Analysis of Different Usage Between “Kan” (Seeing) and “Jian” (Meeting)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Annual Report 2019 Mobility

(a joint stock limited company incorporated in the People’s Republic of China with limited liability) Stock Code: 1766 Annual Report Annual Report 2019 Mobility 2019 for Future Connection Important 1 The Board and the Supervisory Committee of the Company and its Directors, Supervisors and Senior Management warrant that there are no false representations, misleading statements contained in or material omissions from this annual report and they will assume joint and several legal liabilities for the truthfulness, accuracy and completeness of the contents disclosed herein. 2 This report has been considered and approved at the seventeenth meeting of the second session of the Board of the Company. All Directors attended the Board meeting. 3 Deloitte Touche Tohmatsu CPA LLP has issued standard unqualified audit report for the Company’s financial statements prepared under the China Accounting Standards for Business Enterprises in accordance with PRC Auditing Standards. 4 Liu Hualong, the Chairman of the Company, Li Zheng, the Chief Financial Officer and Wang Jian, the head of the Accounting Department (person in charge of accounting affairs) warrant the truthfulness, accuracy and completeness of the financial statements in this annual report. 5 Statement for the risks involved in the forward-looking statements: this report contains forward-looking statements that involve future plans and development strategies which do not constitute a substantive commitment by the Company to investors. Investors should be aware of the investment risks. 6 The Company has proposed to distribute a cash dividend of RMB0.15 (tax inclusive) per share to all Shareholders based on the total share capital of the Company of 28,698,864,088 shares as at 31 December 2019. -

OA Is the Most Common Cause of Joint Pain and Disability in the Elderly

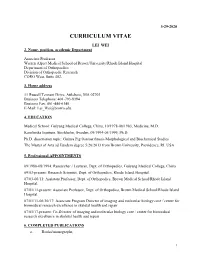

3-29-2020 CURRICULUM VITAE LEI WEI 2. Name, position, academic Department Associate Professor Warren Alpert Medical School of Brown University/Rhode Island Hospital Department of Orthopaedics Division of Orthopaedic Research CORO West, Suite 402, 3. Home address 11 Russell Tennant Drive, Attleboro, MA 02703 Business Telephone: 401-793-8384 Business Fax: 401-444-6140 E-Mail: [email protected] 4. EDUCATION Medical School: Guiyang Medical College, China, 10/1978-08/1983, Medicine, M.D. Karolinska Institute, Stockholm, Sweden, 09/1994-05/1999, Ph.D. Ph.D. dissertation topic: Guinea Pig Osteoarthrosis-Morphological and Biochemical Studies The Master of Arts ad Eundem degree 5/26/2013 from Brown University, Providence, RI. USA 5. Professional APPOINTMENTS 09/1988-08/1994: Researcher / Lecturer, Dept. of Orthopedics, Guiyang Medical College, China 09/03-present: Research Scientist, Dept. of Orthopedics, Rhode Island Hospital. 07/03-06/11: Assistant Professor, Dept. of Orthopedics, Brown Medical School/Rhode Island Hospital. 07/01/11-present: Associate Professor, Dept. of Orthopedics, Brown Medical School/Rhode Island Hospital. 07/01/11-06/30/17: Associate Program Director of imaging and molecular biology core / center for biomedical research excellence in skeletal health and repair 07/01/17-present: Co-Director of imaging and molecular biology core / center for biomedical research excellence in skeletal health and repair 6. COMPLETED PUBLICATIONS a. Books/monographs; 1 b. Chapters in books; Chen, Q., Lei, W., Wang, Z., Sun, X., Luo, J., and Yang, X. Endochondral bone formation and extracellular matrix, Current Topics in Bone Biology, 145-162, Deng, H., and Liu, Y. (Eds) World Scientific Publishing Co. -

THE INDIVIDUAL and the STATE: STORIES of ASSASSINS in EARLY IMPERIAL CHINA by Fangzhi Xu

THE INDIVIDUAL AND THE STATE: STORIES OF ASSASSINS IN EARLY IMPERIAL CHINA by Fangzhi Xu ____________________________ Copyright © Fangzhi Xu 2019 A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of the DEPARTMENT OF EAST ASIAN STUDIES In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS In the Graduate College THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA 2019 Xu 2 Xu 3 Contents Abstract ...................................................................................................................................... 4 Introduction ................................................................................................................................ 5 Chapter 1: Concepts Related to Assassins ............................................................................... 12 Chapter 2: Zhuan Zhu .............................................................................................................. 17 Chapter 3: Jing Ke ................................................................................................................... 42 Chapter 4: Assassins as Exempla ............................................................................................. 88 Conclusion ............................................................................................................................... 96 Bibliography .......................................................................................................................... 100 Xu 4 Abstract In my thesis I try to give a new reading about the stories of assassins in the -

CHINESE ARTISTS Pinyin-Wade-Giles Concordance Wade-Giles Romanization of Artist's Name Dates R Pinyin Romanization of Artist's

CHINESE ARTISTS Pinyin-Wade-Giles Concordance Wade-Giles Romanization of Artist's name ❍ Dates ❍ Pinyin Romanization of Artist's name Artists are listed alphabetically by Wade-Giles. This list is not comprehensive; it reflects the catalogue of visual resource materials offered by AAPD. Searches are possible in either form of Romanization. To search for a specific artist, use the find mode (under Edit) from the pull-down menu. Lady Ai-lien ❍ (late 19th c.) ❍ Lady Ailian Cha Shih-piao ❍ (1615-1698) ❍ Zha Shibiao Chai Ta-K'un ❍ (d.1804) ❍ Zhai Dakun Chan Ching-feng ❍ (1520-1602) ❍ Zhan Jingfeng Chang Feng ❍ (active ca.1636-1662) ❍ Zhang Feng Chang Feng-i ❍ (1527-1613) ❍ Zhang Fengyi Chang Fu ❍ (1546-1631) ❍ Zhang Fu Chang Jui-t'u ❍ (1570-1641) ❍ Zhang Ruitu Chang Jo-ai ❍ (1713-1746) ❍ Zhang Ruoai Chang Jo-ch'eng ❍ (1722-1770) ❍ Zhang Ruocheng Chang Ning ❍ (1427-ca.1495) ❍ Zhang Ning Chang P'ei-tun ❍ (1772-1842) ❍ Zhang Peitun Chang Pi ❍ (1425-1487) ❍ Zhang Bi Chang Ta-ch'ien [Chang Dai-chien] ❍ (1899-1983) ❍ Zhang Daqian Chang Tao-wu ❍ (active late 18th c.) ❍ Zhang Daowu Chang Wu ❍ (active ca.1360) ❍ Zhang Wu Chang Yü [Chang T'ien-yu] ❍ (1283-1350, Yüan Dynasty) ❍ Zhang Yu [Zhang Tianyu] Chang Yü ❍ (1333-1385, Yüan Dynasty) ❍ Zhang Yu Chang Yu ❍ (active 15th c., Ming Dynasty) ❍ Zhang You Chang Yü-ts'ai ❍ (died 1316) ❍ Zhang Yucai Chao Chung ❍ (active 2nd half 14th c.) ❍ Zhao Zhong Chao Kuang-fu ❍ (active ca. 960-975) ❍ Zhao Guangfu Chao Ch'i ❍ (active ca.1488-1505) ❍ Zhao Qi Chao Lin ❍ (14th century) ❍ Zhao Lin Chao Ling-jang [Chao Ta-nien] ❍ (active ca. -

King Wen's Tower

King Wen’s Tower Game in Progress by Emily Care Boss Black & Green Games L 2014 GM Checklist • Welcome everyone • Second Round (and on until 1 Kingdom Left) • Overview of Game Intrigue Scene: GM choose Kingdom Warring States Period Scenario Rules Tower Phase Token hand off (all Kingdoms) Choose Kingdom Tile • Setup Conquering Scene Map and Kingdom Sheets Kingdom Player choose: Battle or Surrender Players choose Kingdoms Questions Tokens, Cards, Tiles and Reference sheets • Last Kingdom • Introduction Optonal Intrigue Scene: War Council of Qin Last Kingdom Player: Ying Zheng Kingdom Descriptions Tower Phase Conquering Scene for unplayed No Tokens Kingdoms (1 question each) Play Kingdom Tile Conquering Scene • First Round: Battle or Surrender Questions Intrigue Scene Horizontal & Vertical Alliances • Debriefing Tower Phase King Wen Sequence Token hand off (GM breaks ties) Find Kingdom Tile Hexagram Choose Kingdom Tile Answer Question Conquering Scene History Kingdom Player chose: Share historical timeline Battle or Surrender Questions Materials • Game rules • Tokens (7) use counters, coins or stones, etc. Warring States Map • • Kingdom Tiles (12) Two per Kingdom, cut out GM Reference Sheets (pp. 13 - 16) • • Qin Agent Cards (12) cut out Kingdom Sheets (7) One per Kingdom • • King Wen Sequence Table - Questions Player Reference (7) Hundred Schools, Stratagems • • Blank paper - name cards for Intrigue Scenes 2 Table of Contents GM Checklist. 2 About the Game. 4 Scenario Rules. 5 Early Chinese History. 8 Hundred Schools of Thought. 9 Stratagems. .10 Map of the Seven Kingdoms. 11 Kingdoms of the Late Warring States Period. .12 Intrigue Scene Summaries. .13 Kingdom Summary Sheets: Qin (GM). 15 GM Master list of Battle & Surrender Scenes. -

Acknowledgements to Reviewers

Acta Pharmacologica Sinica (2020) 41: i–iv © 2020 CPS and SIMM All rights reserved 1671-4083/20 www.nature.com/aps Acknowledgements to Reviewers The Editorial Board of the Acta Pharmacologica Sinica wishes to thank the following scientists for their unique contribution to this journal in reviewing the papers from November 1, 2019 to October 31, 2020 (including papers published and rejected). AA, Ji-ye (Nanjing) CHEN, Hong-guang (Tianjin) DAI, Hou-yong (Nanjing) ACCORNERO, Federica (Columbus) CHEN, Hou-zao (Beijing) DAI, Mei (Cincinnati) ALOBAID, Abdulaziz S (Riyadh) CHEN, Hsin-Hung (Tainan) DAI, Min (Hefei) ARAYA, Jun (Minato-ku) CHEN, Jing (Jining) DAI, Xiao-yan (Guangzhou) ARIGA, Hiroyoshi (Sapporo) CHEN, Jing (Shanghai) DAI, Yue (Nanjing) ARIYOSHI, Wataru (Kitakyushu) CHEN, Jun (Shanghai) DANG, Yong-jun (Shanghai) ASTOLFI, Andrea (Perugia) CHEN, Jun (Tianjin) DAS, Archita (Augusta) BAI, Li-Yuan (Taichung) CHEN, Kun-qi (Suzhou) DAY, Regina M (Bethesda) BAI, Xiaowen (Milwaukee) CHEN, Nai-hong (Beijing) DE GEEST, Bruno (Ghent) BAN, Tao (Harbin) CHEN, Peng (Guangzhou) DENG, Xian-ming (Xiamen) BANERJEE, D (Chandigarh) CHEN, Qiu-yun (Zhenjiang) DENG, Xiao-yong (Shanghai) BAO, Jin-ku (Chengdu) CHEN, Rui-zhen (Shanghai) DENG, Xu-ming (Changchun) BAO, Mei-hua (Changsha) CHEN, Shuai-shuai (Linhai) DENG, Yi-lun (San Antonio) BAO, Yu-qian (Shanghai) CHEN, Shu-zhen (Beijing) DING, Fei (Nantong) BARTON, Samantha (Parkville) CHEN, Tian-feng (Guangzhou) DING, Jin-song (Changsha) BAY, Boon Huat (Singapore) CHEN, Wan-jin (Fuzhou) DING, Jun-jie (Shanghai) -

The Thirty-Six Strategies of Ancient China Stefan H

The Thirty-Six Strategies of Ancient China Stefan H. Verstappen Copyright 1999 by Stefan H. Verstappen First Edition Published by China Books, SF 1999 E Book Edition 2012 ISBN 978-0-9869515-8-9 Smashwords Edition Table of Contents Introduction 1: Fool the Emperor to Cross the Sea 2: Besiege Wei to Rescue Zhao 3: Kill with a Borrowed Sword 4: Await the Exhausted Enemy at Your Ease 5: Loot a Burning House 6: Clamour in the East, Attack in the West 7: Create Something from Nothing 8: Openly Repair the Walkway, Secretly March to Chencang 9: Observe the Fire on the Opposite Shore 10: Hide Your Dagger Behind a Smile 11: Sacrifice the Plum Tree In Place of the Peach 12: Seize the Opportunity to Lead a Sheep Away 13: Beat the Grass to Startle the Snake 14: Borrow a Corpse to Raise the Spirit 15: Lure the Tiger Down the Mountain 16: To Catch Something, First Let It Go 17: Toss Out a Brick to Attract Jade 18: To Catch the Bandits First Capture Their Leader 19: Steal the Firewood From Under the Pot 20: Trouble the water to catch the fish 21: Shed Your Skin Like the Golden Cicada 22: Shut the Door to Catch the Thief 23: Befriend a Distant Enemy to Attack One Nearby 24: Borrow the Road to Conquer Guo 25: Replace the Beams with Rotten Timbers 26: Point at the Mulberry but Curse the Locust Tree 27: Feign Madness but Keep Your Balance 28: Lure Your Enemy Onto the Roof, Then Take Away the Ladder 29: Tie Silk Blossoms to the Dead Tree 30: Exchange the Role of Guest for that of Host 31: The Strategy of Beautiful Women 32: The Strategy of Open City Gates 33: The Strategy of Sowing Discord 34: The Strategy of Injuring Yourself 35: The Strategy of Combining Tactics 36: If All Else Fails Retreat Chronological Table Bibliography INTRODUCTION The THIRTY-SIX STRATEGIES is a unique collection of ancient Chinese proverbs that describe some of the most cunning and subtle war tactics ever devised. -

POLICIES for CATALOGING CHINESE MATERIAL: SUPPLEMENT to the CHINESE ROMANIZATION GUIDELINES Revised September 22, 2004

ROMANIZATION POLICIES FOR CATALOGING CHINESE MATERIAL: SUPPLEMENT TO THE CHINESE ROMANIZATION GUIDELINES Revised September 22, 2004 This supplement builds on the Chinese romanization guidelines that appear on the Library of Congress pinyin home page (http://lcweb.loc.gov/catdir/cpso/romanization/chinese.pdf). The revision of the Chinese guidelines corresponded with the conversion of Wade-Giles romanization in authority and bibliographic records to pinyin on October 1, 2000. The revised romanization guidelines will replace the Wade-Giles guidelines in the ALA-LC romanization tables when it is next updated. The supplement is intended to help catalogers make certain important distinctions when romanizing Chinese personal and place names. RULES OF APPLICATION Romanization 1. ALA-LC romanization of ideographic characters used for the Chinese language follows the principles of the Pinyin ("spell sound") system. The Pinyin system was developed in the mid 20th century for creating Latin script readings for Chinese script ideographic characters. It replaces the Wade-Giles system of romanization specified in earlier editions of the ALA-LC Romanization Tables. The Pinyin system as outlined in Han yu pin yin fang an 汉语拼音方案 (1962) is followed closely for creating romanizations except that the ALA-LC guidelines do not include the indication of tone marks. 2. Standard Chinese national (PRC) pronunciation is used as the basis for creating the Latin script reading of a character. When it is necessary to make semantic distinctions between multiple readings of a single character, rely upon the usage of the most recent comprehensive edition of Ci hai 辞海 (published in China by Shanghai ci shu chu ban she). -

Bibliography of Chinese Linguistics William S.-Y.Wang

BIBLIOGRAPHY OF CHINESE LINGUISTICS WILLIAM S.-Y.WANG INTRODUCTION THIS IS THE FIRST LARGE-SCALE BIBLIOGRAPHY OF CHINESE LINGUISTICS. IT IS INTENDED TO BE OF USE TO STUDENTS OF THE LANGUAGE WHO WISH EITHER TO CHECK THE REFERENCE OF A PARTICULAR ARTICLE OR TO GAIN A PERSPECTIVE INTO SOME SPECIAL TOPIC OF RESEARCH. THE FIELD OF CHINESE LINGUIS- TICS HAS BEEN UNDERGOING RAPID DEVELOPMENT IN RECENT YEARS. IT IS HOPED THAT THE PRESENT WORK WILL NURTURE THIS DEVELOP- MENT BY PROVIDING A SENSE OF THE SIZABLE SCHOLARSHIP IN THE FIELD» BOTH PAST AND PRESENT. IN SPITE OF REPEATED CHECKS AND COUNTERCHECKS, THE FOLLOWING PAGES ARE SURE TO CONTAIN NUMEROUS ERRORS OF FACT, SELECTION AND OMISSION. ALSO» DUE TO UNEVENNESS IN THE LONG PROCESS OF SELECTION, THE COVERAGE HERE IS NOT UNIFORM. THE REPRESENTATION OF CERTAIN TOPICS OR AUTHORS IS PERHAPS NOT PROPORTIONAL TO THE EXTENT OR IMPORTANCE BIBLIOGRAPHY OF CHINESE LINGUISTICS ]g9 OF THE CORRESPONDING LITERATURE. THE COVERAGE CAN BE DIS- CERNED TO BE UNBALANCED IN TWO MAJOR WAYS. FIRST. THE EMPHASIS IS MORE ON-MODERN. SYNCHRONIC STUDIES. RATHER THAN ON THE WRITINGS OF EARLIER CENTURIES. THUS MANY IMPORTANT MONOGRAPHS OF THE QING PHILOLOGISTS. FOR EXAMPLE, HAVE NOT BEEN INCLUDED HERE. THOUGH THESE ARE CERTAINLY TRACE- ABLE FROM THE MODERN ENTRIES. SECOND, THE EMPHASIS IS HEAVILY ON THE SPOKEN LANGUAGE, ALTHOUGH THERE EXISTS AN ABUNDANT LITERATURE ON THE CHINESE WRITING SYSTEM. IN VIEW OF THESE SHORTCOMINGS, I HAD RESERVATIONS ABOUT PUBLISHING THE BIBLIOGRAPHY IN ITS PRESENT STATE. HOWEVER, IN THE LIGHT OF OUR EXPERIENCE SO FAR, IT IS CLEAR THAT A CONSIDERABLE AMOUNT OF TIME AND EFFORT IS STILL NEEDED TO PRODUCE A COMPREHENSIVE BIBLIOGRAPHY THAT IS AT ONCE PROPERLY BALANCED AMD COMPLETELY ACCURATE (AND, PERHAPS, WITH ANNOTATIONS ON THE IMPORTANT ENTRIES). -

4.3 the Rise of the Han

Indiana University, History G380 – class text readings – Spring 2010 – R. Eno 4.3 THE RISE OF THE HAN The emergence of the Han Dynasty represents the full confluence of two seemingly contradictory trends that had been increasingly paired since the time of Shang Yang: meritocracy and autocracy. The First Emperor, through his conscious exaltation of his throne and his thorough rejection of Zhou feudalism and hereditary privilege, had created the conditions for the institutionalization of these forces. The founder of the Han Dynasty, Liu Pang, was from a peasant family; during the Qin he served as a petty official in a peripheral region of China. He succeeded to the imperial throne only by prevailing in a civil war that lasted for over four years after the surrender of Ziying, the last ruler of the Qin. His principal opponent during that period was a man named Xiang Yu, who represented everything that Liu Bang was not. Xiang Yu was of patrician stock, a scion of the house of Chu, and the model of a Zhou-style warrior: brave, skillful, elegant, and bloodthirsty. Xiang Yu began as the leader of the very forces that brought Liu Bang to power, and was, for a time, acknowledged by all, including Liu, to be the founder of the successor dynasty to the Qin. Yet he was destroyed by the supporters of a subordinate from the peasant class. Liu Bang ascended the throne in 202 B.C.,* less than twenty years after the end of the Warring States period. How confounding it must have been to the elder generation to see a peasant occupying the seat of power! An overview of the civil wars (209-202) Chen She's uprising, 209-208. -

“Mountain-Dwelling Poems”: a Translation

Tang Studies, 34. 1, 99–124, 2016 GUANXIU’S “MOUNTAIN-DWELLING POEMS”: A TRANSLATION THOMAS J. MAZANEC Princeton University, USA This is a translation of one of the most influential poetic series of the late-ninth century, the twenty-four “Mountain-Dwelling Poems” written by the Buddhist monk Guanxiu (832–913). Focusing on the speaker’s use of imagery and allusion, the translations are accompanied by annotations which clarify obscure or difficult passages. An introduction places these poems in their historical context and high- lights some of the ways in which they build syntheses out of perceived oppositions (original and revision; Buddhism, Daoism, and classical reclusion; solitude and community; reader’s various perspectives; poem and series). An afterword briefly sketches the method and circumstances of the translation. KEYWORDS: poetry, Late Tang, reclusion, Buddhism, translation INTRODUCTION Poet of witness and sycophantic hack, vernacularizer and archaizer, dealmaker and recluse, Buddhist meditator and alchemical experimenter, eternal itinerant and homesick Wu native, pious monk and bristly bastard, Guanxiu 貫休 (832–913) con- tained multitudes. He was the most sought after Buddhist writer of his day, patron- ized by three major rulers.1 His work was praised by his peers as the successor of both the political satires of Bai Juyi 白居易 (772–846) and the boundlessly imagina- tive landscapes of Li Bai 李白 (701–62) and Li He 李賀 (790–816).2 His paintings of I would like to thank Jason Protass for sharing some of his notes on later readings of these poems with me. My colleagues Yixin Gu and Yuanxin Chen, as well as the anonymous readers of this manuscript, offered valuable comments and suggestions, some of which I have ignored at my own peril. -

Annual Report HKEX 01025 2012 HKEX 01025 2012 Annual Report 2012 年報 Corporate Vision

年 報 Annual Report HKEX 01025 2012 HKEX 01025 2012 Annual Report Annual 2012 年報 Corporate Vision A dream we share — a dream of establishing an everlasting retail chain that Chinese people love patronizing, and that mingles with their daily lives — Wumart, thereby to provide the public with satisfying products and service and dedicate our wisdom and power to the pursuit of developing modern circulation industry and improving the life quality of the public. Contents 2 Company Information 4 Chairman’s Statement 10 Management Discussion and Analysis 24 Profile of Directors, Supervisors and Senior Management 28 Report of the Board of Directors 37 Report of the Supervisory Committee 39 Corporate Governance Report 49 Independent Auditor’s Report 51 Consolidated Statement of Comprehensive Income 52 Consolidated Statement of Financial Position 54 Consolidated Statement of Changes in Equity 55 Consolidated Statement of Cash Flows 57 Notes to the Consolidated Financial Statements 107 Financial Summary Wumart Stores, Inc. 2 Company Information BOARD OF DIRECTORS Independent Non-executive SENIOR MANAGEMENT Directors Mr. Xu Shao-chuan Executive Directors Mr. Han Ying (Vice President, General Manager Dr. Wu Jian-zhong (Chairman) Mr. Li Lu-an of Wumart Beijing Supermarket Madam Xu Ying (President) Mr. Lu Jiang Business Unit) Dr. Meng Jin-xian (Vice President) Note Mr. Wang Jun-yan Mr. Chong Xiao-bing Dr. Yu Jian-bo (Vice President) (Assistant President and Vice SUPERVISORY General Manager of Wumart Non-executive Directors Beijing Supermarket Business COMMITTEE Mr. Wang Jian-ping Unit) (Vice Chairman) Note Mr. Fan Kui-jie (Chairman) Mr. Zhang Yu Mr. John Huan Zhao Madam Xu Ning-chun (Executive Director of Finance Madam Ma Xue-zheng Mr.