The Proposed Twenty-Fifth Amendment to the Constitution

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lower Manhattan

WASHINGTON STREET IS 131/ CANAL STREETCanal Street M1 bus Chinatown M103 bus M YMCA M NQRW (weekday extension) HESTER STREET M20 bus Canal St Canal to W 147 St via to E 125 St via 103 20 Post Office 3 & Lexington Avs VESTRY STREET to W 63 St/Bway via Street 5 & Madison Avs 7 & 8 Avs VARICK STREET B= YORK ST AVENUE OF THE AMERICAS 6 only6 Canal Street Firehouse ACE LISPENARD STREET Canal Street D= LAIGHT STREET HOLLAND AT&T Building Chinatown JMZ CANAL STREET TUNNEL Most Precious EXIT Health Clinic Blood Church COLLISTER STREET CANAL STREET WEST STREET Beach NY Chinese B BEACH STStreet Baptist Church 51 Park WALKER STREET St Barbara Eldridge St Manhattan Express Bus Service Chinese Greek Orthodox Synagogue HUDSON STREET ®0= Merchants’ Fifth Police Church Precinct FORSYTH STREET 94 Association MOTT STREET First N œ0= to Lower Manhattan ERICSSON PolicePL Chinese BOWERY Confucius M Precinct ∑0= 140 Community Plaza Center 22 WHITE ST M HUBERT STREET M9 bus to M PIKE STREET X Grand Central Terminal to Chinatown84 Eastern States CHURCH STREET Buddhist Temple Union Square 9 15 BEACH STREET Franklin Civic of America 25 Furnace Center NY Chinatown M15 bus NORTH MOORE STREET WEST BROADWAY World Financial Center Synagogue BAXTER STREET Transfiguration Franklin Archive BROADWAY NY City Senior Center Kindergarten to E 126 St FINN Civil & BAYARD STREET Asian Arts School FRANKLIN PL Municipal via 1 & 2 Avs SQUARE STREET CENTRE Center X Street Courthouse Upper East Side to FRANKLIN STREET CORTLANDT ALLEY 1 Buddhist Temple PS 124 90 Criminal Kuan Yin World -

The Bayh-Dole Act at 25

The Bayh-Dole Act at 25 A publication of BayhDole25, Inc 242 West 30th, Suite 801 New York, New York 10001 phone: (646) 827-2196 web: www.bayhdole25.org e-mail: [email protected] April 17, 2006 © 2006 Bayhdole25, Inc. Table of Contents INTRODUCTION....................................................................................................................................... 1 Overview .............................................................................................................................................. 2 Diagram 1: Commercialization of Federally-Funded Research Before the Bayh Dole Act.................. 3 HISTORICAL ORIGINS OF BAYH-DOLE................................................................................................4 Property rights framework .................................................................................................................... 4 Public financing of higher education .................................................................................................... 4 Universities engage in research........................................................................................................... 6 World War II: role of technological innovation...................................................................................... 7 Science: the endless frontier................................................................................................................ 8 Table 1: Federal Support for Academic R & D, 1960-2000 (millions of 1996 dollars) -

To the William Howard Taft Papers. Volume 1

THE L I 13 R A R Y 0 F CO 0.: G R 1 ~ ~ ~ • P R I ~ ~ I I) I ~ \J T ~' PAP E R ~ J N 1) E X ~ E R IE S INDEX TO THE William Howard Taft Papers LIBRARY OF CONGRESS • PRESIDENTS' PAPERS INDEX SERIES INDEX TO THE William Ho-ward Taft Papers VOLUME 1 INTRODUCTION AND PRESIDENTIAL PERIOD SUBJECT TITLES MANUSCRIPT DIVISION • REFERENCE DEPARTMENT LIBRARY OF CONGRESS WASHINGTON : 1972 Library of Congress 'Cataloging in Publication Data United States. Library of Congress. Manuscript Division. Index to the William Howard Taft papers. (Its Presidents' papers index series) 1. Taft, William Howard, Pres. U.S., 1857-1930. Manuscripts-Indexes. I. Title. II. Series. Z6616.T18U6 016.97391'2'0924 70-608096 ISBN 0-8444-0028-9 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Washington, D.C. 20402 - Price $24 per set. Sold in'sets only. Stock Number 3003-0010 Preface THIS INDEX to the William Howard Taft Papers is a direct result of the wish of the Congress and the President, as expressed by Public Law 85-147 approved August 16, 1957, and amended by Public Laws 87-263 approved September 21, 1961, and 88-299 approved April 27, 1964, to arrange, index, and microfilm the papers of the Presidents in the Library of Congress in order "to preserve their contents against destruction by war or other calamity," to make the Presidential Papers more "readily available for study and research," and to inspire informed patriotism. Presidents whose papers are in the Library are: George Washington James K. -

Martin Van Buren National Historic Site

M ARTIN VAN BUREN NATIONAL HISTORIC SITE ADMINISTRATIVE HISTORY, 1974-2006 SUZANNE JULIN NATIONAL PARK SERVICE U.S. DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR NORTHEAST REGION HISTORY PROGRAM JULY 2011 i Cover Illustration: Exterior Restoration of Lindenwald, c. 1980. Source: Martin Van Buren National Historic Site ii TABLE OF CONTENTS List of Illustrations vii Acknowledgements ix Introduction 1 Chapter One: Recognizing Lindenwald: The Establishment Of Martin Van Buren National Historic Site 5 Chapter Two: Toward 1982: The Race To The Van Buren Bicentennial 27 Chapter Three: Saving Lindenwald: Restoration, Preservation, Collections, and Planning, 1982-1987 55 Chapter Four: Finding Space: Facilities And Boundaries, 1982-1991 73 Chapter Five: Interpreting Martin Van Buren And Lindenwald, 1980-2000 93 Chapter Six: Finding Compromises: New Facilities And The Protection of Lindenwald, 1992-2006 111 Chapter Seven: New Possibilities: Planning, Interpretation and Boundary Expansion 2000-2006 127 Conclusion: Martin Van Buren National Historic Site Administrative History 143 Appendixes: Appendix A: Martin Van Buren National Historic Site Visitation, 1977-2005 145 Appendix B: Martin Van Buren National Historic Site Staffi ng 147 Appendix C: Martin Van Buren National Historic Site Studies, Reports, And Planning Documents 1936-2006 151 Bibliography 153 Index 159 v LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS Figure 1.1. Location of MAVA on Route 9H in Kinderhook, NY Figure 1.2. Portrait of the young Martin Van Buren by Henry Inman, circa 1840 Library of Congress Figure 1.3. Photograph of the elderly Martin Van Buren, between 1840 and 1862 Library of Congress Figure 1.4. James Leath and John Watson of the Columbia County Historical Society Photograph MAVA Collection Figure 2.1. -

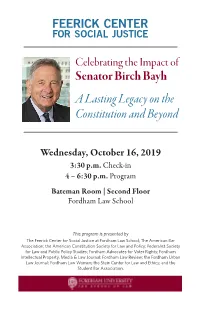

Senator Birch Bayh a Lasting Legacy on the Constitution and Beyond

Celebrating the Impact of Senator Birch Bayh A Lasting Legacy on the Constitution and Beyond Wednesday, October 16, 2019 3:30 p.m. Check-in 4 – 6:30 p.m. Program Bateman Room | Second Floor Fordham Law School This program is presented by The Feerick Center for Social Justice at Fordham Law School; The American Bar Association; the American Constitution Society for Law and Policy; Federalist Society for Law and Public Policy Studies; Fordham Advocates for Voter Rights; Fordham Intellectual Property, Media & Law Journal; Fordham Law Review; the Fordham Urban Law Journal; Fordham Law Women; the Stein Center for Law and Ethics; and the Student Bar Association. Agenda About the program This program will explore the legacy of Indiana Senator Birch 3:30 – 4 p.m. Bayh, the only person other than James Madison to draft Check-in more than one constitutional amendment. Four decades after he left the Senate, his achievements continue to reap benefits 4 – 4:50 p.m. and resonate in the national political discourse. Speakers Panel 1: Women’s Rights will focus on an array of Bayh’s accomplishments, including MODERATOR: Linda Klein, Past the 25th Amendment, the 26th Amendment, Title IX, the President, American Bar Assiciation proposed Equal Rights Amendment, the Bayh-Dole Act, PANELISTS: Stephanie Gaitley, Head and Senator Bayh’s nearly successful campaign to abolish the Women’s Basketball Coach, Fordham University; Billie Jean King, Tennis Electoral College. Fordham Law has a special history with Legend and Feminist Icon; Kelly Senator Bayh, which began when former dean and current Krauskopf, Assistant General Manager, professor John D. -

Kennedy Tops List of Democratic Contenders

The Harris Survey For Release: Thursday, July 3, 1975 - KENNEDY TOPS LIST OF DEMOCRATIC CONTENDERS BY LOUIS HARRIS Sen. Kennedy holds a wide lead over the 23 other potential Democratic nominees for the Presidential election. 1 A 31 percent plurality votes for Kennedy as first choice, and he is 16 percentage points ahead of his greatest competitor, Alabama Gov. Wallace. If Kennedy decides not to run, Wallace would move into first place with 18 percent, followed by Sen. Humphrey at 12 percent, Senators Hackson and Muskie at 10 percent each, and Sen. McGovern at 9 percent. Of the Democratic top runners, the only new faces to show any signs of rising strength are Ohio Sen,. Glenn and California Gov. Brown. But most of the possible Democratic candidates with any standing are old faces, which is ironic because more than seven in 10 voters have said they would like to vote for new and different politicians. The problem of most of the possible nominees is that they are relatively unknown. Sen. Bentsen, Rep. Udall, Wallace, Jackson, ex-Gov. Carter, ex-Gov. Sanford and ex-Sen. Fred Harris are still unknown to 49 percent of all likely Democratic and independent voters, and the collective vote for all of these hopefuls is no more than 26 percent. From June 4 to 10, the Harris Survey asked a cross section of 1,028 likely Democratic and independent voters: "Here is a list of people who have been mentioned as possible .nominees of the Democratic Party for President in 1976. (HAm RESPONDENT CARD) Now which one on that list would be your first choice for the nomination for President in 1976 if you had to choose right now?" With Kennedy In With Kennedy Out X X Sen. -

Julius CC Edelstein Papers, 1917-1961

Julius C. C. Edelstein Papers, 1917-1961 (Bulk Dates: 1948-1958) MS#1435 ©2008 Columbia University Library SUMMARY INFORMATION Creator Julius C. C. Edelstein, 1912-2005. Title and dates Julius C. C. Edelstein Papers, 1917-1961 (Bulk Dates: 1948-1958). Abstract Julius Caesar Claude Edelstein (1912-2005), served as advisor and executive assistant to military officials and political figures. His papers primarily encompass his job as executive assistant and chief of legislative staff to Senator Herbert H. Lehman during Lehman’s senatorial years 1949- 1956. Edelstein remained executive assistant to former senator Lehman from 1957-1960. His files include correspondence, memoranda, press releases, clippings, speeches, statistics, maps, pamphlets and government publications. Size 72.11 linear feet (135 document boxes and 33 index card boxes). Call number MS# 1435 Location Columbia University Butler Library, 6th Floor Julius C. C. Edelstein Papers Rare Book and Manuscript Library 535 West 114th Street New York, NY 10027 Language(s) of material Collection is predominantly in English; materials in Hebrew are indicated at folder level. Biographical Note Julius C. C. Edelstein was born in Milwaukee, Wisconsin on February 29, 1912. He studied at the University of Wisconsin in law and medicine, supporting himself through newspaper reporting. In 1937 he began working for the United Press covering US territories and island possessions. His career in journalism continued until World War II when he secured an ensign’s commission in the US Navy. After training as a communications officer, he became assistant naval aide to Admiral William D. Leahy, later being promoted to naval aide. Between 1945 and 1947 he served as public affairs advisor to the US High Commissioner to the Philippines, Paul V. -

Journal of Legal Technology Risk Management

THIRD CIRCUIT USES PROCEDURAL GROUNDS i JOURNAL OF LEGAL TECHNOLOGY RISK MANAGEMENT 1. THIRD CIRCUIT USES PROCEDURAL GROUNDS TO REJECT FCC’S WEAKENING OF MEDIA CROSS-OWNERSHIP RULES FOR A SECOND TIME IN PROMETHEUS RADIO PROJECT V. FCC 2. WHEN PARALLEL TRACKS CROSS: APPLICATION OF THE NEW INSIDER TRADING REGULATIONS UNDER DODD-FRANK DERAILS 3. ELECTRONIC DISCOVERY AND THE CONSTITUTION: INACCESSIBLE JUSTICE 4. RENEWING THE BAYH-DOLE ACT AS A DEFAULT RULE IN THE WAKE OF STANFORD V. ROCHE Volume 6 | Summer 2012 | Issue 1 (c) 2006-2012 Journal of Legal Technology Risk Management. All Rights Reserved. ISSN 1932-5584 (Print) | ISSN 1932-5592 (Online) | ISSN 1932-5606 (CD-ROM) www.ltrm.org II J. OF LEGAL TECH. AND RISK MGMT [Vol. 6 Editor-in-Chief Daniel B. Garrie, Esq. (USA) Guest Editor Kelly Merkel, Esq. (USA) Publications Editor Candice M. Lang, Esq. (USA) Executive Editors Matthew Armstrong, Esq. (USA) Dr. Sylvia Mercado Kierkegaard (Denmark) Scientific Council Stephanie A. “Tess” Blair, Esq. (USA) Hon. Amir Ali Majid (UK) Hon. Maureen Duffy-Lewis (USA) Micah Lemonik (USA) Andres Guadamuz (UK ) Carlos Rohrmann, Esq. (Brazil) Camille Andrews, Esq. (USA) Gary T. Marx (USA) William Burdett (USA) Eric A. Capriloi (France) Donald P. Harris (USA) Hon. Justice Ivor Archie (Trinidad & Tobago) ii Members Janet Coppins (USA) Eleni Kosta (Belgium) Dr. Paolo Balboni (Italy) Salvatore Scibetta, Esq. (USA) Ygal Saadoun (France/Egypt) Steve Williams, Esq. (USA) Rebecca Wong (United Kingdom) iii IV J. OF LEGAL TECH. AND RISK MGMT [Vol. 6 FOREWORD In this edition, we explore seemingly disparate realms of regulation and legislation and discover shared nuances in growing concern for current legal framework in all facets of legal practice and scholarship. -

The Political Career of Stephen W

37? N &/J /V z 7 PORTRAIT OF AN AGE: THE POLITICAL CAREER OF STEPHEN W. DORSEY, 1868-1889 DISSERTATION Presented to the Graduate Council of the North Texas State University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY By Sharon K. Lowry, M.A. Denton, Texas May, 19 80 @ Copyright by Sharon K. Lowry 1980 Lowry, Sharon K., Portrait of an Age: The Political Career of Stephen W. Dorsey, 1868-1889. Doctor of Philosophy (History), May, 1980, 447 pp., 6 tables, 1 map, bibliography, 194 titles. The political career of Stephen Dorsey provides a focus for much of the Gilded Age. Dorsey was involved in many significant events of the period. He was a carpetbagger during Reconstruction and played a major role in the Compromise of 1877. He was a leader of the Stalwart wing of the Republican party, and he managed Garfield's 1880 presidential campaign. The Star Route Frauds was one of the greatest scandals of a scandal-ridden era, and Dorsey was a central figure in these frauds. Dorsey tried to revive his political career in New Mexico after his acquittal in the Star Route Frauds, but his reputation never recovered from the notoriety he received at the hands of the star route prosecutors. Like many of his contemporaries in Gilded Age politics, Dorsey left no personal papers which might have assisted a biographer. Sources for this study included manuscripts in the Library of Congress and the New Mexico State Records Center and Archives in Santa Fe; this study also made use of newspapers, records in the National Archives, congressional investigations of Dorsey printed in the reports and documents of the House and Senate, and the transcripts of the star route trials. -

The Foreign Service Journal, May 1930

AMERICAN FOREIGN SERVICE JOURNAL Photo by Harris & Ewing. HOMER M. BYINGTON (See page 181) MAY, 1930 BANKING AND INVESTMENT SERVICE THROUGHOUT THE WORLD The National City Bank of New York and Affiliated Institutions THE NATIONAL CITY BANK OF NEW YORK CAPITAL, SURPLUS AND UNDIVIDED PROFITS $242,409,425.19 (AS OF MARCH 27, 1930) HEAD OFFICE FORTY ONE BRANCHES IN 55 WALL STREET. NEW YORK GREATER NEW YORK Foreign Branches in ARGENTINA . BELGIUM . BRAZIL . CHILE . CHINA . COLOMBIA . CUBA DOMINICAN REPUBLIC . ENGLAND . INDIA . ITALY . JAPAN . MEXICO . PERU . PHILIPPINE ISLANDS . PORTO RICO . REPUBLIC OF PANAMA . STRAITS SETTLEMENTS . URUGUAY . VENEZUELA. THE NATIONAL CITY BANK OF NEW YORK (FRANCE) S. A. Paris 41 BOULEVARD HAUSSMANN 44 AVENUE DES CHAMPS ELYSEES Nice: 6 JARDIN du Roi ALBERT ler INTERNATIONAL BANKING CORPORATION (OWNED BY THE NATIONAL CITY BANK OF NEW YORK) Head Office: 55 WALL STREET, NEW YORK Foreign and Domestic Branches in UNITED STATES . SPAIN . ENGLAND and Representatives in The National City Bank Chinese Branches BANQUE NATIONALE DE LA REPUBLIQUE D’HAITI (AFFILIATED WITH THE NATIONAL CITY BANK OF NEW YORK) Head Office: PORT AU-PRINCE, HAITI CITY BANK FARMERS TRUST COMPANY (AFFILIATED WITH THE NATIONAL CITY BANK OF NEW YORK) Head Office: 22 WILLIAM STREET, NEW YORK Temporary Headquarters: 43 EXCHANGE PLACE THE FOREIGN S JOURNAL PUBLISHED MONTHLY BY THE AMERICAN FOREIGN SERVICE ASSOCIATION VOL. VII, No. 5 WASHINGTON, D. C. MAY, 1930 A Pilgrim’s Sea Shell By AUGUSTIN \Y. PERU IN, Consul, Department MANY persons in the Department have fortunately discovered that the body of St. James asked me why I wear a clamshell in my the Apostle was interred at Compostela in Spain. -

Bayh-Dole-Sign-On-Letter | AUTM

712 H Street NE Suite 1611 Washington DC 20002 +1.202.960.1800 April 5, 2021 Secretary Gina Raimondo U.S. Department of Commerce 1401 Constitution Avenue NW Washington, DC 20230 James K. Olthoff Acting Under Secretary of Commerce for Standards and Technology National Institute of Standards and Technology 100 Bureau Drive Gaithersburg, MD 20899 Eric S. Lander Director, Office of Science and Technology Policy The White House 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue NW Washington, DC 20006 Dear Secretary Raimondo, Dr. Olthoff, and Dr. Lander, In 1980, lawmakers passed the groundbreaking Bayh-Dole Act and ignited four-plus decades of American innovation. The bipartisan law enabled universities and non-profit institutions to secure patent rights on government-funded breakthroughs. Before the Act, there was no simple path from academic laboratory to consumer. By encouraging technology transfer from universities to the private sector, this seemingly simple reform laid the groundwork for extraordinary economic growth. As past Presidents/Chairs of AUTM, the leading organization of technology-transfer professionals, we strongly support maintaining and improving the Bayh-Dole Act. To that end, AUTM supports the current proposal from the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) to clarify the original intent of the law. Since 1996, Bayh-Dole has led to the creation of more than 14,000 start-ups1 in fields ranging from agriculture to software to biotech. It dramatically accelerated biopharmaceutical innovation, contributing to the development of nearly 300 new drugs and vaccines.2 Products like Honeycrisp apples34 and high-definition televisions56 to services like Google’s search engine7 include the Bayh-Dole Act in their origin stories.8 Beyond inventions like these, between 1996 and 2017 Bayh-Dole contributed up to $865 billion to U.S. -

The Elder Brewster of Pennsylvania

Volume 41 Issue 2 Dickinson Law Review - Volume 41, 1936-1937 1-1-1937 The Elder Brewster of Pennsylvania Lewis C. Cassidy Follow this and additional works at: https://ideas.dickinsonlaw.psu.edu/dlra Recommended Citation Lewis C. Cassidy, The Elder Brewster of Pennsylvania, 41 DICK. L. REV. 103 (1937). Available at: https://ideas.dickinsonlaw.psu.edu/dlra/vol41/iss2/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Reviews at Dickinson Law IDEAS. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dickinson Law Review by an authorized editor of Dickinson Law IDEAS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE ELDER BREWSTER OF PENNSYLVANIA LEWIS C. CASSIDY* The Pennsylvania bar of the nineteenth century was for that long period the most distinguished bar in the United States. Its history has never been written but there is a wealth of material from which it might be fashioned. Such a history can not be written apart from the epochal changes in the social, economic and po- litical structure of the state and of the nation. This interrelation was apparent in the writings of Alexander K. McClure, Samuel W. Pennypacker and Hampton L. Carson, and their approach to the subject was legal, historical and political. Five periods are discernible in the history of the Pennsylvania bar: 1. The era of the American Revolution, of Edward Shippen, Andrew Hamilton, the elder William Rawle and James Wilson; 2. The Jacksonian era of George M. Dallas, John B. Gibson, Horace Binney, John Sergeant and David Paul Brown; 3. The Civil War era of Jeremiah Sullivan Black, William M.