Here Should Add $36.00 for Postage

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

TOCC0362DIGIBKLT.Pdf

THÉODORE DUBOIS: CHAMBER MUSIC by William Melton (Clément-François) Théodore Dubois was born in Rosnay (Marne) on 24 August 1837 into an unmusical family. His father was in fact a basket-maker, but saw to it that a second-hand harmonium was purchased so that his son could receive his first music-lessons from the village cooper, M. Dissiry, an amateur organist. The pupil showed indications of strong musical talent and at the age of thirteen he was taken on by the maître de chapelle at Rheims Cathedral, Louis Fanart, a pupil of the noted composers Jean-François Lesueur and Alexandre-Étienne Choron (the boy made the ten-mile journey from home to Rheims and back each week on foot). When the Paris Conservatoire accepted Théodore as a student in 1853, it was the mayor of Rosnay, the Viscount de Breuil, who supplied the necessary funds (prompted by Théodore’s grandfather, a teacher who also served as secretary in the mayor’s office). While holding organ posts at Les Invalides and Sainte Clotilde, Dubois embraced studies with Antoine François Marmontel (piano), François Benoist (organ), François Bazin (harmony) and Ambroise Thomas (composition). Dubois graduated from the Conservatoire in 1861, having taken first prize in each of his classes. He also earned the Grand Prix de Rome with his cantata Atala, of which the Revue et Gazette musicale wrote: The cantata of M. Dubois is certainly one of the best we have heard. The poetic text of Roussy lacked strong dramatic situations but still furnished sufficient means for M. Dubois to display his real talent to advantage. -

5414939996535.Pdf

Manuel De Falla (1876 - 1946) El Amor Brujo - L’Amour Sorcier (1ère Version 1915) Cuadro primero El Retablo de Maese Pedro - Les Tréteaux 1. Introducción y Escena 2'48 de Ma tre Pierre 2. Canción del amor dolido 1'31 18. El pregón 0'54 3. Sortilegio 0'53 19. La sinfonía de Maese Pedro 3'09 4. Danza del fin del día (Danza ritual del fuego) 4'05 20. Cuadro I – La Corte de Carlo Magno 2'07 5. Escena (El amor vulgar) 1'08 21. Entrada de Carlo Magno 3'20 6. Romance del pescador 1'57 22. Cuadro II – Melisendra 4'15 7. Intermedio (Pantomima) 4'27 23. Cuadro III – El suplicio del Moro 1'18 24. Cuadro IV – Los Pirineos 6'47 Jean-François Heisser Cuadro segundo Cuadro V – La fuga direction et piano 8. Introducción (El Fuego fatuo) 1'03 Cuadro VI – la persecución 9. Escena (El terror) 1'12 25. Final 5'28 Antonia Contreras 10. Danza del Fuego fatuo (Danza del terror) 1'52 Cante / flamenco 11. Interludio (Alucinaciones) 1'42 durée totale : 76 minutes Jérôme Correas baryton 12. Canción del Fuego fatuo 2'22 « Don Quichotte » 13. Conjuro para reconquistar el amor perdido 2'48 Chantal Perraud soprano 14. Escena (El amor popular) 0'57 Chester Music « Le Truchement » 15. Danza y canción de la bruja fingida 4'12 Ed. Mario Bois / Paris Eric Huchet t é n o r 16. Final (las campanas del amanecer) 1'31 « Ma tre Pierre » Marie-Josèphe Jude piano 17. Fantasía Bætica - Fantaisie Bétique 13'46 Orchestre Poitou Charentes Céline Frisch clavecin El Amor Brujo L’Amour Sorcier Love the Magician Der Liebeszauber CUADRO PRIMERO 1. -

Quatuor Parisii

Parisii Quartet Founded by four students from the Conservatory of Paris, all first prize laureates in both instrument and chamber music, the Parisii Quartet recently celebrated its 30th anniversary. The keystone in their itinerary, the search of the perfect sound and profound conviction that music needs to be lived from the inside, is legated to the Parisii Quartet from its master, Maurice Crut, brilliant representative of the French-Belgian tradition and member of the renowned Pascal Quartet. The Melos, Amadeus and Lasalle Quartets, all contribute to the first edifying years of the Parisii Quartet, consecration of which is the prize winning of both the Evian and Munich Competitions in 1987. These victories open the door to the Quartet to the most prestigious chamber music series, and its performances attain over 100 concerts per year across 80 countries. Based on a shared ambition of excellence and eclecticism, over the years the Parisii musicians develop a repertoire of impressive breadth and unequalled quality of interpretation, undoubtedly placing them amongst the greatest. Convinced by the importance of supporting musical creation, the Parisii musicians actively contribute to reveal a number of contemporary composers. The Parisii Quartet’s discography faithfully reflects its musical itinerary, distinguishing itself for its breadth and eclecticism. While offering grand integrals such as Beethoven, Brahms and Webern, its first recordings are dedicated to the French repertoire (J. Ibert, A. Roussel, G. Tailleferre, G. Pierné, C. Franck, G. Fauré), over which the Quartet enjoys unanimous recognition throughout the world. Its discography also largely leaves room for a contemporary repertoire with numerous original works (G. -

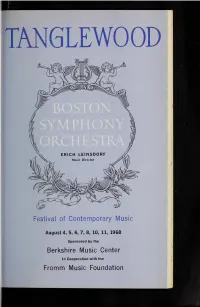

TANGLEWOOD ^Js M

TANGLEWOOD ^jS m ram? ' I'' Festival of Contemporary Music August 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 10, 11, 1968 Sponsored by the Berkshire Music Center In Cooperation with the Fromm Music Foundation What tomorrow Sa Be Li sounds like Ai M D Ei B: M Red Seal Albums Available Today Pi ELLIOTT CARTER: PIANO CONCERTO ^ML V< Lateiner, pianist * - ~t ^v, M Jaeob World Premiere Recorded Live M at Symphony Hall, Bostoe X MICHAEL C0L6RASS: AS QUIET AS CI GINASTERA ^ BOSTON SYMPHONY ERICH LEINSDORF * M Concerto for Piano and Orchest ra Steffi! *^^l !***" Br Variaciones Concertantes (1961) (Me^mdem^J&K^irai .55*4 EH Joao Carlos Martins. Pianist Bit* Ei Boston Symphony, ZTAcjlititcvicU o/'Oic/>e*tia& Erich Pa Leinsdori, Conductor St X; ''?£x£ k M Pa gir ' H ** IF ^^P^ V3 SEIJI OZAWA H at) STRAVINSKY wa Victor 5«sp JBT jaVicruit ; M AGON TURANGAlilA SYMPHONY SCHULLER k TAKEMITSU jKiWiB ^NOVEMBER 5TEP5^ 7 STUDIES on THEMES of PAUL KLEE Bk (First recording] . jn BOSTON SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA/ERICH LEINSDORF Wk. TORONTO Jm IV SYMPHONY^ ' ; Bfc* - * ^BIM ^JTeg X flititj g^M^HiH WKMi&aXi&i&X W Wt wnm :> ;.w%jii%. fl^B^^ ar ill THE VIRTUOSO SOUND of the ggS music pl CHICAGO SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA fornette JEAN MARTINON conductor fa coleman forms and sounds (recorded VARESE: ARCANA ' u live) as performed by the A. MARTIN: concerto for seven wind Philadelphia woodwind V quintet with interludes byornett* 198 INSTRUMENTS, TIMPANI, PERCUSSION m \ coleman SdilltS and ANO STRING ORCHESTRA Vsoldiers/space flight c \ ^mber { \ symphony of , I • 1 l _\. Philadelphia i-l. -

Mir034 Livret-1.Pdf

Manuel De Falla (1876 - 1946) El Amor Brujo - L’Amour Sorcier (1ère Version 1915) Cuadro primero El Retablo de Maese Pedro - Les Tréteaux 1. Introducción y Escena 2'48 de Maître Pierre 2. Canción del amor dolido 1'31 18. El pregón 0'54 3. Sortilegio 0'54 19. La sinfonía de Maese Pedro 3'10 4. Danza del fin del día (Danza ritual del fuego) 4'05 20. Cuadro I – La Corte de Carlo Magno 2'07 5. Escena (El amor vulgar) 1'08 21. Entrada de Carlo Magno 3'21 6. Romance del pescador 1'57 22. Cuadro II – Melisendra 4'15 7. Intermedio (Pantomima) 4'27 23. Cuadro III – El suplicio del Moro 1'19 24. Cuadro IV – Los Pirineos 6'46 Jean-François Heisser Cuadro segundo Cuadro V – La fuga direction et piano 8. Introducción (El Fuego fatuo) 1'03 Cuadro VI – la persución 9. Escena (El terror) 1'12 25. Final 5'29 Antonia Contreras 10. Danza del Fuego fatuo (Danza del terror)w 1'52 Cante / flamenco 11. Interludio (Alucinaciones) 1'43 durée totale : 76 minutes Jérôme Correas baryton 12. Canción del Fuego fatuo 2'22 « Don Quichotte » 13. Conjuro para reconquistar el amor perdido 2'48 Chantal Perraud soprano 14. Escena (El amor popular) 0'57 Chester Music « Le Truchement » 15. Danza y canción de la bruja fingida 4'12 Ed. Mario Bois / Paris Eric Huchet t é n o r 16. Final (las campanas del amanecer) 1'21 « Ma tre Pierre » Marie-Joseph Jude piano 17. Fantasía Bætica - Fantasie Bétique 13'38 Orchestre Poitou Charentes Céline Frisch clavecin El Amor Brujo L’Amour Sorcier Love the Magician Der Liebeszauber CUADRO PRIMERO 1. -

Journal of the American Viola Society Volume 17 No. 2, 2001

J OURNAL "' . ·--.-.... .. of the .-r....... ~- . . .:- • ~· .. ·~ .. · f -.. Al\4ERICAN VIOLA SOCIETY Vol. 17 No. 2 FEATURES 15 An Overview ofTwentieth-Century Viola Works, Part II By Jacob Glick -I .• 21 The Basics Revisited: Artistic Distinctions "Flexibility of Vibrato: Controlling Width and Speed" By Heidi Castleman .. 29 An Interview with Steven R Gerber By jeffrey fames 39 Report on the Violin Society of America's 14th Annual Competition for Instrument Making By Christine Rutledge ·.-· ... ... 45 2001 Primrose Memorial Scholarship Competition By Kathryn Steely • • •• .. OFFICERS Peter Slowik President Profossor o[Viola Oberlin College Conservatory 13411 Compass Point Strongsville, OH 44136 peter.slowik@oberlin. edu I William Preucil Vice President 317 Windsor Dr. Iowa City, /A 52245 Catherine Forbes Secretary 1128 Woodland Dr. Arlington, TX 76012 Ellen Rose Treasurer 2807 Lawtherwood Pl. Dallas, TX 75214 Thomas Tatton Past President 7511 Parkwoods Dr. Stockton, CA 95207 BOARD Victoria Chiang Donna Lively Clark Paul Coletti Ralph Fielding Pamela Goldsmith john Graham - -~_-·-· -~E~I Barbara Hamilton Karen Ritscher Christine Rutledge -__ -==~~~ Kathryn Steely juliet White-Smith Louise Zeitlin EDITOR, JAVS Kathryn Steely Baylor University P.O. Box 97408 Woco, TX 76798 PAST PRESIDENTS Myron Rosenblum (1971-1981) Maurice W Riley (1981-1986) David Dalton (1986-1990) Alan de Veritch (1990-1994) HONORARY PRESIDENT William Primrose (deceased) oftf:Y Section ofthe International Viola Society The journal ofthe American Viola Society is a peer-reviewed publication of that organization and is produced at A-R Editions in Middleton, Wisconsin. © 2001, American Viola Society ISSN 0898-5987 ]AVS welcomes letters and articles from its readers. Editor: Kathryn Steely Assistant Editor: Jeff A. -

AMERICAN and ESTONIAN CONTEMPORARY MUSIC Compositions by Pozzi Escot, Robert Cogan, Helena Tulve, Mari Vihmand

„Music and Environment“, April, 23–25, 2009 Tallinn University, Institute of Fine Arts, Music Department, Lai Street 13, 10133, Tallinn www.tlu.ee/CFME09 FRIDAY APRIL 24, 2009 CONCERT AND PRESENTATION-WORKSHOP AMERICAN AND ESTONIAN CONTEMPORARY MUSIC Compositions by Pozzi Escot, Robert Cogan, Helena Tulve, Mari Vihmand Presentation-workshop 11.15–12.00 Jon Sakata, Jung Mi Lee & Joan Heller Lai street 13 L-208 "Music and Memory: Creative Experimentation towards a new Mental Ecology" Compositions by Pozzi Escot and Robert Cogan Concert: American and Estonian Contemporary Music 17.30–19.00 Pozzi Escot, Robert Cogan, Helena Tulve, Mari Vihmand Lai street 13 L-208 Within the 2nd International Conference CFME09 we are glad to present the amazing oevre of two of the main keynote speakers of the conference Prof. Robert Cogan and Prof. Pozzi Escot (New England Conservatory, Boston, USA). Both are outstanding personalities in the field of composing as well as music theory, pedagogics and music writing. The concert will be enriched by the music of two outstanding Estonian contemporary composers Mari Vihmand and Helena Tulve. The event is sponsored by US-Embassy Estonia, Southern Methodist University Dallas and New England Conservatory Boston. Many thanks goes to the composers and performers for their personal benefit and effort. PROGRAM 1. Sonatina IV (1992) Pozzi Escot Jung Mi Lee, piano Jon Sakata, piano 2. Eskiis 02 (2002) Mari Vihmand Jon Sakata, piano 3. Aria II (2001, with pre-recorded tape) Pozzi Escot Joan Heller, voice 4. Contexts/Memories Version C Robert Cogan Jung Mi Lee, piano Jon Sakata, piano INTERMISSION 5. -

March 16, 2008 2666Th Concert

For the convenience of concertgoers the Garden Cafe remains open until 6:oo pm. The use of cameras or recording equipment during the performance is not allowed. Please be sure that cell phones, pagers, and other electronic devices are turned off. Please note that late entry or reentry of The Sixty-sixth Season of the West Building after 6:30 pm is not permitted. The William Nelson Cromwell and F. Lammot Belin Concerts National Gallery of Art 2,666th Concert Music Department National Gallery of Art Parisii Quartet Sixth Street and Constitution Avenue nw Arnaud Vallin and Jean-Michel Berrette, violin Washington, DC Dominique Lobet, viola Jean-Philippe Martignoni, cello Mailing address 2000b South Club Drive With Landover, md 20783 Jerome Correas, baritone wiviv.ngfl.gov Emmanuel Strosser, pianist March 16, 2008 Sunday Evening, 6:30 pm West Building, West Garden Court Admission free Program Germaine Tailleferre (1892-1983) String Quartet (1917-1919) Modere Intermede Final Maurice Ravel (1875-1937) Don Quichotte a Dulcinee Chanson romanesque Chanson epique Chanson a boire Reynaldo Hahn (1875-1947) Presented in honor of the exhibition Quintet in F-sharp Minor for Piano and Strings In the Forest of Fontainebleau: Molto agitato e con fuoco Andante (non troppo lento) Painters and Photographers from Corot to Monet Allegretto grazioso INTERMISSION Gabriel Faure (1845-1924) La Bonne chanson For baritone, piano, and string quartet Une sainte en son aureole Puisque l’aube grandit La lune blanche luit dans les bois J'allais par des chemins perfides J’ai presque peur, en verite Avant que tu ne fen ailles Done, ce sera par un clair jour d’ete N’est-ce pas? L’hiver a cesse The Musicians Pianist Emmanuel Strosser began his musical studies at the age of six with Helene Boschi in his native town of Strasbourg, France. -

NATIONAL GALLERY ORCHESTRA PERSONNEL, 1988-89 George Manos, Conductor the F

NATIONAL GALLERY ORCHESTRA PERSONNEL, 1988-89 George Manos, Conductor THE F. LAMMOT BELIN CONCERTS Violins Lily Kramer Flutes Priscilla Fritter Judith Parkinson John Lagerquist Cynthia Montooth Stephani Stang/McCusker National Gallery of Art Melissa Graybeal Shin-yeh Lu Oboes Gene Montooth Patricia Cochran Carole Libelo Mary Price Kathleen Golding Roger Weiler Clarinets Merlin Petroff Victoria Noyes Charles Hite Cynthia Mauney Stephen Bates Sarah Botti Eugene Dreyer Bassoons James Bolyard Maurice Myers Donald Shore Lawrence Wallace Nancy Stutsman Delores Robbins Horns Gregory Drone Robert Spates Carolyn Parks Timothy Macek Amy O’George Douglas Dube Virginia Day Linda Leanza Trumpets Dennis Edelbrock Violas Shelly Coss Robert Hazen Evelyn Harpham Christopher Tranchitella Carl Rubis Trombones Edward Kiehl Barbara Winslow Donald King George Ohlson David Summers David Basch Tuba Michael Bunn Cellos Robert Newkirk David Premo Timpani Ronald Barnett Forty-sixth American Music Festival Jean Robbins Helen Coffman Percussion Albert Merz Under the Direction of George Manos Carla Rosenberg William Richards Thomas Jones Basses John Ricketts Harp Rebecca A. Smith Norman Irvine Mark Stephenson Organ and Harpsichord Stephen Ackert Eugene Dreyer, Personnel Manager O O O O CONCERTS IN JUNE, 1989 Sunday Evenings, April 2 through May 28, 1989 4 Weekley and Arganbright, piano duo 11 Nana Mukhadze, piano at Seven O’clock 18 Paul Maillet, piano West Building, West Garden Court 25 National Gallery Orchestra, George Manos, Conductor Open to the public, free of charge 1927th Concert —April 2, 1989 Conductor, composer and pianist GEORGE MANOS has been Director of NATIONAL GALLERY ORCHESTRA Music at the National Gallery and Artistic Director of the Gallery’s American Music Festival since 1985. -

Affirming Richard Wilson 11 DAVID CLEARY

21ST CENTURY MUSIC APRIL 2001 INFORMATION FOR SUBSCRIBERS 21ST-CENTURY MUSIC is published monthly by 21ST-CENTURY MUSIC, P.O. Box 2842, San Anselmo, CA 94960. Subscription rates in the U.S. are $84.00 (print) and $42.00 (e-mail) per year; subscribers to the print version elsewhere should add $36.00 for postage. Single copies of the current volume and back issues are $8.00 (print) and $4.00 (e-mail) Large back orders must be ordered by volume and be pre-paid. Please allow one month for receipt of first issue. Domestic claims for non-receipt of issues should be made within 90 days of the month of publication, overseas claims within 180 days. Thereafter, the regular back issue rate will be charged for replacement. Overseas delivery is not guaranteed. Send orders to 21ST-CENTURY MUSIC, P.O. Box 2842, San Anselmo, CA 94960. e-mail: [email protected]. Typeset in Times New Roman. Copyright 2001 by 21ST-CENTURY MUSIC. This journal is printed on recycled paper. Copyright notice: Authorization to photocopy items for internal or personal use is granted by 21ST-CENTURY MUSIC. INFORMATION FOR CONTRIBUTORS 21ST-CENTURY MUSIC invites pertinent contributions in analysis, composition, criticism, interdisciplinary studies, musicology, and performance practice; and welcomes reviews of books, concerts, music, recordings, and videos. The journal also seeks items of interest for its calendar, chronicle, comment, communications, opportunities, publications, recordings, and videos sections. Typescripts should be double-spaced on 8 1/2 x 11 -inch paper, with ample margins. Authors with access to IBM compatible word-processing systems are encouraged to submit a floppy disk, or e-mail, in addition to hard copy. -

Words on Music, Perhaps: the Writings of Arthur Berger

ABSTRACT Title of Dissertation: WORDS ON MUSIC, PERHAPS: THE WRITINGS OF ARTHUR BERGER Jennifer Miriam Kobuskie, Doctor of Philosophy, 2020 Dissertation directed by: Olga Haldey, Associate Professor, Musicology and Ethnomusicology Division, School of Music When Arthur Berger (1912–2003) is mentioned in the history books, it is often as a mid-20th century American composer, or a practitioner and teacher of music theory who, during his tenure at Brandeis University, had trained a generation of theorists and composers. This dissertation aims to demonstrate that Berger made one of his most significant contributions to the history of 20th-century music as a writer of prose. As a full-time critic, his work was featured in major newspapers of New York and Boston, and nationally distributed periodicals. He helped found two music journals, contributed regularly to others, and authored two books. For decades, his voice was widely heard and broadly influential. His aesthetic views, stated boldly and unapologetically, helped shape the post-WWII discourse on modern, particularly American music, and continue to impact both public and scholarly debate on this topic. This study surveys Berger’s personal history as a writer, including his career as a music critic, his involvement with the creation of the scholarly journal Perspectives of New Music, his pioneering biography of Aaron Copland, and his seminal article on Stravinsky’s octatonicism. The dissertation also offers a detailed, comprehensive analysis of Berger’s voluminous corpus of writings, both published and unpublished, as well as his personal archive of notes, drafts, and correspondence, in order to elucidate his aesthetic principles, and his views on a broad variety of subjects related to modern music, such as neoclassicism, nationalism, innovation and tradition, the music of Stravinsky, Copland, and their American successors, as well as the role of classical music in American culture, and the place of American music in the world. -

Download Booklet

559618 bk Gerber US 6/4/09 09:47 Page 8 Sara Davis Buechner AMERICAN CLASSICS The pianist Sara Davis Buechner is a Bronze Medalist of the 1986 Tchaikovsky International Piano Competition in Moscow. With an active repertoire of over a hundred piano concertos ranging from Albéniz to Zimbalist, she has appeared as soloist with North America’s most prominent orchestras and tours widely throughout the Far East on a yearly Steven R. basis. She has collaborated in many celebrated recordings on the Connoisseur Society and Koch International labels, as well as a library of Yamaha Disklavier files, and has Photo: Peter Schaaf performed and commissioned many new works by composers such as Dorothy Chang, Stephen Chatman, Pierre Charvet, Dick Hyman, Henry Martin, Paul Moravec, Yukiko GERBER Nishimura and Charles Wuorinen. She actively appears in collaborations with film and dance at venues such as Lincoln Center and with the Mark Morris Dance Group. Sara Davis Buechner is Associate Professor of Music at the University of British Columbia in Vancouver, and formerly served on the piano faculty of New York University. She has given many master-classes internationally, and her popularity in Japan has led to her Piano Trio becoming an Honorary Member of the Hanshin Tigers baseball team of Osaka. Duo • Elegy Notturno Kurt Nikkanen, Violin and Viola Cho-Liang Lin, Violin Cyrus Beroukhim, Violin Brinton Smith, Cello Sara Davis Buechner, Piano 8.559618 8 559618 bk Gerber US 6/4/09 09:47 Page 2 Steven R. Cyrus Beroukhim GERBER Violinist Cyrus Beroukhim has received international recognition as a soloist, recitalist and chamber musician, and has appeared at major venues worldwide.