Diversity Leads 2020

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Toronto PRIMETIMES Newsletter

PRIMEVOLUME 25, NUMBERTIMES 8 – O C T O B E R 2 0 1 9 PRESIDENT’S MESSAGE Hello PrimeTimers Members. October2019 A friendly reminder: do not forget to purchase your Christmas Banquet tickets. You can contact Dennis Longmire or Bill Patterson at torontoprimetimers.gmail.com. As always, I am available to talk if you have any question or concerns. Thanks, Steve Minnie, PTT President Toronto PRIMETIMES Newsletter - October 2019 1 QJR:7 QJR:7 %V R:7 %V R:7 VRJV R:7 7 7 7 7 7 11 .:CC7Q%``:0Q%`1 V`VCC: : V QJ :JR$%1RVR]`:H 1HV .V 6 .VJ]C:7V` .V 6 .VJ]C:7V` QIV$`V: `V :%`:J R $QQ@&C%GQJ.QCR8 : .V Q` VJ$Q`Q`HQ``VV Q` VJ$Q`Q`HQ``VV CQH: 1QJ 1J .1 JV1 CV V` .%` R:7 .%` R:7 )`1R:7 *: %`R:7 *: %`R:7 7 7 7 7 7 *QH1:C 1IV: .V&.%`H. : .V 5V0V`7 .1`R *QH1:C 1IV: .V&.%`H.* `VV *QH1:C 1IV: .V&`Q1 :J .V 5`QQI * `VV . ]`V Q5&.%`H. *: %`R:75V6HV] 2%C7:JR . ]`V Q5&.%`H.0 :GVCC:8 `VV5&.%`H.&.:`CV 0 :GVCC: 2:J%:`7 PTT is always happy to include your events and event suggestions. Your Art Shows, Theatrical Productions, Concerts, and Sporting Events can be promoted here! You’ll be amazed at the turnout! Always believe - if it is of interest to you, it will be of interest to others in our group. [email protected] will get you duly promoted! Thursday coffee will switch to Croissant Tree on Support the generous businesses and Thursday November 7, 2019. -

Gay Pride on Stolen Land: Homonationalism, Queer Asylum

Gay Pride on Stolen Land: Homonationalism, Queer Asylum and Indigenous Sovereignty at the Vancouver Winter Olympics Paper submitted for publication in GLQ: A Journal of Lesbian and Gay Studies August 2012 Abstract In this paper we examine intersections between homonationalism, sport, gay imperialism and white settler colonialism. The 2010 Winter Olympics, held in Vancouver, Canada, produced new articulations between sporting homonationalism, indigenous peoples and immigration policy. For the first time at an Olympic/Paralympic Games, three Pride Houses showcased LGBT athletes and provided support services for LBGT athletes and spectators. Supporting claims for asylum by queers featured prominently in these support services. However, the Olympic events were held on unceded territories of four First Nations, centered in Vancouver which is a settler colonial city. Thus, we examine how this new form of ‘sporting homonationalism’ emerged upon unceded, or stolen, indigenous land of British Columbia in Canada. Specifically, we argue that this new sporting homonationalism was founded upon white settler colonialism and imperialism—two distinct logics of white supremacy (Smith, 2006).1 Smith explained how white supremacy often functions through contradictory, yet interrelated, logics. We argue that distinct logics of white settler colonialism and imperialism shaped the emergence of the Olympic Pride Houses. On the one hand, the Pride Houses showed no solidarity with the major indigenous protest ‘No Olympics On Stolen Land.’ This absence of solidarity between the Pride Houses and the ‘No Olympics On Stolen Land’ protests reveals how thoroughly winter sports – whether elite or gay events — depend on the logics, and material practices, of white settler colonialism. We analyze how 2 the Pride Houses relied on colonial narratives about ’Aboriginal Participation’ in the Olympics and settler notions of ‘land ownership’. -

Safety in Relationships: Trans Folk

Safety in Relationships Trans Folk Febuary 2020 © 2020 QMUNITY and Legal Services Society, BC Second edition: February 2020 First edition: December 2014 ISBN: 978-1-927661-06-2 (print) ISBN: 978-1-927661-08-6 (online) Published on the traditional unceded territory of the Coast Salish peoples, including the territories of the xʷməθkʷəy̓əm (Musqueam), Sḵwx̱wú7mesh (Squamish) and səl̓ ílwətaʔɬ/Selilwitulh (Tsleil-Waututh) Nations. Acknowledgements Writer: QMUNITY Editor: Wendy Barron Designer: Caitlan Kuo Legal reviewer: Manjeet Chana Development coordinators: Patricia Lim and QMUNITY Photos: The Gender Spectrum Collection Inside photos: iStock Thanks to a diverse team of volunteers, and to Safe Choices: a LGBT2SQ support and education program of the Ending Violence Association of BC (EVA BC), for their valuable assistance. This publication may not be reproduced commercially, but copying for other purposes, with credit, is encouraged. This booklet explains the law in general. It isn’t intended to give you legal advice on your particular problem. Each person’s case is different. You may need to get legal help. Information in this booklet is up to date as of February 2020. This booklet helps identify what can make a relationship unsafe and provides resources for people looking for support. Caution: This booklet discusses and gives examples of abuse. Consider having someone with you for support, or plan other kinds of self-care, if reading it might make you feel anxious or distressed. An abusive partner might become violent if they find this booklet or see you reading it. For your safety, read it when they’re not around and keep it somewhere they don’t go. -

CPSR Internship Brochure Information Oct 2020

2021-2020 The Centre for Psychological Services and Research Internship Brochure Introduction The Centre for Psychological Services and Research (CPSR), a training unit of the School of Psychology at the University of Ottawa offers a pre-doctoral internship in both French and English giving interns an opportunity to complete their training in either language. Interns may choose to complete their training in English or French. Appointments begin September 1, 2021and end on August 31, 2022. The stipend is $28,000 paid over the period of an intern's training; an additional $500 is allocated to external applicants to assist with moving costs. The stipend is paid through a bursary. Additional benefits include a three-week vacation and statutory holidays including the period between Christmas and the New Year[1]. In 2021-2022, we anticipate having one full-time position, available to students from Ph.D. programs in clinical psychology other than the University of Ottawa program, and seven full-time positions reserved for students in the Ph.D. Clinical Psychology Training Programme at the University of Ottawa. 1 Positions Available For the internship year 2021-2022 the following internship positions are anticipated: • Adult Clinical (External intern; English or bilingual; CPSR & external rotation; APPIC # 182719) • Three positions, Adult Clinical (uOttawa intern; English, French or bilingual; CPSR & external rotation; APPIC # 182714) • Adult Clinical (uOttawa intern; English or bilingual; CPSR & The Ottawa Hospital[2], APPIC # 182720) • Adult Clinical (uOttawa intern; French; CPSR & Montfort Hospital[2]; APPIC # 182718) • Adult Clinical/Community (uOttawa intern, English or Bilingual; CPSR & CRECS[3]; APPIC # 182717) • Adult/Child/Family Clinical (uOttawa intern, English or bilingual; CPSR & external rotation; APPIC # 182715) 1 Certain external rotations exempt for the period between Christmas and the New Years. -

ADMINISTRATIVE REPORT Report Date: May 9, 2018 Contact: Tim Stevenson Contact No.: 604.873.7247 RTS No.: 12599 Vanrims No.: 08-2

ADMINISTRATIVE REPORT Report Date: May 9, 2018 Contact: Tim Stevenson Contact No.: 604.873.7247 RTS No.: 12599 VanRIMS No.: 08-2000-20 Meeting Date: May 15, 2018 TO: Vancouver City Council FROM: Chief of External Relations and Protocol SUBJECT: Year of the Queer Proclamation and Launch RECOMMENDATION A. THAT in recognition of 15 significant anniversaries celebrated this year by local LGBTTQ organizations, and in recognition of the contributions these organizations have made to Vancouver’s social, cultural and artistic landscape, the City launch a “2018 - Year of the Queer” Proclamation and Launch event. B. THAT Council direct staff to utilize funds designated for the Council approved annual “Pride Week” event at the end of July, and redirect those funds to support a one-time “2018 - Year of the Queer” event at Vancouver City Hall on May 23, 2018. C. THAT Council authorize the 12’ X 24’ Pride Flag and 12’ X 24’ Trans Flag to fly on the north lawn of City Hall from May 23, 2018 – August 19, 2018 as a public acknowledgement of these significant anniversaries. REPORT SUMMARY Vancouver has been enriched by the social, economic, cultural and artistic contributions of the Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, Two-Spirited, Queer (LGBTTQ) community. Twenty-eighteen marks significant anniversaries for 15 local LGBTTQ arts, cultural, community and health organizations, all of which have made substantial contributions to Vancouver’s artistic, social and cultural landscape. In recognition of these anniversaries, it has been recommended that an event at Vancouver City Hall be held from 11 am - 1 pm on Wednesday, May 23 to kick-off the anniversary season on behalf of the celebrating organizations. -

Annual Report to the Community

report to the community [ 2017-2018 ] with you, for you La version francophone du rapport annuel à la communauté est disponible au rapportannuel.hopitalmontfort.com. © 2018, Hôpital Montfort – Direction des communications TABLE OF CONTENT MESSAGE FROM THE LEADERSHIP TEAM 4 TESTIMONIALS 6 Rethink Emergency 6 Restore Calm 10 Train the Future 13 Connect Care 16 THE YEAR AT A GLANCE 19 Improving the clinical sectors 19 Promoting training and research 21 Seeking administrative efficiency 22 Promoting a healthy workplace 24 INSTITUT DU SAVOIR MONTFORT 26 FOUNDATION 27 VOLUNTEERS 28 GOVERNANCE 30 MEDICAL ORGANIZATION 30 SUMMARY OF FINANCIAL STATEMENTS 31 MESSAGE FROM THE LEADERSHIP TEAM This edition of the Annual Report to the Community We are extremely proud of this recognition, especially is inspired by our vision, which is to “become your since the main objective of the accreditation process hospital of reference for outstanding services, is to ensure outstanding healthcare for our patients. designed with you and for you.” This year, we are celebrating the fifth anniversary In four stories, we will describe how the Montfort of our designation as an academic hospital. Since team puts Strategy 21 into practice each and every then, the Institut du Savoir Montfort has reached great day, be it in Emergency, the Mental Health Program, heights; a culture of knowledge is growing among Intensive Care or elsewhere in the hospital, including our members, and the hospital joined the ranks of in fulfilling our mandate as an academic teaching the top 40 major research hospitals in Canada. We hospital. We will also take a brief look at the Montfort put the final touches on an agreement that allows team’s innovations, improvements and successes physicians to devote more time to training the next over the past year. -

Request for Proposals Website Redesign for the Arquives The

Request for Proposals Website redesign for The ArQuives The ArQuives (formally the Canadian Lesbian and Gay Archives) acquires, preserves, protects and gives public access to information related to the LGBTQ2+ experience in Canada. Our goal is to be a significant resource and catalyst for those who strive for a future world where LGBTQ2+ people are accepted, valued, and celebrated. Founded in 1973, The ArQuives is the largest LGBTQ2+ independent archive in the world and is recognized globally as a significant resource for LGBTQ2+ documentary heritage. Archival users from across Canada and around the world visit The ArQuives to conduct research for academic projects, journalistic work, documentary filmmaking and other creative productions. The ArQuives also offers remote services to hundreds of researchers who are unable to visit the archives in person. Our collection includes personal and organizational records, vertical files, a photographic collection (20,000 plus), moving images, posters, audiotapes, cartographic and architectural plans, works of art, textiles, and artifacts (including t-shirts, buttons, matchbooks and banners). The LGBTQ2+ periodicals collection is the largest in the world (10,000 plus titles). As trusted steward of vast holdings, The ArQuives has developed outreach programs that connect the public with the evidence needed to build a strong sense of identity and shared heritage for LGBTQ2+ Canadians. This includes Pride Walk, public lectures, class visits, conference presentations, tours of The ArQuives house and social media posts. We actively engage in partnering with other LGBTQ2+ agencies and archives to provide them with the research services and material content to support their management. We also provide valuable internship experience for undergraduate and graduate students to help foster the next generation of LGBTQ2+ historians and archivists. -

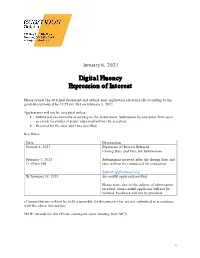

Digital Fluency Expression of Interest

January 6, 2021 Digital Fluency Expression of Interest Please review the attached document and submit your application electronically according to the guidelines provided by 11:59 pm EST on February 3, 2021. Applications will not be accepted unless: • Submitted electronically according to the instructions. Submission by any other form such as email, facsimiles or paper copy mail will not be accepted. • Received by the date and time specified. Key Dates: Date Description January 6, 2021 Expression of Interest Released Closing Date and Time for Submissions February 3, 2021 Submissions received after the closing date and 11:59pm EST time will not be considered for evaluation Submit applications here By February 28, 2021 Successful applicants notified Please note: due to the volume of submissions received, unsuccessful applicants will not be notified. Feedback will not be provided eCampusOntario will not be held responsible for documents that are not submitted in accordance with the above instructions NOTE: Awards for this EOI are contingent upon funding from MCU. 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. BACKGROUND .................................................................................................................... 3 2. DESCRIPTION ....................................................................................................................... 4 WHAT IS DIGITAL FLUENCY? .......................................................................................................... 4 3. PROJECT TYPE ..................................................................................................................... -

October 2016

October 2016 Photo by Dino DiLabio Rest in peace: Mourners gathered at the Notre Dame Basilica to say a final farewell to Ottawa-Vanier MP www.newedinburgh.ca Mauril Bélanger, who passed away Aug. 16 after a short and courageous battle with ALS. Tributes on p. 4. LCBO not on list of Minto Beechwood retail By Jane Heintzman an open question, with the is good news. As of press time, the brickwork possibility of subdividing the Throughout the summer, and glazing are proceeding unit still under active consid- Minto has been collaborating apace at Minto Beechwood, eration. with City of Ottawa plan- and despite some construc- The only piece of hard news ners to sort out the details tion delays over the summer, on the commercial front is of the building’s streetscape Minto remains on target for a that the LCBO will not be in keeping with the city’s February 2017 move-in date among the ground-floor occu- “Complete Street” design, for condo owners. Should pants at Minto Beechwood. an ambitious plan intended there be any further glitches That faint hope went out to accommodate pedestrians, in the timetable, owners will the window with a man- cyclists, motorists and limited have to be notified by the end agement change at LCBO parking for shoppers. At pub- of October. which occasioned a whole- lication time, that design had On the commercial front, sale review of operations, yet to be finalized, but time tenants are slated to take pos- putting expansion options on is tight as Minto is scheduled session in December and to hold for the moment. -

Inhalt Content

Hauptförderung Förderung Supporters INHALT CONTENT 3 GRUSSWORT DES SENATORS FÜR KULTUR UND MEDIEN / WELCOME NOTE BY THE MINISTER OF CULTURE AND MEDIA 6 VORWORT DER FESTIVALLEITUNG / FESTIVAL DIRECTOR’S PREFACE 1 5 TRAILER Institutionelle Partnerschaften 1 7 WETTBEWERBE / COMPETITIONS 21 Jurys / Juries 27 Preise / Awards 29 Internationaler Wettbewerb / International Competition 47 Deutscher Wettbewerb / German Competition 59 Dreifacher Axel / Triple Axel 67 Mo&Friese Kinder Kurzfilm Festival / Create Converge Children’s Short Film Festival 85 LABOR DER GEGENWART / LABORATORY OF THE PRESENT 87 LAB 1 Gestimmtheiten – Das Kino und die Gesten Attunements – Cinema and Gestures 1 09 LAB 2 Afrotopia – In the Present Sense 1 24 LAB 3 Hamburger Positionen / Hamburg Positions 1 33 ARCHIV DER GEGENWART / ARCHIVE OF THE PRESENT 1 35 ARCHIV 1 CFMDC 1 42 ARCHIV 2 Vtape 1 51 OPEN SPACE Mo&Friese wird unterstützt von 1 59 WILD CARD 1 63 DISTRIBUTING 1 75 MORE HAPPENINGS 1 87 INDUSTRY EVENTS 1 97 ANIMATION DAY Medienpartnerschaften 209 KURZFILM AGENTUR HAMBURG 210 DANK / THANK YOU 212 REGISTER 222 BILDNACHWEISE / PICTURE CREDITS Mitgliedschaften 223 IMPRESSUM / IMPRINT 224 FESTIVALINFORMATION PROGRAMMPLAN / SCHEDULE U m s c h l a g / C o v e r 3 INTRO Grußwort des Kultur- senators der Freien und Hansestadt Hamburg: Carsten Brosda Was hält uns als Gesellschaft zusammen? Und um- gekehrt: Was trennt uns voneinander? Der große Theater- mann Max Reinhardt benannte schon 1928 ein vermeint- liches Paradoxon, indem er sagte: »Wir können heute über den Ozean fliegen, hören und sehen, aber der Weg zu uns selbst und zu unserem Nächsten ist sternenweit.« Das ist noch heute nicht ganz von der Hand zu wei- sen – und beschreibt eine ständige Herausforderung: Denn ohne gegenseitiges Vertrauen und gegenseitige Unter- stützung ist gesellschaftlicher Zusammenhalt nichts weiter als eine schöne Idee. -

From Paper, to Microform, to Digital? Serials at the Arquives: Canada's LGBTQ2+ Archives Donald W. Mcleod

From Paper, to Microform, to Digital? Serials at the ArQuives: Canada’s LGBTQ2+ Archives Donald W. McLeod Abstract The ArQuives: Canada’s LGBTQ2+ Archives, founded in 1973, holds one of the largest collections of queer serials in the world, with more than ten thousand titles. Most are on paper, but formats have been evolving. Beginning in the 1980s, the ArQuives participated in small-scale microfilming projects. Microfilming of the collection increased greatly in 2005, when Primary Source Microfilm (PSM) undertook a large project to film a portion of the collection, resulting in 211 reels devoted to international gay and lesbian periodicals and newsletters. The PSM project was later repurposed and expanded by Gale Cengage, beginning in 2015, and forms part of its Archives of Sexuality and Gender online product. This paper examines the evolution of the ArQuives’ serial holdings from paper to microform to digital formats, and explores recent in-house digitization efforts and future prospects for expanding access to these materials. Résumé Les ArQuives : les archives LGBTQ2+ canadiennes, fondées en 1973, détiennent une des plus importantes collections de périodiques queer au monde, comprenant plus de dix mille titres. La majorité sont sur papier, mais les formats sont en évolution. Depuis les années 1980, les ArQuives participent à des projets de microfilmage de petite envergure. Le microfilmage a vu une augmentation importante en 2005, lorsque Primary Source Microfilm (PSM) a entrepris un grand projet consistant à microfilmer une portion de la collection, ayant pour résultat 211 bobines consacrées aux bulletins et périodiques gais et lesbiens internationaux. Par la suite, à partir de 2015, le projet PSM a été transformé et élargi par Gale Cengage, et fait maintenant partie de son produit en ligne Archives of Sexuality and Gender. -

Supreme Court of Canada (On Appeal from the Court of Appeal for Ontario)

SCC File No. 37209 SUPREME COURT OF CANADA (ON APPEAL FROM THE COURT OF APPEAL FOR ONTARIO) BETWEEN: TRINITY WESTERN UNIVERSITY and BRAYDEN VOLKENANT Appellants -and- THE LAW SOCIETY OF UPPER CANADA Respondent -and- ATTORNEY GENERAL OF ONTARIO Intervener -and- START PROUD and OUTLAWS Proposed Intervener MOTION FOR LEAVE TO INTERVENE OF THE PROPOSED INTERVENER, START PROUD and OUTLAWS (Rules 47 and 55 of the Rules ofthe Supreme Court of Canada) GOLDBLATTPARTNERSLLP GOLDBLATTPARTNERSLLP 20 Dundas Street West, Suite 1039 30 Metcalfe Street, Suite 500 Toronto, ON M5G 2C2 Ottawa, ON K1P 5L4 Marlys Edwardh Colleen Bauman Vanessa Payne Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] Tel: 416-979-4380 Tel: 613-482-2463 Fax: 416-979-4430 Fax: 613-235-3041 2 PAUL JONATHAN SAGUIL 66 Wellington St. West TD Tower, P.O. Box 1 Toronto ON MSK 1A2 Paul Jonathan Saguil Email: [email protected] Tel: 416-308-1719 MARTIN+ ASSOCIATES 863 Hamilton Street Vancouver, BC V6B 2R7 Frances Mahon Email: [email protected] Tel: 604-682-4200 Agent for the Proposed Intervener, Counsel for the Proposed Intervener, Start Proud and OUTlaws Start Proud and OUTlaws ORIGINAL TO: The Registrar Supreme Court of Canada 301 Wellington Street Ottawa, ON KIA OJl 3 COPIES TO: BENNETT JONES LLP BENNETT JONES LLP 3400 One First Canadian Place World Exchange Plaza P.O. Box 130 I900- 45 O'Connor Street Toronto, ON M5X IA4 Ottawa, ON KIP IA4 Robert W. Stanley Mark Jewett QC Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] Ranjan Aganval Tel: 6I3-683-2328 Email: [email protected] Fax: 6I3-683-2323 Tel: 4I6-863-I200 Fax: 4I6-863-I2I6 KUHNLLP IOO- 32I60 S Fraser Way Abbotsford, BC V2T I W5 Kevin L.