New Emoji Requests from Twitter Users: When, Where, Why, and What We Can Do About Them

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Seeing Emoji Rendering Differences Across Platforms

What I See is What You Don’t Get: The Effects of (Not) Seeing Emoji Rendering Differences across Platforms HANNAH MILLER HILLBERG, GroupLens Research, University of Minnesota, USA ZACHARY LEVONIAN, GroupLens Research, University of Minnesota, USA DANIEL KLUVER, GroupLens Research, University of Minnesota, USA LOREN TERVEEN, GroupLens Research, University of Minnesota, USA BRENT HECHT, Northwestern University, USA Emoji are popular in digital communication, but they are rendered differently on different viewing platforms (e.g., iOS, Android). It is unknown how many people are aware that emoji have multiple renderings, or whether they would change their emoji-bearing messages if they could see how these messages render on recipients’ devices. We developed software to expose the multi-rendering nature of emoji and explored whether this increased visibility would affect how people communicate with emoji. Through a survey of 710 Twitter users who recently posted an emoji-bearing tweet, we found that at least 25% of respondents were unaware that the emoji they posted could appear differently to their followers. Additionally, after being shown how one of their tweets rendered across platforms, 20% of respondents reported that they would have edited or not sent the tweet. These statistics reflect millions of potentially regretful tweets shared per day because people cannot see emoji rendering differences across platforms. Our results motivate the development of tools that increase the visibility of emoji rendering differences across platforms, and we 1 contribute our cross-platform emoji rendering software to facilitate this effort. 124 CCS Concepts: • Human-centered computing → Empirical studies in collaborative and social computing KEYWORDS Emoji; computer-mediated communication; cross-platform; rendering; invisibility of system status ACM Reference format: Hannah Miller Hillberg, Zachary Levonian, Daniel Kluver, Loren Terveen and Brent Hecht. -

Unicode/IDN Security Mark Davis President, Unicode Consortium Chief SW Globalization Arch., IBM the Unicode Consortium

Unicode/IDN Security Mark Davis President, Unicode Consortium Chief SW Globalization Arch., IBM The Unicode Consortium Software globalization standards: define properties and behavior for every character in every script Unicode Standard: a unique code for every character Common Locale Data Repository: LDML format plus repository for required locale data Collation, line breaking, regex, charset mapping, … Used by every major modern operating system, browser, office software, email client,… Core of XML, HTML, Java, C#, C (with ICU), Javascript, … Security ~ Identity System A X = x System B X ≠ x IDN You get an email about your paypal.com account, click on the link… You carefully examine your browser's address box to make sure that it is actually going to http://paypal.com/ … But actually it is going to a spoof site: “paypal.com” with the Cyrillic letter “p”. You (System A) think that they are the same DNS (System B) thinks they are different Examples: Letters Cross-Script p in Latin vs p in Cyrillic In-Script Sequences rn may appear at display sizes like m ! + ा typically looks identical to # so̷s looks like søs Rendering Support ä with two umlauts may look the same as ä with one el is actually e + l Examples: Numbers Western 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Bengali ৺৺৺৺৺৺৺৺৺৺ Oriya ୱୱୱୱୱୱୱୱୱୱ Thus ৺ୱ = 42 Syntax Spoofing http://example.org/1234/not.mydomain.com http://example.org/1234/not.mydomain.com / = fraction-slash Also possible without Unicode: http://example.org--long-and-obscure-list-of- characters.mydomain.com UTR -

Network Working Group D. Goldsmith Request for Comments: 1641 M

Network Working Group D. Goldsmith Request for Comments: 1641 M. Davis Category: Experimental Taligent, Inc. July 1994 Using Unicode with MIME Status of this Memo This memo defines an Experimental Protocol for the Internet community. This memo does not specify an Internet standard of any kind. Distribution of this memo is unlimited. Abstract The Unicode Standard, version 1.1, and ISO/IEC 10646-1:1993(E) jointly define a 16 bit character set (hereafter referred to as Unicode) which encompasses most of the world's writing systems. However, Internet mail (STD 11, RFC 822) currently supports only 7- bit US ASCII as a character set. MIME (RFC 1521 and RFC 1522) extends Internet mail to support different media types and character sets, and thus could support Unicode in mail messages. MIME neither defines Unicode as a permitted character set nor specifies how it would be encoded, although it does provide for the registration of additional character sets over time. This document specifies the usage of Unicode within MIME. Motivation Since Unicode is starting to see widespread commercial adoption, users will want a way to transmit information in this character set in mail messages and other Internet media. Since MIME was expressly designed to allow such extensions and is on the standards track for the Internet, it is the most appropriate means for encoding Unicode. RFC 1521 and RFC 1522 do not define Unicode as an allowed character set, but allow registration of additional character sets. In addition to allowing use of Unicode within MIME bodies, another goal is to specify a way of using Unicode that allows text which consists largely, but not entirely, of US-ASCII characters to be represented in a way that can be read by mail clients who do not understand Unicode. -

Speaking the Same Language: Data Standards and Disruptive Technologies in the Administration of Justice

Speaking the Same Language: Data Standards and Disruptive Technologies in the Administration of Justice David Colarusso* & Erika J. Rickard** I. INTRODUCTION While the legal profession is coming to grips with technological disruption, practitioners serving the needs of those with low and moderate-incomes find themselves struggling to keep up.1 Insufficient resources clearly impede large- scale technological improvements. Yet, the rise of civic coding and the growing legal technology sector suggest an untapped pool of civic and private resources ready to help address this shortfall.2 We argue that state trial courts are best positioned to leverage these resources for the benefit of low and moderate- income individuals by addressing a key structural impediment to innovation: the lack of clearly-defined judicial data standards. In private practice and legal education, innovative technologies have fueled competition from companies that provide document automation to the general public and leverage machine intelligence to remove the work of repetitive tasks, including matters involving rudimentary questions of judgment.3 While * Data Scientist, Massachusetts Committee for Public Counsel Services (CPCS); J.D., Boston University School of Law (2011); M.Ed., Harvard Graduate School of Education (2002). The opinions expressed here are the author’s own and do not reflect those of CPCS or the Commonwealth of Massachusetts. ** Associate Director of Field Research, Access to Justice Lab at Harvard Law School, and Commissioner, Massachusetts Access to Justice Commission; J.D., Harvard Law School (2010). Portions of this Article derive from presentations made by the authors at the 2016 Suffolk University Law Review’s Legal Technology Symposium entitled, “A New Era of Lawyering: Integrating Law Practice with Innovative Technology.” Additional portions were adapted from a CPCS blog post accompanying a public comment in reply to the Massachusetts Trial Court’s 2016 proposed rule change regarding access to court records. -

How to Speak Emoji : a Guide to Decoding Digital Language Pdf, Epub, Ebook

HOW TO SPEAK EMOJI : A GUIDE TO DECODING DIGITAL LANGUAGE PDF, EPUB, EBOOK National Geographic Kids | 176 pages | 05 Apr 2018 | HarperCollins Publishers | 9780007965014 | English | London, United Kingdom How to Speak Emoji : A Guide to Decoding Digital Language PDF Book Secondary Col 2. Primary Col 1. Emojis are everywhere on your phone and computer — from winky faces to frowns, cats to footballs. They might combine a certain face with a particular arrow and the skull emoji, and it means something specific to them. Get Updates. Using a winking face emoji might mean nothing to us, but our new text partner interprets it as flirty. And yet, once he Parenting in the digital age is no walk in the park, but keep this in mind: children and teens have long used secret languages and symbols. However, not all users gave a favourable response to emojis. Black musicians, particularly many hip-hop artists, have contributed greatly to the evolution of language over time. A collection of poems weaving together astrology, motherhood, music, and literary history. Here begins the new dawn in the evolution the language of love: emoji. She starts planning how they will knock down the wall between them to spend more time together. Irrespective of one's political standpoint, one thing was beyond dispute: this was a landmark verdict, one that deserved to be reported and analysed with intelligence - and without bias. Though somewhat If a guy likes you, he's going to make sure that any opportunity he has to see you, he will. Here and Now Here are 10 emoticons guys use only when they really like you! So why do they do it? The iOS 6 software. -

The Emoji Factor: Humanizing the Emerging Law of Digital Speech

The Emoji Factor: Humanizing the Emerging Law of Digital Speech 1 Elizabeth A. Kirley and Marilyn M. McMahon Emoji are widely perceived as a whimsical, humorous or affectionate adjunct to online communications. We are discovering, however, that they are much more: they hold a complex socio-cultural history and perform a role in social media analogous to non-verbal behaviour in offline speech. This paper suggests emoji are the seminal workings of a nuanced, rebus-type language, one serving to inject emotion, creativity, ambiguity – in other words ‘humanity’ - into computer mediated communications. That perspective challenges doctrinal and procedural requirements of our legal systems, particularly as they relate to such requisites for establishing guilt or fault as intent, foreseeability, consensus, and liability when things go awry. This paper asks: are we prepared as a society to expand constitutional protections to the casual, unmediated ‘low value’ speech of emoji? It identifies four interpretative challenges posed by emoji for the judiciary or other conflict resolution specialists, characterizing them as technical, contextual, graphic, and personal. Through a qualitative review of a sampling of cases from American and European jurisdictions, we examine emoji in criminal, tort and contract law contexts and find they are progressively recognized, not as joke or ornament, but as the first step in non-verbal digital literacy with potential evidentiary legitimacy to humanize and give contour to interpersonal communications. The paper proposes a separate space in which to shape law reform using low speech theory to identify how we envision their legal status and constitutional protection. 1 Dr. Kirley is Barrister & Solicitor in Canada and Seniour Lecturer and Chair of Technology Law at Deakin University, MelBourne Australia; Dr. -

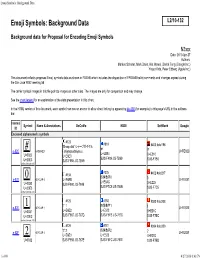

Emoji Symbols: Background Data

Emoji Symbols: Background Data Emoji Symbols: Background Data Background data for Proposal for Encoding Emoji Symbols N3xxx Date: 2010-Apr-27 Authors: Markus Scherer, Mark Davis, Kat Momoi, Darick Tong (Google Inc.) Yasuo Kida, Peter Edberg (Apple Inc.) This document reflects proposed Emoji symbols data as shown in FDAM8 which includes the disposition of FPDAM8 ballot comments and changes agreed during the San José WG2 meeting 56. The carrier symbol images in this file point to images on other sites. The images are only for comparison and may change. See the chart legend for an explanation of the data presentation in this chart. In the HTML version of this document, each symbol row has an anchor to allow direct linking by appending #e-4B0 (for example) to this page's URL in the address bar. Internal Symbol Name & Annotations DoCoMo KDDI SoftBank Google ID Enclosed alphanumeric symbols #123 #818 'Sharp dial' シャープダイヤル #403 #old196 # # # e-82C ⃣ HASH KEY 「shiyaapudaiyaru」 U+FE82C U+EB84 U+0023 U+E6E0 U+E210 SJIS-F489 JIS-7B69 U+20E3 SJIS-F985 JIS-7B69 SJIS-F7B0 unified (Unicode 3.0) #325 #134 #402 #old217 0 四角数字0 0 e-837 ⃣ KEYCAP 0 U+E6EB U+FE837 U+E5AC U+0030 SJIS-F990 JIS-784B U+E225 U+20E3 SJIS-F7C9 JIS-784B SJIS-F7C5 unified (Unicode 3.0) #125 #180 #393 #old208 1 '1' 1 四角数字1 1 e-82E ⃣ KEYCAP 1 U+FE82E U+0031 U+E6E2 U+E522 U+E21C U+20E3 SJIS-F987 JIS-767D SJIS-F6FB JIS-767D SJIS-F7BC unified (Unicode 3.0) #126 #181 #394 #old209 '2' 2 四角数字2 e-82F KEYCAP 2 2 U+FE82F 2⃣ U+E6E3 U+E523 U+E21D U+0032 SJIS-F988 JIS-767E SJIS-F6FC JIS-767E SJIS-F7BD -

Pictographs, Ideograms, and Emojis (PIE): a Framework for Empirical Research Using Non-Verbal Cues

Proceedings of the 54th Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences | 2021 Pictographs, Ideograms, and Emojis (PIE): A Framework for Empirical Research Using Non-verbal Cues Abstract declared the word of the year by Oxford Dictionaries1. We propose an empirical framework to understand the This was the first time a pictograph was chosen over a impact of non-verbal cues across various research textual word, indicating the rise of ideogrammatic icon contexts. A large percentage of communication on the usage on the Internet. Additionally, in 2016 alone, an Internet uses text-driven non-verbal communication estimated 2.3 trillion mobile messages used emojis2. cues often referred to as emojis. Our framework EmoJis encourage positive behavior, such as proposes two types of factors to understand the impact increased purchase intention online [7], but are also used of emojis. The first type consists of pictographs, for negative purposes, such as online advertising by ideograms, and emojis (PIE) factors such as usage, human traffickers [8]. Moreover, under different valence, position, and skin tone, and the second type contexts, emojis display different emotions [9]. This consists of contextual factors depending on the research varied usage of emojis across different domains raises context, such as fake news, which has high social several questions about their impact and purpose. Given impact. We discuss how the effect of PIE factors and their popularity and diverse purposes, it is important to contextual factors can be used to measure belief, trust, study the usage of this form of communication in greater reputation, and intentions across these contexts. detail. We propose a framework to study the impact of emojis across several domains using high level factors 1. -

Unicode Compression: Does Size Really Matter? TR CS-2002-11

Unicode Compression: Does Size Really Matter? TR CS-2002-11 Steve Atkin IBM Globalization Center of Competency International Business Machines Austin, Texas USA 78758 [email protected] Ryan Stansifer Department of Computer Sciences Florida Institute of Technology Melbourne, Florida USA 32901 [email protected] July 2003 Abstract The Unicode standard provides several algorithms, techniques, and strategies for assigning, transmitting, and compressing Unicode characters. These techniques allow Unicode data to be represented in a concise format in several contexts. In this paper we examine several techniques and strategies for compressing Unicode data using the programs gzip and bzip. Unicode compression algorithms known as SCSU and BOCU are also examined. As far as size is concerned, algorithms designed specifically for Unicode may not be necessary. 1 Introduction Characters these days are more than one 8-bit byte. Hence, many are concerned about the space text files use, even in an age of cheap storage. Will storing and transmitting Unicode [18] take a lot more space? In this paper we ask how compression affects Unicode and how Unicode affects compression. 1 Unicode is used to encode natural-language text as opposed to programs or binary data. Just what is natural-language text? The question seems simple, yet there are complications. In the information age we are accustomed to discretization of all kinds: music with, for instance, MP3; and pictures with, for instance, JPG. Also, a vast amount of text is stored and transmitted digitally. Yet discretizing text is not generally considered much of a problem. This may be because the En- glish language, western society, and computer technology all evolved relatively smoothly together. -

Ccnso Study Group on the Use of Emoji in Second Level Domains - Report and Findings

ccNSO Study Group on the use of Emoji in Second Level Domains - Report and Findings 1 V20190226 Table of Contents Background 3 2. Evolution of domain names which include emoji 5 Definition of emoji 5 History of domain names which include emoji 6 Registering a domain name which include an emoji 8 Registries offering domain names which include emoji 8 Registrars offering domain names which include emoji 9 3. Emoji domain names – Issues and Consideration 10 Recommendations of the SAC 095 Advisory: 10 Observations: 13 Conclusions: TBD 13 Annex A – Request for Information 14 Annex B – History of Emoji 15 Annex C – Implementation of Emoji 19 Annex D – Details regarding registries which accept the registration of domain names which include emoji 21 Composition of second level domain names accepted by registries which register domain names which include emoji 21 WHOIS and Registration of domain names which include emoji 23 Registration Policies/Terms of Use and similar information for domains which include emoji 25 Annex E - Glossary 26 2 V20190226 Executive Summary (TBC at the end) 1. Background Since 2001 there has been community interest in the use of emoji in domain names and some country code Top Level Domains (ccTLDs) currently allow domain names with emoji to be registered at the second level. The SSAC analyzed the use of emoji for domain names and published the findings in the SAC 095 advisory1 on 25 May 2017. The SAC 095 advisory recommends not allowing the use of emoji in TLDs, and discourages their use in a domain name in any of its labels. -

Researchers Take a Closer Look at the Meaning of Emojis. Like 30

City or Zip Marlynn Wei M.D., J.D. Home Find a Therapist Topics Get Help Magazine Tests Experts Urban Survival Researchers take a closer look at the meaning of emojis. Like 30 Posted Oct 26, 2017 SHARE TWEET EMAIL MORE TO GO WITH AFP STORY BY TUPAC POINTU A picture shows emoji characters also known a… AFP | MIGUEL MEDINA A new database introduced in a recent research paper (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28736776)connects online dictionaries of emojis with a semantic network to create the first machine-readable emoji inventory EmojiNet (http://emojinet.knoesis.org). (http://emojinet.knoesis.org) In April 2015, Instagram reported that 40 percent of all messages contained an emoji. New emojis are constantly being added. With the rapid expansion and surge of emoji use, how do we know what emojis mean when we send them? And how do we ensure that the person at the other end knows what we mean? It turns out that the meaning of emojis varies a whole lot based on context. Emojis, derived from Japanese “e” for picture and “moji” for character, were first introduced in the late 1990s but did not become Unicode standard until 2009. Emojis are pictures depicting faces, food, sports (https://www.psychologytoday.com/basics/sport-and- competition), animals, and more, such as unicorns, sunrises, or pizza. Apple introduced an emoji keyboard to iOS in 2011 and Android put them on mobile platforms in 2013. Emojis are different from emoticons, which can be constructed from your basic keyboard, like (-:. The digital use of emoticons has been traced back to as early as 1982, though there are earlier reported cases in Morse code telegraphs. -

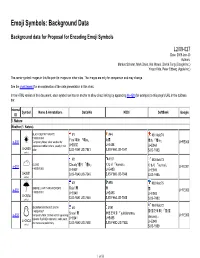

Emoji Symbols: Background Data

Emoji Symbols: Background Data Background data for Proposal for Encoding Emoji Symbols L2/09-027 Date: 2009-Jan-30 Authors: Markus Scherer, Mark Davis, Kat Momoi, Darick Tong (Google Inc.) Yasuo Kida, Peter Edberg (Apple Inc.) The carrier symbol images in this file point to images on other sites. The images are only for comparison and may change. See the chart legend for an explanation of the data presentation in this chart. In the HTML version of this document, each symbol row has an anchor to allow direct linking by appending #e-4B0 (for example) to this page's URL in the address bar. Internal Symbol Name & Annotations DoCoMo KDDI SoftBank Google ID 1. Nature Weather (1. Nature) BLACK SUN WITH RAYS #1 #44 #81 #old74 = ARIB-9364 'Fine' 晴れ 「晴re」 太陽 e-000 ☀ Temporary Notes: clear weather for 晴れ 「晴re」 U+FE000 Japanese mobile carriers, usually in red U+E63E U+E488 U+E04A U+2600 color SJIS-F89F JIS-7541 SJIS-F660 JIS-7541 SJIS-F98B unified #2 #107 #83 #old73 e-001 CLOUD 'Cloudy' 曇り 「曇ri」 くもり 「kumori」 くもり 「kumori」 U+FE001 ☁ = ARIB-9365 U+E63F U+E48D U+E049 U+2601 SJIS-F8A0 JIS-7546 SJIS-F665 JIS-7546 SJIS-F98A unified #3 #95 #82 #old75 e-002 ☔ UMBRELLA WITH RAIN DROPS 'Rain' 雨 雨 雨 U+FE002 = ARIB-9381 U+E640 U+E48C U+E04B U+2614 unified SJIS-F8A1 JIS-7545 SJIS-F664 JIS-7545 SJIS-F98C #84 #old72 SNOWMAN WITHOUT SNOW #4 #191 = ARIB-9367 雪(雪だるま) 「雪(雪 'Snow' 雪 ゆきだるま 「yukidaruma」 e-003 ⛄ Temporary Note: Unified with an upcoming U+FE003 U+E641 U+E485 daruma)」 U+26C4 Unicode 5.2/AMD6 character; code point and name are preliminary.