Download Working Paper No

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pathway to Zero Emissions CHE at the Port of Oakland

Pathway to Zero Emissions CHE at the Port of Oakland Diane Heinze Environmental Supervisor Advanced Clean CHE: End-User Case Studies 8:30 a.m. D. Heinze Port of Oakland ACT Expo April 26, 2019 1 580 Some items not toscale MAGNETIC 14°11' 0 1/2 1 nautical mile BuildingLegend OCEAN CARRIER BY TERMINAL 0 1/2 1 mile 1 Impact Transportation (Buildings 807, 806,805) 0 1 kilometer 80 2 Port Transfer (Building804) TRAPACTERMINAL COSCO SHIPPING Lines 3 PCC Logistics (Building 803) - Customs Exam Station EBMUD Evergreen Line TerminalGates 4 Planned Site of port drayage truck Hapag - Lloyd fuel & service center Container Cranes (Port Owned) Ocean Network Express (ONE) 5 Port Truck CSC & Sea-Logix - 1425 MaritimeSt. * Yang Ming Line Container Cranes (TenantOwned) Toll Plaza City Truck Parking& (westboundonly) AncillaryServices 6 Shippers TransportExpress Cranes(Private) Northport 14 OverweightCorridor Beach 7 PacificTransload BEN E. NUTTERTERMINAL City OAB Area 8 GSCLogistics American President Lines (APL) PortScales AMNAVMaritime Tug Services 9 Unicold CMA CGM Shore PowerCapable 13 1 COSCO SHIPPING Lines 10 U.S. Customs and Border Protection 1 Evergreen Line A AdminBuildings Dredge * Materials 1 11 Port Harbor Facilities - 651 MaritimeSt. Rehandling 4 R RFID ServiceCenter Facility 12 Pacific LayberthingSouth 2 City OAB Area 13 ITS ConGlobal - WestBurma 12 R 3 OAKLAND INTERNATIONAL 14 OMSS CONTAINERTERMINAL 5 Port Truck Parking American President Lines (APL) & Ancillary Services * * ANL * CMA CGM 24 COSCO SHIPPING Lines Oakland * Evergreen Line Hamburg Süd B20-24 CenterPoint e Properties . * Hapag-Lloyd 1599 MaritimeSt. y w . * Hyundai Merchant Marine delin t (Available) t 980 Mandela Pk Union S S A * Maersk Line Turning * Mediterranean Shipping Company (MSC) STE * Ocean Network Express (ONE) 880 1,650 ft / 502.9 m * Orient Overseas Container Line (OOCL) 1/2 6 7 8thSt. -

Seaport Facilities

SEAPORT FACILITIES 580 Some items not to scale MAGNETIC N 14° 11' 0 1/2 1 nautical mile Building Legend OCEAN CARRIER BY TERMINAL E 0 1/2 1 mile 1 Impact Transportation (Buildings 807, 806, 805) W 0 1/2 1 kilometer 80 2 Port Transfer (Building 804) TRAPAC TERMINAL S COSCO SHIPPING Lines 3 PCC Logistics (Building 803) - Customs Exam Station EBMUD Evergreen Line Terminal Gates 4 Planned Site of port drayage truck Hapag - Lloyd fuel & service center Container Cranes (Port Owned) Ocean Network Express (ONE) 5 Port Truck CSC & Sea-Logix - 1425 Maritime St. * Yang Ming Line Container Cranes (Tenant Owned) Toll Plaza City Truck Parking & (westbound only) Ancillary Services 6 Shippers Transport Express Cranes (Private) Northport 14 7 Overweight Corridor Beach Pacific Transload BEN E. NUTTER TERMINAL City OAB Area rologis 1 P 8 GSC Logistics West Grand A American President Lines (APL) Port Scales AMNAV Maritime v. Tug Services 9 Unicold CMA CGM 13 1 Shore Power Capable . rologis 3 9 P 10 COSCO SHIPPING Lines urma Rd U.S. Customs and Border Protection 8 ologis 2 1 West B 10 Dredge r Evergreen Line A Admin Buildings P 11 Materials 1 Port Harbor Facilities - 651 Maritime St. * Rehandling Facility 4 R RFID Service Center St. 12 Pacific Layberthing South 17th 2 City OAB Area 21 20 . 13 ITS ConGlobal - West Burma 12 3 d 7 22 R OAKLAND INTERNATIONAL 14 ridge tage R OMSS n CONTAINER TERMINAL X439 y B ro a F S 5 Pinnacle an Port Truck Parking P American President Lines (APL) Oakland B 14th St. -

Federal Register/Vol. 69, No. 72/Wednesday, April 14, 2004/Notices

19852 Federal Register / Vol. 69, No. 72 / Wednesday, April 14, 2004 / Notices whether the proposed collection of paperwork implications. These are DC offices of the Commission, 800 information is necessary for the proper foreign ownership, substantial service, North Capitol Street, NW., Room 940. performance of the functions of the and interference coordination. The Interested parties may submit comments Commission, including whether the foreign ownership and interference on an agreement to the Secretary, information shall have practical utility; requirements are only a one-time Federal Maritime Commission, (b) the accuracy of the Commission’s requirement unless the licensee’s Washington, DC 20573, within 10 days burden estimate; (c) ways to enhance ownership changes or they change the of the date this notice appears in the the quality, utility and clarity of the service or equipment they are using. Federal Register. information collected; and (d) ways to The substantial service requirement Agreement No.: 011574–010. minimize the burden of the collection of would have to be made at the end of a Title: Pacific Islands Discussion information on the respondents, licensee’s license term. Agreement. including the use of automated Federal Communications Commission. Parties: P & O Nedlloyd Limited, Hamburg-Su¨ d, Polynesia Line Ltd., collection techniques or other forms of Marlene H. Dortch, information technology. FESCO Ocean Management Limited, Secretary. DATES: and Australia-New Zealand Direct Line. Written Paperwork Reduction [FR Doc. 04–8486 Filed 4–13–04; 8:45 am] (PRA) comments should be submitted Synopsis: The amendment revises the BILLING CODE 6712–01–P on or before June 14, 2004. -

Federal Register/Vol. 83, No. 3/Thursday, January

528 Federal Register / Vol. 83, No. 3 / Thursday, January 4, 2018 / Notices CONTACT PERSON FOR MORE INFORMATION: Wallenius Wilhelmsen Logistics; and Street NW, #300, Washington, DC Judith Ingram, Press Officer, Telephone: ZIM Integrated Shipping Services Ltd. 20036, [email protected], and Joshua (202) 694–1220. Filing Party: Wayne R. Rohde, Esq.; P. Stein, Cozen O’ Connor, 1200 19th Cozen O’Conner; 1200 Nineteenth Street Street NW, #300, Washington, DC Laura E. Sinram, NW; Washington, DC 20036. 20036, [email protected]. Deputy Secretary of the Commission. Synopsis: The amendment deletes Non-confidential filings may be [FR Doc. 2018–00057 Filed 1–2–18; 4:15 pm] Kawasaki Kisen Kaisha, Ltd. as a party submitted in hard copy to the Secretary BILLING CODE 6715–01–P to the Agreement. at the above address or by email as a By Order of the Federal Maritime PDF attachment to [email protected] Commission. and include in the subject line: P5–17 FEDERAL MARITIME COMMISSION Dated: December 29, 2017. (Commenter/Company). Confidential Rachel E. Dickon, filings should not be filed by email. A Notice of Agreements Filed confidential filing must be filed with the Assistant Secretary. The Commission hereby gives notice Secretary in hard copy only, and be [FR Doc. 2017–28485 Filed 1–3–18; 8:45 am] accompanied by a transmittal letter that of the filing of the following agreements BILLING CODE 6731–AA–P under the Shipping Act of 1984. identifies the filing as ‘‘Confidential- Interested parties may submit comments Restricted’’ and describes the nature and on the agreements to the Secretary, FEDERAL MARITIME COMMISSION extent of the confidential treatment Federal Maritime Commission, requested. -

Carrier Name SCAC Code ACL ACLU Alianca ANRM AML AKMR ANL ANNU APL APLU Arkas ARKU ARRC AROF Bahri NS

Carrier Name (Abbreviated) Carrier Name SCAC code ACL Atlantic Container Line ACLU Alianca Alianca ANRM AML Alaska Marine Lines AKMR ANL Australia National Line ANNU APL American President Lines APLU Arkas Arkas Container Transport S.A. ARKU ARRC Atlantic Ro-Ro Carriers Inc AROF Bahri Bahri / National Shipping Company of Saudi Arabia NSAU BCL Bermuda Container Line BCLU CGL Central Gulf Lines, Inc CEGL CCNI Compagnia Chilena de Navigacion Interoceanica SA CNIU CHIPOLBROK Chinese-Polish Joint Stock Shipping Company CPJQ CK Line CK Line CKLU Compagnie Maritime d Affretement Compagnie Generale CMA CGM Maritime CMDU CNC Line Cheng Lie Navigation Co.,Ltd 11DX COSCO COSCO Container Lines COSU Crowley Crowley CMCU/CAMN CSAV Compania Sud Americana de Vapores CHIW CSAV Norasia CSAV Norasia NSLU CSCL China Shipping Container Lines Co CHNJ Delmas Delmas DAAE Dole Dole Ocean Cargo Express DOLQ Ecuadorian Line Ecuadorian Line EQLI Eimskip Eimskip EIMU/EIMW Emirates Emirates Shipping Line ESPU Eukor Eukor EUKO Evergreen Evergreen Line EGLV FESCO Far Eastern Shipping Company FESO GAL Galborg GFAL Grieg Star Grieg Star Shipping ACSU Grimaldi Grimaldi GRIU GSL Gold Star Line Ltd. GSLU GWF Great White Fleet UBCU GES Great Eastern Shipping Inc. GESC HAMBURG SUD Hamburg Sud SUDU Hanjin Hanjin Shipping Co. Ltd. HJSC Hapag Lloyd Hapag Lloyd Container Line/A> HLCU HMM Hyundai Merchant Marine Co., Ltd. HDMU Hoegh Hoegh Autoliners HUAU Horizon Horizon Lines HRZU Hyde Shipping Hyde Shipping HYDU ICL Independent Container Line IILU IMC Industrial Maritime Carriers (Intermarine) IDMC Interocean Lines Interocean Lines INOC K Line Kawasaki Kisen Kaisha, Ltd. KKLU King Ocean King Ocean Sercies KOSL KMTC Korea Marine Transport Co., Ltd. -

Transpacific Services in Oakland

Transpacific Services in Oakland THE Alliance Hapag-Lloyd, K-Line, MOL, NYK, Yang Ming Ocean Carrier Service Name Terminal Rotation 1 APL JPX CMA-CGM FUJI Hapag–Lloyd K Line Kobe–Nagoya–Tokyo–Sendai–San Pedro Bay– PS1 OICT MOL Oakland–Tokyo–Nagoya–Kobe–Sendai NYK 2 COSCO Shipping PSW3 K Line MOL Kobe–Nagoya–Shimizu–Tokyo–San Pedro Bay– PS2 TRAPAC NYK Oakland–Tokyo–Kobe–Nagoya–Shimizu Yang Ming 3 Hapag–Lloyd K Line Singapore–Laem Chabang–Cai Mep–Hong Kong– MOL PS3 TRAPAC San Pedro Bay–Oakland–Tokyo–Hong Kong– NYK Singapore–Laem Chabang–Cai Mep Yang Ming 4 Hapag–Lloyd K Line Hong Kong–Yantian–Kaohsiung–Keelung– MOL PS4 OICT San Pedro Bay–Oakland–Keelung–Kaohsiung– NYK Da Chan Bay/Shenzen–Hong Kong–Yantian Yang Ming 5 Hapag–Lloyd K Line MOL PS5 OICT Shanghai–Ningbo–San Pedro Bay–Oakland NYK Yang Ming 6 Hapag–Lloyd K Line Qingdao–Ningbo–Shanghai–Busan–San Pedro Bay– MOL PS6 TRAPAC NYK Oakland–Busan–Qingdao–Ningbo–Shanghai Yang Ming 7 K Line Dalian–Xingang–Qingdao–Busan–San Pedro Bay– MOL PS8 TRAPAC Oakland–Busan–Kwangyang–Dalian–Xingang– NYK Yang Ming Qingdao 8 Hapag–Lloyd K Line Tokyo–Kobe–Ningbo–Shanghai–Busan– MOL EC1 WB TRAPAC NYK San Pedro Bay–Oakland Yang Ming 2M Maersk, MSC Ocean Carrier Service Name Terminal Rotation 1 Maersk TP8 Xingang–Qingdao–Ningbo–Busan–Yokohama– OICT MSC ORIENT San Pedro Bay–Oakland–Vostochny–Xingang 2 Maersk TP2 Tanjung Pelepas–Cai Mep–Yantian–Shanghai– MSC JAGUAR OICT San Pedro Bay–Oakland–Vostochny–Busan– Shanghai–Ningbo–Chiwan–Singapore Bolded Carrier(s) operates the majority of vessel within the service route. -

Ocean Carrier Services

Ocean Carrier Services - Port of Oakland Transpacific Services THE Alliance Hapag-Lloyd, ONE, Yang Ming OCEAN CARRIER SERVICE NAME TERMINAL VESSEL SIZE ROTATION 1 ONE (5 vessels) FP1 Hapag-Lloyd CMA CGM(ⱡ) FUJI 4,888 - Singapore(ⱡ)–Kobe–Nagoya–Tokyo–San Pedro Bay– APL(ⱡ) JPX TRAPAC 4,992 Oakland–Tokyo–Shimizu(ⱡ)–Kobe–Nagoya– OOCL(ⱡ) JPX Evergreen(ⱡ) PS1 2 ONE Singapore–Laem Chabang–Vung Tau/Cai Mep–Hong Hapag–Lloyd Kong–Yantian–San Pedro Bay– Yang Ming FP2 TRAPAC TBA Oakland–Yokohama–Hong Kong–Laem Chabang–Vung Tau/Cai Mep– 3 Yang Ming ONE 8,070 - Hong Kong–Yantian–Kaohsiung–Keelung– PS4 TRAPAC Hapag-Lloyd 8,620 San Pedro Bay–Oakland–Keelung–Kaohsiung– 4 ONE Hapag-Lloyd 3,700 - Qingdao–Shanghai–Ningbo–San Pedro PS6 OICT Yang Ming 8,210 Bay–Oakland–Tokyo– 5 ONE Xiamen–Hong Kong–Yantian–San Pedro Hapag-Lloyd PS7 TRAPAC 10,000 Bay–Oakland–Kobe– Yang Ming 6 ONE Shanghai–Kwangyang–Pusan–San Pedro Hapag-Lloyd PS8 TRAPAC TBA Bay–Oakland–Pusan–Kwangyang–Incheon Yang Ming 2M Maersk, MSC OCEAN CARRIER SERVICE NAME TERMINAL VESSEL SIZE ROTATION 1 Maersk TP8 Tianjin/Xingang–Qingdao–Shanghai–Busan– MSC(ⱡ) ORIENT 11,000 - OICT Yokohama–Prince Rupert–San Pedro 11,300 Hyundai(ⱡ) PS4 Bay–Oakland–Vostochniy(ⱡ) Hamburg Sud(ⱡ) UPAS 1 2 Maersk TP2 MSC (ⱡ) JAGUAR Singapore–Cai Mep–Yantian–Ningbo–Shanghai–San Hyundai (ⱡ) PS3 11,075 - OICT Pedro Bay–Oakland–Vostochniy(ⱡ)–Busan– Hamburg Sud (ⱡ) 13,800 Shanghai–Ningbo–Chiwan/Shekou–Singapore. UPAS 2 Bolded Carrier(s) operates all or the majority of vessels within the service (Italicized Carrier) denotes non-alliance -

Federal Register/Vol. 71, No. 148/Wednesday, August

Federal Register / Vol. 71, No. 148 / Wednesday, August 2, 2006 / Notices 43769 SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION: This is a telecommunications equipment Title: United States/Australasia summary of the Commission’s manufacturers and service providers to Discussion Agreement. document, DA 06–1485, released July ensure that their products are accessible Parties: A.P. Moller-Maersk A/S and 21, 2006. This designation or updated and usable to persons with disabilities, Safmarine Container Lines NV; ANL designation information may be sent to when readily achievable to do so. (See Singapore Pte Ltd.; Australia-New the Commission via e-mail to Implementation of sections 255 and Zealand Direct Line; CMA–CGM, S.A.; [email protected]. Contact 251(a)(2) of the Communications Act of Compagnie Maritime Marfret S.A.; CP information for section 255 1934, as enacted by the Ships USA, LLC; Hamburg-Su¨ d; Hapag- telecommunications equipment Telecommunications Act of 1996, Lloyd AG; and Wallenius Wilhelmsen manufacturers is posted on the Report and Order and Further Notice of Logistics AS. Consumer & Governmental Affairs Inquiry (RO and FNOI), WT Docket No. Filing Party: Wayne R. Rohde, Esq.; Bureau’s Web site at: http:// 96–198, FCC 99–181, 16 FCC Rcd 6417 Sher & Blackwell LLP; 1850 M Street, www.fcc.gov/cgb/dro/ (September 29, 1999), published at 65 NW; Suite 900; Washington, DC 20036. section255_manu.html; contact FR 63235, November 19, 1999). The Synopsis: The amendment reflects information for telecommunications regulations require, in part, that Hapag-Lloyd’s new corporate name. service providers is posted at: http:// equipment manufacturers and service Agreement No.: 011223–034. -

FEDERAL MARITIME COMMISSION Notice of Agreements Filed

This document is scheduled to be published in the Federal Register on 06/22/2016 and available online at http://federalregister.gov/a/2016-14814, and on FDsys.gov FEDERAL MARITIME COMMISSION Notice of Agreements Filed The Commission hereby gives notice of the filing of the following agreements under the Shipping Act of 1984. Interested parties may submit comments on the agreements to the Secretary, Federal Maritime Commission, Washington, DC 20573, within twelve days of the date this notice appears in the Federal Register. Copies of the agreements are available through the Commission’s website (www.fmc.gov) or by contacting the Office of Agreements at (202)- 523-5793 or [email protected]. Agreement No.: 011426-061. Title: West Coast of South America Discussion Agreement. Parties: CMA CGM S.A.; Hamburg-Süd; Hapg-Lloyd AG; Mediterranean Shipping Company, SA; and Seaboard Marine Ltd. Filing Party: Wayne R. Rohde, Esq.; Cozen O’Conner; 1200 Nineteenth Street NW; Washington, DC 20036. Synopsis: The amendment would add King Ocean Services Limited, Inc. as a party to the agreement. Agreement No.: 011574-019. Title: Pacific Islands Discussion Agreement. Parties: Hamburg Sud KG doing business under its own name and the name Fesco Australia/New Zealand Liner Services (FANZL); and Polynesia Line Ltd. Filing Party: Wayne R. Rohde, Esq.; Cozen O’Conner; 1200 Nineteenth Street NW; Washington, DC 20036. Synopsis: The amendment deletes CMA-CGM SA and Compagnie Maritime Marfret SA as parties to the agreement. Agreement No.: 012243-001. Title: MOL/Glovis Space Charter Agreement. Parties: Mitsui O.S.K. Lines, Ltd. and Hyundai Glovis Co., Ltd. -

FEDERAL MARITIME COMMISSION Notice of Agreements Filed

This document is scheduled to be published in the Federal Register on 11/23/2016 and available online at https://federalregister.gov/d/2016-28241, and on FDsys.gov FEDERAL MARITIME COMMISSION Notice of Agreements Filed The Commission hereby gives notice of the filing of the following agreements under the Shipping Act of 1984. Interested parties may submit comments on the agreements to the Secretary, Federal Maritime Commission, Washington, DC 20573, within twelve days of the date this notice appears in the Federal Register. Copies of the agreements are available through the Commission’s website (www.fmc.gov) or by contacting the Office of Agreements at (202)- 523-5793 or [email protected]. Agreement No.: 011117-057. Title: United States/Australasia Discussion Agreement. Parties: ANL Singapore Pte Ltd.; CMA-CGM.; Hamburg-Süd; Mediterranean Shipping Company S.A.; and Pacific International Lines (PTE) LTD. Filing Party: Wayne R. Rohde, Esq.; Cozen O’Connor; 1200 Nineteenth Street, NW; Washington, DC 20036. Synopsis: The amendment would add Compagnie Maritime Marfret S.A. as a party to the Agreement. Agreement No.: 011574-020. Title: Pacific Islands Discussion Agreement. Parties: Hamburg Sudamerikanische Dampfschifffahrts-Gesellschaft KG doing business under its own name and the name Fesco Australia/New Zealand Liner Services (FANZL); and Polynesia Line Ltd. Filing Party: Wayne R. Rohde, Esq.; Cozen O’Conner; 1200 Nineteenth Street NW; Washington, DC 20036. Synopsis: The amendment would add Compagnie Maritime Marfret S.A. as a party to the Agreement. Agreement No.: 011223-054. Title: Transpacific Stabilization Agreement. Parties: American President Lines, Ltd. and APL Co. PTE Ltd.; (operating as a single carrier); Maersk Line A/S; CMA CGM, S.A.; COSCO Container Lines Company Ltd; Evergreen Line Joint Service Agreement; Hanjin Shipping Co., Ltd.; Hapag-Lloyd AG; Hyundai Merchant Marine Co., Ltd.; Mediterranean Shipping Company; Orient Overseas Container Line Limited; Yangming Marine Transport Corp.; and Zim Integrated Shipping Services, Ltd. -

Concept Note 17 Ver 16

16th of August 2018 (Concept note #17) Making a fragmented and inefficient container industry more profitable through PortCDM by Mikael Lind, 1, 2 Michele Sancricca, 3 Andy Lane, 4 Michael Bergmann, 1 Robert Ward, 1 Richard T. Watson,1, 5 Niels Bjorn-Andersen,1 Sandra Haraldson, 1 Trond Andersen, 6 Phil Ballou 7 1RISE Viktoria, Sweden, 2Chalmers University of Technology, Sweden, 3Mediterranean Shipping Company, USA, 4CTI Consultancy, Singapore, 5University of Georgia, USA, 6Port of Stavanger, Norway, 7Society of Naval Architects and Marine Engineers, USA Introduction Japanese automakers Toyota and Honda are renowned for their relentless focus on cost reduction through first class optimization of their supply chains. In August 2018, they are reporting improving profits while US automakers are issuing profit warnings. 1 Toyota and Honda have successfully connected operational databases from the supporting business eco-systems in such a way that databases can be analysed intensively (AI, Business Analytics, etc.) to identify cost saving opportunities utilizing the Japanese kaizen philosophy for continuous improvement. They have learned that data-driven enterprises are more successful. In contrast, the self-organizing and fragmented nature of the maritime industry has traditionally deprived all actors of the data needed to achieve high levels of efficiency. Fragmentation is toxic to efficiency, but now we have an antidote - digital data sharing. The maritime segment of the container industry is very mature, but it is low-profit, fragmented and too many operations are not optimally synchronized. However, the adoption of the principles of Port Collaborative Decision Making (PortCDM) as an enabler of the Sea Traffic Management (STM) concept for shipping companies (within or outside alliances), ports, and terminals could substantially reduce the overall costs. -

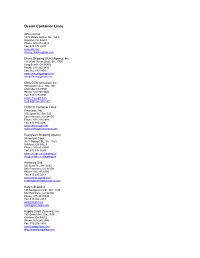

Ocean Container Lines

Ocean Container Lines APL Limited 1579 Middle Harbor Rd., 3rd Fl. Oakland, CA 94607 Phone: 510 272 2010 Fax: 510 272 2888 www.apl.com [email protected] China Shipping (N.A.) Agency, Inc. 111 West Ocean Blvd., Ste. 1700 Long Beach, CA 90802 Phone: 510 922 9456 Fax: 562 590 3801 www.chinashippingna.net [email protected] CMA CGM (America) Inc. 980 Atlantic Ave., Ste. 105 Alameda, CA 94501 Phone: 510 748 9200 Fax: 510 748 9800 www.cma-cgm.com [email protected] COSCO Container Lines Americas, Inc. 100 Spear St., Ste. 525 San Francisco, CA 94105 Phone: 415 778 7888 Fax: 415 882 9286 www.cosco-usa.com [email protected] Evergreen Shipping Agency (America) Corp. 7677 Oakport St., Ste. 1160 Oakland, CA 94621 Phone: 510 633 5080 Fax: 510 633 5085 www.evergreen-shipping.us [email protected] Hamburg Süd 333 Bush St., Ste. 2580 San Francisco, CA 94104 Phone: 415 495 6300 Fax: 415 495 2413 www.hamburgsud.com [email protected] Hanjin Shipping 180 Montgomery St., Ste. 1938 San Francisco, CA 94104 Phone: 415 403 5434 Fax: 415 362 4557 www.hanjin.com [email protected] Hapag-Lloyd (America) Inc. 180 Grand Ave, Ste. 1535 Oakland, CA 94612 Phone: 510 286 1946 Fax: 510 266 1954 www.hapag-lloyd.com [email protected] Horizon Lines 1425 Maritime St. Oakland, CA 94607 Phone: 510 271 1400 Fax: 510 271 1416 www.horizonlines.com [email protected] Hyundai American Shipping Agency 114 Sansome St., Ste. 910 San Francisco, CA 94104 Phone: 415 676 3080 Fax: 415 676 3098 www.hmm21.com [email protected] K-Line 3478 Buskirk Ave., Ste.