Language Contact in North Sulawesi: Preliminary Observations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Use Style: Paper Title

1st International Conference on Social Sciences (ICSS 2018) Social Science and Humanities for Sustainable Development to Support Community Empowerment Advances in Social Science, Education and Humanities Research Volume 226 Kuta Selatan, Indonesia 18 – 19 October 2018 Part 1 of 2 Editors: Andre Dwijanto Witjaksono Rojil Nugroho Bayu Aji Danang Tandyonomanu Dian Ayu Larasati A. Octamaya Tenri Awaru Iman Pasu M. H. Purba Theodorus Pangalila Galih Wahyu Pradana Tsuroyya Agus Machfud Fauzi Yuni Lestari ISBN: 978-1-5108-9881-3 Printed from e-media with permission by: Curran Associates, Inc. 57 Morehouse Lane Red Hook, NY 12571 Some format issues inherent in the e-media version may also appear in this print version. Copyright© (2018) by Atlantis Press All rights reserved. Copyright for individual electronic papers remains with the authors. For permission requests, please contact the publisher: Atlantis Press Amsterdam / Paris Email: [email protected] Conference Website: http://www.atlantis-press.com/php/pub.php?publication=icss-18 Printed with permission by Curran Associates, Inc. (2020) Additional copies of this publication are available from: Curran Associates, Inc. 57 Morehouse Lane Red Hook, NY 12571 USA Phone: 845-758-0400 Fax: 845-758-2633 Email: [email protected] Web: www.proceedings.com TABLE OF CONTENTS PART 1 SESSION: KEYNOTE SOCIAL SCIENCES AND THE INDONESIAN HISTORICAL DIASPORA ................................................................1 David Reeve BEST PRACTICES FOR SOCIAL MEDIA GOVERNANCE AND STRATEGY AT THE -

Local Languages, Local Malay, and Bahasa Indonesia a Case Study from North Maluku

PB Wacana Vol. 14 No. 2 (October 2012) JOHN BOWDENWacana, Local Vol. 14languages, No. 2 (October local Malay, 2012): and 313–332 Bahasa Indonesia 313 Local languages, local Malay, and Bahasa Indonesia A case study from North Maluku JOHN BOWDEN Abstract Many small languages from eastern Indonesia are threatened with extinction. While it is often assumed that ‘Indonesian’ is replacing the lost languages, in reality, local languages are being replaced by local Malay. In this paper I review some of the reasons for this in North Maluku. I review the directional system in North Maluku Malay and argue that features like the directionals allow those giving up local languages to retain a sense of local linguistic identity. Retaining such an identity makes it easier to abandon local languages than would be the case if people were switching to ‘standard’ Indonesian. Keywords Local Malay, language endangerment, directionals, space, linguistic identity. 1 Introduction Maluku Utara is one of Indonesia’s newest and least known provinces, centred on the island of Halmahera and located between North Sulawesi and West Papua provinces. The area is rich in linguistic diversity. According to Ethnologue (Lewis 2009), the Halmahera region is home to seven Austronesian languages, 17 non-Austronesian languages and two distinct varieties of Malay. Although Maluku Utara is something of a sleepy backwater today, it was once one of the most fabled and important parts of the Indonesian archipelago and it became the source of enormous treasure for outsiders. Its indigenous clove crop was one of the inspirations for the great European age of discovery which propelled navigators such as Christopher Columbus and Ferdinand Magellan to set forth on their epic journeys across the globe. -

Legal Testing on Hate Speech Through Social Media

Advances in Social Science, Education and Humanities Research, volume 226 1st International Conference on Social Sciences (ICSS 2018) Legal Testing on Hate Speech Through Social Media 1st Erni Dwita Silambi 2nd Yuldiana Zesa Azis 3rd Marlyn Jane Alputila Law of Science Department, Law of Science Department, Law of Science Department, Faculty of Law Faculty of Law Faculty of Law Universitas Musamus Universitas Musamus Universitas Musamus Merauke, Indonesia Merauke, Indonesia Merauke, Indonesia [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] 4th Dina Fitri Septarini .rs Name/s per 2nd Affiliation Accounting Department, Faculty of Economy and Business, Universitas Musamus Merauke, Indonesia [email protected] . name of or Abstract— The rapid growth of technology, including in the also found that there was a difference between B2B and B2C internet, has led to an increase in crime. This study aims to find companies, which confirmed the significant impact between out the laws carried out by the police at Merauke Regional Police B2C companies on LinkedIn and stock returns. This finding is in enforcing Hate Speech Crime on social media 2. To find out useful for company managers and social media activists who the inhibiting factors in enforcing Hate Speech on social media. try to understand the impact of social media finance on This research was conducted in Merauke Regency, Papua Indonesia in 2018. This research method is conducted using company value [1]. qualitative methods that collect by conducting interviews and literature studies. This study shows that: 1. Repetition and Social media is a site that provides a place for users to handling of hate speech The police conduct prevention and interact online. -

Manado Malay: Features, Contact, and Contrasts. Timothy Brickell: [email protected]

Manado Malay: features, contact, and contrasts. Timothy Brickell: [email protected] Second International Workshop on Malay varieties: ILCAA (TUFS) 13th-14th October 2018 Timothy Brickell: [email protected] Introduction / Acknowledgments: ● Timothy Brickell – B.A (Hons.): Monash University 2007-2011. ● PhD: La Trobe University 2011-2015. Part of ARC DP 110100662 (CI Jukes) and ARC DECRA 120102017 (CI Schnell). ● 2016 – 2018: University of Melbourne - CI for Endangered Languages Documentation Programme/SOAS IPF 0246. ARC Center of Excellence for the Dynamics of Language (CoEDL) affiliate. ● Fieldwork: 11 months between 2011-2014 in Tondano speech community. 8 months between 2015-2018 in Tonsawang speech community. ● October 2018 - :Endeavour Research Fellowship # 6289 (thank you to Assoc. Prof. Shiohara and ILCAA at TUFS for hosting me). Copyrighted materials of the author PRESENTATION OVERVIEW: ● Background: brief outline of linguistic ecology of North Sulawesi. Background information on Manado Malay. ● Outline of various features of MM: phonology, lexicon, some phonological changes, personal pronouns, ordering of elements within NPs, posessession, morphology, and causatives. ● Compare MM features with those of two indigenous with which have been in close contact with MM for at least 300 years - Tondano and Tonsawang. ● Primary questions: Has long-term contact with indigneous languages resulted in any shared features? Does MM demonstrate structural featues (Adelaar & Prentice 1996; Adelaar 2005) considered characteristic of contact Malay varities? Background:Geography ● Minahasan peninsula: northern tip of Sulawesi, Indonesia. Background: Indigenous language groups ● Ten indigenous language micro-groups of Sulawesi (Mead 2013:141). Approx. 114 languages in total (Simons & Fennings 2018) North Sulawesi indigenous language/ethnic groups: Languages spoken in North Sulawesi: Manado Malay (ISO 639-3: xmm) and nine languages from three microgroups - Minahasan (five), Sangiric (three), Gorontalo-Mongondow (one). -

Papuan Malay – a Language of the Austronesian- Papuan Contact Zone

Journal of the Southeast Asian Linguistics Society JSEALS 14.1 (2021): 39-72 ISSN: 1836-6821, DOI: http://hdl.handle.net/10524/52479 University of Hawaiʼi Press PAPUAN MALAY – A LANGUAGE OF THE AUSTRONESIAN- PAPUAN CONTACT ZONE Angela Kluge SIL International [email protected] Abstract This paper describes the contact features that Papuan Malay, an eastern Malay variety, situated in East Nusantara, the Austronesian-Papuan contact zone, displays under the influence of Papuan languages. This selection of features builds on previous studies that describe the different contact phenomena between Austronesian and non-Austronesian languages in East Nusantara. Four typical western Austronesian features that Papuan Malay is lacking or making only limited use of are examined in more detail: (1) the lack of a morphologically marked passive voice, (2) the lack of the clusivity distinction in personal pronouns, (3) the limited use of affixation, and (4) the limited use of the numeral-noun order. Also described in more detail are six typical Papuan features that have diffused to Papuan Malay: (1) the genitive-noun order rather than the noun-genitive order to express adnominal possession, (2) serial verb constructions, (3) clause chaining, and (4) tail-head linkage, as well as (5) the limited use of clause-final conjunctions, and (6) the optional use of the alienability distinction in nouns. This paper also briefly discusses whether the investigated features are also present in other eastern Malay varieties such as Ambon Malay, Maluku Malay and Manado Malay, and whether they are inherited from Proto-Austronesian, and more specifically from Proto-Malayic. By highlighting the unique features of Papuan Malay vis-à-vis the other East Nusantara Austronesian languages and placing the regional “adaptations” of Papuan Malay in a broader diachronic perspective, this paper also informs future research on Papuan Malay. -

Iouo Iouo Iouo Iouo Iouo Iouo Iouo Iouo Iouo Iouo Iouo Iouo Iouo Iouo Iouo Iouo Iouo Iouo Iouo Iouo Iouo Iouo Iouo Iouo Iouo

Asia No. Language [ISO 639-3 Code] Country (Region) 1 A’ou [aou] Iouo China 2 Abai Sungai [abf] Iouo Malaysia 3 Abaza [abq] Iouo Russia, Turkey 4 Abinomn [bsa] Iouo Indonesia 5 Abkhaz [abk] Iouo Georgia, Turkey 6 Abui [abz] Iouo Indonesia 7 Abun [kgr] Iouo Indonesia 8 Aceh [ace] Iouo Indonesia 9 Achang [acn] Iouo China, Myanmar 10 Ache [yif] Iouo China 11 Adabe [adb] Iouo East Timor 12 Adang [adn] Iouo Indonesia 13 Adasen [tiu] Iouo Philippines 14 Adi [adi] Iouo India 15 Adi, Galo [adl] Iouo India 16 Adonara [adr] Iouo Indonesia Iraq, Israel, Jordan, Russia, Syria, 17 Adyghe [ady] Iouo Turkey 18 Aer [aeq] Iouo Pakistan 19 Agariya [agi] Iouo India 20 Aghu [ahh] Iouo Indonesia 21 Aghul [agx] Iouo Russia 22 Agta, Alabat Island [dul] Iouo Philippines 23 Agta, Casiguran Dumagat [dgc] Iouo Philippines 24 Agta, Central Cagayan [agt] Iouo Philippines 25 Agta, Dupaninan [duo] Iouo Philippines 26 Agta, Isarog [agk] Iouo Philippines 27 Agta, Mt. Iraya [atl] Iouo Philippines 28 Agta, Mt. Iriga [agz] Iouo Philippines 29 Agta, Pahanan [apf] Iouo Philippines 30 Agta, Umiray Dumaget [due] Iouo Philippines 31 Agutaynen [agn] Iouo Philippines 32 Aheu [thm] Iouo Laos, Thailand 33 Ahirani [ahr] Iouo India 34 Ahom [aho] Iouo India 35 Ai-Cham [aih] Iouo China 36 Aimaq [aiq] Iouo Afghanistan, Iran 37 Aimol [aim] Iouo India 38 Ainu [aib] Iouo China 39 Ainu [ain] Iouo Japan 40 Airoran [air] Iouo Indonesia 1 Asia No. Language [ISO 639-3 Code] Country (Region) 41 Aiton [aio] Iouo India 42 Akeu [aeu] Iouo China, Laos, Myanmar, Thailand China, Laos, Myanmar, Thailand, -

Research Note

Research Note The Austronesian Comparative Dictionary: A Work in Progress Robert Blust and Stephen Trussel UNIVERSITY OF HAWAI‘I AT MĀNOA AND TRUSSEL SOFTWARE DEVELOPMENT The Austronesian comparative dictionary (ACD) is an open-access online resource that currently (June 2013) includes 4,837 sets of reconstructions for nine hierarchically ordered protolanguages. Of these, 3,805 sets consist of single bases, and the remaining 1,032 sets contain 1,032 bases plus 1,781 derivatives, including affixed forms, reduplications, and compounds. His- torical inferences are based on material drawn from more than 700 attested languages, some of which are cited only sparingly, while others appear in over 1,500 entries. In addition to its main features, the ACD contains sup- plementary sections on widely distributed loanwords that could potentially lead to erroneous protoforms, submorphemic “roots,” and “noise” (in the information-theoretic sense of random lexical similarity that arises from historically independent processes). Although the matter is difficult to judge, the ACD, which prints out to somewhat over 3,000 single-spaced pages, now appears to be about half complete. 1. INTRODUCTION. 1 The December 2011 issue of this journal carried a Research Note that described the history and present status of POLLEX, the Polynesian Lexicon project initiated by the late Bruce Biggs in 1965, which over time has grown into one of the premier comparative dictionaries available for any language family or major subgroup (Greenhill and Clark 2011). A theme that runs through this piece is the remark- able growth over the 46 years of its life (at that time), not just in the content of the dictio- nary, but in the technological medium in which the material is embedded. -

The Minahasan Languages = De Minahasische Talen

The Minahasan languages by Nicolaus Adriani translated by David Mead 2020 Sulang Language Data and Working Papers: Translations from the Dutch, no. 24 Sulawesi Language Alliance http://sulang.org/ SulangTrans024-v1 LANGUAGES Subject language : Tombulu, Tondano, Tonsea, Tonsawang, Tontemboan Language of materials : English DESCRIPTION The author begins this paper with an enumeration of the ten languages spoken within the geographical boundaries of the Minahasan Residency located at the northern tip of Celebes (Sulawesi). Thereafter he concentrates on the five Minahasan languages proper, discussing the basis first for their inclusion in a Philippine language group, and second for their internal division into two groups, one comprising Tombulu’, Tonsea’ and Tondano, the other Tontemboan and Tonsawang. This is followed by a lengthy review of Tontemboan literature, including synopses of a number of folktales. The author considered all five Minahasan languages to be threatened, and closes with an appeal for similar work to be carried out in the other languages. A bibliography comprehensively lists previously published works concerning the Minahasan languages. SOURCE Adriani, N. 1925. De Minahasische talen. Bijdragen tot de Taal-, Land- en Volkenkunde van Nederlandsch-Indië 81:134–164. Original pagination is indicated by including the page number in square brackets, e.g. [p. 134]. VERSION HISTORY Version 1 [25 September 2020] © 2020 by David Mead All Rights Reserved [p. 134] FROM AND ABOUT THE MINAHASA. III. THE MINAHASAN LANGUAGES. BY DR. N. ADRIANI The Minahasa as a whole, with the islands that belong to it, is not occupied exclusively by the Minahasan languages. Although its territory is already not extensive, it further yields a small part to five non-Minahasan languages: Sangir, Bentenan, Bantik, Ponosakan and Bajo. -

World Languages Using Latin Script

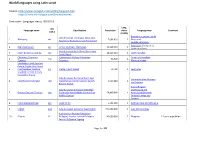

World languages using Latin script Source: http://www.omniglot.com/writing/langalph.htm https://www.ethnologue.com/browse/names Sort order : Language status, ISO 639-3 Lang, ISO Language name Classification Population status Language map Comment 639-3 (EGIDS) Botswana, Lesotho, South Indo-European, Germanic, West, Low 1. Afrikaans, afr 7,096,810 1 Africa and Saxon-Low Franconian, Low Franconian SwazilandNamibia Azerbaijan,Georgia,Iraq 2. Azeri,Azerbaijani azj Turkic, Southern, Azerbaijani 24,226,940 1 Jordan and Syria Indo-European Balto-Slavic Slavic West 3. Czech Bohemian Cestina ces 10,619,340 1 Czech Republic Czech-Slovak Chamorro,Chamorru Austronesian Malayo-Polynesian Guam and Northern 4. cha 94,700 1 Tjamoro Chamorro Mariana Islands Seychelles Creole,Seselwa Creole, Creole, Ilois, Kreol, 5. Kreol Seselwa, Seselwa, crs Creole, French based 72,700 1 Seychelles Seychelles Creole French, Seychellois Creole Indo-European Germanic North East Denmark Finland Norway 6. DanishDansk Rigsdansk dan Scandinavian Danish-Swedish Danish- 5,520,860 1 and Sweden Riksmal Danish AustriaBelgium Indo-European Germanic West High Luxembourg and 7. German Deutsch Tedesco deu German German Middle German East 69,800,000 1 NetherlandsDenmark Middle German Finland Norway and Sweden 8. Estonianestieesti keel ekk Uralic Finnic 1,132,500 1 Estonia Latvia and Lithuania 9. English eng Indo-European Germanic West English 341,000,000 1 over 140 countries Austronesian Malayo-Polynesian 10. Filipino fil Philippine Greater Central Philippine 45,000,000 1 Filippines L2 users population Central Philippine Tagalog Page 1 of 48 World languages using Latin script Lang, ISO Language name Classification Population status Language map Comment 639-3 (EGIDS) Denmark Finland Norway 11. -

Stress Predictors in a Papuan Malay Random Forest

STRESS PREDICTORS IN A PAPUAN MALAY RANDOM FOREST Constantijn Kaland1, Nikolaus P. Himmelmann1, Angela Kluge2 1Institute of Linguistics, University of Cologne, Germany 2SIL International {ckaland, sprachwissenschaft}@uni-koeln.de, [email protected] ABSTRACT penultimate syllable. This distribution makes Papuan Malay similar to other Trade Malay varieties [16] The current study investigates the phonological where stress has been reported to be mostly factors that determine the location of word stress in penultimate; e.g. Manado [25], Kupang [23], Papuan Malay, an under-researched language Larantuka [12] and the North Moluccan varieties spoken in East-Indonesia. The prosody of this Tidore [30] and Ternate [14]. Similarly, varieties of language is poorly understood, in particular the use Indonesian have been analysed as having of word stress. The approach taken here is novel in penultimate stress. Work on Indonesian has shown that random forest analysis was used to assess which the importance of distinguishing language varieties. factors are most predictive for the location of stress Where Toba Batak listeners rated manipulated stress in a Papuan Malay word. The random forest analysis cues as less acceptable when these did not occur on was carried out with a set of 17 potential word stress the penultimate syllable, Javanese listeners had no predictors on a corpus of 1040 phonetically preference whatsoever [4]. transcribed words. A complementary analysis of As for the Trade Malay varieties, Ambonese word stress distributions was done in order to derive appeared to not make use of word stress [15], a set of phonological criteria. Results show that with counter to earlier claims [29]. -

On the Perception of Prosodic Prominences and Boundaries in Papuan Malay

Chapter 13 On the perception of prosodic prominences and boundaries in Papuan Malay Sonja Riesberg Universität zu Köln & Centre of Excellence for the Dynamics of Language, The Australian National University Janina Kalbertodt Universität zu Köln Stefan Baumann Universität zu Köln Nikolaus P. Himmelmann Universität zu Köln This paper reports the results of two perception experiments on the prosody ofPapuan Malay. We investigated how native Papuan Malay listeners perceive prosodic prominences on the one hand, and boundaries on the other, following the Rapid Prosody Transcription method as sketched in Cole & Shattuck-Hufnagel (2016). Inter-rater agreement between the participants was shown to be much lower for prosodic prominences than for boundaries. Importantly, however, the acoustic cues for prominences and boundaries largely overlap. Hence, one could claim that inasmuch as prominence is perceived at all in Papuan Malay, it is perceived at boundaries, making it doubtful whether prosodic prominence can be usefully distinguished from boundary marking in this language. Our results thus essentially confirm the results found for Standard Indonesian by Goedemans & van Zanten (2007) and vari- ous claims regarding the production of other local varieties of Malay; namely, that Malayic varieties appear to lack stress (i.e. lexical stress as well as post-lexical pitch accents). Sonja Riesberg, Janina Kalbertodt, Stefan Baumann & Nikolaus P. Himmelmann. 2018. On the perception of prosodic prominences and boundaries in Papuan Malay. In Sonja Riesberg, Asako Shiohara & Atsuko Utsumi (eds.), Perspectives on informa- tion structure in Austronesian languages, 389–414. Berlin: Language Science Press. DOI:10.5281/zenodo.1402559 S. Riesberg, J. Kalbertodt, S. Baumann & N. -

Prosodic Systems: Austronesian Nikolaus P

1 Prosodic systems: Austronesian Nikolaus P. Himmelmann (Universität zu Köln) & Daniel Kaufman (Queens College, CUNY & ELA) 30.1 Introduction Figure 1. The Austronesian family tree (Blust 1999, Ross 2008) Austronesian languages cover a vast area, reaching from Madagascar in the west to Hawai'i and Easter Island in the east. With close to 1300 languages, over 550 of which belong to the large Oceanic subgroup spanning the Pacific Ocean, they constitute one of the largest well- established phylogenetic units of languages. While a few Austronesian languages, in particular Malay in its many varieties and the major Philippine languages, have been documented for some centuries, most of them remain underdocumented and understudied. The major monographic reference work on Austronesian languages is Blust (2013). Adelaar & Himmelmann (2005) and Lynch, Crowley & Ross (2005) provide language sketches as well as typological and historical overviews for the non-Oceanic and Oceanic Austronesian languages, respectively. Major nodes in the phylogenetic structure of the Austronesian family are shown in Figure 1 (see Blust 2013: chapter 10 for a summary). Following Ross (2008), the italicized groupings in Figure 1 are not valid phylogenetic subgroups, but rather collections of subgroups whose relations have not yet been fully worked out. The groupings in boxes, on the other hand, are thought to represent single proto-languages and have been partially reconstructed using the comparative method. Most of languages mentioned in the chapter belong to the Western Malayo-Polynesian linkage, which includes all the languages of the Philippines and, with a few exceptions, Indonesia. When dealing with languages from other branches, this is explicity noted.