Westin 11/02

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

It Comes from Placement of a News Story in a Broadsheet Newspaper Above the Fold in the Middle of the Front Page

Above the fold: A term used to refer to a prominent story; it comes from placement of a news story in a broadsheet newspaper above the fold in the middle of the front page. Actual malice: A reckless disregard for the truth or falsity of a published account; this became the standard for libel plaintiffs who were public figures or public officials after the Supreme Court's decision in New York Times v. Sullivan Advertising: Defined by the American Marketing Association as “any paid form of non-personal communication about an organization, product, service, or idea by an identified sponsor." Advertorials: advertising materials in magazines designed to look like editorial content rather than paid advertising. Advocacy ads: Advertising designed to promote a particular point of view rather than a product or service. Can be sponsored by government, corporation, trade association, product or nonprofit organization. Aggregator site: An organizing Web site that provides surfers with easy access to e-mail, news, online stores, and many other sites. Alien and Sedition Acts: Laws passed in 1798 that made it a crime to criticize the government of the United States. Al Jazeera: The largest and most viewed Arabic-language satellite news channel. It is run out of the country of Qatar and has a regular audience of 40 million viewers. Alternative papers: Weekly newspapers that serve specialized audiences ranging from racial minorities, to gays and lesbians, to young people. ARPAnet: The Advanced Research Projects Agency Network; the first nationwide computer network, which would become the first major component of the Internet. Authoritarian theory: A theory of appropriate press behavior that says the role of the press is to be a servant of the government, not a servant of the citizenry. -

Murder-Suicide Ruled in Shooting a Homicide-Suicide Label Has Been Pinned on the Deaths Monday Morning of an Estranged St

-* •* J 112th Year, No: 17 ST. JOHNS, MICHIGAN - THURSDAY, AUGUST 17, 1967 2 SECTIONS - 32 PAGES 15 Cents Murder-suicide ruled in shooting A homicide-suicide label has been pinned on the deaths Monday morning of an estranged St. Johns couple whose divorce Victims had become, final less than an hour before the fatal shooting. The victims of the marital tragedy were: *Mrs Alice Shivley, 25, who was shot through the heart with a 45-caliber pistol bullet. •Russell L. Shivley, 32, who shot himself with the same gun minutes after shooting his wife. He died at Clinton Memorial Hospital about 1 1/2 hqurs after the shooting incident. The scene of the tragedy was Mrsy Shivley's home at 211 E. en name, Alice Hackett. Lincoln Street, at the corner Police reconstructed the of Oakland Street and across events this way. Lincoln from the Federal-Mo gul plant. It happened about AFTER LEAVING court in the 11:05 a.m. Monday. divorce hearing Monday morn ing, Mrs Shivley —now Alice POLICE OFFICER Lyle Hackett again—was driven home French said Mr Shivley appar by her mother, Mrs Ruth Pat ently shot himself just as he terson of 1013 1/2 S. Church (French) arrived at the home Street, Police said Mrs Shlv1 in answer to a call about a ley wanted to pick up some shooting phoned in fromtheFed- papers at her Lincoln Street eral-Mogul plant. He found Mr home. Shivley seriously wounded and She got out of the car and lying on the floor of a garage went in the front door* Mrs MRS ALICE SHIVLEY adjacent to -• the i house on the Patterson got out of-'the car east side. -

Mother's Forgotten Garden

MOTHER'S FORGOTTEN GARDEN by Cory Daniel Zimmerman A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of The Dorothy F. Schmidt College of Arts and Letters in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Fine Arts Florida Atlantic University Boca Raton, Florida December 2008 Copyright by Cory Daniel Zimmerman 2008 ii Abstract Author: Cory Daniel Zimmerman Title: Mother’s Forgotten Garden Institution: Florida Atlantic University Thesis Advisor: Dr. Jason Schwartz Degree: Master of Fine Arts Year: 2008 The thesis proposed for my M.F.A. in creative writing is a collection of conceptual American short stories written in a variety of forms that properly suit their respective subjects. Like a handful of miscellaneous wild seeds scattered over a tilled garden, the goal of the project is to represent the wild asymmetry of Nature via a collection of unlikely companions. For this reason, the conceptual form of each story often takes root in scientific or symbolic representations of Nature (i.e. sine and cosine curves, the yin-yang, etc.). The plot of loose soil holding these collective experiments together is their earthy thematic focus—namely, the way in which Nature has been systematically backgrounded by western ideology. On occasion, a story’s conceptual focus may stray from these ecofeminist principles, but only for the purpose of leveling a more critical or satirical eye upon common American ideologies. iv Table of Contents The cosmis joke redux ...................................................................................................... -

Women in Nigerian News Media: Status, Experiences and Structures

Women in Nigerian News Media: Status, Experiences and Structures. Ganiyat Tijani-Adenle Abstract This study investigates women journalists’ experience of journalism practice in Nigeria and reviews the structures that moderate those experiences. The thesis employs an ethnographic approach in answering the research questions. An observation of women journalists’ interaction with their colleagues in the newsrooms of two news media organisations were conducted for a total of four weeks, 46 media workers (two HR managers, one production staff, 11 male journalists and 32 female journalists) were interviewed and the staff regulation and policy handbooks of five news organisations were reviewed to understand Nigerian news media organisations’ equality and gender policies. A study grounded in African feminist theory and a phenomenological approach to research; this thesis privileges women journalists’ experiences and is focused primarily on documenting how they experience the news industry in Nigeria. Analysing findings using thematic analysis, the study reveals that women journalists experience various inequalities in the Nigerian news industry. Key findings are that even though more women are increasingly covering the hard beats, women journalists are nonetheless clustered in the soft beats. Contrary to previous evidence, pay equality is in theory but not practice as negotiation, nepotism and gender norms sometimes cause salary differentials for men and women journalists. The non-payment of salaries drives women out of media organisations. Sexual harassment and sexism are rife in Nigerian news companies and many organisations do not have policies and frameworks to address them, the few who handle sexual harassment complaints do so unofficially and off the records. Marriage and motherhood are the dominant factors creating glass ceilings for women journalists working in the Nigerian news media. -

David C. Hazinski

David C. Hazinski EMPLOYMENT HISTORY UNIVERSITY OF GEORGIA (ATHENS, GA.) Associate Professor/Head, Digital & Broadcast Journalism , Josiah Meigs Distinguished Teaching Professor, Kennedy Professor of New Media. Henry W. Grady College of Journalism and Mass Communication. 1987 to present. Teach upper level and graduate professional courses in radio/ television news production, broadcast news writing, documentary production and advanced television news. Leads a professional focused faculty which originated and administers student-produced, commercially broadcast college news and public affairs television programs. NBC NEWS (NEW YORK, N.Y.) Correspondent, 1981-1987. International network news correspondent based in the Atlanta, Ga. bureau, responsible for primarily hard news coverage in the Southeastern United States and Central America. Reports appeared regularly on the TODAY SHOW, NBC Nightly News with Tom Brokaw, NBC Weekend News, and the NBC and The Source national radio networks. Also responsible for primary field-testing and implementation of the NBC News computer system. WPXI-TV (PITTSBURGH, PA.) Correspondent, 1976-1981. responsible for hard news coverage of local and statewide events, features and special series. Also produced, wrote and narrated national mini-documentary series syndicated for Cox Broadcasting and the NIWS News Service on international issues including the return of the Iranian hostages, the installation of Pope John Paul II, the rise of Solidarity in Poland and the ongoing civil war in Northern Ireland. WSOC-TV (CHARLOTTE, N.C.) Reporter, 1973-1976. Political and general assignments reporter. Morning and elections anchor. Freelance assignments for NBC News, Newsweek TV, United Press International Television, and the TVN international syndication service. ADDITIONAL EXPERIENCE INTELLIGENT MEDIA CONSULTANTS, LLC, 4/2000 - present. -

The Ethic of 'Free Advertising' and the Fourth Estate

The ethic of ‘free advertising’ and the Fourth Estate Author Ferguson, Anne Elizabeth Published 2006 Journal Title Australian Studies in Journalism Copyright Statement © The Author(s) 2006. The attached file is reproduced here in accordance with the copyright policy of the publisher. For information about this journal please refer to the journal’s website or contact the author. Downloaded from http://hdl.handle.net/10072/59992 Link to published version http://www.uq.edu.au/sjc/books-and-publications Griffith Research Online https://research-repository.griffith.edu.au The ethic of ‘free advertising’ and the Fourth Estate Anne Ferguson As public relations practitioners increasingly use new technologies to advance their agenda, could journalistic ethics and the role of the journalist in society become compromised? This paper explores the use of internet technology – in particular the emailing of media releases – by public relations practitioners, examining the gains for both public relations practitioner and journalist. This paper highlights increasing pressures faced by journalists that may allow public relations practitioners to achieve more than merely free advertising. Where do journalistic ethics come into play? This practice could not only challenge the media’s role as the Fourth Estate it could also allow public relations practitioners to become pseudo journalists and perhaps allow the news agenda to be set by public relations practitioners and those they represent. echnology has changed the way we look at the world. It has also changed the role of the journalist and just who is a T journalist. There has always been an issue about what constitutes a journalist but today anyone can write a blog, produce a video stream or even just post ideas on the web. -

Overview Not Confine the Discussion in This Report to Those Specific Issues Within the Commission’S Regulatory Jurisdiction

television, cable and satellite media outlets operate. Accordingly, we do Overview not confine the discussion in this report to those specific issues within the Commission’s regulatory jurisdiction. Instead, we describe below 1 MG Siegler, Eric Schmidt: Every 2 Days We Create As Much Information a set of inter-related changes in the media landscape that provide the As We Did Up to 2003, TECH CRUNCH, Aug 4, 2010, http://techcrunch. background for future FCC decision-making, as well as assessments by com/2010/08/04/schmidt-data/. other policymakers beyond the FCC. 2 Company History, THomsoN REUTERS (Company History), http://thom- 10 Founders’ Constitution, James Madison, Report on the Virginia Resolu- sonreuters.com/about/company_history/#1890_1790 (last visited Feb. tions, http://press-pubs.uchicago.edu/founders/documents/amendI_ 8, 2011). speechs24.html (last visited Feb. 7, 2011). 3 Company History. Reuter also used carrier pigeons to bridge the gap in 11 Advertising Expenditures, NEwspapER AssoC. OF AM. (last updated Mar. the telegraph line then existing between Aachen and Brussels. Reuters 2010), http://www.naa.org/TrendsandNumbers/Advertising-Expendi- Group PLC, http://www.fundinguniverse.com/company-histories/ tures.aspx. Reuters-Group-PLC-Company-History.html (last visited Feb. 8, 2011). 12 “Newspapers: News Investment” in PEW RESEARCH CTR.’S PRoj. foR 4 Reuters Group PLC (Reuters Group), http://www.fundinguniverse.com/ EXCELLENCE IN JOURNALISM, THE StatE OF THE NEws MEDIA 2010 (PEW, company-histories/Reuters-Group-PLC-Company-History.html (last StatE OF NEws MEDIA 2010), http://stateofthemedia.org/2010/newspa- visited Feb. 8, 2011). pers-summary-essay/news-investment/. -

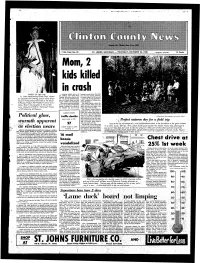

Kids Killed in Crash FAIREST of the FAIR a Lansing Mother and Two of Learned at Press Time

.-?*, --*--•. • ' *i»* ^. ;,i-r)iUA», ^ni^'^.u *. -«:^''WvS.' iii,i'f ;i,. j. ,\ .-,-. '-. V,,'.. .^ . ,* r t : &***;.* w-. 11.3th Year, No. 26 ST. JOHNS, MICHIGAN — THURSDAY,, OCTOBER 24, 1968 2 SECTIONS — 32 PAGES' 15 Cents Mom, 2 kids killed in crash FAIREST OF THE FAIR A Lansing mother and two of learned at press time. The little her children were killed early boy who was injured, however, St. Johns. Homecoming Queen Shari Uszew- Tuesday afternoon when the car. Is named Adam, and he Is about ski presented this striking picture while reign she was driving slammed into a 3 years old. He was reported in tree on Francis Road and split "fair" condition at Clinton Me ing over homecoming festivities at the dance' In half. Another son was injured. morial Hospital. following Friday's 46-7 football victory over •* The motherwasMrsLindaKay The triple fatality raised the, I I* Alma. Shari is the daughter of Mr and Mrs Catrl, 28, of 6300 S. Washington county's traffic death toll to 27, Avenue, Lansing. The names of about >340 per cent higher than A. A. Liszewsk'i of 205 W. McConnell Street. the children had not yet been at the same time lastyear. —CCN photo by Ed'Cheeney. The Clinton County Sheriff's Department was still tryihg to locate the husband and father of CLINTON COUNTY i the victims late Tuesday after noon in an effort to determine Political glow, traffic deaths which way Mrs Cairl might have — Clinton-County News oolorphoto fay Lowell G. Binker • i been driving. Her car hit a two- Since January 1, 1968 foot-in-diameter tree of thewest "•* - side of'Francis Road, about a Perfect autumn day for a field trip apparent half-mile south of M-21. -

Congressional Record United States Th of America PROCEEDINGS and DEBATES of the 109 CONGRESS, FIRST SESSION

E PL UR UM IB N U U S Congressional Record United States th of America PROCEEDINGS AND DEBATES OF THE 109 CONGRESS, FIRST SESSION Vol. 151 WASHINGTON, THURSDAY, APRIL 14, 2005 No. 44 Senate The Senate met at 9:30 a.m. and was U.S. SENATE, rights of individual Senators who feel called to order by the Honorable JOHN PRESIDENT PRO TEMPORE, they absolutely must address specific E. SUNUNU, a Senator from the State of Washington, DC, April 14, 2005. issues, but I continue to encourage New Hampshire. To the Senate: those who want to address immigration Under the provisions of rule I, paragraph 3, of the Standing Rules of the Senate, I hereby in a comprehensive way to do so at a PRAYER appoint the Honorable JOHN E. SUNUNU, a more appropriate time. The Chaplain, Dr. Barry C. Black, of- Senator from the State of New Hampshire, I know we can work out a process to fered the following prayer: to perform the duties of the Chair. keep moving forward on the emergency Let us pray. TED STEVENS, supplemental bill, but we have to ad- O God, who can test our thoughts and President pro tempore. dress specifically the range of immi- examine our hearts, look within our Mr. SUNUNU thereupon assumed the gration issues that have been brought leaders today and remove anything Chair as Acting President pro tempore. forth to the managers. The managers will continue to con- that will hinder Your Providence. Re- f sider the amendments that are brought place destructive criticism with kind- RECOGNITION OF THE MAJORITY forward. -

Public Affairs Broadcast Specialist/Chief Public Affairs NCO

*STP 46-46RZ14-SM-TG STP 46-46RZ14-SM-TG Soldier's Manual and Trainer's Guide PPUUBBLLIICC AAFFFFAAIIRRSS BBRROOAADDCCAASSTT SSPPEECCIIAALLIISSTT//CCHHIIEEFF PPUUBBLLIICC AAFFFFAAIIRRSS NNCCOO MOS 46R Skill Levels 1-3, MOS 46Z Skill Level 4 HEADQUARTERS, DEPARTMENT OF THE ARMY DECEMBER 2010 DISTRIBUTION RESTRICTION: Approved for public release; distribution is unlimited. i This publication is available at: Army Knowledge Online (www.us.army.mil) General Dennis J. Reimer Training and Doctrine Digital Library (http://www.train.army.mil) United States Army Publishing Directorate (http://www.apd.army.mil) *STP 46-46RZ14-SM-TG SOLDIER TRAINING HEADQUARTERS PUBLICATION DEPARTMENT OF THE ARMY No. 46-46RZ14-SM-TG Washington, D.C., 17 December 2010 SOLDIER'S MANUAL and TRAINER'S GUIDE MOS 46R/46Z Public Affairs Broadcast Specialist/Chief Public Affairs NCO Skill Levels 1, 2, 3 and 4 TABLE OF CONTENTS PAGE Table of Contents ......................................................................................................................................... i PREFACE ..................................................................................................................................................... v Chapter 1. Introduction ........................................................................................................................... 1-1 1-1. General ........................................................................................................................... 1-1 1-2. Training Overview ......................................................................................................... -

Section II: Strategic Writing in Public Relations

Section II: Strategic Writing in Public Relations I. Strategic Writing in Public Relations (pp. 41-42) 1. What is the definition of public relations? Public relations is the values-driven management of relationships with publics that are essential to an organization’s success. 2. Is public relations the same thing as publicity? Public relations certainly includes publicity (media relations)—but it includes much more, including employee relations. 3. What is the two-way symmetrical model of public relations? The two-way symmetrical model focuses on researching and communicating with target publics to build productive relationships that benefit both sides. In this model, the organization recognizes that sometimes it needs to change in order to build a productive relationship. II. News Release Guidelines (pp. 43-50) *Also see following sections. 1. Most news releases are written as ready-to-publish stories. Name two documents within the broad category of news releases that aren’t prepared in ready-to-publish formats. Answers could include social media news releases, media advisories and pitches. 2. What must the subject line in an e-mail news release do? A good subject line is newsworthy, specific and concise; it shows journalists that the related e-mail contains news of interest to their audiences. 3. In a good, newsworthy news release, the first sentence of the text covers – what? A good newsworthy first sentence often concisely covers who, what, when and where. III. Announcement News Releases (pp. 51-53) *Also see II above. 1. What is “inverted pyramid” organization? The lead (the opening paragraph) covers the most important aspects of who, what, where, when, why and how. -

The Dictionary Legend

THE DICTIONARY The following list is a compilation of words and phrases that have been taken from a variety of sources that are utilized in the research and following of Street Gangs and Security Threat Groups. The information that is contained here is the most accurate and current that is presently available. If you are a recipient of this book, you are asked to review it and comment on its usefulness. If you have something that you feel should be included, please submit it so it may be added to future updates. Please note: the information here is to be used as an aid in the interpretation of Street Gangs and Security Threat Groups communication. Words and meanings change constantly. Compiled by the Woodman State Jail, Security Threat Group Office, and from information obtained from, but not limited to, the following: a) Texas Attorney General conference, October 1999 and 2003 b) Texas Department of Criminal Justice - Security Threat Group Officers c) California Department of Corrections d) Sacramento Intelligence Unit LEGEND: BOLD TYPE: Term or Phrase being used (Parenthesis): Used to show the possible origin of the term Meaning: Possible interpretation of the term PLEASE USE EXTREME CARE AND CAUTION IN THE DISPLAY AND USE OF THIS BOOK. DO NOT LEAVE IT WHERE IT CAN BE LOCATED, ACCESSED OR UTILIZED BY ANY UNAUTHORIZED PERSON. Revised: 25 August 2004 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS A: Pages 3-9 O: Pages 100-104 B: Pages 10-22 P: Pages 104-114 C: Pages 22-40 Q: Pages 114-115 D: Pages 40-46 R: Pages 115-122 E: Pages 46-51 S: Pages 122-136 F: Pages 51-58 T: Pages 136-146 G: Pages 58-64 U: Pages 146-148 H: Pages 64-70 V: Pages 148-150 I: Pages 70-73 W: Pages 150-155 J: Pages 73-76 X: Page 155 K: Pages 76-80 Y: Pages 155-156 L: Pages 80-87 Z: Page 157 M: Pages 87-96 #s: Pages 157-168 N: Pages 96-100 COMMENTS: When this “Dictionary” was first started, it was done primarily as an aid for the Security Threat Group Officers in the Texas Department of Criminal Justice (TDCJ).