Solar Radiation on Mars: Stationary ...Photovoltaic Array

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Solar Engineering Basics

Solar Energy Fundamentals Course No: M04-018 Credit: 4 PDH Harlan H. Bengtson, PhD, P.E. Continuing Education and Development, Inc. 22 Stonewall Court Woodcliff Lake, NJ 07677 P: (877) 322-5800 [email protected] Solar Energy Fundamentals Harlan H. Bengtson, PhD, P.E. COURSE CONTENT 1. Introduction Solar energy travels from the sun to the earth in the form of electromagnetic radiation. In this course properties of electromagnetic radiation will be discussed and basic calculations for electromagnetic radiation will be described. Several solar position parameters will be discussed along with means of calculating values for them. The major methods by which solar radiation is converted into other useable forms of energy will be discussed briefly. Extraterrestrial solar radiation (that striking the earth’s outer atmosphere) will be discussed and means of estimating its value at a given location and time will be presented. Finally there will be a presentation of how to obtain values for the average monthly rate of solar radiation striking the surface of a typical solar collector, at a specified location in the United States for a given month. Numerous examples are included to illustrate the calculations and data retrieval methods presented. Image Credit: NOAA, Earth System Research Laboratory 1 • Be able to calculate wavelength if given frequency for specified electromagnetic radiation. • Be able to calculate frequency if given wavelength for specified electromagnetic radiation. • Know the meaning of absorbance, reflectance and transmittance as applied to a surface receiving electromagnetic radiation and be able to make calculations with those parameters. • Be able to obtain or calculate values for solar declination, solar hour angle, solar altitude angle, sunrise angle, and sunset angle. -

3.- the Geographic Position of a Celestial Body

Chapter 3 Copyright © 1997-2004 Henning Umland All Rights Reserved Geographic Position and Time Geographic terms In celestial navigation, the earth is regarded as a sphere. Although this is an approximation, the geometry of the sphere is applied successfully, and the errors caused by the flattening of the earth are usually negligible (chapter 9). A circle on the surface of the earth whose plane passes through the center of the earth is called a great circle . Thus, a great circle has the greatest possible diameter of all circles on the surface of the earth. Any circle on the surface of the earth whose plane does not pass through the earth's center is called a small circle . The equator is the only great circle whose plane is perpendicular to the polar axis , the axis of rotation. Further, the equator is the only parallel of latitude being a great circle. Any other parallel of latitude is a small circle whose plane is parallel to the plane of the equator. A meridian is a great circle going through the geographic poles , the points where the polar axis intersects the earth's surface. The upper branch of a meridian is the half from pole to pole passing through a given point, e. g., the observer's position. The lower branch is the opposite half. The Greenwich meridian , the meridian passing through the center of the transit instrument at the Royal Greenwich Observatory , was adopted as the prime meridian at the International Meridian Conference in 1884. Its upper branch is the reference for measuring longitudes (0°...+180° east and 0°...–180° west), its lower branch (180°) is the basis for the International Dateline (Fig. -

2 Coordinate Systems

2 Coordinate systems In order to find something one needs a system of coordinates. For determining the positions of the stars and planets where the distance to the object often is unknown it usually suffices to use two coordinates. On the other hand, since the Earth rotates around it’s own axis as well as around the Sun the positions of stars and planets is continually changing, and the measurment of when an object is in a certain place is as important as deciding where it is. Our first task is to decide on a coordinate system and the position of 1. The origin. E.g. one’s own location, the center of the Earth, the, the center of the Solar System, the Galaxy, etc. 2. The fundamental plan (x−y plane). This is often a plane of some physical significance such as the horizon, the equator, or the ecliptic. 3. Decide on the direction of the positive x-axis, also known as the “reference direction”. 4. And, finally, on a convention of signs of the y− and z− axes, i.e whether to use a left-handed or right-handed coordinate system. For example Eratosthenes of Cyrene (c. 276 BC c. 195 BC) was a Greek mathematician, elegiac poet, athlete, geographer, astronomer, and music theo- rist who invented a system of latitude and longitude. (According to Wikipedia he was also the first person to use the word geography and invented the disci- pline of geography as we understand it.). The origin of this coordinate system was the center of the Earth and the fundamental plane was the equator, which location Eratosthenes calculated relative to the parts of the Earth known to him. -

Celestial Coordinate Systems

Celestial Coordinate Systems Craig Lage Department of Physics, New York University, [email protected] January 6, 2014 1 Introduction This document reviews briefly some of the key ideas that you will need to understand in order to identify and locate objects in the sky. It is intended to serve as a reference document. 2 Angular Basics When we view objects in the sky, distance is difficult to determine, and generally we can only indicate their direction. For this reason, angles are critical in astronomy, and we use angular measures to locate objects and define the distance between objects. Angles are measured in a number of different ways in astronomy, and you need to become familiar with the different notations and comfortable converting between them. A basic angle is shown in Figure 1. θ Figure 1: A basic angle, θ. We review some angle basics. We normally use two primary measures of angles, degrees and radians. In astronomy, we also sometimes use time as a measure of angles, as we will discuss later. A radian is a dimensionless measure equal to the length of the circular arc enclosed by the angle divided by the radius of the circle. A full circle is thus equal to 2π radians. A degree is an arbitrary measure, where a full circle is defined to be equal to 360◦. When using degrees, we also have two different conventions, to divide one degree into decimal degrees, or alternatively to divide it into 60 minutes, each of which is divided into 60 seconds. These are also referred to as minutes of arc or seconds of arc so as not to confuse them with minutes of time and seconds of time. -

The Celestial Sphere

The Celestial Sphere Useful References: • Smart, “Text-Book on Spherical Astronomy” (or similar) • “Astronomical Almanac” and “Astronomical Almanac’s Explanatory Supplement” (always definitive) • Lang, “Astrophysical Formulae” (for quick reference) • Allen “Astrophysical Quantities” (for quick reference) • Karttunen, “Fundamental Astronomy” (e-book version accessible from Penn State at http://www.springerlink.com/content/j5658r/ Numbers to Keep in Mind • 4 π (180 / π)2 = 41,253 deg2 on the sky • ~ 23.5° = obliquity of the ecliptic • 17h 45m, -29° = coordinates of Galactic Center • 12h 51m, +27° = coordinates of North Galactic Pole • 18h, +66°33’ = coordinates of North Ecliptic Pole Spherical Astronomy Geocentrically speaking, the Earth sits inside a celestial sphere containing fixed stars. We are therefore driven towards equations based on spherical coordinates. Rules for Spherical Astronomy • The shortest distance between two points on a sphere is a great circle. • The length of a (great circle) arc is proportional to the angle created by the two radial vectors defining the points. • The great-circle arc length between two points on a sphere is given by cos a = (cos b cos c) + (sin b sin c cos A) where the small letters are angles, and the capital letters are the arcs. (This is the fundamental equation of spherical trigonometry.) • Two other spherical triangle relations which can be derived from the fundamental equation are sin A sinB = and sin a cos B = cos b sin c – sin b cos c cos A sina sinb € Proof of Fundamental Equation • O is -

The Solar Resource

CHAPTER 7 THE SOLAR RESOURCE To design and analyze solar systems, we need to know how much sunlight is available. A fairly straightforward, though complicated-looking, set of equations can be used to predict where the sun is in the sky at any time of day for any location on earth, as well as the solar intensity (or insolation: incident solar Radiation) on a clear day. To determine average daily insolation under the com- bination of clear and cloudy conditions that exist at any site we need to start with long-term measurements of sunlight hitting a horizontal surface. Another set of equations can then be used to estimate the insolation on collector surfaces that are not flat on the ground. 7.1 THE SOLAR SPECTRUM The source of insolation is, of course, the sun—that gigantic, 1.4 million kilo- meter diameter, thermonuclear furnace fusing hydrogen atoms into helium. The resulting loss of mass is converted into about 3.8 × 1020 MW of electromagnetic energy that radiates outward from the surface into space. Every object emits radiant energy in an amount that is a function of its tem- perature. The usual way to describe how much radiation an object emits is to compare it to a theoretical abstraction called a blackbody. A blackbody is defined to be a perfect emitter as well as a perfect absorber. As a perfect emitter, it radiates more energy per unit of surface area than any real object at the same temperature. As a perfect absorber, it absorbs all radiation that impinges upon it; that is, none Renewable and Efficient Electric Power Systems. -

Local Sidereal Time (LST) = Greenwich Sidereal Time (GST) +

AST326, 2010 Winter Semester • Celestial Sphere • Spectroscopy • (Something interesting; e.g ., advanced data analyses with IDL) • Practical Assignment: analyses of Keck spectroscopic data from the instructor (can potentially be a research paper) − “there will be multiple presentations by students” • Telescope sessions for spectroscopy in late Feb &March • Bonus projects (e.g., spectroscopic observations using the campus telescope) will be given. Grading: Four Problem Sets (16%), Four Lab Assignments (16%), Telescope Operation – Spectrograph (pass or fail; 5%), One Exam(25%), Practical Assignment (28%), Class Participation & Activities (10%) The Celestial Sphere Reference Reading: Observational Astronomy Chapter 4 The Celestial Sphere We will learn ● Great Circles; ● Coordinate Systems; ● Hour Angle and Sidereal Time, etc; ● Seasons and Sun Motions; ● The Celestial Sphere “We will be able to calculate when a given star will appear in my sky.” The Celestial Sphere Woodcut image displayed in Flammarion's `L'Atmosphere: Meteorologie Populaire (Paris, 1888)' Courtesy University of Oklahoma History of Science Collections The celestial sphere: great circle The Celestial Sphere: Great Circle A great circle on a sphere is any circle that shares the same center point as the sphere itself. Any two points on the surface of a sphere, if not exactly opposite one another, define a unique great circle going through them. A line drawn along a great circle is actually the shortest distance between the two points (see next slides). A small circle is any circle drawn on the sphere that does not share the same center as the sphere. The celestial sphere: great circle The Celestial Sphere: Great Circle •A great circle divides the surface of a sphere in two equal parts. -

Using the SFA Star Charts and Understanding the Equatorial Coordinate System

Using the SFA Star Charts and Understanding the Equatorial Coordinate System SFA Star Charts created by Dan Bruton of Stephen F. Austin State University Notes written by Don Carona of Texas A&M University Last Updated: August 17, 2020 The SFA Star Charts are four separate charts. Chart 1 is for the north celestial region and chart 4 is for the south celestial region. These notes refer to the equatorial charts, which are charts 2 & 3 combined to form one long chart. The star charts are based on the Equatorial Coordinate System, which consists of right ascension (RA), declination (DEC) and hour angle (HA). From the northern hemisphere, the equatorial charts can be used when facing south, east or west. At the bottom of the chart, you’ll notice a series of twenty-four numbers followed by the letter “h”, representing “hours”. These hour marks are right ascension (RA), which is the equivalent of celestial longitude. The same point on the 360 degree celestial sphere passes overhead every 24 hours, making each hour of right ascension equal to 1/24th of a circle, or 15 degrees. Each degree of sky, therefore, moves past a stationary point in four minutes. Each hour of right ascension moves past a stationary point in one hour. Every tick mark between the hour marks on the equatorial charts is equal to 5 minutes. Right ascension is noted in ( h ) hours, ( m ) minutes, and ( s ) seconds. The bright star, Antares, in the constellation Scorpius. is located at RA 16h 29m 30s. At the left and right edges of the chart, you will find numbers marked in degrees (°) and being either positive (+) or negative(-). -

NOAA Technical Memorandum ERL ARL-94

NOAA Technical Memorandum ERL ARL-94 THE NOAA SOLAR EPHEMERIS PROGRAM Albion D. Taylor Air Resources Laboratories Silver Spring, Maryland January 1981 NOAA 'Technical Memorandum ERL ARL-94 THE NOAA SOLAR EPHEMERlS PROGRAM Albion D. Taylor Air Resources Laboratories Silver Spring, Maryland January 1981 NOTICE The Environmental Research Laboratories do not approve, recommend, or endorse any proprietary product or proprietary material mentioned in this publication. No reference shall be made to the Environmental Research Laboratories or to this publication furnished by the Environmental Research Laboratories in any advertising or sales promotion which would indicate or imply that the Environmental Research Laboratories approve, recommend, or endorse any proprietary product or proprietary material mentioned herein, or which has as its purpose an intent to cause directly or indirectly the advertised product to be used or purchased because of this Environmental Research Laboratories publication. Abstract A system of FORTRAN language computer programs is presented which have the ability to locate the sun at arbitrary times. On demand, the programs will return the distance and direction to the sun, either as seen by an observer at an arbitrary location on the Earth, or in a stan- dard astronomic coordinate system. For one century before or after the year 1960, the program is expected to have an accuracy of 30 seconds 5 of arc (2 seconds of time) in angular position, and 7 10 A.U. in distance. A non-standard algorithm is used which minimizes the number of trigonometric evaluations involved in the computations. 1 The NOAA Solar Ephemeris Program Albion D. Taylor National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration Air Resources Laboratories Silver Spring, MD January 1981 Contents 1 Introduction 3 2 Use of the Solar Ephemeris Subroutines 3 3 Astronomical Terminology and Coordinate Systems 5 4 Computation Methods for the NOAA Solar Ephemeris 11 5 References 16 A Program Listings 17 A.1 SOLEFM . -

Astrocalc4r: Software to Calculate Solar Zenith Angle

Northeast Fisheries Science Center Reference Document 11-14 AstroCalc4R: Software to Calculate Solar Zenith Angle; Time at sunrise, Local Noon, and Sunset; and Photosynthetically Available Radiation Based on Date, Time, and Location by Larry Jacobson, Alan Seaver, and Jiashen Tang August 2011 Recent Issues in This Series 10-15 Bluefish 2010 Stock Assessment Update, by GR Shepherd and J Nieland. July 2010. 10-16 Stock Assessment of Scup for 2010, by M Terceiro. July 2010. 10-17 50th Northeast Regional Stock Assessment Workshop (50th SAW) Assessment Report, by Northeast Fisheries Science Center. August 2010. 10-18 An Updated Spatial Pattern Analysis for the Gulf of Maine-Georges Bank Atlantic Herring Complex During 1963-2009, by JJ Deroba. August 2010. 10-19 International Workshop on Bioextractive Technologies for Nutrient Remediation Summary Report, by JM Rose, M Tedesco, GH Wikfors, C Yarish. August 2010. 10-20 Northeast Fisheries Science Center publications, reports, abstracts, and web documents for calendar year 2009, by A Toran. September 2010. 10-21 12th Flatfish Biology Conference 2010 Program and Abstracts, by Conference Steering Committee. October 2010. 10-22 Update on Harbor Porpoise Take Reduction Plan Monitoring Initiatives: Compliance and Consequential Bycatch Rates from June 2008 through May 2009, by CD Orphanides. November 2010. 11-01 51st Northeast Regional Stock Assessment Workshop (51st SAW): Assessment Summary Report, by Northeast Fisheries Science Center. January 2011. 11-02 51st Northeast Regional Stock Assessment Workshop (51st SAW): Assessment Report, by Northeast Fisheries Science Center. March 2011. 11-03 Preliminary Summer 2010 Regional Abundance Estimate of Loggerhead Turtles (Caretta caretta) in Northwestern Atlantic Ocean Continental Shelf Waters, by the Northeast Fisheries Science Center and the Southeast Fisheries Science Center. -

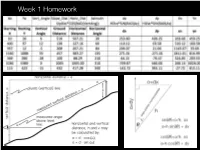

Week 1 Homework You Can Only Use a Planar Surface So Far, Before the Equidistance Assumption Creates Large Errors

Week 1 Homework You can only use a planar surface so far, before the equidistance assumption creates large errors Distance error from Kiester to Warroad is greater than two football fields in length Longitudes are great circles, latitudes are small circles (except the Equator, which is a GC) Spherical Geometry Longitude Spherical Geometry Note: The Greek letter l (lambda) is almost always used to specify longitude while f, a, w and c, and other symbols are used to specify latitude Great and Small Circles Great circles splits the Small circles splits the earth into equal halves earth into unequal halves wikipedia geography.name All lines of equal longitude are great circles Equator is the only line of equal latitude that’s a great circle 90 deg Equator to Poles Surface distance measurements should all be along a great circle Caliper Corporation Note that great circle distances appear curved on projected or flat maps Smithsonian In GIS Fundamentals book, Chapter 2 Latitude - angle to a parallel circle, a small circle parallel to the Equatorial great circle Spherical Geometry Three measures: Latitude, Longitude, and Earth Radius + height above/ below the sphere (hp) How do we measure latitude/longitude? Well, now, GNSS, but originally, astronomic measurements: latitude by north star or solar noon angles, at equinox Longitude Measurement Method 1: The Earth rotates 360 degrees in a day, or 15 degrees per hour. If we know the time difference between 2 points, and the longitude of the first point (Greenwich), we can determine the longitude at our current location. Method 2: Create a table of moon-star distances for each day/time of the year at a reference location (Greenwich observatory) Measure the same moon-star distance somewhere else at a standard or known time. -

Calculate and Analysis of Air Mass and Solar Angles of Mosul City

------ Raf. J. Sci., Vol. 27, No.4, pp.57-65, 2018------ Calculate and Analysis of Air Mass and Solar Angles of Mosul City Taha M. Al-Maula Abdullah I. Al-Abdulla Department of Physics/ College of Science/ University of Mosul E-mail: [email protected] E-mail: [email protected]. (Received 16 / 4/ 2018 ; Accepted 12 / 6 / 2018 ) ABSTRACT The solar radiation energy of the city of Mosul was calculated according to the value of AM = 1.24 on 21 March and September, theoretically using formula 7 and measuring it practically using the radiometer of the intensity of the optical radiation emitted from the solar simulator that was designed in the laboratory. There are values of 982 W / m2 and 996 W / m2 , respectively, comparing these values in Table 1 with published values for other sites. Table (1) AM values and solar radiation intensity theoretically using formula (7) and practically for different angular values. For the purpose of solar simulators manufacturing, the air mass (AM) were calculated for the city of Mosul at Altitude line (36.35o) and Longitude line (43.100) and at a height of 220 meters above sea level, this required the computation of the Solar inclination angle (δ), the hour angle ( , the Solar elevation angle (h) and the zenith angle (Z), in addition to that, the calculations were studied in specified day, chosen at the 21st of each month From sunrise to sunset, which is the daylight hours. The study showed that, the values of AM become equals to one at twelve o'clock and 1.24 on the 21st of March and September when the sun at the zenith angle 36.35o.