Sendfilmstories Compiled by Stefan Chiarantano November 1, 2006

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Che Kokosnuss

Samstag, 4.5., 15.00 Uhr Samstag, 11.5., 15.00 Uhr Samstag, 18.5., 15.00 Uhr Samstag, 25.5., 15.00 Uhr Samstag, 1.6., 15.00 Uhr Samstag, 8.6., 15.00 Uhr Samstag, 15.6., 15.00 Uhr Sonntag, 5.5., 15.00 Uhr Sonntag, 12.5., 15.00 Uhr Sonntag, 19.5., 15.00 Uhr Sonntag, 26.5., 15.00 Uhr Sonntag, 2.6., 15.00 Uhr Sonntag, 9.6., 15.00 Uhr Sonntag, 16.6., 15.00 Uhr DIE WILDHEXE EINMAL MOND PETS RUDOLF DER KLEINE BENJI – SEIN DER KLEINE DRA- UND ZURÜCK DER SCHWARZE SPIROU GRÖSSTES CHE KOKOSNUSS KATER ABENTEUER – AUF IN DEN Der bekannte Showhund Benji DSCHUNGEL Clara ist eigentlich ein ganz Mike Goldwing, ein tapferer, Ein Wohnhaus in Manhattan: Rudolf ist ein kleiner schwar- Mit DER KLEINE SPIROU Der kleine Feuerdrache Kokos- geht auf einem Angeltrip verlo- normaler Teenager. Mit 12 entschlossener 12-jähriger Nachdem die Zweibeiner zur zer Kater, der ein behütetes, findet eine der beliebtesten nuss hofft sehr, dass er auf der ren und strandet in der verlas- Jahren hat sie andere Dinge Junge, ist der Sohn und Enkel Schule oder Arbeit gegangen aber auch ein ruhiges Leben frankobelgischen Comicfigu- Ferieninsel einen Wasserdra- senen Wildnis Oregons. Nun im Kopf als alte Sagen und von NASA-Astronauten. Sein sind, versammeln sich die als Hauskatze führt. Von ren ihren Weg auf die große chen trifft, so wie sein Opa ist er auf sich allein gestellt. Märchen. Das ändert sich, Großvater Frank, ein einst ver- Haustiere und verbringen der Abenteuerlust gepackt, Leinwand. -

"A" - You're Adorable (The Alphabet Song) 1948 Buddy Kaye Fred Wise Sidney Lippman 1 Piano Solo | Twelfth 12Th Street Rag 1914 Euday L

Box Title Year Lyricist if known Composer if known Creator3 Notes # "A" - You're Adorable (The Alphabet Song) 1948 Buddy Kaye Fred Wise Sidney Lippman 1 piano solo | Twelfth 12th Street Rag 1914 Euday L. Bowman Street Rag 1 3rd Man Theme, The (The Harry Lime piano solo | The Theme) 1949 Anton Karas Third Man 1 A, E, I, O, U: The Dance Step Language Song 1937 Louis Vecchio 1 Aba Daba Honeymoon, The 1914 Arthur Fields Walter Donovan 1 Abide With Me 1901 John Wiegand 1 Abilene 1963 John D. Loudermilk Lester Brown 1 About a Quarter to Nine 1935 Al Dubin Harry Warren 1 About Face 1948 Sam Lerner Gerald Marks 1 Abraham 1931 Bob MacGimsey 1 Abraham 1942 Irving Berlin 1 Abraham, Martin and John 1968 Dick Holler 1 Absence Makes the Heart Grow Fonder (For Somebody Else) 1929 Lewis Harry Warren Young 1 Absent 1927 John W. Metcalf 1 Acabaste! (Bolero-Son) 1944 Al Stewart Anselmo Sacasas Castro Valencia Jose Pafumy 1 Ac-cent-tchu-ate the Positive 1944 Johnny Mercer Harold Arlen 1 Ac-cent-tchu-ate the Positive 1944 Johnny Mercer Harold Arlen 1 Accidents Will Happen 1950 Johnny Burke James Van Huesen 1 According to the Moonlight 1935 Jack Yellen Joseph Meyer Herb Magidson 1 Ace In the Hole, The 1909 James Dempsey George Mitchell 1 Acquaint Now Thyself With Him 1960 Michael Head 1 Acres of Diamonds 1959 Arthur Smith 1 Across the Alley From the Alamo 1947 Joe Greene 1 Across the Blue Aegean Sea 1935 Anna Moody Gena Branscombe 1 Across the Bridge of Dreams 1927 Gus Kahn Joe Burke 1 Across the Wide Missouri (A-Roll A-Roll A-Ree) 1951 Ervin Drake Jimmy Shirl 1 Adele 1913 Paul Herve Jean Briquet Edward Paulton Adolph Philipp 1 Adeste Fideles (Portuguese Hymn) 1901 Jas. -

PORTER Burger Battle Nearly Back on Burner Mcdonald's Submits to City Completed Application, Releases Drawing

'"1 '•:'.' r.i'i f:;"*f;".:'v Police watch Groh retires Weavings page11A pageiB pageiC DECEMBERS 1995 VOLUME 24 NUMBER 48 (-, 1 3 SECTIONS, 40 PAGES \ ~ PORTER Burger battle nearly back on burner McDonald's submits to city completed application, releases drawing By Mark S. Krzos News Editor Like burgers on the griddle and fries in oil, the debate over whether to build a Sanibel McDonald's is heating up again. Sanibel architect Ray Fenton sub- mitted his revised rendering and revised floor plan of the proposed McDonald's to the city last week for review. McDonald's released this artist's rendering of the proposed restaurant this week. The company also sub- Fenton said the new design is within mitted a completed application for the required permits. the character of the island and has design was attractive. the island." McDonald's Corp. Bonnie Bonomo eliminated the drive-thru drawn in the "The issue that we started with is McDonald's franchise owner Fred agreed. original plan. that [the restaurant] doesn't bring utili- Frederic said the complete application "We're in the waiting game right Tom Gilhooley, co-chairman of the ty to the island," Gilhooley said. "The has been submitted to the city. now," Bonomo said. "I don't have a opposition group McDonald's;— fact that the rendition is attractive is not "Right now we're waiting for the crystal ball so I really ean't tell you Sanibellians Protecting Our Island the issue; it doesn't bring anything to Planning Commission to give us a what they're going to do. -

DVD Laser Disc Newsletter DVD Reviews Complete Index June 2008

DVD Laser Disc Newsletter DVD Reviews Complete Index June 2008 Title Issue Page *batteries not included May 99 12 "10" Jun 97 5 "Weird Al" Yankovic: The Videos Feb 98 15 'Burbs Jun 99 14 1 Giant Leap Nov 02 14 10 Things I Hate about You Apr 00 10 100 Girls by Bunny Yaeger Feb 99 18 100 Rifles Jul 07 8 100 Years of Horror May 98 20 1000 Eyes of Dr. Mabuse Sep 00 2 101 Dalmatians Jan 00 14 101 Dalmatians Apr 08 11 101 Dalmatians (remake) Jun 98 10 101 Dalmatians II Patch's London Adventure May 03 15 10:30 P.M. Summer Sep 07 6 10th Kingdom Jul 00 15 11th Hour May 08 10 11th of September Moyers in Conversation Jun 02 11 12 Monkeys May 98 14 12 Monkeys (DTS) May 99 8 123 Count with Me Jan 00 15 13 Ghosts Oct 01 4 13 Going on 30 Aug 04 4 13th Warrior Mar 00 5 15 Minutes Sep 01 9 16 Blocks Jul 07 3 1776 Sep 02 3 187 May 00 12 1900 Feb 07 1 1941 May 99 2 1942 A Love Story Oct 02 5 1962 Newport Jazz Festival Feb 04 13 1979 Cotton Bowl Notre Dame vs. Houston Jan 05 18 1984 Jun 03 7 1998 Olympic Winter Games Figure Skating Competit May 99 7 1998 Olympic Winter Games Figure Skating Exhib. Sep 98 13 1998 Olympic Winter Games Hockey Highlights May 99 7 1998 Olympic Winter Games Overall Highlights May 99 7 2 Fast 2 Furious Jan 04 2 2 Movies China 9 Liberty 287/Gone with the West Jul 07 4 Page 1 All back issues are available at $5 each or 12 issues for $47.50. -

Vol.10, No.3 / Spring 2004

The Journal of the Alabama Writers’ Forum STORY TITLE 1 A PARTNERSHIP PROGRAM OF THE ALABAMA STATE COUNCIL ON THE ARTSIRST RAFT F D Vol. 10, No. 2 Spring 2004 VALERIE GRIBBEN Alabama Young Writer 2 STORYFY 04 TITLE STORY TITLE 3 BOARD OF DIRECTORS Editor’s Note President BETTYE FORBUS Dothan Immediate Past President PETER HUGGINS Auburn Dear Readers, Vice-President LINDA HENRY DEAN This issue inaugurates a new year of First Auburn Jay Lamar Secretary Draft. Now in its tenth year of publication, First LEE TAYLOR Monroeville Draft has changed and changed again over the years, often in response to your Treasurer interests and input. From a one-color slightly-larger-than a-newsletter format to J. FAIRLEY MCDONALD III Montgomery its current four-color forty-eight page form, First Draft has expanded its content Writers’ Representative and its readership. DARYL BROWN Florence Some changes are dictated by forces outside our control, and this year Writers’ Representative budget issues loom large. In responding to this force, First Draft will be, for the PHILIP SHIRLEY Jackson, MS foreseeable future, a twice annual publication. Losing two issues a year is not a JAMES DUPREE, JR. decision we would make, left to our own devices, and we hope that the reduc- Montgomery STUART FLYNN tion in issues is a temporary state. Birmingham But in the meantime, we will continue to do the best job we can of covering JULIE FRIEDMAN Fairhope news, publications, and events. Since the publication schedule limits the time- EDWARD M. GEORGE sensitive announcements we can include, we hope you will check the Forum’s Montgomery JOHN HAFNER website—www.writersforum.org--for information on readings, conferences, Mobile and book signings. -

Never Lose Your Library Card! Rated PG Run Time 110 Minutes Free Snacks & Drinks

FIVE RIVERS PUBLIC LIBRARY 301 Walnut St. Parsons WV 26287 Nancy L. Moore, Director Kathy Phillips, Assistant Angela Johnson, Staff Lynnette Adams, Staff Phone/Fax 304-478-3880 www.fiverivers.lib.wv.us ~ [email protected] September – May Hours Support Your Library Monday ……………. 9:00 a - 7:00 p Library has a Run For It Team Tuesday – Friday…8:30 a - 5:00 p $10.00 to walk/run Saturday …………….9:00a – Noon If you are interested in walking, running or just team sponsor for the library. Closed all Legal Holidays th ************************************ Saturday, September 29 at Davis September Happenings 11:00 a.m. 1st – 3rd Closed Labor Day Weekend 18 – Board Meeting @ 5:00 p.m. Painting Party Workshop 18 – Book Club @ 5:00 p.m. Tuesday, 25 24 – Movie Night Monday @ the Library 5:30 – 8:00 p.m. 6:00 p.m., showing “I can only Imagine” $10.00 Reserves your spot PG Run Time 110 mins. Instructor, Ann Cosner 25 - Painting Party Workshop, $10.00 Barn Scene to reserve your spot. 5:30 – 8:00 p 29 – Run For It, Davis WV – Sign in by 9:30 am; Race @ 11:00 am Book Donors Debbie Gutshall;Roger Miller With your Library Card Check with staff to update your card. Memorial Donors In memory of Richard Mauzy, given by Nola DeVilder. Freegal Music is a free music downloading service Book Club Discussion Group providing popular MP3 music for library patrons. Check the Library’s web page for the link. Meets at the library the third Tuesday monthly at http://fiverivers.lib.wv.us/ 5:00 p.m. -

American Humane “Be Kind to Animals Kid” Grows up Call Off The

years “Be Kind to Animals Kid” Grows Up Call Off the Dogs: Working to End Dogfighting Families: Creating Solutions to the Problems Within Turner Classic Movies Animal Filmfest American Humane Protecting Children & Animals Since 1877 Spring 2007 The National Humane Review Volume 6, Number 1 The National Humane Review is published quarterly for professional members, donors and supporters of American Humane. It is distributed via mail and e-mail, and is available online at www.americanhumane.org. President & CEO Marie Belew Wheatley Vice President, Marketing & Communications Randy Blauvelt Publications & Project Manager Teresa Zeigler American Humane May 6-12, 2007 Managing Editor Steve Nayowith Be Kind to Animals Week® is just Contributing Writers Ann Ahlers, Phil Arkow, Michael Blimes, Jone Bouman, a reminder to be kind... Lara Bruce, Tracy Coppola, Anita Horner, Cheryl Kearney, Karen Kessen, Lisa Merkel-Holguin, Heidi Oberman, to Animals, Phil Pierson, Alyson Plummer, Karen Rosa, to Children, Leslie Wilmot, Delise Wyrick to Each Other, Every Day. American Humane Protecting Children & Animals Since 1877 Since 1877, American Humane has been celebrating the The mission of American Humane, as a network of unique bond between humans and animals. This year, individuals and organizations, is to prevent cruelty, American Humane continues this tradition May 6-12, 2007 abuse, neglect and exploitation of children and during Be Kind to Animals Week. animals and to assure that their interests and well- Be a part of the celebration! being are fully, effectively, and humanely guaranteed by an aware and caring society. Visit www.americanhumane.org for more information. American Humane Association 63 Inverness Drive East Denver, CO 80112 (800) 227-4645 Fax: (303) 792-5333 www.americanhumane.org Printed on recycled paper with soy-based ink. -

A Statistical Survey of Sequels, Series Films, Prequels

SEQUEL OR TITLE YEAR STUDIO ORIGINAL TV/DTV RELATED TO DIRECTOR SERIES? STARRING BASED ON RUN TIME ON DVD? VIEWED? NOTES 1918 1985 GUADALUPE YES KEN HARRISON WILLIAM CONVERSE-ROBERTS,HALLIE FOOTE PLAY 94 N ROY SCHEIDER, HELEN 2010 1984 MGM NO 2001: A SPACE ODYSSEY PETER HYAMS SEQUEL MIRREN, JOHN LITHGOW ORIGINAL 116 N JONATHAN TUCKER, JAMES DEBELLO, 100 GIRLS 2001 DREAM ENT YES DTV MICHAEL DAVIS EMANUELLE CHRIQUI, KATHERINE HEIGL ORIGINAL 94 N 100 WOMEN 2002 DREAM ENT NO DTV 100 GIRLS MICHAEL DAVIS SEQUEL CHAD DONELLA, JENNIFER MORRISON ORIGINAL 98 N AKA - GIRL FEVER GLENN CLOSE, JEFF DANIELS, 101 DALMATIANS 1996 WALT DISNEY YES STEPHEN HEREK JOELY RICHARDSON NOVEL 103 Y WILFRED JACKSON, CLYDE GERONIMI, WOLFGANG ROD TAYLOR, BETTY LOU GERSON, 101 DALMATIANS (Animated) 1951 WALT DISNEY YES REITHERMAN MARTHA WENTWORTH, CATE BAUER NOVEL 79 Y 101 DALMATIANS II: PATCH'S LONDON BOBBY LOCKWOOD, SUSAN BLAKESLEE, ADVENTURE 2002 WALT DISNEY NO DTV 101 DALMATIANS (Animated) SEQUEL SAMUEL WEST, KATH SOUCIE ORIGINAL 70 N GLENN CLOSE, GERARD DEPARDIEU, 102 DALMATIANS 2000 WALT DISNEY NO 101 DALMATIANS KEVIN LIMA SEQUEL IOAN GRUFFUDD, ALICE EVANS ORIGINAL 100 N PAUL WALKER, TYRESE GIBSON, 2 FAST, 2 FURIOUS 2003 UNIVERSAL NO FAST AND THE FURIOUS, THE JOHN SINGLETON SEQUEL EVA MENDES, COLE HAUSER ORIGINAL 107 Y KEIR DULLEA, DOUGLAS 2001: A SPACE ODYSSEY 1968 MGM YES STANLEY KUBRICK RAIN NOVEL 141 Y MICHAEL TREANOR, MAX ELLIOT 3 NINJAS 1992 TRI-STAR YES JON TURTLETAUB SLADE, CHAD POWER, VICTOR WONG ORIGINAL 84 N MAX ELLIOT SLADE, VICTOR WONG, 3 NINJAS KICK BACK 1994 TRI-STAR NO 3 NINJAS CHARLES KANGANIS SEQUEL SEAN FOX, J. -

The General Cinema Northpark I & Ii: a Case

THE GENERAL CINEMA NORTHPARK I & II: A CASE STUDY OF A THIRD GENERATION MOVIE THEATER by JEREMY FLOYD SPRACKLEN Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Arlington in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS IN HISTORY THE UNIVERSITY OF TEXAS AT ARLINGTON MAY 2015 Copyright © by Jeremy Floyd Spracklen 2015 All Rights Reserved ii Acknowledgements I would like to express my appreciation for all of the friends and family who encouraged and assisted me throughout my academic career and the writing of this thesis. Specifically, Bob and Diana Cunningham, Cindy and Gary Sharp, and Jessica Tedder. I am humbled by the amount of support that I have been given. I am thankful to my committee, Bart Weiss, Dr. Gerald Saxon, and chair Dr. Robert Fairbanks. Their suggestions and guidance throughout the research and writing of this work cannot be understated. Additionally, I am thankful to Adam Martin for his encyclopedic knowledge of theater buildings. But most of all, I would like to thank Ron Beardmore. His infectious love for the art of projecting film, and the theaters that show them, was the primary factor in choosing this subject for study. April 14, 2015 iii Abstract THE GENERAL CINEMA NORTHPARK I & II: A CASE STUDY OF A THIRD GENERATION MOVIE THEATER Jeremy Spracklen, MA The University of Texas at Arlington, 2015 Supervising Professor: Robert Fairbanks The purpose of this thesis is to present a typology of movie exhibition eras and then explore one of those eras in greater detail by studying a specific market and theater within that market. -

Various Party Crasher (Mixed by Benji Candelario) Mp3, Flac, Wma

Various Party Crasher (Mixed By Benji Candelario) mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Electronic Album: Party Crasher (Mixed By Benji Candelario) Country: US Released: 2000 Style: House, Deep House, Garage House MP3 version RAR size: 1907 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1858 mb WMA version RAR size: 1669 mb Rating: 4.8 Votes: 953 Other Formats: AC3 XM MP1 FLAC MIDI VOC TTA Tracklist Hide Credits I Believe (BC's NYC Heights Mix) 1 –The Absolute 3:20 Featuring – Suzanne PalmerRemix – Benji Candelario 2 –Subslide Rockin' (BC's Prime Time Mix / BC's Beats) 5:49 3 –Benji Candelario Uptown Carnival 3:53 Central Park (Rum De' CoCo) (BC's Park Ride) 4 –Benji Candelario 6:04 Keyboards – Johan Brunkvist Share My Joy (BC's Dub / BC's Rendition Mix) 5 –GTS 9:57 Featuring – Loleatta HollowayRemix – Benji Candelario I Believe (Benji's Classic Mix) 6 –Jamestown 4:28 Featuring – Jocelyn BrownRemix – Benji Candelario Learn To Give (Eric Kupper 12" Mix) 7 –Benji Candelario 6:44 Remix – Eric KupperVocals – Arnold Jarvis 8 –Benji Candelario Frequency Check 5:44 You Don't Know (BC's Remix) 9 –Serious Intentions* 7:18 Remix – Benji Candelario Picking Up Promises (Will Tek/Benji Candelario Remix) 10 –Jocelyn Brown 6:30 Remix – Benji Candelario, Will Tek Learn To Give (Dub Mix) 11 –Benji Candelario 5:22 Vocals – Arnold Jarvis Credits DJ Mix – Benji Candelario Related Music albums to Party Crasher (Mixed By Benji Candelario) by Various Benji Candelario Presents The New Hippie Movement - The Rhythm Risko Benji - Give Me The Vibes Papa Benji / Bobby Ellis - Me Know Me Area Euel Box - For The Love Of Benji Risto Benji - Something New Candelario Y Su Combo - Salsa Vallenata / Ocho Dias Benji Kirkpatrick - Dance In The Shadow Thodoris Triantafillou & CJ Jeff Featuring Benji - Missionary / Dybbuk Benji Mateke & Les Stars 2000 - 1 ère Mi-Temps Jerome Laiter Vs Benji Solis Jr. -

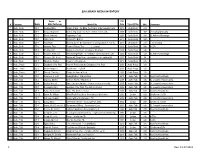

Sjn Library Media Inventory

SJN LIBRARY MEDIA INVENTORY Series or C/R # Category Media Main Performer Media Title Date Type of Film Min. Comments 1 Audio_Book CD-3 Aquilina, Mike Angels of God - the Bible, the Church & the heavenly hosts 2010 AudioBook 210 2 Audio_Book CD-5 Arroyo, Raymond Mother Angelica's Little Book of Life Lessons and… 2007 Audio Book 360 ..Everyday Spirituality 3 Audio_Book CD-2 Bloom, Anthony Beginning to Pray 2004 Audio Book 150 St. Anthony Messenger 4 Audio_Book CD-5 Hahn, Scott Reasons To Believe 2010 Audio Book 360 5 Audio_Book CD-3 Hart, Mark Blessed are the Bored in Spirit - a young Catholic's search.. 2010 AudioBook 210 …for meaning 6 Audio_Book CD-6 Hershey, Terry Power of Pause, The ( 2 copies) 2010 Audio Book 360 6 CD's 7 Audio_Book CD-4 Keating, Karl Apologetics in Action - Keating vs. Ruckman 2008 Audio Book unk 8 Audio_Book CD-2 Nouwen, Henri J.M. With Burning Hearts - a meditation on the Eucharistic Life 2005 Audio Book 120 St. Anthony Messenger 9 Audio_Book CD-2 Nouwen, J.M. Henri Making All Things New - an invitation to the spiritual life 2007 Audio Book 90 10 Audio_Book CD-7 Omartian, Stormie Power of a Praying Life 2010 Audio Book unk 11 Audio_Prayer CD-2 Daughters of St. Paul Pray the Rosary with the Daughters of St. Paul 2001 Audio Prayer 128 12 Audio_Prayer CD-2 Mother Angelica Holy Rosary - EWTN 2005 Audio Prayer 120 13 Audio_Prayer CD-2 Sheedy, Timothy J. Rosary for those in Need 2005 Audio Prayer 120 14 Audio_Talk CD-5 Anderson, C. -

Official Ballot

OFFICIAL BALLOT AFI is a trademark of the American Film Institute. Copyright 2005 American Film Institute. All Rights Reserved. AFI’s 100 Years…100 CHEERS America's Most Inspiring Movies AFI has compiled this ballot of 300 inspiring movies to aid your selection process. Due to the extraordinarily subjective nature of this process, you will no doubt find that AFI's scholars and historians have been unable to include some of your favorite movies in this ballot, so AFI encourages you to utilize the spaces it has included for write-in votes. AFI asks jurors to consider the following in their selection process: CRITERIA FEATURE-LENGTH FICTION FILM Narrative format, typically over 60 minutes in length. AMERICAN FILM English language film with significant creative and/or production elements from the United States. Additionally, only feature-length American films released before January 1, 2005 will be considered. CHEERS Movies that inspire with characters of vision and conviction who face adversity and often make a personal sacrifice for the greater good. Whether these movies end happily or not, they are ultimately triumphant – both filling audiences with hope and empowering them with the spirit of human potential. LEGACY Films whose "cheers" continue to echo across a century of American cinema. 1 ABE LINCOLN IN ILLINOIS RKO, 1940 PRINCIPAL CAST Raymond Massey, Gene Lockhart, Ruth Gordon DIRECTOR John Cromwell PRODUCER Max Gordon SCREENWRITER Robert E. Sherwood Young Abe Lincoln, on a mission for his father, meets Ann Rutledge and finds himself in New Salem, Illinois, where he becomes a member of the legislature. Ann’s death nearly destroys the young man, but he meets the ambitious Mary Todd, who makes him take a stand on slavery.