Dissertation, Complete File, Attempt 4

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Student Handbook

Student/ Parent Handbook 2021-2022 Table of Contents Table of Contents 1 Peoria Notre Dame High School Statement regarding Student/ Parent Handbook 7 Catholic School Statement of Purpose 7 History 8 Mission Statement 9 Statement of Philosophy 9 Vision Statement 11 Governance Structure 11 Administrative Office Hours 12 Student School Hours 12 Admissions Policy—Incoming Freshmen 12 Admissions Policy—Transfer Students 13 Admissions Policy—Students with Special Learning Needs 14 Admissions Policy—Non-Citizens 15 Residency Requirement for Students 15 Academics 16 General Information 16 Academic Support Program 16 Student Grade Report 17 Academic Status 17 Honor Roll 18 Grading System Equivalency Table 18 Grade “AU” 18 Grade “I” 18 Grade “M” 19 Grade “P” 19 Grade “WP” 19 Grade “WF” 19 Class Rank 19 Final Exams 20 College Transfer Credits 21 Final Grade 21 Graduation Requirements 21 Counseling Center Services 22 Course Selection 22 Christian Service Program 23 Homework 23 2 Home School Students 23 National Honor Society 24 Summer School/ Credit Recovery 24 Withdrawal Policy—Transfer to Another School 24 Withdrawal Policy—Dropping a Scheduled Course 25 Student Rules and Regulations 25 Attendance Policy 25 Excused Absence 26 School-Sponsored Events/Activities Absence 27 Limited Absence 27 Accumulated Absences 27 Truancy—School Absence 28 Truancy—Class Absence 28 Suspension—Authorized Absence 28 Early Dismissal—Student Request 29 Early Dismissal—School-Sponsored Activity 29 Early Dismissal—Due to Illness 29 Tardiness—School 29 Tardiness—Class 30 -

Archbishop John J. Williams

Record Group I.06.01 John Joseph Williams Papers, 1852-1907 Introduction & Index Archives, Archdiocese of Boston Introduction Biographical Sketch Scope and Content Content List (A-Z) Subject Index Introduction The John Joseph Williams papers held by the Archives of the Archdiocese of Boston span the years 1852-1907. The collection consists of original letters and documents from the year that Williams was assigned to what was to become St. Joseph’s parish in the West End of Boston until his death 55 years later. The papers number approximately 815 items and are contained in 282 folders arranged alphabetically by correspondent in five manuscript boxes. It is probable that the Williams papers were first put into some kind of order in the Archives in the 1930s when Fathers Robert h. Lord, John E. Sexton, and Edward T. Harrington were researching and writing their History of the Archdiocese of Boston, 1604-1943. At this time the original manuscripts held by the Archdiocese were placed individually in folders and arranged chronologically in file cabinets. One cabinet contained original material and another held typescripts, photostats, and other copies of documents held by other Archives that were gathered as part of the research effort. The outside of each folder noted the author and the recipient of the letter. In addition, several letters were sound in another section of the Archives. It is apparent that these letters were placed in the Archives after Lord, Sexton, and Harrington had completed their initial arrangement of manuscripts relating to the history of the Archdiocese of Boston. In preparing this collection of the original Williams material, a calendar was produced. -

The Catholic University of America A

THE CATHOLIC UNIVERSITY OF AMERICA A Manual of Prayers for the Use of the Catholic Laity: A Neglected Catechetical Text of the Third Plenary Council of Baltimore A DISSERTATION Submitted to the Faculty of the School of Theology and Religious Studies Of The Catholic University of America In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree Doctor of Philosophy © Copyright All Rights Reserved By John H. Osman Washington, D.C. 2015 A Manual of Prayers for the Use of the Catholic Laity: A Neglected Catechetical Text of the Third Plenary Council of Baltimore John H. Osman, Ph.D. Director: Joseph M. White, Ph.D. At the 1884 Third Plenary Council of Baltimore, the US Catholic bishops commissioned a national prayer book titled the Manual of Prayers for the Use of the Catholic Laity and the widely-known Baltimore Catechism. This study examines the Manual’s genesis, contents, and publication history to understand its contribution to the Church’s teaching efforts. To account for the Manual’s contents, the study describes prayer book genres developed in the British Isles that shaped similar publications for use by American Catholics. The study considers the critiques of bishops and others concerning US-published prayer books, and episcopal decrees to address their weak theological content. To improve understanding of the Church’s liturgy, the bishops commissioned a prayer book for the laity containing selections from Roman liturgical books. The study quantifies the text’s sources from liturgical and devotional books. The book’s compiler, Rev. Clarence Woodman, C.S.P., adopted the English manual prayer book genre while most of the book’s content derived from the Roman Missal, Breviary, and Ritual, albeit augmented with highly regarded English and US prayers and instructions. -

Cathedral Project Is Completed

Celebrating St. Teresa of Kolkata This issue of The Catholic Post includes several pages devoted to the mission and legacy of St. Teresa of Kolkata, the “Saint of the Gutters” who was canonized Sunday at St. Peter’s Square in Vatican City. Along with the story of the canonization Mass on page 3 is an update on the Missionaries of Charity’s 25 years of service in Peoria and plans for a commemorative Mass at St. Mary’s Cathedral next Saturday, Sept. 10. Also in this issue: l Catholic school students around diocese learn about her, page 4 l A new book about her is reviewed on our Book Page, page 8, and l More of our readers’ Mother Teresa memories, experiences, page 21 Newspaper of the Diocese of Peoria The Sunday, Sept. 11, 2016 Vol. 82,— No. 19 Catholic P ST In this— issue Cathedral Joy as St. Edward School project is reopens in Chillicothe: P2 completed ‘Good work Local couple’s marriage is and well done!’ blessed by Pope Francis: P10 The completion of an extensive, three- year restoration of St. Mary’s Cathedral in Peoria was celebrated as part of Founder’s Weekend ceremonies Aug. 24-28. Stories and color photographs from the major events, which also marked 100 years since the death of Bishop John Lancaster Spalding — the first Bishop of Peoria — are found in a four-page pull-out section in the center of this issue of The Catholic Post. Galesburg, Champaign and “Good work and well done,” said Bishop Bloomington to host statue: P17 Daniel R. -

December 2020 Timeline Newsletter

Fall 2020 Vol. 26, Issue 4 TIMELINE STAFF From the Office Colleen O. Johnson Maureen Naughtin The American Alliance of Museums reports that one-third (33%) of museum Executive Director Curator directors surveyed confirmed there was a “significant risk” of closing permanently Janet Gysin Office Manager by next fall, or they “didn’t know” if they would survive. The last eight months have been some of the most challenging the Peoria Historical Society has seen. OFFICERS Plans that were made for events, History Bus Tours, the de Tonti dinner, Holiday Kathy Ma Beth Johnson Home Tour and open houses were all reinvented or canceled. Operational income President Secretary and revenue for upkeep of our two beautiful museum houses has been cut Zach Oyler Leann Johnson significantly due to these changes. Vice President Past President But we live in the Peoria area, and we are resilient. Membership is currently Clayton Hill Treasurer 117% of expected budget. That shows the support we have from our community. Additional donations have far exceeded our expectations as well. All that is TRUSTEES still not enough to make up the difference in the loss of revenue from our major Lisa Arcot Nicholas J. Hornickle fundraising. We adjusted by significantly cutting operational expenses and went Edward Barry, Jr. Marcia Johnson to a reduced office staff and office hours. I am proud of the fiscally responsible Jim Carballido James Kosner management and dedication from our staff and Board of Trustees. Peoria Riverfront Museum Michele Lehman We ask you to consider making a generous end-of-year donation. Your donation Lee Fosburgh Susie Papenhause will go towards keeping our museum houses -- the John C. -

Hot Re Dartic -Si DI5CS-9Va5l-5(Empeia-Vlctv15\/S- Vlve •9\Yasl- CRAS-Morltuieys;

••'- S-'^: i'--i' -i;' V, -^^SL,^ cu mm Hot re Dartic -si DI5CS-9VA5l-5(EmPeia-VlCTV15\/S- Vlve •9\yASl- CRAS-MORlTUieyS; Vol.. L. NOTRE DAME, INDIANA, NOVEMBER 4. 1916. No. 7.- funeral; another public calamity will soon Age, dim the remembrance of his death in the pubHc - mind," yet to all who love true gireatness of BY ARTHUR HOrE spirit, Spalding's, spirit will be immortal. It is seldom that a country as new as America |-|E was old and bent and tattered and torn, receives a genius so purely intellectual. The - He walked with a jerk, and his head unshorn. stirring times of his youth and early manhood . Bobbed and nodded a sad adieu would seem to have almost forced his talents To the world of to-day,^to me and you. into a circle of public activities. Unsettled as He was crooked and lame, andleaned on a staff. the period was in national affairs, it yet saw The breeze raised his hair as the wind does chaff. greater rehgious turmoil. The long ~ stniggle And the scattered thoughts of his time-worn mind between North and South was just beginning. Fle^v here and there as snow in the wind. When Spalding was seven years old, Webster thundered out his Seventh of March speech:- His voice was shaky, but sweet and soft. it was at Ashland, near Spalding's birth-- Like the tremulo in the organ-loft; ~place that the great Compromiser, Henry Clay, His smile, as soothing as the note that falls sought peace and rest in his attempt to-solve. -

Catholicism in an American Environment: the Early Years

Theological Studies 50 (1989) CATHOLICISM IN AN AMERICAN ENVIRONMENT: THE EARLY YEARS JAMES HENNESEY, S.J. Canisius College, Buffalo, Ν. Y. OES CHURCH history matter? That rather fundamental question was D asked by Richard Price in a review of W. H. C. Frend's The Rise of Christianity. His reply, all too accurate, was, "The answer given by the theologians is a verbal *yes' that thinly hides a mental 'no.' " Liberals like to appeal to a more primitive past, but only in support of views independently formulated on other grounds, while "conservatives assert a development of doctrine that makes present belief normative and early belief embryonic."1 Owen Chadwick has expressed himself puzzled when either of these approaches occurs in Roman Catholic circles. Catholics, he wrote, profess to take tradition seriously, and "commitment to tradi tion is also a commitment to history, and a main reason why the study of Christian history is inescapable in Catholic teaching."2 If Roman Catholics take tradition as seriously as we say we do (e.g., in chapter 2 of Dei verbum, Vatican IFs Constitution on Divine Revelation), then serious study of the Church's history is a necessity, because there we come to know the "teaching, life, and worship" of the Christian commu nity down the ages, and so are helped to an appreciation of what is the authentic tradition. Historical study leads to "a sense of the Catholic tradition as composed of historically conditioned phenomena," a "series of formulations of the one content of faith diversifying and finding expression in different cultural contexts."3 It is with one such context that the present essay is concerned, that of English Colonial America, specifically the Maryland colony, and then the United States until 1870. -

January 17, 2021 Second Sunday in Ordinary Time

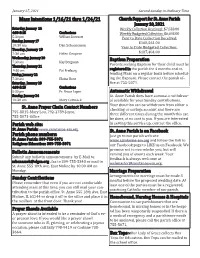

January 17, 2021 Second Sunday in Ordinary Time Mass Intentions 1/16/21 thru 1/24/21 Church Support for St. Anne Parish January 10, 2021 Saturday, January 16 Weekly Collection Received: $7,533.00 4:30-5:15 Confessions Weekly Budgeted Collection: $6,693.00 5:30 pm William Dowsett Year to Date Collection Received: Sunday, January 17 $168,561.00 10:30 am Dan Schueneman Year to Date Budgeted Collection: Tuesday, January 19 7:30 am Helen Deopere $187,404.00 Wednesday, January 20 Baptism Preparation 7:30 am Kay Bergman Parents seeking Baptism for their child must be Thursday, January 21 9:30 am Pat Freiburg registered in the parish for 4 months and at- Friday, January 22 tending Mass on a regular basis before schedul- 7:30 am Elaine Hunt ing the Baptism. Please contact the parish of- Saturday, January 23 fice at 755-5071. 4:30-5:15 Confessions 5:30 pm Fr. Bruce Lopez Automatic Withdrawal Sunday, January 24 St. Anne Parish does have automatic withdraw- 10:30 am Mary Carmack al available for your Sunday contributions. St. Anne Prayer Chain Contact Numbers Your donation can be withdrawn from either a checking or savings account and there are 755-8815-Mary Lou, 792-2789-Joyce, three different times during the month this can 755-5071-Office be done, at no cost to you. If you are interested Parish web site: in setting this service up, contact the office. St. Anne Parish: www.saintanne-em.org St. Anne Parish is on Facebook Parish phone numbers: Just go to our parish web site St. -

Cathedral of Saint Mary of the Immaculate Conception

Cathedral of Saint Mary of the Immaculate Conception Peoria, Illinois A Self-Guided Tour DISCOVER SAINT MARY’S Welcome to Peoria's Cathedral! In the middle ages, it was common for cathedrals to decorate their floors with elaborate labyrinths. These mazes in stone were very physical metaphors for the intentional wandering of the spiritual life. While there is no labyrinth in this cathedral, I invite you to wander nonetheless. This booklet is not designed to be an exhaustive historical guide or museum catalogue. This is not a theme park map to move you from point to point. Instead, we hope to provide a bit of history, a theological context, and an overview of this cathedral that is mother-church to Catholics across Central Illinois. I have been praying in this church both as a seminarian and a priest for over a decade. Over these past few years witnessing the grand restoration and parish life, I have especially been spending a lot of time here. I still never tire of wandering the church, talking to saints who are old friends, discovering new details in the windows, and gazing at the stars. I invite you to wander, to wonder, to pray. St. Mary of the Immaculate Conception, pray for us! Fr. Alexander Millar Rector 2 HISTORY OF SAINT MARY CATHEDRAL In 1851, Bishop James VandeVelde of Chicago asked a Vincentian missionary, Father Alphonse Montouri, CM, to build a new church in Peoria, offering him $200 to carry out the plan. In a year, St. Mary’s Church (right) was built and was said to be one of the finest churches between Chicago and St. -

Spring 2009 Cushwa Center Activities

AMERICAN CATHOLIC STUDIES NEWSLETTE R CUSHWA CENTER FOR THE STUDY OF AMERICAN CATHOLICISM When Faith and Reason Meet: The Legacy of John Zahm, C.S.C. David B. Burrell, C.S.C. hen the Library which more people have lost their lives the party. It is not that Zahm’s talents of Congress to pseudo-scientific ideologies than did went completely unrecognized. In 1887, began planning in the rest of human history, he moved Indiana University’s president had invited its millennial to correct both lacunae. He chose a him to speak on “the Catholic Church symposium in philosopher to comment on religion, and modern science” at Indiana W 1999, librarian the current archbishop of Chicago, University. One local reviewer was James Billington consulted the agenda Cardinal Francis George, O.M.I., whose impressed enough to comment that for the previous centenary celebration prognosis for the central religious issue “unlike many a Protestant minister, only to find that there had been no rep - in 21st century — dialogue between Father Zahm knew what he believed, resentative of religion or the arts on the Catholics and Muslims — would high - where he got his belief, and how to program. The mindset prevailing in light the relevance of the subject even sustain himself in the same.” Southern 1899 apparently had trusted that “sci - more decisively. But let us first focus on Indiana was far from Washington, ence” would suffice to lead humankind the climate in 1899, when Notre Dame’s however, and such trenchant criticism along the march of progress so evident John Zahm had found a persuasive voice of the de facto religious establishment since reason had displaced obscurantism. -

John Lancaster Spalding: Prelate and Philosopher of Catholic Education

John Lancaster Spalding: Prelate and Philosopher of Catholic Education LUCINDA A. NOLAN Religion is judged by its influence on faith and conduct, on hope and love, on righteousness and life–by the education it gives. –John Lancaster Spalding (1905, 129) o single bishop in the history of the American Catholic hierarchy Nhas commanded the respect and attention of scholars in the area of religious education as much as John Lancaster Spalding (1840-1919), first bishop of Peoria, Illinois. While written essays and lectures give the reader of history a record of his philosophy of education, he was no mere theorist. Through the decades of his religious life which spanned the years between the Civil and First World Wars, Spalding collaborated on the production of the Baltimore Catechism (1885), was instrumental in the founding of the Catholic University of America, heralded women’s education, edited textbook series, and modeled the pedagogies he extolled in his writings. While falling short of developing a systematic philosophical treatment of education, Spalding nevertheless stressed the importance of religious education and the roles of family, church, state, and school in the development of Christian moral values throughout his long career (De Hovre 1934, 173). Following a brief biography, this chapter examines the philosophical underpinnings of Spalding’s writings on education and concludes with the identification of his major contributions to Catholic religious education in this country. The case for the singularity of this bishop’s concern for Catholic education in the JOHN LANCASTER SPALDING 21 United States is its core focus. The author is indebted to many fine historians who have built up a substantial body of work on this giant of the American Catholic Church. -

Theocratic Governance and the Divergent Catholic Cultural Groups in the USA Charles L

Eastern Michigan University DigitalCommons@EMU Master's Theses, and Doctoral Dissertations, and Master's Theses and Doctoral Dissertations Graduate Capstone Projects 3-19-2012 Theocratic governance and the divergent Catholic cultural groups in the USA Charles L. Muwonge Follow this and additional works at: http://commons.emich.edu/theses Part of the Education Commons Recommended Citation Muwonge, Charles L., "Theocratic governance and the divergent Catholic cultural groups in the USA" (2012). Master's Theses and Doctoral Dissertations. 406. http://commons.emich.edu/theses/406 This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Master's Theses, and Doctoral Dissertations, and Graduate Capstone Projects at DigitalCommons@EMU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses and Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@EMU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Theocratic Governance and the Divergent Catholic Cultural Groups in the USA by Charles L. Muwonge Dissertation Submitted to the Department of Leadership and Counseling Eastern Michigan University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF EDUCATION Dissertation Committee: James Barott, PhD, Chair Jaclynn Tracy, PhD Ronald Flowers, EdD John Palladino, PhD Ypsilanti, Michigan March 19, 2012 Dedication My mother Anastanzia ii Acknowledgments To all those who supported and guided me in this reflective journey: Dr. Barott, my Chair, who allowed me to learn by apprenticeship; committee members Dr. Jaclynn Tracy, Dr. Ronald Flowers, and Dr. John Palladino; Faculty, staff, and graduate assistants in the Department of Leadership and Counseling at EMU – my home away from home for the last ten years; Donna Echeverria and Norma Ross, my editors; my sponsors, the Roberts family, Horvath family, Diane Nowakowski; and Jenkins-Tracy Scholarship program as well as family members, I extend my heartfelt gratitude.