Why Investigative Journalism Matters

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Peace Envoy Moves Stir New End-War Speculation WASHINGTON (AP) - Some Diplomats Here and in an Uneasy Thieu That Presi- Paris Monday, Will Confer the Paris Talks

Police Probe Triple SEE STORY PACE 2 The Weather ,v Sunny and pleasant today,' THEDAILY FINAL clear and cool tonight Tomor- row fair and a little warmer. Red Bank, Freehold Long Branch EDITION 30 PACES Monniouth County's Outstanding Home Newspaper VOL. 95 NO. 37 RED BANK, NJ. WEDNESDAY. AIJGUST 16.1972 TEN CENTS iiiiiiiuiiNiiniiiiiiii Cahill Plans Low-Key Role In Republican Convention By JAMES U.RUBIN the up-coming gathering of ture soundly defeated his tax culties may be a liability. expect this," said Cahill, who the GOP ranks in Miami reform program. "The President will be twice has attended con- TRENTON (AP) - Gov. Beach. Cahill is the chairman of the judged on what he has done in ventions as'an observer. William T. Cahill, anticipating When plans for the con- Nixon-Agnew campaign in the last four years as Bill "They recognize there is no an uneventful Republican Na- vention were made at the re- New Jersey, a key north- Cahill will be judged on his contest. It's a recognition that tional Convention, says be will cent National Governors Con- eastern state and the eighth record;" the governor said. the overwhelming number of play a subdued, low-key role ference, Cahill said, "1 knew largest in the nation. Furthermore, he remarked, Republicans are satisfied with in Miami Beach next week. at the time the President However, he is leaving the "The people in this state know the administration." Cahill, the chairman of New would be toe candidate and day-to-day chores of manag- Bill Cahill for what he is. -

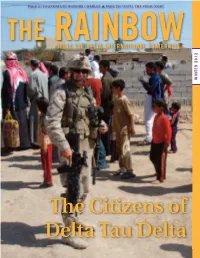

2012 Winter Vol 136 No 1

PAGE 8 | FOUNDATION HONORS CHARLES p PAGE 38 | UNTIL THE FINAL SNAP THE RAINBOW DELTA TAU DELTA INTERNATIONAL FRATERNITY WINTER 2012 The Citizens of Delta Tau Delta In partnership with 36 other fraternities and sororities committed to ending bullying and hazing on college campuses CONTENTS THE RAINBOW | VOLUME 136, NO. 1 | WINTER 2012 28 Cover Story Think Green We the Citizens, of Delta Tau Delta 5 Fraternity Headlines Insert topics he Expansions for Fall 2012 Delaware and UCSB Receive Charters Quinnipiac Brothers Grow ‘Staches for Cash PERIODICAL STATEMENT The Rainbow (ISSN 1532-5334) is published twice annually for $10 per year by Delta Tau Delta Fraternity at 10000 Allisonville Road, 10 A Lifetime of Service Fishers, Indiana 46038-2008; Telephone 1-800- MAGAZINE MISSION DELTSXL; http://www.delts.org. Periodical Insert topics Ken File Reflects on His Time Serving Delta Tau Delta p Inform members of the events, postage paid at Fishers, Indiana and at activities and concerns of inter- additional mailing offices. POSTMASTER: Send re address changes to Delta Tau Delta Fraternity, est to members of the Fraternity. 10000 Allisonville Road, Fishers, Indiana 12 Annual Report p Attract and involve members of 46038-2008. Canada Pub Agree #40830557. the Fraternity via appropriate Canada return to: Station A, P.O. Box 54, coverage, information and opin- Windsor, ON N9A 6J5 [email protected] ion stories. STATEMENT OF OWNERSHIP p Educate present and potential 1. Publication Title –THE RAINBOW; 14 Alumni in the News members on pertinent issues, 2. Publication No.–1532-5334; 3. Filing Date– Sept. 25, 2008; 4. Issue Frequency–Biannual; Insert topi persons, events and ideas so 5. -

Fostering Healthy Neighborhoods

Fostering Healthy Neighborhoods RESEARCH BRIEF Alignment across the community development, health and financial well-being sectors. A PROJECT AND REPORT LED BY Build Healthy Places Network Prosperity Now Financial Health Network Table of Contents 3 Overview 7 Key Findings 13 Conclusion 14 Appendix A – Examples of Existing Work 18 Appendix B – Public Health and Healthcare Sectors Overview 24 Appendix C – Community Development Sector Overview 27 Appendix D – Financial Well-being Sector Overview 30 Appendix E – Interviews 30 Appendix F – Focus Groups 32 Appendix G – List of Resources Support for this report was provided by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. The views expressed here do not necessarily reflect the views of the Foundation. Research and writing contributor Paul DeManche 2 FOSTERING HEALTHY NEIGHBORHOODS | 3 Overview Substantial evidence links financial well-being and health. As income and wealth increase or decrease, so does health. Individuals and families with more wealth and higher incomes are better able to access the material and physical conditions that facilitate good health and are less likely to suffer from the mental and physical effects of financial stress caused by income volatility, insufficient savings, and unmanageable debt. The physical, social, and economic conditions FIGURE 1. FRAMEWORK FOR in our neighborhoods have a significant impact NEIGHBORHOODS THAT SUPPORT on both our health and financial well-being HEALTH AND FINANCIAL because they shape the opportunities we have WELLBEING and the choices that are available -

HSCA Volume V: 9/28/78

378 Obviously, the possibility cannot be dismissed, although it can hardly be said to have been established. At this point, it is, in your words, Mr. Chairman, perhaps only a little more than a "suspicion suspected," not a "fact found." The committee decided early in its investigation, as soon as it realized that a Mafia plot to assassinate the President warranted serious consideration, to assemble the most reliable information available on organized crime in the United States. The details of this phase of the committee's investigation will, of course, appear, hopefully in full, in its final report, a report that will consider the background of organized crime in America, the structure o£ the Mafia in the early 1960's, the effort by the Kennedy administration to suppress the mob, and the evidence that the assassination might have been undertaken in retaliation for those efforts. To scrutinize the possible role of organized crime in the assassi- nation, the committee early brought on one of the country's lead- ing experts on the subject. He is Ralph Salerno, whose career as an organized crime investigator with the New York City Police De- partment goes back to 1946. Mr. Salerno has since retired from the New York City Police Department and I would note that on the day of his retirement, the New York Times was moved to comment that he perhaps knew more about the Mafia than any nonmember in the United States. It would be appropriate at this time, Mr. Chairman, to call Ralph Salerno. Chairman STOKES . The committee calls Mr. -

The Testimony of William Bulger Hearin

THE NEXT STEP IN THE INVESTIGATION OF THE USE OF INFORMANTS BY THE DEPARTMENT OF JUSTICE: THE TESTIMONY OF WILLIAM BULGER HEARING BEFORE THE COMMITTEE ON GOVERNMENT REFORM HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES ONE HUNDRED EIGHTH CONGRESS FIRST SESSION JUNE 19, 2003 Serial No. 108–41 Printed for the use of the Committee on Government Reform ( Available via the World Wide Web: http://www.gpo.gov/congress/house http://www.house.gov/reform U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 89–004 PDF WASHINGTON : 2003 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Internet: bookstore.gpo.gov Phone: toll free (866) 512–1800; DC area (202) 512–1800 Fax: (202) 512–2250 Mail: Stop SSOP, Washington, DC 20402–0001 VerDate 11-MAY-2000 09:36 Oct 02, 2003 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 5011 Sfmt 5011 D:\DOCS\89004 HGOVREF1 PsN: HGOVREF1 COMMITTEE ON GOVERNMENT REFORM TOM DAVIS, Virginia, Chairman DAN BURTON, Indiana HENRY A. WAXMAN, California CHRISTOPHER SHAYS, Connecticut TOM LANTOS, California ILEANA ROS-LEHTINEN, Florida MAJOR R. OWENS, New York JOHN M. MCHUGH, New York EDOLPHUS TOWNS, New York JOHN L. MICA, Florida PAUL E. KANJORSKI, Pennsylvania MARK E. SOUDER, Indiana CAROLYN B. MALONEY, New York STEVEN C. LATOURETTE, Ohio ELIJAH E. CUMMINGS, Maryland DOUG OSE, California DENNIS J. KUCINICH, Ohio RON LEWIS, Kentucky DANNY K. DAVIS, Illinois JO ANN DAVIS, Virginia JOHN F. TIERNEY, Massachusetts TODD RUSSELL PLATTS, Pennsylvania WM. LACY CLAY, Missouri CHRIS CANNON, Utah DIANE E. WATSON, California ADAM H. PUTNAM, Florida STEPHEN F. LYNCH, Massachusetts EDWARD L. SCHROCK, Virginia CHRIS VAN HOLLEN, Maryland JOHN J. -

Conflict of Interest, Ethics Among Tops

In this issue: car care supplement I m t r n a l M e m b e r M e m b e r MATAWAN , NEW JERSEY, Thursday, May 25, 1972 Single Copy Fifteen Cants' 103rd YEAR M |h WEEK National Newspaper Association N e w Je r s e y Press Association BEADLESTON SPEAKER Conflict of interest, ethics among tops MATAWAN - Sen. Alfred “ accomplishments’' in the would be state-operated and Also mentioned were the package, saying passage N. Beadlcston, Republican legislature during this year, away from the local tracks so making the New Jersey would ‘‘take money out of the majority leader spoke discussed what would be as to not hurt their business Parole Board a full-time right hand pockct and put less yesterday at the Matawan debated at the "improperly as had been done in New York board of three men instead of into the left hand pocket” . Chamber of Commerce termed special session" in off-track betting; ratification a five man parttime board in Included in the package is a election luncheon at Don June, the lax reform addition to bills lo help personal income tax and a Quixote Inn where he package, and answered some rehabilitate parolees; a statewide real estate tax. discussed some of the major <|uestions from the floor. constitutional amendment Sen. Beadleston said the KICK-OFF DINNER-The Hasilian Father of Mariapocli, Malawan, held a building fund legislation in the senate this Listed were adoption of a making 1 state attorney measures would “ put a kick-off dinner Saturday night at the Magnolia Inn attended by more than ISO people. -

Saving Seabiscuit: an Argument for the Establishment of a Federal Equine Sports Commission

Volume 28 Issue 1 Article 4 2-3-2021 Saving Seabiscuit: An Argument for the Establishment of A Federal Equine Sports Commission Celso Lucas Leite,Jr. Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.law.villanova.edu/mslj Part of the Animal Law Commons, Entertainment, Arts, and Sports Law Commons, Gaming Law Commons, Legislation Commons, and the State and Local Government Law Commons Recommended Citation Celso L. Leite,Jr., Saving Seabiscuit: An Argument for the Establishment of A Federal Equine Sports Commission, 28 Jeffrey S. Moorad Sports L.J. 135 (2021). Available at: https://digitalcommons.law.villanova.edu/mslj/vol28/iss1/4 This Comment is brought to you for free and open access by Villanova University Charles Widger School of Law Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Jeffrey S. Moorad Sports Law Journal by an authorized editor of Villanova University Charles Widger School of Law Digital Repository. \\jciprod01\productn\V\VLS\28-1\VLS104.txt unknown Seq: 1 25-JAN-21 12:07 Leite,Jr.: Saving Seabiscuit: An Argument for the Establishment of A Federal SAVING SEABISCUIT: AN ARGUMENT FOR THE ESTABLISHMENT OF A FEDERAL EQUINE SPORTS COMMISSION I. DEATH ON THE TRACK In January 2020, three horses died in three days at the Santa Anita racetrack in Arcadia, California.1 Racing officials euthanized the horses following the accidents at the track, prompting fierce criticism from animal rights groups.2 These incidents added to a death toll of five horses in January 2020 and followed a cascade of fifty-six deaths -

AUGUST 2007 • Page 1 Nahant Harbor Review

NAHANT HARBOR REVIEW • AUGUST 2007 • Page 1 Nahant Harbor Review A monthly publication, in service since March 1994, dedicated to strengthening the spirit of community by serving the interests of civic, religious and business organizations of Nahant, Massachusetts, USA. Volume 14 Issue 8 AUGUST 2007 Nahanter Rachel Tarmy Celebrate 25 Years with My Brother’s Competes for Miss Teen Boston Table at Summer Garden Party Aug. 9th Rachel Tarmy of Nahant, daughter of Les and Julie Tarmy, was recently selected, to participate in The Summer Garden Party, a critical fund-raiser to benefit the North Shore’s largest Nationals’ 2007 Miss Teen Boston pageant competi- soup kitchen, My Brother’s Table, in Lynn, will take place on August 9th, at Marian tion, that will take place on July 29th, 2007. Rachel Court College, Little’s Point Road, in learned of her acceptance into this year’s competition, Swampscott, beginning at 7:00 p.m. as Nationals, Inc. Tickets start at $65. This vital event announced their includes the auction of an Italian Villa selections on Vacation, from the Parker Company, as Monday, July 2nd. well as a catered event for 50, from Rachel submitted Tiger Lily Caterers of Beverly. Please an application and RSVP Mary at 781-595-3224. took part in an This year, My Brother’s Table is interview session, celebrating 25 years of operation; it has that was con- served over two million meals to the ducted by Patty hungry, since 1982. Last year, over Niedert, this year’s 80,000 meals were served to those in Boston Pageant need. -

BCRP Brochure 2021 Class

Boston Combined Residency Program This brochure describes the residency program as we assume it will -19 exist will in be JulyThe 2021, Pediatric by which time Residency authorities Training Program predict a vaccine to COVID of available. If thatBoston is not the Children’s case and the Hospital pandemic is still active, the program Harvard Medical School will be very similar but many of the and educational conferences and other group activities Bostonwill be virtual Medical instead Center Boston University School of Medicine of in-person, as they are today. August 2020 edi,on CLASS OF 2021.. BOSTON COMBINED RESIDENCY PROGRAM Boston Medical Center Boston Children’s Hospital CONTENTS History…………........................... 3 Rotation # descriptions.................. 47# Global health fellowships............ 84# BCRP…........................................ 3# Night call................................... 53# Global health grants………….… 84 # Boston Children’s Hospital........... 3# Longitudinal ambulatory.............. 54# Diversity and Inclusion................. 84# Boston Medical Center................. 8# Electives………………………….. 55# Salaries and benefits.................... 87# People……................................... 11 Individualized curriculum............ 56# Child care................................... 88# Program director biosketches...... 11# Academic development block.. 56# O$ce of fellowship training....... 88# Residency program leadership..... 12# Education.................................... 57# Cost of living.............................. -

Public Annex

UNITED IT-04-75-AR73.1 378 A378 - A23 NATIONS 02 December 2015 SF International Tribunal for the Case No. IT-04-75-AR73.1 Prosecution of Persons Responsible for Serious Violations of Date: 2 December 2015 International Humanitarian Law Committed in the Territory of the former Yugoslavia since 1991 IN THE APPEALS CHAMBER Before: A Bench of the Appeals Chamber Registrar: Mr. John Hocking Date: 2 December 2015 THE PROSECUTOR v. GORAN HADŽIĆ PUBLIC ANNEX BOOK OF AUTHORITIES FOR PROSECUTION’S URGENT INTERLOCUTORY APPEAL FROM CONSOLIDATED DECISION ON THE CONTINUATION OF PROCEEDINGS The Office of the Prosecutor: Mr. Douglas Stringer Counsel for Goran Had`i}: Mr. Zoran Živanović Mr. Christopher Gosnell IT-04-75-AR73.1 377 BOOK OF AUTHORITIES FOR PROSECUTION’S URGENT INTERLOCUTORY APPEAL FROM CONSOLIDATED DECISION ON THE CONTINUATION OF PROCEEDINGS Table of Contents: 1. CASE LAW OVERVIEW: .............................................................................3 2. CASE LAW CATEGORISED BY COUNTRY / COURT: A. AUSTRALIA .........................................................................................................6 B. CANADA ...........................................................................................................60 C. ECtHR ...........................................................................................................128 D. ECCC ............................................................................................................148 E. ICC.................................................................................................................182 -

Celebrating 25 Years of Trooper Camaraderie

Volume 23, Issue 1 Winter 2014 Celebrating 25 years of trooper camaraderie AAST serves, connects troopers for quarter century Twenty-five years ago, a small group Today AAST can do more than merely mail of Florida state troopers had the vision letters to its members to notify them of needs to create an association that would unite in the trooper family. state troopers across the country and When AAST learns that a trooper has an assist them by providing valuable benefits extreme need – a job-related injury, a long- and services. term illness, loss from a natural disaster, Thus was born the American Association an ill child – AAST has the capability of of State Troopers. e-mailing its members with the quick click Thousands of state troopers have been of a button and calling them to action. Tens first-hand recipients of AAST benefits: of thousands of dollars have been sent in scholarships for their children, insurance, from concerned troopers to help their fel- donations from AAST’s Brotherhood Assis- low troopers in need. The thin blue line tance Fund, and donations sent from their knows no state boundaries. fellow state troopers around the country. In November 2010, 2-year-old Wyatt Bai- ley, son of Tpr. Jason It is humbling, to say the least, to be Bailey of the Idaho State Police was diagnosed a recipient of such an outpouring with lymphoid nodular hyperplasia, a serious of support and brotherhood. digestive disorder. Not Tpr. John Ollquist, after Hurricane Sandy struck his home only did AAST send a Brotherhood Assistance AAST’s most highly touted benefit donation, but troopers around the country since its inception in 1989 has been its sent a staggering $12,647 to help little Wyatt. -

A Presente Edição Segue a Grafia Do Novo Acordo Ortográfico Da Língua Portuguesa

A presente edição segue a grafia do novo Acordo Ortográfico da Língua Portuguesa. [email protected] www.marcador.pt facebook.com/marcadoreditora © 2015, Direitos reservados para Marcador Editora uma empresa Editorial Presença Estrada das Palmeiras, 59 Queluz de Baixo 2730-132 Barcarena © 2000 Dick Lehr e Gerard O’Neill Publicado originalmente nos Estados Unidos da América por PublicAffairs™, uma chancela de Perseus Books Group, 2000. Todos os direitos reservados. Nenhuma parte deste livro pode ser utilizada ou reproduzida em qualquer forma sem permissão por escrito. Título original: Black Mass Título: Jogo Sujo Autores: Dick Lehr e Gerard O’Neill Tradução: Francisco Silva Pereira Revisão: Silvina de Sousa Paginação: Maria João Gomes Imagens no interior: Cedidas pela Perseus Books LCC. Direitos Reservados. Arranjo de capa: Marina Costa / Marcador Editora Impressão e acabamento: Multitipo — Artes Gráficas, Lda. ISBN: 978-989-754-181-0 Depósito legal: 397 183/15 1.ª edição: setembro de 2015 ÍNDICE Elenco ................................................................................................. 11 Prólogo ................................................................................................ 15 Introdução .......................................................................................... 17 Introdução à edição de bolso .......................................................... 23 Mapa: O mundo de Whitey ............................................................. 25 PRIMEIRA PARTE um 1975 ....................................................................................................