John Lancaster Spalding: Prelate and Philosopher of Catholic Education

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Student Handbook

Student/ Parent Handbook 2021-2022 Table of Contents Table of Contents 1 Peoria Notre Dame High School Statement regarding Student/ Parent Handbook 7 Catholic School Statement of Purpose 7 History 8 Mission Statement 9 Statement of Philosophy 9 Vision Statement 11 Governance Structure 11 Administrative Office Hours 12 Student School Hours 12 Admissions Policy—Incoming Freshmen 12 Admissions Policy—Transfer Students 13 Admissions Policy—Students with Special Learning Needs 14 Admissions Policy—Non-Citizens 15 Residency Requirement for Students 15 Academics 16 General Information 16 Academic Support Program 16 Student Grade Report 17 Academic Status 17 Honor Roll 18 Grading System Equivalency Table 18 Grade “AU” 18 Grade “I” 18 Grade “M” 19 Grade “P” 19 Grade “WP” 19 Grade “WF” 19 Class Rank 19 Final Exams 20 College Transfer Credits 21 Final Grade 21 Graduation Requirements 21 Counseling Center Services 22 Course Selection 22 Christian Service Program 23 Homework 23 2 Home School Students 23 National Honor Society 24 Summer School/ Credit Recovery 24 Withdrawal Policy—Transfer to Another School 24 Withdrawal Policy—Dropping a Scheduled Course 25 Student Rules and Regulations 25 Attendance Policy 25 Excused Absence 26 School-Sponsored Events/Activities Absence 27 Limited Absence 27 Accumulated Absences 27 Truancy—School Absence 28 Truancy—Class Absence 28 Suspension—Authorized Absence 28 Early Dismissal—Student Request 29 Early Dismissal—School-Sponsored Activity 29 Early Dismissal—Due to Illness 29 Tardiness—School 29 Tardiness—Class 30 -

Historical Notes on the Canon Law on Solemnized Marriage

The Catholic Lawyer Volume 2 Number 2 Volume 2, April 1956, Number 2 Article 3 Historical Notes on the Canon Law on Solemnized Marriage William F. Cahill, B.A., J.C.D. Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.stjohns.edu/tcl Part of the Catholic Studies Commons This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at St. John's Law Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Catholic Lawyer by an authorized editor of St. John's Law Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The nature and importance of the Catholic marriage ceremony is best understood in the light of historicalantecedents. With such a perspective, the canon law is not likely to seem arbitrary. HISTORICAL NOTES ON THE CANON LAW ON SOLEMNIZED MARRIAGE WILLIAM F. CAHILL, B.A., J.C.D.* T HE law of the Catholic Church requires, under pain of nullity, that the marriages of Catholics shall be celebrated in the presence of the parties, of an authorized priest and of two witnesses.1 That law is the product of an historical development. The present legislation con- sidered apart from its historical antecedents can be made to seem arbitrary. Indeed, if the historical background is misconceived, the 2 present law may be seen as tyrannical. This essay briefly states the correlation between the present canons and their antecedents in history. For clarity, historical notes are not put in one place, but follow each of the four headings under which the present Church discipline is described. -

Archbishop John J. Williams

Record Group I.06.01 John Joseph Williams Papers, 1852-1907 Introduction & Index Archives, Archdiocese of Boston Introduction Biographical Sketch Scope and Content Content List (A-Z) Subject Index Introduction The John Joseph Williams papers held by the Archives of the Archdiocese of Boston span the years 1852-1907. The collection consists of original letters and documents from the year that Williams was assigned to what was to become St. Joseph’s parish in the West End of Boston until his death 55 years later. The papers number approximately 815 items and are contained in 282 folders arranged alphabetically by correspondent in five manuscript boxes. It is probable that the Williams papers were first put into some kind of order in the Archives in the 1930s when Fathers Robert h. Lord, John E. Sexton, and Edward T. Harrington were researching and writing their History of the Archdiocese of Boston, 1604-1943. At this time the original manuscripts held by the Archdiocese were placed individually in folders and arranged chronologically in file cabinets. One cabinet contained original material and another held typescripts, photostats, and other copies of documents held by other Archives that were gathered as part of the research effort. The outside of each folder noted the author and the recipient of the letter. In addition, several letters were sound in another section of the Archives. It is apparent that these letters were placed in the Archives after Lord, Sexton, and Harrington had completed their initial arrangement of manuscripts relating to the history of the Archdiocese of Boston. In preparing this collection of the original Williams material, a calendar was produced. -

John Carroll and the Origins of an American Catholic Church, 1783–1815 Author(S): Catherine O’Donnell Source: the William and Mary Quarterly, Vol

John Carroll and the Origins of an American Catholic Church, 1783–1815 Author(s): Catherine O’Donnell Source: The William and Mary Quarterly, Vol. 68, No. 1 (January 2011), pp. 101-126 Published by: Omohundro Institute of Early American History and Culture Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.5309/willmaryquar.68.1.0101 Accessed: 17-10-2018 15:23 UTC JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at https://about.jstor.org/terms Omohundro Institute of Early American History and Culture is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to The William and Mary Quarterly This content downloaded from 134.198.197.121 on Wed, 17 Oct 2018 15:23:24 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms 101 John Carroll and the Origins of an American Catholic Church, 1783–1815 Catherine O’Donnell n 1806 Baltimoreans saw ground broken for the first cathedral in the United States. John Carroll, consecrated as the nation’s first Catholic Ibishop in 1790, had commissioned Capitol architect Benjamin Latrobe and worked with him on the building’s design. They planned a neoclassi- cal brick facade and an interior with the cruciform shape, nave, narthex, and chorus of a European cathedral. -

What They Wear the Observer | FEBRUARY 2020 | 1 in the Habit

SPECIAL SECTION FEBRUARY 2020 Inside Poor Clare Colettines ....... 2 Benedictines of Marmion Abbey What .............................. 4 Everyday Wear for Priests ......... 6 Priests’ Vestments ...... 8 Deacons’ Attire .......................... 10 Monsignors’ They Attire .............. 12 Bishops’ Attire ........................... 14 — Text and photos by Amanda Hudson, news editor; design by Sharon Boehlefeld, features editor Wear Learn the names of the everyday and liturgical attire worn by bishops, monsignors, priests, deacons and religious in the Rockford Diocese. And learn what each piece of clothing means in the lives of those who have given themselves to the service of God. What They Wear The Observer | FEBRUARY 2020 | 1 In the Habit Mother Habits Span Centuries Dominica Stein, PCC he wearing n The hood — of habits in humility; religious com- n The belt — purity; munities goes and Tback to the early 300s. n The scapular — The Armenian manual labor. monks founded by For women, a veil Eustatius in 318 was part of the habit, were the first to originating from the have their entire rite of consecrated community virgins as a bride of dress alike. Belt placement Christ. Using a veil was Having “the members an adaptation of the societal practice (dress) the same,” says where married women covered their Mother Dominica Stein, hair when in public. Poor Clare Colettines, “was a Putting on the habit was an symbol of unity. The wearing of outward sign of profession in a the habit was a symbol of leaving religious order. Early on, those the secular life to give oneself to joining an order were clothed in the God.” order’s habit almost immediately. -

Vatican Appoints New Bishop to Diocese of Tucson Bishop of Diocese of the Diocese of Salina in Kansas Becomes Seventh Bishop of Tucson; Installation Mass Nov

PRESS RELEASE Contact: Steff Koeneman Director of Communications Diocese of Tucson 520-419-2272 cell 520-838-2561 office For release Tuesday, Oct. 3. Vatican appoints new bishop to Diocese of Tucson Bishop of Diocese of the Diocese of Salina in Kansas becomes seventh Bishop of Tucson; Installation Mass Nov. 29 Our Holy Father, Pope Francis, has transferred Bishop Edward Joseph Weisenburger from the Diocese of Salina to the Diocese of Tucson, Ariz. The Holy See made the announcement today in Rome. Weisenburger was notified last week by the Apostolic Nuncio, Archbishop Pierre Christophe, that Pope Francis was entrusting to him the pastoral care of the good people of the Diocese of Tucson. Bishop Gerald F. Kicanas, sixth Bishop of Tucson, submitted his resignation in accord with Church law after having reached his 75th birthday. Following today, he will serve as the administrator of the Diocese until Weisenburger's installation. Weisenburger's appointment comes more than a year after Kicanas' offered his retirement. Bishop Kicanas said, “We are blessed that the Holy Father Pope Francis has appointed as our seventh Bishop in the Diocese of Tucson, a caring and loving pastor and shepherd for our community. He will walk with us, listen to us and stand up for us. His many gifts will provide the pastoral leadership we need. He will be a collaborative worker with diocesan personnel, interfaith leaders and all those with responsibility in this vast diocese of 43,000 square miles.” Weisenburger served as a priest of the Archdiocese of Oklahoma City for almost 25 years. On Feb. -

Banquet in Honor of Archpriest Fr. Gomidas Baghsarian

Etching by Vartkes Kaprielian Publication of Sts. Vartanantz Armenian Apostolic Church 402 Broadway, Providence, Rhode Island 02909 Rev. Fr. Kapriel Nazarian, Pastor Office:401.831.6399 Hall:401.831.1830 F ax:401.351.4418 E-mail: [email protected] Website: stsvartanantzchurch.org Vol. LI No. 10 Commemorative Issue October 2016 Banquet in honor of Archpriest Fr. Gomidas Baghsarian Der Gomidas and Yeretzgeen Joanna Baghsarian with their beautiful family (l to r): Nayiri Bekiarian, Jivan Baghsarian, Richard Kanarian, Aram Baghsarian, Lucine Baghsarian (in back), Vana Baghsarian (in front), Yeretzgeen Joanna, Der Gomidas, Athena Kanarian, Armen Baghsarian Message from His Holiness Aram 1 of the arm to begin the Divine Liturgy…”Khorhoort Khorin”…”O Profound Mystery” … “JUST A PERSONAL NOTE” There is no doubt in my mind that everyone present FROM YERETZGEEN JOANNA “encountered God and entered into communion with Him through His Son, Jesus Christ in the power of "THIS IS THE DAY THE the Holy Spirit”. (This is an excerpt from the LORD HAS MADE!" introduction written by Deacon Shant Kazanjian and is found in The Divine Liturgy Book.) “This is the day that the Lord has made! We will rejoice and be glad in it! That shout of acclamation from Der Hayr awakened my senses and before my feet touched the ground, I responded with “Amen! So be it, Padre!” I quickly checked the time on my cell phone and noticed an early morning text from our friend Bobbie Berberian which read: “This is the day that the Lord has made! We will rejoice and be glad in it!” There are 31,102 verses in the Bible. -

A Buddhist Prelate of California (Illustrated.) Editor 65

$1.00 per Year FEBRUARY, 1912 Price, 10 Cents XTbe ©pen Court A MONTHLY MAGAZINE JDcvotcb to tbe Science of TRcliQiont tbe iReligton ot Science* anb tbe £iten6ion ot tbe 'Reliaious parliament fbea Founded by Edward C. Hegeler. UEBER ALLEN GIPFELN 1ST RUH. After a photograph of the original in the hunter's hut on top of the Gickelhahn, (See page 105.) Zhc %en Coutt publisbing Company CHICAGO Per copy, 10 cents (sixpence). Yearly, $1.00 (in the U.P.U., 5s. 6d.). Eatered m Second-Class Matter March 26, 1897, at the Post Office at Chicago, 111. under Act of March j. 1879. Cbpyrii^t by The (^>en Court Publishlnsr Ctompany, 1913. VOL. XXVI. (No. 2.) FEBRUARY, 1912. NO. .669 CONTENTS PAGE Frontispiece. Pico di Mirandola. A Buddhist Prelate of California (Illustrated.) Editor 65 Order of the Buddhist High Mass (Pontifical). The Rt. Rev. Mazzini- ANANDA SVAMI 71 Goethe's Relation to Women. Conclusion. (Illustrated.) Editor 85 Mr. David P. Abbott's Nezv Illusions of the Spirit World. Editor 119 Pico di Mirandola 124 The Art Institute of Chicago 125 Dr. Paul Topinard. Obituary Note (With Portrait) 125 Jesus's Words on the Cross. A. Kampmeier 126 The Divine Child in the Manger. Eb. Nestle 127 Book Reviews and Notes 127 BOOK REMAINDERS NOW ON SALE A $2.00 Book for $1.00 Thirty Copies on Hand Schiller's Gedichte und Dramen Volksausgabe zur Jahrhundertfeier,1905 MIT EINER BIOGRAPHISCHEN EINLEITUNG. VERLAG DES SCHWABISCHEN SCHILLERVEREINS. This fine work was issued in Germany by the Schillerverein of Stuttgart and Marbach on the occasion of the Schiller festival, in May. -

The Catholic University of America A

THE CATHOLIC UNIVERSITY OF AMERICA A Manual of Prayers for the Use of the Catholic Laity: A Neglected Catechetical Text of the Third Plenary Council of Baltimore A DISSERTATION Submitted to the Faculty of the School of Theology and Religious Studies Of The Catholic University of America In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree Doctor of Philosophy © Copyright All Rights Reserved By John H. Osman Washington, D.C. 2015 A Manual of Prayers for the Use of the Catholic Laity: A Neglected Catechetical Text of the Third Plenary Council of Baltimore John H. Osman, Ph.D. Director: Joseph M. White, Ph.D. At the 1884 Third Plenary Council of Baltimore, the US Catholic bishops commissioned a national prayer book titled the Manual of Prayers for the Use of the Catholic Laity and the widely-known Baltimore Catechism. This study examines the Manual’s genesis, contents, and publication history to understand its contribution to the Church’s teaching efforts. To account for the Manual’s contents, the study describes prayer book genres developed in the British Isles that shaped similar publications for use by American Catholics. The study considers the critiques of bishops and others concerning US-published prayer books, and episcopal decrees to address their weak theological content. To improve understanding of the Church’s liturgy, the bishops commissioned a prayer book for the laity containing selections from Roman liturgical books. The study quantifies the text’s sources from liturgical and devotional books. The book’s compiler, Rev. Clarence Woodman, C.S.P., adopted the English manual prayer book genre while most of the book’s content derived from the Roman Missal, Breviary, and Ritual, albeit augmented with highly regarded English and US prayers and instructions. -

Attorneys for Plaintiff JOHN R.E. DOE, a Married

1 Robert E. Pastor, SBN 021963 MONTOYA, JIMENEZ & PASTOR, P.A. 2 3200 North Central Avenue, Suite 2550 3 Phoenix, Arizona 85012 (602) 279-8969 4 Fax: (602) 256-6667 5 repastor(a!mjpattorneys.com 6 Attorneys for Plaintiff 7 8 IN THE SUPERIOR COURT OF THE STATE OF ARIZONA IN AND FOR THE COUNTY OF COCONINO 9 10 JOHN R.E. DOE, a married man, Case No.: OllO 13 603! 1 11 12 Plaintiff, COMPLAINT v. 13 14 THE ROMAN CATHOLIC CHURCH 15 OF THE DIOCESE OF GALLUP, a corporation sole; THE ESTATE OF 16 MONSIGNOR JAMES 17 LINDENMEYER, deceased; JOHN 18 DOE 1-100; JANE DOE 1-100; and 19 Black & White Corporations 1-100, 20 Defendants. 21 Plaintiff, for his complaint, states and alleges the following: 22 JURISDICTION 23 1. Plaintiff, John R.E. Doe, is a resident of Maricopa COlUlty, Arizona. The acts, 24 25 events, and or omissions occurred in Arizona. The cause of action arose in 26 Navajo COlUlty, Arizona. 27 28 - 1 1 2. Defendant The Roman Catholic Church of the Diocese of Gallup (Gallup) is a 2 corporation sole. The presiding Bishops of the Diocese of Gallup during the 3 relevanttimes at issue in this Complaint were Bishop Bernard T. Espe1age 4 (1940-1969), Bishop Jerome J. Hastrich (1969 - 1990), Bishop Donald 5 Edmond Pelotte (1990 -2008), and Bishop James S. Wall (2009 - present). 6 Bishop Wall is presently governing Bishop of the Diocese of Gallup. 7 8 3. TheDiocese of Gallup is incorporated in the State of New Mexico and has its 9 principle place of business in Gallup, New Mexico. -

Cathedral Project Is Completed

Celebrating St. Teresa of Kolkata This issue of The Catholic Post includes several pages devoted to the mission and legacy of St. Teresa of Kolkata, the “Saint of the Gutters” who was canonized Sunday at St. Peter’s Square in Vatican City. Along with the story of the canonization Mass on page 3 is an update on the Missionaries of Charity’s 25 years of service in Peoria and plans for a commemorative Mass at St. Mary’s Cathedral next Saturday, Sept. 10. Also in this issue: l Catholic school students around diocese learn about her, page 4 l A new book about her is reviewed on our Book Page, page 8, and l More of our readers’ Mother Teresa memories, experiences, page 21 Newspaper of the Diocese of Peoria The Sunday, Sept. 11, 2016 Vol. 82,— No. 19 Catholic P ST In this— issue Cathedral Joy as St. Edward School project is reopens in Chillicothe: P2 completed ‘Good work Local couple’s marriage is and well done!’ blessed by Pope Francis: P10 The completion of an extensive, three- year restoration of St. Mary’s Cathedral in Peoria was celebrated as part of Founder’s Weekend ceremonies Aug. 24-28. Stories and color photographs from the major events, which also marked 100 years since the death of Bishop John Lancaster Spalding — the first Bishop of Peoria — are found in a four-page pull-out section in the center of this issue of The Catholic Post. Galesburg, Champaign and “Good work and well done,” said Bishop Bloomington to host statue: P17 Daniel R. -

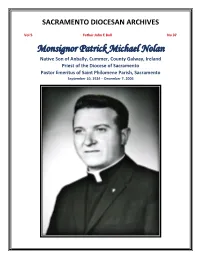

Monsignor Patrick Michael Nolan

SACRAMENTO DIOCESAN ARCHIVES Vol 5 Father John E Boll No 37 Monsignor Patrick Michael Nolan Native Son of Anbally, Cummer, County Galway, Ireland Priest of the Diocese of Sacramento Pastor Emeritus of Saint Philomene Parish, Sacramento September 10, 1924 – December 7, 2006 Patrick Michael Nolan, son of Daniel Nolan and Kate Clancy, was born on September 10, 1924 in Anbally, Cummer, County Galway, Ireland. Three days later, on September 13, he was baptized in Saint Colman’s Church, Cummer. PATRICK BEGINS HIS SCHOOLING Patrick was raised by his grandparents on their farm after his mother died when he was two years of age. He began his elementary schooling in Scoil Mhuire, Furbo, County Galway in 1931 to 1939. He then transferred to Apostolic School, Mungret College, Limerick from 1939 to 1946. He then began his theological studies at All Hallows College, Dublin where he prepared for ordination to the priesthood and service in the Diocese of Sacramento. ORDAINED A PRIEST FOR THE DIOCESE OF SACRAMENTO Patrick Nolan was ordained a priest for the Diocese of Sacramento on June 18, 1950 in All Hallows College Chapel by Bishop Michael O’Reilly of the Diocese of Saint George, Newfoundland. Photo from the book Missionary College of All Hallows, by Kevin Condon, CM All Hallows College, Dublin, Ireland 2 BEGINS PRIESTLY MINISTRY The newly arrived Father Nolan received his first assignment in the Diocese of Sacramento on November 7, 1950 when he was appointed assistant priest of Saint Bernard Parish in Eureka. At this time, Humboldt and Del Norte Counties were part of the Diocese of Sacramento.