Unicode from a Linguistic Point of View

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Typographic Contribution to Language

Chapter 1: Typography and language: a selective literature review In this chapter I shall review some of the typographic literature to give an impression of the ‘story so far’. The review is necessarily selective, and leaves out a great deal of valid and useful information about particular typographic problems. The purpose is not to list all that is known, but rather to sketch a background to the theoretical problems addressed in this study. By ‘typographic literature’ I mean writings that have explicitly set out to discuss some aspect of typography, rather than writings on other topics that might conceivably be relevant to typography (although I introduce quite a number of these in later chapters). It is appropriate to start by looking at what typographers themselves have written, before considering the approaches taken by those psychologists and linguists who have addressed typographic issues. Typographers on typography British typography is still heavily influenced by ‘the great and the good’ book typographers of the Anglo-American pre-war tradition, (for example Rogers 1943, Morison 1951, and Updike 1937). While they contributed a great deal of intelligent and scholarly writing on typography, it was mostly of a historical or technical rather than a theoretical character. Above all, they were concerned with the revival and creation of beautiful and effective letterforms, and with the design of readable prose, mainly for books but also newspapers. We should remember that the concept of ‘typo- graphy’ as an abstract entity was relatively new, as was the profession of ‘typographer’. Chapter 1 • 11 On the written evidence, it seems that they did not view typography as part of language so much as a channel for its transmission. -

New York Statewide Data Warehouse Guidelines for Extracts for Use In

New York State Student Information Repository System (SIRS) Manual Reporting Data for the 2015–16 School Year October 16, 2015 Version 11.5 The University of the State of New York THE STATE EDUCATION DEPARTMENT Information and Reporting Services Albany, New York 12234 Student Information Repository System Manual Version 11.5 Revision History Version Date Revisions Changes from 2014–15 to 2015–16 are highlighted in yellow. Changes since last version highlighted in blue. Initial Release. New eScholar template – Staff Attendance. CONTACT and STUDENT CONTACT FACTS fields for local use only. See templates at http://www.p12.nysed.gov/irs/vendors/2015- 16/techInfo.html. New Assessment Measure Standard, Career Path, Course, Staff Attendance, Tenure Area, and CIP Codes. New Reason for Ending Program Service code for students with disabilities: 672 – Received CDOS at End of School Year. Reason for Beginning Enrollment Code 5544 guidance revised. Reason for Ending Enrollment Codes 085 and 629 clarified and 816 modified. 11.0 October 1, 2015 Score ranges for Common Core Regents added in Standard Achieved Code section. NYSITELL has five performance levels and new standard achieved codes. Transgender student reporting guidance added. FRPL guidance revised. GED now referred to as High School Equivalency (HSE) diploma, language revised, but codes descriptions that contain “GED” have not changed. Limited English Proficient (LEP) students now referred to as English Language Learners (ELL), but code descriptions that contain “Limited English Proficient” or “LEP” have not changed. 11.1 October 8, 2015 Preschool/PreK/UPK guidance updated. 11.2 October 9, 2015 Tenure Are Code SMS added. -

Assessment of Options for Handling Full Unicode Character Encodings in MARC21 a Study for the Library of Congress

1 Assessment of Options for Handling Full Unicode Character Encodings in MARC21 A Study for the Library of Congress Part 1: New Scripts Jack Cain Senior Consultant Trylus Computing, Toronto 1 Purpose This assessment intends to study the issues and make recommendations on the possible expansion of the character set repertoire for bibliographic records in MARC21 format. 1.1 “Encoding Scheme” vs. “Repertoire” An encoding scheme contains codes by which characters are represented in computer memory. These codes are organized according to a certain methodology called an encoding scheme. The list of all characters so encoded is referred to as the “repertoire” of characters in the given encoding schemes. For example, ASCII is one encoding scheme, perhaps the one best known to the average non-technical person in North America. “A”, “B”, & “C” are three characters in the repertoire of this encoding scheme. These three characters are assigned encodings 41, 42 & 43 in ASCII (expressed here in hexadecimal). 1.2 MARC8 "MARC8" is the term commonly used to refer both to the encoding scheme and its repertoire as used in MARC records up to 1998. The ‘8’ refers to the fact that, unlike Unicode which is a multi-byte per character code set, the MARC8 encoding scheme is principally made up of multiple one byte tables in which each character is encoded using a single 8 bit byte. (It also includes the EACC set which actually uses fixed length 3 bytes per character.) (For details on MARC8 and its specifications see: http://www.loc.gov/marc/.) MARC8 was introduced around 1968 and was initially limited to essentially Latin script only. -

Synesthetes: a Handbook

Synesthetes: a handbook by Sean A. Day i © 2016 Sean A. Day All pictures and diagrams used in this publication are either in public domain or are the property of Sean A. Day ii Dedications To the following: Susanne Michaela Wiesner Midori Ming-Mei Cameo Myrdene Anderson and subscribers to the Synesthesia List, past and present iii Table of Contents Chapter 1: Introduction – What is synesthesia? ................................................... 1 Definition......................................................................................................... 1 The Synesthesia ListSM .................................................................................... 3 What causes synesthesia? ................................................................................ 4 What are the characteristics of synesthesia? .................................................... 6 On synesthesia being “abnormal” and ineffable ............................................ 11 Chapter 2: What is the full range of possibilities of types of synesthesia? ........ 13 How many different types of synesthesia are there? ..................................... 13 Can synesthesia be two-way? ........................................................................ 22 What is the ratio of synesthetes to non-synesthetes? ..................................... 22 What is the age of onset for congenital synesthesia? ..................................... 23 Chapter 3: From graphemes ............................................................................... 25 -

The Braille Font

This is le brailletex incl boxdeftex introtex listingtex tablestex and exampletex ai The Br E font LL The Braille six dots typ esetting characters for blind p ersons c comp osed by Udo Heyl Germany in January Error Reports in case of UNCHANGED versions to Udo Heyl Stregdaer Allee Eisenach Federal Republic of Germany or DANTE Deutschsprachige Anwendervereinigung T X eV Postfach E Heidelb erg Federal Republic of Germany email dantedantede Intro duction Reference The software is founded on World Brail le Usage by Sir Clutha Mackenzie New Zealand Revised Edition Published by the United Nations Educational Scientic and Cultural Organization Place de Fontenoy Paris FRANCE and the National Library Service for the Blind and Physically Handicapp ed Library of Congress Washington DC USA ai What is Br E LL It is a fontwhich can b e read with the sense of touch and written via Braille slate or a mechanical Braille writer by blinds and extremly eyesight disabled The rst blind fontanight writing co de was an eight dot system invented by Charles Barbier for the Frencharmy The blind Louis Braille created a six dot system This system is used in the whole world nowadays In the Braille alphab et every character consists of parts of the six dots basic form with tworows of three dots Numb er and combination of the dots are dierent for the several characters and stops numbers have the same comp osition as characters a j Braille is read from left to right with the tips of the forengers The left forenger lightens to nd out the next line -

High-Level and Low-Level Synthesis

c01.qxd 1/29/05 15:24 Page 17 1 High-Level and Low-Level Synthesis 1.1 Differentiating Between Low-Level and High-Level Synthesis We need to differentiate between low- and high-level synthesis. Linguistics makes a broadly equivalent distinction in terms of human speech production: low-level synthesis corresponds roughly to phonetics and high-level synthesis corresponds roughly to phonology. There is some blurring between these two components, and we shall discuss the importance of this in due course (see Chapter 11 and Chapter 25). In linguistics, phonology is essentially about planning. It is here that the plan is put together for speaking utterances formulated by other parts of the linguistics, like semantics and syn- tax. These other areas are not concerned with speaking–their domain is how to arrive at phrases and sentences which appropriately reflect the meaning of what a person has to say. It is felt that it is only when these pre-speech phrases and sentences are arrived at that the business of planning how to speak them begins. One reason why we feel that there is somewhat of a break between sentences and planning how to speak them is that those same sentences might be channelled into a part of linguistics which would plan how to write them. Diagrammed this looks like: graphology writing plan semantics/syntax phrase/sentence phonology speaking plan The task of phonology is to formulate a speaking plan, whereas that of graphology is to formulate a writing plan. Notice that in either case we end up simply with a plan–not with writing or speech: that comes later. -

How to Speak Emoji : a Guide to Decoding Digital Language Pdf, Epub, Ebook

HOW TO SPEAK EMOJI : A GUIDE TO DECODING DIGITAL LANGUAGE PDF, EPUB, EBOOK National Geographic Kids | 176 pages | 05 Apr 2018 | HarperCollins Publishers | 9780007965014 | English | London, United Kingdom How to Speak Emoji : A Guide to Decoding Digital Language PDF Book Secondary Col 2. Primary Col 1. Emojis are everywhere on your phone and computer — from winky faces to frowns, cats to footballs. They might combine a certain face with a particular arrow and the skull emoji, and it means something specific to them. Get Updates. Using a winking face emoji might mean nothing to us, but our new text partner interprets it as flirty. And yet, once he Parenting in the digital age is no walk in the park, but keep this in mind: children and teens have long used secret languages and symbols. However, not all users gave a favourable response to emojis. Black musicians, particularly many hip-hop artists, have contributed greatly to the evolution of language over time. A collection of poems weaving together astrology, motherhood, music, and literary history. Here begins the new dawn in the evolution the language of love: emoji. She starts planning how they will knock down the wall between them to spend more time together. Irrespective of one's political standpoint, one thing was beyond dispute: this was a landmark verdict, one that deserved to be reported and analysed with intelligence - and without bias. Though somewhat If a guy likes you, he's going to make sure that any opportunity he has to see you, he will. Here and Now Here are 10 emoticons guys use only when they really like you! So why do they do it? The iOS 6 software. -

Sounds to Graphemes Guide

David Newman – Speech-Language Pathologist Sounds to Graphemes Guide David Newman S p e e c h - Language Pathologist David Newman – Speech-Language Pathologist A Friendly Reminder © David Newmonic Language Resources 2015 - 2018 This program and all its contents are intellectual property. No part of this publication may be stored in a retrieval system, transmitted or reproduced in any way, including but not limited to digital copying and printing without the prior agreement and written permission of the author. However, I do give permission for class teachers or speech-language pathologists to print and copy individual worksheets for student use. Table of Contents Sounds to Graphemes Guide - Introduction ............................................................... 1 Sounds to Grapheme Guide - Meanings ..................................................................... 2 Pre-Test Assessment .................................................................................................. 6 Reading Miscue Analysis Symbols .............................................................................. 8 Intervention Ideas ................................................................................................... 10 Reading Intervention Example ................................................................................. 12 44 Phonemes Charts ................................................................................................ 18 Consonant Sound Charts and Sound Stimulation .................................................... -

Parietal Dysgraphia: Characterization of Abnormal Writing Stroke Sequences, Character Formation and Character Recall

Behavioural Neurology 18 (2007) 99–114 99 IOS Press Parietal dysgraphia: Characterization of abnormal writing stroke sequences, character formation and character recall Yasuhisa Sakuraia,b,∗, Yoshinobu Onumaa, Gaku Nakazawaa, Yoshikazu Ugawab, Toshimitsu Momosec, Shoji Tsujib and Toru Mannena aDepartment of Neurology, Mitsui Memorial Hospital, Tokyo, Japan bDepartment of Neurology, Graduate School of Medicine, University of Tokyo, Tokyo, Japan cDepartment of Radiology, Graduate School of Medicine, University of Tokyo, Tokyo, Japan Abstract. Objective: To characterize various dysgraphic symptoms in parietal agraphia. Method: We examined the writing impairments of four dysgraphia patients from parietal lobe lesions using a special writing test with 100 character kanji (Japanese morphograms) and their kana (Japanese phonetic writing) transcriptions, and related the test performance to a lesion site. Results: Patients 1 and 2 had postcentral gyrus lesions and showed character distortion and tactile agnosia, with patient 1 also having limb apraxia. Patients 3 and 4 had superior parietal lobule lesions and features characteristic of apraxic agraphia (grapheme deformity and a writing stroke sequence disorder) and character imagery deficits (impaired character recall). Agraphia with impaired character recall and abnormal grapheme formation were more pronounced in patient 4, in whom the lesion extended to the inferior parietal, superior occipital and precuneus gyri. Conclusion: The present findings and a review of the literature suggest that: (i) a postcentral gyrus lesion can yield graphemic distortion (somesthetic dysgraphia), (ii) abnormal grapheme formation and impaired character recall are associated with lesions surrounding the intraparietal sulcus, the symptom being more severe with the involvement of the inferior parietal, superior occipital and precuneus gyri, (iii) disordered writing stroke sequences are caused by a damaged anterior intraparietal area. -

Haptiread: Reading Braille As Mid-Air Haptic Information

HaptiRead: Reading Braille as Mid-Air Haptic Information Viktorija Paneva Sofia Seinfeld Michael Kraiczi Jörg Müller University of Bayreuth, Germany {viktorija.paneva, sofia.seinfeld, michael.kraiczi, joerg.mueller}@uni-bayreuth.de Figure 1. With HaptiRead we evaluate for the first time the possibility of presenting Braille information as touchless haptic stimulation using ultrasonic mid-air haptic technology. We present three different methods of generating the haptic stimulation: Constant, Point-by-Point and Row-by-Row. (a) depicts the standard ordering of cells in a Braille character, and (b) shows how the character in (a) is displayed by the three proposed methods. HaptiRead delivers the information directly to the user, through their palm, in an unobtrusive manner. Thus the haptic display is particularly suitable for messages communicated in public, e.g. reading the departure time of the next bus at the bus stop (c). ABSTRACT Author Keywords Mid-air haptic interfaces have several advantages - the haptic Mid-air Haptics, Ultrasound, Haptic Feedback, Public information is delivered directly to the user, in a manner that Displays, Braille, Reading by Blind People. is unobtrusive to the immediate environment. They operate at a distance, thus easier to discover; they are more hygienic and allow interaction in 3D. We validate, for the first time, in INTRODUCTION a preliminary study with sighted and a user study with blind There are several challenges that blind people face when en- participants, the use of mid-air haptics for conveying Braille. gaging with interactive systems in public spaces. Firstly, it is We tested three haptic stimulation methods, where the hap- more difficult for the blind to maintain their personal privacy tic feedback was either: a) aligned temporally, with haptic when engaging with public displays. -

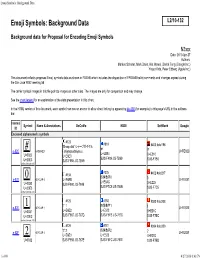

Emoji Symbols: Background Data

Emoji Symbols: Background Data Emoji Symbols: Background Data Background data for Proposal for Encoding Emoji Symbols N3xxx Date: 2010-Apr-27 Authors: Markus Scherer, Mark Davis, Kat Momoi, Darick Tong (Google Inc.) Yasuo Kida, Peter Edberg (Apple Inc.) This document reflects proposed Emoji symbols data as shown in FDAM8 which includes the disposition of FPDAM8 ballot comments and changes agreed during the San José WG2 meeting 56. The carrier symbol images in this file point to images on other sites. The images are only for comparison and may change. See the chart legend for an explanation of the data presentation in this chart. In the HTML version of this document, each symbol row has an anchor to allow direct linking by appending #e-4B0 (for example) to this page's URL in the address bar. Internal Symbol Name & Annotations DoCoMo KDDI SoftBank Google ID Enclosed alphanumeric symbols #123 #818 'Sharp dial' シャープダイヤル #403 #old196 # # # e-82C ⃣ HASH KEY 「shiyaapudaiyaru」 U+FE82C U+EB84 U+0023 U+E6E0 U+E210 SJIS-F489 JIS-7B69 U+20E3 SJIS-F985 JIS-7B69 SJIS-F7B0 unified (Unicode 3.0) #325 #134 #402 #old217 0 四角数字0 0 e-837 ⃣ KEYCAP 0 U+E6EB U+FE837 U+E5AC U+0030 SJIS-F990 JIS-784B U+E225 U+20E3 SJIS-F7C9 JIS-784B SJIS-F7C5 unified (Unicode 3.0) #125 #180 #393 #old208 1 '1' 1 四角数字1 1 e-82E ⃣ KEYCAP 1 U+FE82E U+0031 U+E6E2 U+E522 U+E21C U+20E3 SJIS-F987 JIS-767D SJIS-F6FB JIS-767D SJIS-F7BC unified (Unicode 3.0) #126 #181 #394 #old209 '2' 2 四角数字2 e-82F KEYCAP 2 2 U+FE82F 2⃣ U+E6E3 U+E523 U+E21D U+0032 SJIS-F988 JIS-767E SJIS-F6FC JIS-767E SJIS-F7BD -

ISO/IEC JTC1/SC2/WG2 N 2005 Date: 1999-05-29

ISO INTERNATIONAL ORGANIZATION FOR STANDARDIZATION ORGANISATION INTERNATIONALE DE NORMALISATION --------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- ISO/IEC JTC1/SC2/WG2 Universal Multiple-Octet Coded Character Set (UCS) -------------------------------------------------------------------------------- ISO/IEC JTC1/SC2/WG2 N 2005 Date: 1999-05-29 TITLE: ISO/IEC 10646-1 Second Edition text, Draft 2 SOURCE: Bruce Paterson, project editor STATUS: Working paper of JTC1/SC2/WG2 ACTION: For review and comment by WG2 DISTRIBUTION: Members of JTC1/SC2/WG2 1. Scope This paper provides a second draft of the text sections of the Second Edition of ISO/IEC 10646-1. It replaces the previous paper WG2 N 1796 (1998-06-01). This draft text includes: - Clauses 1 to 27 (replacing the previous clauses 1 to 26), - Annexes A to R (replacing the previous Annexes A to T), and is attached here as “Draft 2 for ISO/IEC 10646-1 : 1999” (pages ii & 1 to 77). Published and Draft Amendments up to Amd.31 (Tibetan extended), Technical Corrigenda nos. 1, 2, and 3, and editorial corrigenda approved by WG2 up to 1999-03-15, have been applied to the text. The draft does not include: - character glyph tables and name tables (these will be provided in a separate WG2 document from AFII), - the alphabetically sorted list of character names in Annex E (now Annex G), - markings to show the differences from the previous draft. A separate WG2 paper will give the editorial corrigenda applied to this text since N 1796. The editorial corrigenda are as agreed at WG2 meetings #34 to #36. Editorial corrigenda applicable to the character glyph tables and name tables, as listed in N1796 pages 2 to 5, have already been applied to the draft character tables prepared by AFII.