Final Copy 2021 01 21 Smith

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Buyer's Guide to Loudspeakers 2017

CONTENTS • FROM THE EDITOR • ON THE HORIZON • BOOK FEATURE • HOW TO CHOOSE A LOUDSPEAKER • DESKTOP & POWERED • BOOKSHELF, STAND-MOUNT • FLOORSTANDING <$10K • FLOORSTANDING >$10K • SUBWOOFERS Buyer’s Guide to Loudspeakers 2017 SPONSORED BY A MASTERPIECE OF DESIGN AND ENGINEERING Renaissance ESL 15A represents a major evolution in electrostatic design. A 15-inch Curvilinear Line Source (CLS™) XStat™ vacuum-bonded electrostatic transducer with advanced MicroPerf ™ stator technology and ultra-rigid AirFrame™ Blade construction provide the heart of this exceptional loudspeaker. A powerfully dynamic low-frequency experience is rendered with unfl inching accuracy and authority courtesy of dual 12-inch low-distortion aluminum cone woofers. Each woofer is independently powered by a 500-watt Class-D amplifi er, and controlled by a 24-Bit Vojtko™ DSP Engine featuring Anthem Room Correction (ARC™) technology. Hear it today at your local dealer. 1 Buyer’s Guide to Loudspeakers 2017 the absolute sound MartinLogan_DLR_TAS_Renaissance_ESL15A_Buyer's_Guide_SPREAD_2016.indd 1 2016-03-15 7:49 AM 2 Buyer’s Guide to Loudspeakers 2017 the absolute sound Click here to go to that section CONTENTS • FROM THE EDITOR • ON THE HORIZON • BOOK FEATURE • HOW TO CHOOSE A LOUDSPEAKER • DESKTOP & POWERED • BOOKSHELF, STAND-MOUNT • FLOORSTANDING <$10K • FLOORSTANDING >$10K • SUBWOOFERS Contents SPONSORED BY You can’t tell anything about the loudspeaker until you listen to it. Don’t be in a hurry to buy the first speaker you like; audition several products. A MASTERPIECE OF DESIGN AND ENGINEERING Renaissance ESL 15A represents a major evolution in electrostatic design. FROM THE EDITOR ON THE HORIZON HOW TO CHOOSE A LOUDSPEAKER A 15-inch Curvilinear Line Source (CLS™) XStat™ vacuum-bonded electrostatic transducer with advanced MicroPerf ™ stator technology and ultra-rigid Julie Mullins welcomes you to our Neil Gader has the scoop on the Robert Harley helps you navigate the tricky process of speaker auditioning AirFrame™ Blade construction provide the heart of this exceptional loudspeaker. -

Remote Sensing and Geotechnical Investigations of Expansive Soils Dr. Fekerte Arega Yitagesu 2012

REMOTE SENSING AND GEOTECHNICAL INVESTIGATIONS OF EXPANSIVE SOILS Fekerte Arega Yitagesu Examining committee: Prof.dr. V.G. Jetten University of Twente, ITC Prof.dr.ir. A. Stein University of Twente, ITC Prof.dr. S.M. de Jong Utrecht University Prof.dr. E. Pirard University of Liège, Belgium Dr. S. Chabrillat GFZ German Research Centre for Geosciences ITC dissertation number 201 ITC, P.O. Box 6, 7500 AA Enschede, The Netherlands ISBN 978-90-6164-326-5 Cover designed by Demeke Ashenafi and Job Duim Printed by ITC Printing Department Copyright © 2012 by Fekerte Arega Yitagesu REMOTE SENSING AND GEOTECHNICAL INVESTIGATIONS OF EXPANSIVE SOILS DISSERTATION to obtain the degree of doctor at the University of Twente, on the authority of the Rector Magnificus, prof.dr. H. Brinksma, on account of the decision of the graduation committee, to be publicly defended on Wednesday March 28, 2012 at 14:45 hrs by Fekerte Arega Yitagesu born on February 16, 1975 in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia This thesis is approved by Prof. Dr. F.D. van der Meer, promoter Dr. H.M.A. van der Werff, assistant promoter Dedicated to my beloved mom! Acknowledgements What a precious aptitude (this research)! I have sojourned my PhD journey seemingly alone, but undoubtedly in support and collaboration with numerous individuals and organizations. I would like to take this opportunity to express my most sincere acknowledgments to all who contributed to bring this work to fruition. First and foremost, I would like to pay my deepest respect and utmost gratitude to my promoter prof. Dr. Freek van der Meer. -

Heritage Regimes and the State Universitätsverlag Göttingen Cultural Property, Volume 6 Ed

hat happens when UNESCO heritage conventions are ratifi ed by a state? 6 WHow do UNESCO’s global efforts interact with preexisting local, regional and state efforts to conserve or promote culture? What new institutions emerge to address the mandate? The contributors to this volume focus on the work of translation and interpretation that ensues once heritage conventions are ratifi ed and implemented. With seventeen case studies from Europe, Africa, the Carib- bean and China, the volume provides comparative evidence for the divergent heritage regimes generated in states that differ in history and political orga- nization. The cases illustrate how UNESCO’s aspiration to honor and celebrate cultural diversity diversifi es itself. The very effort to adopt a global heritage regime forces myriad adaptations to particular state and interstate modalities of Heritage Regimes building and managing heritage. and the State ed. by Regina F. Bendix, Aditya Eggert Heritage Regimes and the State and Arnika Peselmann Göttingen Studies in Cultural Property, Volume 6 Regina F. Bendix, Aditya Eggert and Arnika Peselmann ISBN: 978-3-86395-075-0 ISSN: 2190-8672 Universitätsverlag Göttingen Universitätsverlag Göttingen Regina F. Bendix, Aditya Eggert, Arnika Peselmann (Eds.) Heritage Regimes and the State This work is licensed under the Creative Commons License 3.0 “by-nd”, allowing you to download, distribute and print the document in a few copies for private or educational use, given that the document stays unchanged and the creator is mentioned. Published in 2012 by Universitätsverlag Göttingen as volume 6 in the series “Göttingen Studies in Cultural Property” Heritage Regimes and the State Edited by Regina F. -

Underground Club Spaces and Interactive Performance

Underground Club Spaces and Interactive Performance: How might underground club spaces be read and developed as new environments for democratic/participatory/interactive performance and how are these performative spaces of play created, navigated and utilised by those who inhabit them? Kathleen Alice O‟Grady Submitted in accordance with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Leeds School of Performance and Cultural Industries December 2009 The candidate confirms that the work submitted is her own and that appropriate credit has been given where reference has been made to the work of others. This copy has been supplied on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from the thesis may be published without proper acknowledgement. Acknowledgements This thesis is dedicated to my parents who have always believed in me and to my daughter, Maisie, who is my source of inspiration and joy. Gratitude goes to my PhD supervisors Professor Mick Wallis and Dr Martin Crick, both of whom have given me continued support and guidance throughout this research. Thanks also to my colleagues and my students at the School of Performance and Cultural Industries who have encouraged me and kept me going with their sense of humour, wise words and loyalty. Thank you to all the club and festival organizers that have allowed me access to their events, particularly those involved with Planet Angel, Synergy, Duckie, Riff Raff, Planet Zogg, Speedqueen, Manumission, Shamania, Beatherder, Nozstock and Solfest. Special gratitude to Fatmoon Psychedelic Playgrounds for allowing me the room to move creatively and to develop this practice in a supportive environment. -

Musical Innovation, Collaboration, and Ideological Expression in the Chilean Netlabel Movement

Sharing Sounds: Musical Innovation, Collaboration, and Ideological Expression in the Chilean Netlabel Movement by James Ryan Bodiford A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Music: Musicology) in the University of Michigan 2017 Dissertation Committee: Associate Professor Christi-Anne Castro, Chair Professor Kelly Askew Professor Charles H. Garrett Assistant Professor Meilu Ho Professor Bruce Mannheim James Ryan Bodiford [email protected] ORCID iD: 0000-0002-9850-0438 © James Ryan Bodiford 2017 Dedicated to all those musicians who have devoted their work to imagining a better world… ii Table of Contents Dedication ii List of Figures vi Abstract viii Chapter I – Introduction: Sharing Sounds 1 A Shifting Paradigm 10 The Transnational Netlabel Movement and its Chilean Variant 14 Art World Reformation 20 Social Discourse, Collaboration, and Collectivism 23 Experimentalism, Ideology, and Social Movements 29 Methodology 34 Chapter Summaries 36 Chapter II – “This Disc Is Culture”: Mass Media Hegemony and Its Subversion in Chilean Musical Culture, 1965-2000 39 Mass Media Hegemony and the Culture Industry 44 Social Activism and Subversion 58 DICAP, Unidad Popular and the Emergence of Nueva Canción 1965-1973 64 Musical Dissemination Under Dictatorship (1973-1989): Alerce, Clandestine Cassette Distribution 80 Democratic Re-Transition and Post-Dictatorship Transformations in the Chilean Music Industry 1990-2000 96 iii Chapter III – “My Music Is Not A Business”: New Media Transformations -

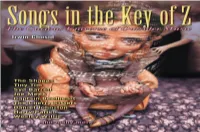

Songs in the Key of Z

covers complete.qxd 7/15/08 9:02 AM Page 1 MUSIC The first book ever about a mutant strain ofZ Songs in theKey of twisted pop that’s so wrong, it’s right! “Iconoclast/upstart Irwin Chusid has written a meticulously researched and passionate cry shedding long-overdue light upon some of the guiltiest musical innocents of the twentieth century. An indispensable classic that defines the indefinable.” –John Zorn “Chusid takes us through the musical looking glass to the other side of the bizarro universe, where pop spelled back- wards is . pop? A fascinating collection of wilder cards and beyond-avant talents.” –Lenny Kaye Irwin Chusid “This book is filled with memorable characters and their preposterous-but-true stories. As a musicologist, essayist, and humorist, Irwin Chusid gives good value for your enter- tainment dollar.” –Marshall Crenshaw Outsider musicians can be the product of damaged DNA, alien abduction, drug fry, demonic possession, or simply sheer obliviousness. But, believe it or not, they’re worth listening to, often outmatching all contenders for inventiveness and originality. This book profiles dozens of outsider musicians, both prominent and obscure, and presents their strange life stories along with photographs, interviews, cartoons, and discographies. Irwin Chusid is a record producer, radio personality, journalist, and music historian. He hosts the Incorrect Music Hour on WFMU; he has produced dozens of records and concerts; and he has written for The New York Times, Pulse, New York Press, and many other publications. $18.95 (CAN $20.95) ISBN 978-1-55652-372-4 51895 9 781556 523724 SONGS IN THE KEY OF Z Songs in the Key of Z THE CURIOUS UNIVERSE OF O U T S I D E R MUSIC ¥ Irwin Chusid Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Chusid, Irwin. -

Letters of Adèle De Batz De Trenquelléon

Letters of Adèle de Batz de Trenquelléon Volume One: 1805-1816 Edited by Joseph Stefanelli, SM Translated by Joseph Roy, SM North American Center for Marianist Studies Dayton, OH Monograph Series—Document No. 41, Volume 1—1999 This work is an English translation from the French Lettres de Adèle de Batz de Trenquelléon: Fondatrice de l’Institut des Filles de Marie Immaculée, Marianistes, en collaboration avec le Père Guillaume Joseph Chaminade, Fondateur de la Société de Marie (Rome: Filles de Marie Immaculée, 1985). Copies of this work may be obtained from North American Center for Marianist Studies 4435 E. Patterson Road Dayton, OH 45430-1083 Printed by Marianist Press Cover icon: Colette Saunier Cover Design: Robert Hughes, SM Typesetting: Vanessa Blaylock Contents Editor’s Preface Summary Biography of Adèle Letters 1 to 304 Appendix One: Personal Rule of Life Appendix Two: Rule of the Association Appendix Three: The Actes Appendix Four: Concordance of Letters [not in electronic version] Appendix Five: Summary Table of Letters (1 to 304) Appendix Six: List of Religious and Secular Names Index to Persons Illustrations Adèle as a child Baron de Trenquelléon Baroness de Trenquelléon Map of the Southwest of France Château de Trenquelléon Chapel, Château de Trenquelléon Letter to Agathe Diché, April 10, 1806 William Joseph Chaminade Marie Thérèse Charlotte de Lamourous Editor’s Preface Adèle de Batz de Trenquelléon was a prolific correspondent. Most of what we know about her is garnered from her own letters. The actual number of letters she wrote was certainly in the thousands. Of them, only 737 have come down to us. -

The Harp in Jazz and American Pop Music Megan A. Bledsoe A

The Harp in Jazz and American Pop Music Megan A. Bledsoe A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts University of Washington 2012 Reading Committee: Donna Shin, Chair Valerie Muzzolini Gordon Áine Heneghan Program Authorized to Offer Degree: Harp Performance Bledsoe - DMA Harp Performance ©Copyright 2012 Megan A. Bledsoe 2 Bledsoe - DMA Harp Performance University of Washington Abstract The Harp in Jazz and American Pop Music Megan A. Bledsoe Chair of the Supervisory Committee: Assistant Professor of Flute Donna Shin, Chair Instrumental Performance, School of Music The harp has endured a tenuous relationship with the genres of jazz and American popular music throughout history. While a few harpists have enjoyed successful and significant careers in these fields, the harp is largely absent from mainstream jazz and American pop. The purpose of this dissertation is to ascertain a definitive cause for such exclusion and use this information to identify a feasible path toward further integration of the harp in jazz and American pop music. This paper examines the state of the harp in jazz and American pop from various angles, including historical perspective, analytical assessment, and a study which compares harpists’ improvisational abilities to those of their mainstream jazz instrumentalist counterparts. These evaluations yield an encompassing view of the harp’s specific advantages and detriments in the areas of jazz and American pop. The result of this research points to a need for specialization among harpists, particularly in defining new styles. It is evident that harpists’ careers generally necessitate a working knowledge of various styles of music. -

Willis Conover, the Voice of America, and the International Reception of Avant-Garde Jazz in the 1960S

“SOUNDS FOR ADVENTUROUS LISTENERS”: WILLIS CONOVER, THE VOICE OF AMERICA, AND THE INTERNATIONAL RECEPTION OF AVANT-GARDE JAZZ IN THE 1960S Mark A. Breckenridge, B.M., M.M., M.M.E. Dissertation Prepared for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY UNIVERSITY OF NORTH TEXAS August 2012 APPROVED: John P. Murphy, Major Professor and Interim Director of Graduate Studies in Music Eileen M. Hayes, Minor Professor and Chair of the Division of Music History, Theory, and Ethnomusicology Mark McKnight, Committee Member Ana Alonso-Minutti, Committee Member James C. Scott, Dean of the College of Music Mark Wardell, Dean of the Toulouse Graduate School Breckenridge, Mark A., “Sounds for Adventurous Listeners”: Willis Conover, the Voice of America, and the International Reception of Avant-garde Jazz in the 1960s. Doctor of Philosophy (Musicology), August 2012, 315 pp., 27 figures, bibliography, 189 titles. In “Sounds for Adventurous Listeners,” I argue that Conover’s role in the dissemination of jazz through the Music USA Jazz Hour was more influential on an educational level than what literature on Conover currently provides. Chapter 2 begins with an examination of current studies regarding the role of jazz in Cold War diplomacy, the sociopolitical implications of avant-garde jazz and race, the convergence of fandom and propaganda, the promoter as facilitator of musical trends, and the influence of international radio during the Cold War. In chapter 3 I introduce the Friends of Music USA Newsletter and explain its function as a record of overseas jazz reception and a document that cohered a global network of fans. I then focus on avant-garde debates of the 1960s and discuss Conover’s role overseas and in the United States. -

Film Music and Film Genre

Film Music and Film Genre Mark Brownrigg A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Stirling April 2003 FILM MUSIC AND FILM GENRE CONTENTS Page Abstract Acknowledgments 11 Chapter One: IntroductionIntroduction, Literature Review and Methodology 1 LiteratureFilm Review Music and Genre 3 MethodologyGenre and Film Music 15 10 Chapter Two: Film Music: Form and Function TheIntroduction Link with Romanticism 22 24 The Silent Film and Beyond 26 FilmTheConclusion Function Music of Film Form Music 3733 29 Chapter Three: IntroductionFilm Music and Film Genre 38 FilmProblems and of Genre Classification Theory 4341 FilmAltman Music and Genre and GenreTheory 4945 ConclusionOpening Titles and Generic Location 61 52 Chapter Four: IntroductionMusic and the Western 62 The Western and American Identity: the Influence of Aaron Copland 63 Folk Music, Religious Music and Popular Song 66 The SingingWest Cowboy, the Guitar and other Instruments 73 Evocative of the "Indian""Westering" Music 7977 CavalryNative and American Civil War WesternsMusic 84 86 PastoralDown andMexico Family Westerns Way 89 90 Chapter Four contd.: The Spaghetti Western 95 "Revisionist" Westerns 99 The "Post - Western" 103 "Modern-Day" Westerns 107 Impact on Films in other Genres 110 Conclusion 111 Chapter Five: Music and the Horror Film Introduction 112 Tonality/Atonality 115 An Assault on Pitch 118 Regular Use of Discord 119 Fragmentation 121 Chromaticism 122 The A voidance of Melody 123 Tessitura in extremis and Unorthodox Playing Techniques 124 Pedal Point -

Conncensus Vol. 48 No. 2

Connecticut College Digital Commons @ Connecticut College 1962-1963 Student Newspapers 9-27-1962 ConnCensus Vol. 48 No. 2 Connecticut College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.conncoll.edu/ccnews_1962_1963 Recommended Citation Connecticut College, "ConnCensus Vol. 48 No. 2" (1962). 1962-1963. 21. https://digitalcommons.conncoll.edu/ccnews_1962_1963/21 This Newspaper is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Newspapers at Digital Commons @ Connecticut College. It has been accepted for inclusion in 1962-1963 by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Connecticut College. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The views expressed in this paper are solely those of the author. Conn Ce s s Price 10 ents Vol. 48--No. 2 New London, Connecticut, Thursday, eptember 27, 1962 Library Currently Exhibit Alumnae Meet College Faculty Publication For Weekend ~urrently exhibited on the George Herbert, 1951, and Images mal.n floor of the library is a col- and Themes In Five poems by Of Talks, Tours lection of faculty publications. l\U1ton, 1957; The English DIe- These books and pamphlets pre- ttonarv from Oawdrey 1.0 Johnson 1VJo hundred alumna, their sent an impressive array both of 16M·17M by Miss Noyes; ThLl'it guests. and on hundred prcspec- publishing houses and university ot Norman NalllC8 [n the Auchkn- tlv college stud nts will visit the presses here and abroad and of look i\l . (Battle Abbey n.oll) by Connecticut College campus Sat- subject matter. The fields covered Mr. Smyser in 1'1001 val 't.1Jdl urday, Octob r 6. The alumnae, include English and foreign lan- in Honor ot J. -

ELECTRONIC MUSIC in FRANCE SURVEY 1369 SACEM ETUDEMUSIKELECTRO INT Eng.Qxp Mise En Page 1 17/01/2017 17:49 Page1

1369_SACEM_ETUDEMUSIKELECTRO_COUV_dos5_Eng.qxp_Mise en page 1 17/01/2017 17:48 Page1 ELECTRONIC MUSIC IN FRANCE SURVEY 1369_SACEM_ETUDEMUSIKELECTRO_INT_Eng.qxp_Mise en page 1 17/01/2017 17:49 Page1 ELECTRONIC MUSIC IN FRANCE SURVEY 1369_SACEM_ETUDEMUSIKELECTRO_INT_Eng.qxp_Mise en page 1 17/01/2017 17:49 Page2 introduction overview of the ecosystem economic impact 6 9 35 DEFINITION OVERVIEW OF THE ECONOMIC AND ARTISTIC, ECOSYSTEM IMPACT CULTURAL OF ELECTRONIC OF ELECTRONIC AND ECONOMIC MUSIC MUSIC HISTORY IN FRANCE IN FRANCE 12 40 CREATION FOCUS ON FESTIVALS 18 PRODUCTION 42 & PROMOTION FOCUS ON CLUBS 20 DISTRIBUTION 22 BROADCASTING 26 PUBLISHING 28 MANAGEMENT 32 AUDIENCE 2 1369_SACEM_ETUDEMUSIKELECTRO_INT_Eng.qxp_Mise en page 1 17/01/2017 17:49 Page3 development challenges conclusion appendix 45 62 64 DEVELOPMENT WORKING GROUP CHALLENGES FOR 67 ELECTRONIC ACKNOWLEDGEMENT MUSIC 46 ARTISTS 49 CHALLENGES FOR RIGHTS MANAGEMENT 56 CLUBS 58 FESTIVALS 60 SUSTAINABILITY OF CULTURAL STRUCTURES 3 1369_SACEM_ETUDEMUSIKELECTRO_INT_Eng.qxp_Mise en page 1 17/01/2017 17:49 Page4 1369_SACEM_ETUDEMUSIKELECTRO_INT_Eng.qxp_Mise en page 1 17/01/2017 17:49 Page5 introduction overview of the ecosystem economic impact development challenges conclusion appendix FRAMEWORK, CONTEXT AND OBJECTIVES OF THE SURVEY After 30 years in existence, it was deemed This working group, throughout their important to draw an up-to-date overview of research, maintained an intellectual what the electronic music sector represents conformity and rigour, regarding the in France, both economically and culturally. methodology and content, that proved For this purpose, one hundred and fifty very productive. stakeholders in this music scene have been interviewed, creating an open information census of its major economic drivers and BENJAMIN BRAUN enabling its true evaluation, as well as defining its main practices.