ETD Template

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lorado Taft Midway Studios AND/OR COMMON Lorado Taft Midway Studios______I LOCATION

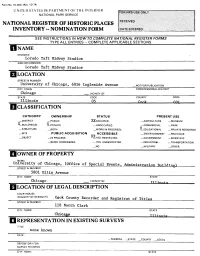

Form No. 10-300 (Rev. 10-74) UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR NATIONAL PARK SERVICE NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES INVENTORY -- NOMINATION FORM SEE INSTRUCTIONS IN HOW TO COMPLETE NATIONAL REGISTER FORMS ___________TYPE ALL ENTRIES - COMPLETE APPLICABLE SECTIONS______ | NAME HISTORIC Lorado Taft Midway Studios AND/OR COMMON Lorado Taft Midway Studios______________________________ I LOCATION STREET & NUMBER University of Chicago, 6016 Ingleside Avenue —NOT FOR PUBLICATION CITY. TOWN CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT Chicago __ VICINITY OF STATE CODE COUNTY CODE Illinois 05 P.onV CLASSIFICATION CATEGORY OWNERSHIP STATUS PRESENT USE _DISTRICT —PUBLIC XXOCCUPIED _ AGRICULTURE —MUSEUM X_BUILDING(S) ?_PRIVATE —UNOCCUPIED —COMMERCIAL —PARK —STRUCTURE —BOTH _ WORK IN PROGRESS ^-EDUCATIONAL —PRIVATE RESIDENCE _ SITE PUBLIC ACQUISITION ACCESSIBLE —ENTERTAINMENT —RELIGIOUS —OBJECT —IN PROCESS —YES: RESTRICTED —GOVERNMENT —SCIENTIFIC —BEING CONSIDERED _ YES: UNRESTRICTED —INDUSTRIAL —TRANSPORTATION _NO —MILITARY —OTHER. (OWNER OF PROPERTY NAMEINAMt University of Chicago, (Office of Special Events, Administration STREET & NUMBER 5801 Ellis Avenue CITY. TOWN STATE VICINITY OF Chicago T1 1 inr>i' a LOCATION OF LEGAL DESCRIPTION COURTHOUSE, REGISTRY OF DEEps.ETc. Cook County Recorder and Registrat of Titles STREET & NUMBER 118 North Clark CITY. TOWN STATE Chicago Tllinm', REPRESENTATION IN EXISTING SURVEYS TITLE none known DATE — FEDERAL —STATE —COUNTY —LOCAL DEPOSITORY FOR SURVEY RECORDS CITY. TOWN STATE DESCRIPTION CONDITION CHECK ONE CHECK ONE YY —EXCELLENT _DETERIORATED —UNALTERED —ORIGINAL SITE XXQOOD —RUINS XXALTERED —MOVED DATE_______ —FAIR —UNEXPOSED DESCRIBETHE PRESENT AND ORIGINAL (IF KNOWN) PHYSICAL APPEARANCE Lorado Taft's wife, Ada Bartlett Taft y described the Midway Studios in her biography of her husband, Lorado Taft, Sculptor arid Citizen; In 1906 Lorado moved his main studio out of the crowded Loop into a large, deserted brick barn on the University of Chicago property on the Midway. -

1835. EXECUTIVE. *L POST OFFICE DEPARTMENT

1835. EXECUTIVE. *l POST OFFICE DEPARTMENT. Persons employed in the General Post Office, with the annual compensation of each. Where Compen Names. Offices. Born. sation. Dol. cts. Amos Kendall..., Postmaster General.... Mass. 6000 00 Charles K. Gardner Ass't P. M. Gen. 1st Div. N. Jersey250 0 00 SelahR. Hobbie.. Ass't P. M. Gen. 2d Div. N. York. 2500 00 P. S. Loughborough Chief Clerk Kentucky 1700 00 Robert Johnson. ., Accountant, 3d Division Penn 1400 00 CLERKS. Thomas B. Dyer... Principal Book Keeper Maryland 1400 00 Joseph W. Hand... Solicitor Conn 1400 00 John Suter Principal Pay Clerk. Maryland 1400 00 John McLeod Register's Office Scotland. 1200 00 William G. Eliot.. .Chie f Examiner Mass 1200 00 Michael T. Simpson Sup't Dead Letter OfficePen n 1200 00 David Saunders Chief Register Virginia.. 1200 00 Arthur Nelson Principal Clerk, N. Div.Marylan d 1200 00 Richard Dement Second Book Keeper.. do.. 1200 00 Josiah F.Caldwell.. Register's Office N. Jersey 1200 00 George L. Douglass Principal Clerk, S. Div.Kentucky -1200 00 Nicholas Tastet Bank Accountant Spain. 1200 00 Thomas Arbuckle.. Register's Office Ireland 1100 00 Samuel Fitzhugh.., do Maryland 1000 00 Wm. C,Lipscomb. do : for) Virginia. 1000 00 Thos. B. Addison. f Record Clerk con-> Maryland 1000 00 < routes and v....) Matthias Ross f. tracts, N. Div, N. Jersey1000 00 David Koones Dead Letter Office Maryland 1000 00 Presley Simpson... Examiner's Office Virginia- 1000 00 Grafton D. Hanson. Solicitor's Office.. Maryland 1000 00 Walter D. Addison. Recorder, Div. of Acc'ts do.. -

Violent Conflict and Regional Institutionalization: a Virtuous Circle?

VIOLENT CONFLICT AND REGIONAL INSTITUTIONALIZATION: A VIRTUOUS CIRCLE? DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Ze’ev Yoram Haftel, M.A. * * * * * The Ohio State University 2004 Dissertation Committee: Approved By Professor Brian M. Pollins, Advisor Professor Donald A. Sylvan _______________________________ Professor Alexander Thompson Advisor Graduate Program in Political Science ABSTRACT International institutions have attracted a great deal of attention from scholars of international relations. A cursory look at the universe of international institutions reveals immense diversity. Yet systematic analysis of institutional variation is lacking, and the sources and effects of this variation are not well understood. My dissertation examines variation in one important type of international institution, regional integration arrangements (RIAs), and its relationship with violent conflict. The theoretical chapter explores possible causal paths by which regional institutionalization affects intramural violent conflict. It points to specific institutional features that correspond to alternative causal mechanisms advanced in the extant literature. It then considers possible effects of intramural conflict on regional institutionalization. The next chapter elaborates on the concept of regional institutionalization, and presents an original dataset by coding twenty-five RIAs on this variable. This data set points to a considerable -

National Park Service Mission 66 Era Resources B

NPS Form 10-900-b (Rev. 01/2009) 0MB No. 1024-0018 (Expires 5/31/2012) UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Multiple Property Documentation Form This form Is used for documenting property groups relating to one or several historic contexts. See instructil'.r!§ ~ ~ tloDpl lj~~r Bulletin How to Complete the Mulliple Property Doc11mentatlon Form (formerly 16B). Complete each item by entering the req lBtEa\oJcttti~ll/~ a@i~8CPace, use continuation sheets (Form 10-900-a). Use a typewriter, word processor, or computer to complete all items X New Submission Amended Submission AUG 1 4 2015 ---- ----- Nat Register of Historie Places A. Name of Multiple Property Listing NatioAal Park Service National Park Service Mission 66 Era Resources B. Associated Historic Contexts (Name each associated historic context, identifying theme, geographical area, and chronological period for each.) Pre-Mission 66 era, 1945-1955; Mission 66 program, 1956-1966; Parkscape USA program, 1967-1972, National Park Service, nation-wide C. Form Prepared by name/title Ethan Carr (Historical Landscape Architect); Elaine Jackson-Retondo, Ph.D., (Historian, Architectural); Len Warner (Historian). The Collaborative Inc.'s 2012-2013 team comprised Rodd L. Wheaton (Architectural Historian and Supportive Research), Editor and Contributing Author; John D. Feinberg, Editor and Contributing Author; and Carly M. Piccarello, Editor. organization the Collaborative, inc. date March 2015 street & number ---------------------2080 Pearl Street telephone 303-442-3601 city or town _B_o_ul_d_er___________ __________st_a_te __ C_O _____ zi~p_c_o_d_e_8_0_30_2 __ _ e-mail [email protected] organization National Park Service Intermountain Regional Office date August 2015 street & number 1100 Old Santa Fe Trail telephone 505-988-6847 city or town Santa Fe state NM zip code 87505 e-mail sam [email protected] D. -

Wagon Tracks. Volume 17, Issue 4 (August, 2003) Santa Fe Trail Association

Wagon Tracks Volume 17 Issue 4 Wagon Tracks Volume 17, Issue 4 (August Article 1 2003) 2003 Wagon Tracks. Volume 17, Issue 4 (August, 2003) Santa Fe Trail Association Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/wagon_tracks Part of the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Santa Fe Trail Association. "Wagon Tracks. Volume 17, Issue 4 (August, 2003)." Wagon Tracks 17, 4 (2003). https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/wagon_tracks/vol17/iss4/1 This Full Issue is brought to you for free and open access by UNM Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Wagon Tracks by an authorized editor of UNM Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. : Wagon Tracks. Volume 17, Issue 4 (August, 2003) SANTA FE TRAIL ASSOCIATION QUARTERLY VOLUME 17 AUGUST 2003 NUMBER4 INDEPENDENCE: QUEEN CITY OF THE TRAILS SEPTEMBER 7, 2003 DAR MADONNA REDEDICA· by Jane Mallinson TlON AT COUNCIL GROVE, KS [SFTA Ambassador Jane Mallinson SEPTEMBER 24,2003 is a charter member of SFTA and a frequent contributor to WT.] SFTA BOARD MEETING For symposium reservations, KANSAS CITY , please note correct phone INDEPENDENCE, MO, will be one SEPTEMBER 24-28, 2003 number for Days Inn South the host cities for the 2003 sympo of East Motel in Kansas City: sium. While visiting Independence, SFTA SYMPOSIUM noted author David McCullough KANSAS CITY AREA (816) 765-4331 said, "I can't think of another piece of landscape of similar size where so SIX WESTERN CHAPTERS GATHERING AT SANTA FE, JUNE 14-15 many things have happened that by Inez Ross . -

Women and the American Wilderness: Responses to Landscape and Myth Gina Bessetti-Reyes

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Duquesne University: Digital Commons Duquesne University Duquesne Scholarship Collection Electronic Theses and Dissertations Spring 2014 Women and the American Wilderness: Responses to Landscape and Myth Gina Bessetti-Reyes Follow this and additional works at: https://dsc.duq.edu/etd Recommended Citation Bessetti-Reyes, G. (2014). Women and the American Wilderness: Responses to Landscape and Myth (Doctoral dissertation, Duquesne University). Retrieved from https://dsc.duq.edu/etd/308 This Immediate Access is brought to you for free and open access by Duquesne Scholarship Collection. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Duquesne Scholarship Collection. For more information, please contact [email protected]. WOMEN AND THE AMERICAN WILDERNESS: RESPONSES TO LANDSCAPE AND MYTH A Dissertation Submitted to the McAnulty College and Graduate School of Liberal Arts Duquesne University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy By Gina Marie Bessetti-Reyes May 2014 Copyright by Gina Marie Bessetti-Reyes 2014 WOMEN AND THE AMERICAN WILDERNESS: RESPONSES TO LANDSCAPE AND MYTH By Gina Marie Bessetti-Reyes Approved March 10, 2014 ________________________________ ________________________________ Thomas Kinnahan, Ph.D. Linda Kinnahan, Ph.D. Assistant Professor of English Professor of English (Committee Chair) (Committee Member) ________________________________ Kathy Glass, Ph.D. Associate Professor of English (Committee Member) ________________________________ ________________________________ James Swindal, Ph.D. Dr. Greg Barnhisel, Ph.D. Dean, McAnulty College and Graduate Chair, English Department School of Liberal Arts Associate Professor of English Professor of Philosophy iii ABSTRACT WOMEN AND THE AMERICAN WILDERNESS: RESPONSES TO LANDSCAPE AND MYTH By Gina Marie Bessetti-Reyes May 2014 Dissertation supervised by Thomas Kinnahan, Ph.D. -

America's Catholic Church"

rfHE NATION'S CAPITAL CELEBRArfES 505 YEARS OF DISCOVERY HONORING THE GREA1" DISCOVERER CHRISTOPHER COLUMBUS MONDAY OCTOBER 12. 1998 THE COLUMBUS MEMORIAL COLUMBUS PI~AZA - UNION STATION. W ASIIlNGTON. D.C. SPONSORED BY THE WASHINGTON COLUMBUS CELEBRATION ASSOCIATION IN COORDINATION WITH THE NATIONAL PARK SERVICE CELEBRATING CHRISTOPHER COLUMBUS IN THE NATION'S CAPITAL The Site In the years following the great quadricentennial (400th anniversary) celebration in 1892 of the achievements and discoveries of Christopher Cohnnbus, an effort was launched by the Knights of ~ Columbus to establish a monument to the ~ great discoverer. The U. S. Congress passed a law which mandated a Colwnbus Memorial in the nation's capital and appropriated $100,000 to cover the ~· ~, ·~-~=:;-;~~ construction costs. A commission was T" established composed of the secretaries of State and War, the chairmen of the House and Senate Committees on the Library of Congress, and the Supreme Knight of the Knights of Columbus. With the newly completed Union Railroad Station in 1907, plans focused toward locating the memorial on the plaz.a in front of this great edifice. After a series of competitions, sculptor Lorado Z. Taft of Chicago was awarded the contract. His plan envisioned what you see this day, a monument constructed of Georgia marble; a semi-circular fountain sixty-six feet broad and forty-four feet deep and in the center, a pylon crowned with a globe supported by four eagles oonnected by garland. A fifteen foot statue of Columbus, facing the U. S. Capitol and wrapped in!\ medieval mantle, stands in front of the pylon in the bow of a ship with its pn,, extending into the upper basin of the fountain terminating with a winged figurehead representing democracy. -

Pullman Company Archives

PULLMAN COMPANY ARCHIVES THE NEWBERRY LIBRARY Guide to the Pullman Company Archives by Martha T. Briggs and Cynthia H. Peters Funded in Part by a Grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities Chicago The Newberry Library 1995 ISBN 0-911028-55-2 TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction ............................................. v - xii ... Access Statement ............................................ xiii Record Group Structure ..................................... xiv-xx Record Group No . 01 President .............................................. 1 - 42 Subgroup No . 01 Office of the President ...................... 2 - 34 Subgroup No . 02 Office of the Vice President .................. 35 - 39 Subgroup No . 03 Personal Papers ......................... 40 - 42 Record Group No . 02 Secretary and Treasurer ........................................ 43 - 153 Subgroup No . 01 Office of the Secretary and Treasurer ............ 44 - 151 Subgroup No . 02 Personal Papers ........................... 152 - 153 Record Group No . 03 Office of Finance and Accounts .................................. 155 - 197 Subgroup No . 01 Vice President and Comptroller . 156 - 158 Subgroup No. 02 General Auditor ............................ 159 - 191 Subgroup No . 03 Auditor of Disbursements ........................ 192 Subgroup No . 04 Auditor of Receipts ......................... 193 - 197 Record Group No . 04 Law Department ........................................ 199 - 237 Subgroup No . 01 General Counsel .......................... 200 - 225 Subgroup No . 02 -

Historic Resources of the Santa Fe Trail (Revised)

NPS Form 10-900-b (Rev. 01/2009) OMB No. 1024-0018 (Expires 5/31/2012) United States Department of the Interior National Park Service NPS Approved – April 3, 2013 National Register of Historic Places Multiple Property Documentation Form This form is used for documenting property groups relating to one or several historic contexts. See instructions in National Register Bulletin How to Complete the Multiple Property Documentation Form (formerly 16B). Complete each item by entering the requested information. For additional space, use continuation sheets (Form 10-900-a). Use a typewriter, word processor, or computer to complete all items New Submission X Amended Submission A. Name of Multiple Property Listing Historic Resources of the Santa Fe Trail (Revised) B. Associated Historic Contexts (Name each associated historic context, identifying theme, geographical area, and chronological period for each.) I. The Santa Fe Trail II. Individual States and the Santa Fe Trail A. International Trade on the Mexican Road, 1821-1846 A. The Santa Fe Trail in Missouri B. The Mexican-American War and the Santa Fe Trail, 1846-1848 B. The Santa Fe Trail in Kansas C. Expanding National Trade on the Santa Fe Trail, 1848-1861 C. The Santa Fe Trail in Oklahoma D. The Effects of the Civil War on the Santa Fe Trail, 1861-1865 D. The Santa Fe Trail in Colorado E. The Santa Fe Trail and the Railroad, 1865-1880 E. The Santa Fe Trail in New Mexico F. Commemoration and Reuse of the Santa Fe Trail, 1880-1987 C. Form Prepared by name/title KSHS Staff, amended submission; URBANA Group, original submission organization Kansas State Historical Society date Spring 2012 street & number 6425 SW 6th Ave. -

Ursula Mctaggart

RADICALISM IN AMERICA’S “INDUSTRIAL JUNGLE”: METAPHORS OF THE PRIMITIVE AND THE INDUSTRIAL IN ACTIVIST TEXTS Ursula McTaggart Submitted to the faculty of the University Graduate School in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy In the Departments of English and American Studies Indiana University June 2008 Accepted by the Graduate Faculty, Indiana University, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Doctoral Committee ________________________________ Purnima Bose, Co-Chairperson ________________________________ Margo Crawford, Co-Chairperson ________________________________ DeWitt Kilgore ________________________________ Robert Terrill June 18, 2008 ii © 2008 Ursula McTaggart ALL RIGHTS RESERVED iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS A host of people have helped make this dissertation possible. My primary thanks go to Purnima Bose and Margo Crawford, who directed the project, offering constant support and invaluable advice. They have been mentors as well as friends throughout this process. Margo’s enthusiasm and brilliant ideas have buoyed my excitement and confidence about the project, while Purnima’s detailed, pragmatic advice has kept it historically grounded, well documented, and on time! Readers De Witt Kilgore and Robert Terrill also provided insight and commentary that have helped shape the final product. In addition, Purnima Bose’s dissertation group of fellow graduate students Anne Delgado, Chia-Li Kao, Laila Amine, and Karen Dillon has stimulated and refined my thinking along the way. Anne, Chia-Li, Laila, and Karen have devoted their own valuable time to reading drafts and making comments even in the midst of their own dissertation work. This dissertation has also been dependent on the activist work of the Black Panther Party, the League of Revolutionary Black Workers, the International Socialists, the Socialist Workers Party, and the diverse field of contemporary anarchists. -

Madonna of the Trail Lexington, Missouri the Statue Is a Tribute to the Many Hundreds of Thousands of Women Who Took Part In

Madonna of the Trail Lexington, Missouri The statue is a tribute to the many hundreds of thousands of women who took part in the Western United States Migration. Madonna of the Trail is a series of 12 identical monuments dedicated to the sprit of pioneer women in the United States. In the late 1920’s, the National Society of the Daughters of the American Revolution (NSDAR) commissioned the design, casting and placement of twelve memorials commemorating the spirit of pioneer women. These monuments were installed in each of 12 states along the National Old Trails Road, which extended from Cumberland, Maryland, to Upland, California. The Madonna of the Trail is depicted as a courageous pioneer woman, clasping her baby with her left arm while clutching her rifle in her right, wearing a long dress and bonnet. Her young son clings to her skirts. On Monday, September 17, 1928, The Missouri Madonna of the Trail in Lexington, Missouri, was unveiled and dedicated. Harry S. Truman, a Missouri Justice of the Peace and the President of the National Old Trails Association, was the keynote speaker at the ceremony. The ceremony was in many ways a “home-coming” for Lexington, and the streets were crowded with visitors while homes were filled with guests. Most of the visitors were former residents, relatives, and people with connections with Lexington. Many people dressed in period costume, including some eighty-plus year old “real pioneer women” who were dressed in costumes that were over 100 years old. On August 25, 1928, prior to the dedication, a copper box time capsule, filled with pictures, books, pamphlets and other miscellaneous items, was deposited in the base of the pioneer mother statue. -

FINAL.Fountain of the Pioneers NR

NPS Form 10-900 OMB No. 1024-0018 United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form This form is for use in nominating or requesting determinations for individual properties and districts. See instructions in National Register Bulletin, How to Complete the National Register of Historic Places Registration Form. If any item does not apply to the property being documented, enter "N/A" for "not applicable." For functions, architectural classification, materials, and areas of significance, enter only categories and subcategories from the instructions. 1. Name of Property Historic name: _Fountain of the Pioneers _______________________________ Other names/site number: Fountain of the Pioneers complex, Iannelli Fountain Name of related multiple property listing: Kalamazoo MRA; reference number 64000327___________________________________ (Enter "N/A" if property is not part of a multiple property listing ___________________________________________________________________________ 2. Location Street & number: _in Bronson Park, bounded by Academy, Rose, South and Park Streets_ City or town: _Kalamazoo___ State: _Michigan_ County: _Kalamazoo__ Not For Publication: Vicinity: ____________________________________________________________________________ 3. State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act, as amended, I hereby certify that this X nomination ___ request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation