Poole Harbour: Current Understanding of the Later Prehistoric to Medieval Archaeology and Future Directions for Research

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Poole Harbour Status List

The Poole Harbour Status List Mute Swan – Status – Breeding resident and winter visitor. Good Sites – Seen sporadically around the harbour but Poole Park, Hatch Pond, Brands Bay, Little Sea, Ham Common, Arne, Middlebere, Swineham and Holes Bay are all good sites. Bewick’s Swan Status – Uncommon winter visitor. Once a regular winter visitor to the Frome Valley now only arrives in hard or severe winters. Good Sites – Along the Frome Valley leading to Wareham water meadows and Bestwall Whooper Swan Status – Rare winter visitor and passage migrant Good Sites – In the 60’s there were regular reports of birds over wintering on Little Sea, however, sightings are now mainly due to extreme weather conditions. Bestwall, Wareham Water Meadows and the harbour mouth are all potential sites Tundra Bean Goose Status – Vagrant to the harbour Taiga Bean Goose Status – Vagrant to the harbour Pink-footed Goose Status – Rare winter visitor. Good Sites – Middlebere and Wareham Water Meadows have the most records for this species White-fronted Goose Status – Once annual, but now scarce winter visitor. Good Sites – During periods of cold weather the best places to look are Bestwall, Arne, Keysworth and the Frome Valley. Greylag Goose Status – Resident feral breeder and rare winter visitor Good Sites – Poole Park has around 10-15 birds throughout the year. Swineham GP, Wareham Water Meadows and Bestwall all host birds during the year. Brett had 3 birds with collar rings some years ago. Maybe worth mentioning those. Canada Goose Status – Common reeding resident. Good Sites – Poole Park has a healthy feral population. Middlebere late summer can host up to 200 birds with other large gatherings at Arne, Brownsea Island, Swineham, Greenland’s Farm and Brands Bay. -

36/18 Corfe Castle Parish Council

CORFE CASTLE PARISH COUNCIL MINUTES OF THE ANNUAL GENERAL MEETING OF THE PARISH COUNCIL HELD AT THE TOWN HALL, CORFE CASTLE ON MONDAY 9th July 2018 - The meeting commenced at 7.00pm PRESENT: Cllr Steve Clarke (Acting Chairman), Cllr Morrison Wells, Cllr Haywood, Cllr Spicer-Short, Cllr Parish, Cllr Marshallsay, Cllr Spinney, Cllr Dragon. There was one member of the public present. PUBLIC HALF HOUR. No members of the Public spoke. Cllr Clarke opened the meeting by extending the Council’s condolences to Cllr Dru Drury following the death of Diana Dru Drury 1. APOLOGIES FOR ABSENCE: Cllr Dru Drury, Cllr Dando 2. DECLARATIONS OF INTEREST AND DISPENSATIONS: The Council adopted the Code of Conduct set out on the Communities and Local Government website at the 10th September 2012 Meeting (Page 155, para 3.7). Declarations of Interests received for all Councillors. All Councillors are granted a dispensation to set the Precept. Cllr Parish has submitted her declarations and dispensations to the Clerk and they have been sent to the monitoring officer. 3. TO CONFIRM THE MINUTES OF THE LAST MEETING: The draft minutes of the meeting held on the 11th of June 2018 were confirmed as a true record of proceedings and were signed. 4. COUNTY COUNCILLORS REPORT: Cllr Brooks was asked about the impact of Christchurch’s judicial review? She replied the Council are continuing with planning for LGR as they have no other option. Should the case be found in Christchurch’s favour LGR could collapse. Cllr Brooks reported the Shadow Council is now in place and the Shadow Exec’ is in place. -

Download Brochure

B WELCOME TO THE HEART OF THE DORSET COUNTRYSIDE INTRODUCING WAREHAM Nestled on the banks of the River Frome, Wareham is a beautiful town with its own deep history. Wareham is the perfect escape on a sunny summer’s day. You’ll be spoiled for choice when it comes to food and drink. Take a stroll along the many riverside paths, hire a boat Cakes and cream teas aplenty, honest pub grub, and elegant or cruise down the river in style on a paddle steamer. The fine dining can all be found just a stone’s throw from one town’s quay is also a lively social spot, host to many events another all using only the freshest local ingredients. If luxury and activities throughout the year, plus the weekly farmer’s is what you’re after, then why not treat yourself to dinner at market which is sure to attract a crowd. The Priory where delicious is always on the menu. Independent is the name of the game in Wareham. Vintage Or take the favoured window seat of author and adventurer boutiques, quirky antique shops and galleries stocking T.E. Lawrence, affectionately known as Lawrence of Arabia, the most beautiful pieces from talented local artists, all who used to meet close friend Thomas Hardy at The line the town’s central cross roads. The Creative Gallery is Anglebury for coffee. worth a browse; run as a co-operative you’ll find artists in residence hard at work and chatting to customers about We definitely recommend adding Wareham onto your their creations. -

The Frome 8, Piddle Catchmentmanagement Plan 88 Consultation Report

N 6 L A “ S o u t h THE FROME 8, PIDDLE CATCHMENTMANAGEMENT PLAN 88 CONSULTATION REPORT rsfe ENVIRONMENT AGENCY NATIONAL LIBRARY & INFORMATION SERVICE ANGLIAN REGION Kingfisher House. Goldhay Way. Orton Goldhay, Peterborough PE2 5ZR NRA National Rivers Authority South Western Region M arch 1995 NRA Copyright Waiver This report is intended to be used widely and may be quoted, copied or reproduced in any way, provided that the extracts are not quoted out of context and that due acknowledgement is given to the National Rivers Authority. Published March 1995 ENVIRONMENT AGENCY Hill IIII llll 038007 FROME & PIDDLE CATCHMENT MANAGEMENT PLAN CONSULTATION REPORT YOUR VIEWS The Frome & Piddle is the second Catchment Management Plan (CMP) produced by the South Wessex Area of the National Rivers Authority (NRA). CMPs will be produced for all catchments in England and Wales by 1998. Public consultation is an important part of preparing the CMP, and allows people who live in or use the catchment to have a say in the development of NRA plans and work programmes. This Consultation Report is our initial view of the issues facing the catchment. We would welcome your ideas on the future management of this catchment: • Hdve we identified all the issues ? • Have we identified all the options for solutions ? • Have you any comments on the issues and options listed ? • Do you have any other information or ideas which you would like to bring to our attention? This document includes relevant information about the catchment and lists the issues we have identified and which need to be addressed. -

Phase 1 Report, July 1999 Monitoring Heathland Fires in Dorset

MONITORING HEATHLAND FIRES IN DORSET: PHASE 1 Report to: Department of the Environment Transport and the Regions: Wildlife and Countryside Directorate July 1999 Dr. J.S. Kirby1 & D.A.S Tantram2 1Just Ecology 2Terra Anvil Cottage, School Lane, Scaldwell, Northampton. NN6 9LD email: [email protected] web: http://www.terra.dial.pipex.com Tel/Fax: +44 (0) 1604 882 673 Monitoring Heathland Fires in Dorset Metadata tag Data source title Monitoring Heathland Fires in Dorset: Phase 1 Description Research Project report Author(s) Kirby, J.S & Tantram, D.A.S Date of publication July 1999 Commissioning organisation Department of the Environment Transport and the Regions WACD Name Richard Chapman Address Room 9/22, Tollgate House, Houlton Street, Bristol, BS2 9DJ Phone 0117 987 8570 Fax 0117 987 8119 Email [email protected] URL http://www.detr.gov.uk Implementing organisation Terra Environmental Consultancy Contact Dominic Tantram Address Anvil Cottage, School Lane, Scaldwell, Northampton, NN6 9LD Phone 01604 882 673 Fax 01604 882 673 Email [email protected] URL http://www.terra.dial.pipex.com Purpose/objectives To establish a baseline data set and to analyse these data to help target future actions Status Final report Copyright No Yes Terra standard contract conditions/DETR Research Contract conditions. Some heathland GIS data joint DETR/ITE copyright. Some maps based on Ordnance Survey Meridian digital data. With the sanction of the controller of HM Stationery Office 1999. OS Licence No. GD 272671. Crown Copyright. Constraints on use Refer to commissioning agent Data format Report Are data available digitally: No Yes Platform on which held PC Digital file formats available Report in Adobe Acrobat PDF, Project GIS in MapInfo Professional 5.5 Indicative file size 2.3 MB Supply media 3.5" Disk CD ROM DETR WACD - 2 - Phase 1 report, July 1999 Monitoring Heathland Fires in Dorset EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Lowland heathland is a rare and threatened habitat and one for which we have international responsibility. -

Draft Christchurch and Waterw

1 Contents Page Acronyms 4 Foreword 5 Executive Summary 6 Structure of the Document 6 Section 1 Chapter 1 – The Plan 7 1.1 Introduction 7 1.2 Background to the Management Plan 7 Chapter 2 -The Plan’s Aims and Objectives 9 2.1 Strategic Aims 9 2.2 Management Plan Objectives 9 Chapter 3 - Management Area and Statutory Framework 10 3.1 Geographical Area 10 3.2 Ownership and Management Planning 12 3.3 Statutory Context 15 3.4 Planning and Development Control 16 3.5 Public Safety and Enforcement 17 3.6 Emergency Planning 17 Chapter 4 – Ecology and Archaeology 19 4.1 Introduction 19 4.2 Ecological Features 19 4.3 Physical Features 23 4.4 Archaeology 24 Chapter 5 - Recreation and Tourism 26 5.1 Introduction 26 5.2 Economic Value 26 5.3 Events 27 5.4 Access 27 5.5 Boating 27 5.6 Dredging 30 5.7 Signage, Lighting and Interpretation 31 Chapter 6 – Fisheries 32 6.1 Angling 32 6.2 Commercial Fishing 32 Chapter 7 - Education and Training 36 7.1 Introduction 36 7.2 Current use 37 Chapter 8 - Water Quality and Pollution 37 8.1 Introduction 37 8.2 Eutrophication and Pollution 37 8.3 Bathing Water Quality 37 Chapter 9 - Managing the Shoreline 39 9.1 Introduction 39 9.2 Climate Change and Sea Level Rise 40 9.3 Flood and Coastal Erosion Risk Management 40 9.4 Shoreline Management Plans (SMPs) 41 2 Chapter 10 – Governance of the Management Plan 43 10.1 Introduction 43 10.2 Future Governance Structure and Framework - Proposals 43 10.3 Public Consultation 43 10.4 Funding 43 10.5 Health and Safety 44 10.6 Review of the Christchurch Harbour and Waterways Plan -

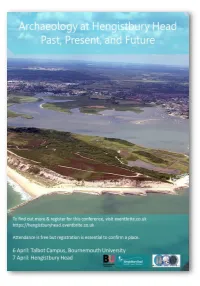

Hengistbury-Head-Event-Leaflet.Pdf

Programme Saturday 6 April 9:30 – 17:00 Bournemouth University (Kimmeridge House, Talbot Campus, BH12 5BB) 09:30 – 09:45 Welcome and Introduction Professor Tim Darvill (Bournemouth University) 09:45 – 10:15 Geology and Ecology of Hengistbury Head Peter Hawes 10:15 – 11:00 Ice Age landscapes and hunters at Hengistbury Head Professor Nick Barton. (University of Oxford) 11:00 – 11:30 Refreshments and displays 11:30 – 12:15 Early Neolithic Hengistbury and the lower Avon valley Dr Kath Walker (Bournemouth Borough Council & Bournemouth University) 12:15 – 12:45 Later Neolithic Hengistbury Head and its context Dr Julie Gardiner 12:45 – 13:00 Geophysical surveys at Hengistbury Head Dr Eileen Wilkes (Bournemouth University) 13:00 – 14:00 Lunch 14:00 – 14:45 A gateway to the Continent: the Early Bronze Age cemetery at Hengistbury Head Dr Clément Nicholas 14:45 – 15:30 Iron Age and Roman communities at Hengistbury Head Professor Sir Barry Cunliffe (University of Oxford) 15:30 – 16:00 Refreshments and displays 16:00 – 16:45 Post-Roman Hengistbury Head and the vision for the Visitor Centre Mark Holloway (Bournemouth Borough Council) 16:45 – 17:00 Discussion 17:00 – 18:00 Wine reception and networking Sunday 7 April 9:30 – 15:00 Hengistbury Head Visitor Centre (Bournemouth, Dorset, BH6 4EN) 09:30 – 12:30 A walk on the Head Led by Mark Holloway, Gabrielle, Delbarre, and Dr Kath Walker 12:30 – 13:30 Lunch 13:30 – 15:00 Formulating an archaeological research agenda for Hengistbury Head 2020-2025 A workshop facilitated by Professor Tim Darvill and Dr Kath Walker Sandwiched between Christchurch Harbour and the English Channel, Hengistbury Head has been the scene of settlement and ceremony for more than twelve thousand years. -

Introducing Ahoy! WELCOME to the First Edition of the Newsletter for the Friends of Hengistbury Head Lookout and Watchkeepers Alike

Ahoy! National Coastwatch Institution www.nci.org.uk Issue 1 December 2019 Introducing Ahoy! WELCOME to the first edition of the newsletter for the Friends of Hengistbury Head Lookout and Watchkeepers alike. The word “ahoy” has several derivations but is most familiar to us as a general maritime call to attract someone’s attention, perhaps to alert them to something of interest ….. what better name for our bi-monthly publication, designed to keep you informed of all the recent and forthcoming activities of NCI Hengistbury Head? We are most grateful to all our Friends for your ongoing support and would be interested to receive any feedback regarding this newsletter. Please address any comments to our Friends administrator Maureen Taylor [email protected] who will forward them to the editing team. Thank you! In this issue: In Focus – a regular feature about our volunteers. This issue – Peter Holway, Acting Station Manager NCI around the coast – an occasional series as Friends and Watchkeepers visit other Stations With thanks – fundraising update Been there, done that – a summary of recent Station events Congratulations – recently qualified Watchkeepers Looking forward – planned events Stay in touch – essential contact details In Focus Name Peter Holway Role within Station Acting Station Manager * Tell us a little about the role at present Our current aim is to achieve DFS (Declared Facility Status) in the near future and I am, therefore, bringing all my communication, negotiation and team building skills into play to ensure the smooth running of our Station in the run up to our DFS assessment. What is DFS and why is it important? Achieving DFS means that we will be officially recognised as part of the Maritime Search and Rescue (SAR) emergency services. -

Minutes of a Meeting of Church Knowle Parish Council Held at Furzebrook Village Hall on Tuesday 14Th May 2016

Minutes of a meeting of Church Knowle Parish Council held at Furzebrook Village Hall on Tuesday 14th May 2016 PRESENT Council Members: C. K Parishioners & Members of the public: Cllr Mrs Kathryn Best Viop Unlimited – Managing Director Cllr Mr Colin Page Viop Unlimited – Technical Manager Cllr Mrs Hazel Parker - Vice-chairman Cllr Mr Leslie Bugler PDC Cllr Mr Malcolm Barnes (from 9.35pm – after Cllr Mr Ian Hollard discussion of Asset of Community Value(Min. 231) Cllr Mrs Billa Edwards Apologies: Cllr. Mr Derek Burt Cllr. Mr Tony Higgens Cllr. Mrs Jayne Wilson STATEMENT FROM CLERK 191.16 The Clerk advised the meeting that there being no elected Parish Council Chairman or Vice-chairman it would be necessary for Members present to elect a Chairman for the Meeting before the continuation of the meeting. ELECTION OF CHAIRMAN OF THE MEETING 192.16 Cllr Page proposed that past Vice-chairman Cllr Parker be Chairman for the Meeting. The proposal was seconded by Cllr Edwards. 193.16 Cllr Parker had no objection to the nomination and advised Members she would be willing to act as Chairman of the Meeting. 194.16 The Clerk asked Members if there were any other nominations. There were none. 195.16 Members voted unanimously in agreement of the motion (see Minute 192.16) that Cllr Parker be Chairman and she was duly appointed to the position for the June meeting of the Parish Council. 196.16 Cllr Parker took the Chair of the Meeting. APOLOGIES 197.6 The Clerk advised the Meeting he had received apologies for absence from Cllrs Derek Burt, Jane Wilson and Tony Higgens and an apology for possible late arrival from Purbeck DC Cllr Malcolm Barnes. -

Estuary Assessment

Appendix I Estuary Assessment Poole and Christchurch Bays SMP2 9T2052/R1301164/Exet Report V3 2010 Haskoning UK Ltd on behalf of Bournemouth Borough Council Poole & Christchurch Bays SMP2 Sub-Cell 5f: Estuary Processes Assessment Date: March 2009 Project Ref: R/3819/01 Report No: R.1502 Poole & Christchurch Bays SMP2 Sub-Cell 5f: Estuary Processes Assessment Poole & Christchurch Bays SMP2 Sub-Cell 5f: Estuary Processes Assessment Contents Page 1. Introduction....................................................................................................................1 1.1 Report Structure...........................................................................................................1 1.2 Literature Sources........................................................................................................1 1.3 Extent and Scope.........................................................................................................2 2. Christchurch Harbour ....................................................................................................2 2.1 Overview ......................................................................................................................2 2.2 Geology........................................................................................................................4 2.3 Holocene to Recent Evolution......................................................................................4 2.4 Present Geomorphology ..............................................................................................5 -

Report on the Investigation of the Brenscombe Outdoor Centre Canoe Swamping Accident in Poole Harbour, Dorset on 6 April 2005 Ma

Report on the investigation of the Brenscombe Outdoor Centre canoe swamping accident in Poole Harbour, Dorset on 6 April 2005 Marine Accident Investigation Branch Carlton House Carlton Place Southampton United Kingdom SO15 2DZ Report No 22/2005 December 2005 Extract from The United Kingdom Merchant Shipping (Accident Reporting and Investigation) Regulations 2005 – Regulation 5: “The sole objective of the investigation of an accident under the Merchant Shipping (Accident Reporting and Investigation) Regulations 2005 shall be the prevention of future accidents through the ascertainment of its causes and circumstances. It shall not be the purpose of an investigation to determine liability nor, except so far as is necessary to achieve its objective, to apportion blame.” NOTE This report is not written with litigation in mind and, pursuant to Regulation 13(9) of the Merchant Shipping (Accident Reporting and Investigation) Regulations 2005, shall be inadmissible in any judicial proceedings whose purpose, or one of whose purpose is to attribute or apportion liability or blame. CONTENTS Page GLOSSARY OF ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS SYNOPSIS 1 SECTION 1 - FACTUAL INFORMATION 3 1.1 Particulars of canoe swamping accident 3 1.2 Brenscombe Outdoor Centre 5 1.3 Leadership Direct, client and course 5 1.4 Accident background 6 1.4.1 Exercise aim 6 1.4.2 Exercise area 6 1.5 Narrative 9 1.5.1 Pre-water preparations 10 1.5.2 Transit 10 1.5.3 Rescue 13 1.5.4 Client’s reaction 16 1.6 BOC staff 16 1.6.1 Staff 16 1.6.2 Safety instructor 16 1.6.3 Additional instructor -

Canoeing in Poole Harbour

wildlife in Poole Harbour Poole in wildlife and safety sea to guide Your Poole Harbour is home to a wealth Avocet of wildlife as well as being a busy Key Features: Elegant white and black wader with distinctive upturned bill and long legs. commercial port and centre for a wide Best to spot: August to April Where: On a low tide Avocet flocks can be range of recreational activities. It is a found in several favoured feeding spots with fantastic sheltered place to explore the southern tip of Round Island and the mouth of Wytch Lake being good places. However these are sensitive feeding by canoe all year round, although zones and it’s not advised to kayak here on a low or falling tide. Always carry a means of calling for help and keep it Fact: Depending on the winter conditions, Poole Harbour hosts the it’s important to remember this within reach (waterproof VHF radio, mobile phone, 2nd or 3rd largest overwintering flock of Avocet in the country. whistles and flares). site is important for birds (Special Protection Area). Wear a personal flotation device. Get some training: contact British Canoeing Red Breasted Merganser Harbour www.britishcanoeing.org.uk or the Poole Harbour Key Features: Both males and females have a Canoe Club www.phcc.org.uk for local information. spiky haircut on the back of their heads and males have a distinct green glossy head and Poole in in Wear clothing appropriate for your trip and the weather. red eye. Best to spot: October to March Always paddle with others.