uncredited photos by Adrian Berry Other photos as credited Illustrations by Ray Eckermann Printed by Clearpoint Colourprint Distributed by Cordee (www.cordee.co.uk) Published by ROCKFAX Ltd. December 2007 © ROCKFAX Ltd. 2007 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise without prior written permission of the copyright owner. A CIP catalogue record is available from the British Library. ISBN 978 1 873341 91 9 www.rockfax.com Cover: Adrian Berry on Cockblock (E5), Clogwyn y Grochan, Snowdonia, Wales. This page: Steve Ramsden on Fay (E4), Lower Sharpnose, Cornwall, England. Alex Barrows on the crux of Quietus (E2) Stanage Edge, The Peak District, England. Contents 3 Introduction (4) Starting Out (8) Tactics (190) Introduction A guide for newcomers showing the Tactics is about how to best use the skills various ways to get into trad climbing, the you already have to get those routes in important differences between climbing the bag and is a major part of the climbing Starting Out indoors and outside, plus an introduction game. to the key safety skills and terminology. The Mind (206) Gear (28) Gear For many climbers, the mind is the weakest A comprehensive look at the myriad of gear link. By taking a more positive approach available, with advice on what to buy to your mind can be turned from being a build up your climbing rack. weakness to being your best asset. -

Fatalities in Climbing - Boulder 2014

Fatalities in Climbing - Boulder 2014 V. Schöffl Evaluation of Injury and Fatality Risk in Rock and Ice Climbing: 2 One Move too Many Climbing: Injury Risk Study Type of climbing (geographical location) Injury rate (per 1000h) Injury severity (Bowie, Hunt et al. 1988) Traditional climbing, bouldering; some rock walls 100m high 37.5 a Majority of minor severity using (Yosemite Valley, CA, USA) ISS score <13; 5% ISS 13-75 (Schussmann, Lutz et al. Mountaineering and traditional climbing (Grand Tetons, WY, 0.56 for injuries; 013 for fatalities; 23% of the injuries were fatal 1990) USA) incidence 5.6 injuries/10000 h of (NACA 7) b mountaineering (Schöffl and Winkelmann Indoor climbing walls (Germany) 0.079 3 NACA 2; 1999) 1 NACA 3 (Wright, Royle et al. 2001) Overuse injuries in indoor climbing at World Championship NS NACA 1-2 b (Schöffl and Küpper 2006) Indoor competition climbing, World championships 3.1 16 NACA 1; 1 NACA 2 1 NACA 3 No fatality (Gerdes, Hafner et al. 2006) Rock climbing NS NS 20% no injury; 60% NACA I; 20% >NACA I b (Schöffl, Schöffl et al. 2009) Ice climbing (international) 4.07 for NACA I-III 2.87/1000h NACA I, 1.2/1000h NACA II & III None > NACA III (Nelson and McKenzie 2009) Rock climbing injuries, indoor and outdoor (NS) Measures of participation and frequency of Mostly NACA I-IIb, 11.3% exposure to rock climbing are not hospitalization specified (Backe S 2009) Indoor and outdoor climbing activities 4.2 (overuse syndromes accounting for NS 93% of injuries) Neuhhof / Schöffl (2011) Acute Sport Climbing injuries (Europe) 0.2 Mostly minor severity Schöffl et al. -

Larry Land Climbing Topo

90 BOWMAN AREA CRAGS BOWMAN AREA CRAGS 91 Bowman Dam 21 18 17 14 21 19 21 20 16 1 15 4 2 23 13 22 3 12 Small 5 11 Cave 7 6 10 8 Approach 9 Larry Land N39° 26.648' W120° 39.256' Toprope the plumb line below the anchor on Gary Land. 7 Larry Land 70' 5.11c dam. When the road ends, follow a rough walkway up the right 4 Gary Land 45' 5.10d Mike Carville, Gary Allan, Josh Horniak, Spring 2008. Exposure: South. Afternoon sun, no shade. side of the drainage, then cross the drainage via a concrete Mike Carville, Josh Horniak, Fall 2008. 9 bolts. LO. Elevation: 5,480' spillway. After 40' cross back to the south side of the spillway 7 bolts. LO. A crag classic, this route is typified by athletic climbing on good Summary: Sport climbing. and ascend a low-angle rock slab to reach the large, concrete 25' left of Yuba Blue, this route begins on a short corner (crux), holds. Begin climbing the steep, broken rock immediately right Approach: 5 minutes, 0.2 miles. concourse directly below the dam. Reach the wall by ascend- then continues ascending the wall with more-moderate diffi- of the central cave. Trend generally left while aiming for the left Immediately below the Lake Bowman dam lies the south-fac- ing the talus field to the right of some large boulders. culty (5.9). Trend rightward from the mid-route corner. end of a shallow roof feature located above a gold-tinged slab. -

Layout 1 Copy

STACK ROCK 2020 An illustrated guide to sea stack climbing in the UK & Ireland - Old Harry - - Old Man of Stoer - - Am Buachaille - - The Maiden - - The Old Man of Hoy - - over 200 more - Edition I - version 1 - 13th March 1994. Web Edition - version 1 - December 1996. Web Edition - version 2 - January 1998. Edition 2 - version 3 - January 2002. Edition 3 - version 1 - May 2019. Edition 4 - version 1 - January 2020. Compiler Chris Mellor, 4 Barnfield Avenue, Shirley, Croydon, Surrey, CR0 8SE. Tel: 0208 662 1176 – E-mail: [email protected]. Send in amendments, corrections and queries by e-mail. ISBN - 1-899098-05-4 Acknowledgements Denis Crampton for enduring several discussions in which the concept of this book was developed. Also Duncan Hornby for information on Dorset’s Old Harry stacks and Mick Fowler for much help with some of his southern and northern stack attacks. Mike Vetterlein contributed indirectly as have Rick Cummins of Rock Addiction, Rab Anderson and Bruce Kerr. Andy Long from Lerwick, Shetland. has contributed directly with a lot of the hard information about Shetland. Thanks are also due to Margaret of the Alpine Club library for assistance in looking up old journals. In late 1996 Ben Linton, Ed Lynch-Bell and Ian Brodrick undertook the mammoth scanning and OCR exercise needed to transfer the paper text back into computer form after the original electronic version was lost in a disk crash. This was done in order to create a world-wide web version of the guide. Mike Caine of the Manx Fell and Rock Club then helped with route information from his Manx climbing web site. -

White Mountain National Forest Pemigewasset Ranger District November 2015

RUMNEY ROCKS CLIMBING MANAGEMENT PLAN White Mountain National Forest Pemigewasset Ranger District November 2015 Introduction The Rumney Rocks Climbing Area encompasses approximately 150 acres on the south-facing slopes of Rattlesnake Mountain on the White Mountain National Forest (WMNF) in Rumney, New Hampshire. Scattered across these slopes are approximately 28 rock faces known by the climbing community as "crags." Rumney Rocks is a nationally renowned sport climbing area with a long and rich climbing history dating back to the 1960s. This unique area provides climbing opportunities for those new to the sport as well as for some of the best sport climbers in the country. The consistent and substantial involvement of the climbing community in protection and management of this area is a testament to the value and importance of Rumney Rocks. This area has seen a dramatic increase in use in the last twenty years; there were 48 published climbing routes at Rumney Rocks in Ed Webster's 1987 guidebook Rock Climbs in the White Mountains of New Hampshire and are over 480 documented routes today. In 2014 an estimated 646 routes, 230 boulder problems and numerous ice routes have been documented at Rumney. The White Mountain National Forest Management Plan states that when climbing issues are "no longer effectively addressed" by application of Forest Plan standards and guidelines, "site specific climbing management plans should be developed." To address the issues and concerns regarding increased use in this area, the Forest Service developed the Rumney Rocks Climbing Management Plan (CMP) in 2008. Not only was this the first CMP on the White Mountain National Forest, it was the first standalone CMP for the US Forest Service. -

Victorian Climbing Management Guidelines

Victorian Climbing Management Guidelines Compiled for the Victorian Climbing Community Revision: V04 Published: 15 Sept 2020 1 Contributing Authors: Matthew Brooks - content manager and writer Ashlee Hendy Leigh Hopkinson Kevin Lindorff Aaron Lowndes Phil Neville Matthew Tait Glenn Tempest Mike Tomkins Steven Wilson Endorsed by: Crag Stewards Victoria VICTORIAN CLIMBING MANAGEMENT GUIDELINES V04 15 SEPTEMBER 2020 2 Foreword - Consultation Process for The Victorian Climbing Management Guidelines The need for a process for the Victorian climbing community to discuss widely about best rock-climbing practices and how these can maximise safety and minimise impacts of crag environments has long been recognised. Discussions on these themes have been on-going in the local Victorian and wider Australian climbing communities for many decades. These discussions highlighted a need to broaden the ways for climbers to build collaborative relationships with Traditional Owners and land managers. Over the years, a number of endeavours to build and strengthen such relationships have been undertaken; Victorian climbers have been involved, for example, in a variety of collaborative environmental stewardship projects with Land Managers and Traditional Owners over the last two decades in particular, albeit in an ad hoc manner, as need for such projects have become apparent. The recent widespread climbing bans in the Grampians / Gariwerd have re-energised such discussions and provided a catalyst for reflection on the impacts of climbing, whether inadvertent or intentional, negative or positive. This has focussed considerations of how negative impacts on the environment or cultural heritage can be avoided or minimised and on those climbing practices that are most appropriate, respectful and environmentally sustainable. -

4º Eso Physical Educacion

4º ESO - PE Workbook - IES Joan Miró – Physical Education Department CLIMBING 4º ESO PHYSICAL EDUCACION 1 4º ESO - PE Workbook - IES Joan Miró – Physical Education Department 1. CLIMBING 1.1. INTRODUCTION Climbing is the activity of using one's hands and feet (or indeed any other part of the body) to ascend a steep object. It is done both for recreation (to reach an inaccessible place, or for its own enjoyment) and professionally, as part of activities such as maintenance of a structure, or military operations. 2. ROCK-CLIMBING EQUIPMENT 2.1. ROPE Ropes used for climbing can be divided into two classes: dynamic ropes and low elongation ropes (static ropes). Dynamic ropes are designed to absorb the energy of a falling climber, and are usually used as belaying ropes. When a climber falls, the rope stretches, reducing the maximum force experienced by the climber and the equipment. Low elongation or static ropes stretch much less, and are usually used in anchoring systems. They are also used for abseiling (rappeling) and as fixed ropes climbed with ascenders. 2.2. CARABINERS Carabiners are metal loops with spring-loaded gates (openings), used as connectors. Once made primarily from steel, almost all carabiners for recreational climbing are made from a lightweight aluminum alloy. Steel carabiners are harder wearing, but much heavier and often used by instructors when working with groups. 2.3. QUICKDRAWS Quickdraws (often referred to as "draws") are used by climbers to connect ropes to bolt anchors, or to other traditional protection, allowing the rope move through the anchoring system with minimal friction. -

Anchors BODY04

Part 2 of 3 Why Fixed Anchors Are Needed ecreational rock climbing, ranging from traditional mountain- Sport climbing evolved through technological advances in eering to sport climbing, is increasing on national forests. climbing equipment. This type of climbing is usually done on a RR Recreational rock climbing has occurred on national forests single pitch, or face, and often relies on bolts. Sport climbing for many years, inside and outside of designated wilderness. differs from traditional rock climbing where more strategic, and Rock climbers routinely use fixed anchors to assist them in sometimes horizontal, movement is favored over a quick vertical their climb and to help them navigate dangerous terrain safely. climb and descent. Bolted routes increase the margin of safety The safest, most common reliable fixed anchor is an expansion for climbers. bolt, a small steel bolt placed in a hole that has been drilled into the rock (figure 1). Frequently, a “hanger” is attached to an Traditional rock climbing uses removable protection such as expansion bolt to accommodate a carabiner or sling (figure 2). nuts, stoppers, or cam devices, placed into a crack of the rock formation (figure 3). Traditional rock-climbing protection devices require sound judgment for placements. These protection devices are rated for strength in pounds or metric units of force called kilonewtons. A kilonewton rating measures the amount of force that would break a piece of equipment during a fall. Even traditional climbing requires bolts to be placed at the top of a vertical crag for rappelling if there is no other way of descending. Figure 1—An expansion bolt is placed in a drilled hole into the rock. -

Public Chat from 02.25.21 Community Forum on Winter Climbing

17:59:29 From Sarah Garlick to Everyone : Welcome! 18:11:07 From Sarah Garlick to Everyone : Statement https://www.nhledges.org/projects-campaigns/ Comment Form https://tinyurl.com/FriendsComment Thank you to the many climbers who have helped shape the initial winter practices statement and the gathering tonight, including: Nick Aiello-Popeo Sam Bendroth Liam Byrer Peter Doucette Justin Guarino Meg Hoffer Mike Morin Jon Nicolodi Brian O'leary Zac St. Jules Jim Surette Mark Synnott Michael Wejchert Freddie Wilkinson Kurt Winkler 18:15:52 From Sarah Garlick to Everyone : Sign up for Friends of the Ledges email list: https://www.nhledges.org/get-involved/ 18:15:58 From Sarah Garlick to Everyone : Indigenous New Hampshire Collaborative Collective: https://indigenousnh.com/ 18:21:52 From Sarah Garlick to Everyone : I love seeing all your faces - thank you all for being here! 18:23:34 From Bruce Franks to Everyone : Thanks a lot Sarah, I appreciate all the work you do and the work to get this event tonight working. 18:32:19 From Justin Preisendorfer to Everyone : Way to power your way through Bayard! 18:46:06 From Sarah Garlick to Everyone : https://rockandice.com/opinion/style- matters-cryokinesis-and-the-new-ethics-in-new-hampshire-winter-climbing/ 18:50:48 From nickaiello to Everyone : Think past what I want to do at a moment? How quaint. 18:53:14 From Sarah Garlick to Everyone : But isn’t one of the problems that you don’t think you’re doing any “real” damage when you head up on a piece of granite? One of the problems is that the impact is really tiny… but it adds up…. -

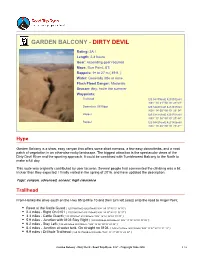

Garden Balcony - Dirty Devil

GARDEN BALCONY - DIRTY DEVIL Rating: 3A I Length: 2-4 hours Gear: Ascending gear required. Maps: Burr Point, UT; Rappels: 1+ to 27 m ( 89 ft. ) Water: Generally little or none. Flash Flood Danger: Moderate Season: Any, hot in the summer Waypoints: Trailhead 12S 543796mE 4230932mN N38° 13' 31" W110° 29' 59" Downclimb Off Ridge 12S 544401mE 4231837mN N38° 14' 00" W110° 29' 34" Rappel 12S 544143mE 4231701mN N38° 13' 56" W110° 29' 44" Rappel 12S 544216mE 4231406mN N38° 13' 46" W110° 29' 41" Hype Garden Balcony is a short, easy canyon that offers some short narrows, a few easy downclimbs, and a neat patch of vegetation in an otherwise rocky landscape. The biggest attraction is the spectacular views of the Dirty Devil River and the sporting approach. It could be combined with Tumbleweed Balcony to the North to make a full day. This route was originally contributed by user tacovan. Several people had commented the climbing was a bit trickier than they expected. I finally visited in the spring of 2016, and have updated the description. Tags: canyon, advanced, access: high clearance Trailhead From Hanksville drive south on the Hwy 95 to Mile 10 and then turn left (east) onto the road to Angel Point. Reset at the Cattle Guard ( 12S 530870mE 4232076mN / N38° 14' 10" W110° 38' 50" ) 2.4 miles - Right On 0101 ( 12S 534101mE 4232785mN / N38° 14' 33" W110° 36' 37" ) 3.3 miles - Cattle Guard ( 12S 535083mE 4231909mN / N38° 14' 04" W110° 35' 57" ) 5.9 miles - Junction with 0103 Stay Right ( 12S 538059mE 4230240mN / N38° 13' 10" W110° 33' 55" ) 6.2 miles - Stay Left ( 12S 538464mE 4230109mN / N38° 13' 05" W110° 33' 38" ) 8.4 miles - Junction at water tank.