Information to Users

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

570259Bk USA 15/5/07 8:15 Pm Page 5

570259bk USA 15/5/07 8:15 pm Page 5 Slovak Radio Symphony Orchestra The Slovak Radio Symphony Orchestra was founded in 1929 as the first professional musical ensemble fulfilling the needs of radio broadcasting in Slovakia. The first conductors already placed particular emphasis on contemporary Slovak music in their programmes, resulting in a close connection with leading Slovak composers, BLOCH including Alexander Moyzes, Eugen SuchoÀ, Ján Cikker and others. The original ensemble was gradually enlarged and from 1942, thanks to Alexander Moyzes, the then Director of Music in Slovak Radio, regular symphony concerts were given, broadcast live by Slovak Radio. From 1943 to 1946 the Yugoslavian Kre‰imír Baranoviã was Four Episodes • Two Poems the chief conductor of the orchestra, to which he made a vital contribution. His successors were ªudovít Rajter, Ladislav Slovák, Václav Jiráãek, Otakar Trhlík, Bystrík ReÏucha and Ondrej Lenárd, whose successful Concertino • Suite Modale performances and recordings from 1977 to 1990 helped the orchestra to establish itself as an internationally known concert ensemble. His successor Róbert Stankovsky continued this work, until his unexpected death at the age of Noam Buchman, Flute • Yuri Gandelsman, Viola 36. Charles Olivieri-Munroe held the position of chief conductor from 2001-2003, with the current principal guest conductor Kirk Trevor. Oliver von Dohnányi was appointed chief conductor of the orchestra in 2006, and regular Soloists of the Israel Philharmonic Orchestra live concerts have continued also under the new second conductor Mario Kosik. Through its broadcasts and many recordings the orchestra has also become a part of concert life abroad, with successful tours to Austria, Italy, Slovak Radio Symphony Germany, The Netherlands, France, Bulgaria, Spain, Japan, Great Britain and Malta. -

4932 Appendices Only for Online.Indd

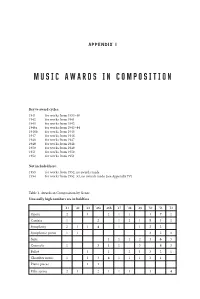

APPENDIX I MUSIC AWARDS IN COMPOSITION Key to award cycles: 1941 for works from 1934–40 1942 for works from 1941 1943 for works from 1942 1946a for works from 1943–44 1946b for works from 1945 1947 for works from 1946 1948 for works from 1947 1949 for works from 1948 1950 for works from 1949 1951 for works from 1950 1952 for works from 1951 Not included here: 1953 for works from 1952, no awards made 1954 for works from 1952–53, no awards made (see Appendix IV) Table 1. Awards in Composition by Genre Unusually high numbers are in boldface ’41 ’42 ’43 ’46a ’46b ’47 ’48 ’49 ’50 ’51 ’52 Opera2121117 2 Cantata 1 2 1 2 1 5 32 Symphony 2 1 1 4 1122 Symphonic poem 1 1 3 2 3 Suite 111216 3 Concerto 1 3 1 1 3 4 3 Ballet 1 1 21321 Chamber music 1 1 3 4 11131 Piano pieces 1 1 Film scores 21 2111 1 4 APPENDIX I MUSIC AWARDS IN COMPOSITION Songs 2121121 6 3 Art songs 1 2 Marches 1 Incidental music 1 Folk instruments 111 Table 2. Composers in Alphabetical Order Surnames are given in the most common transliteration (e.g. as in Wikipedia); first names are mostly given in the familiar anglicized form. Name Alternative Spellings/ Dates Class and Year Notes Transliterations of Awards 1. Afanasyev, Leonid 1921–1995 III, 1952 2. Aleksandrov, 1883–1946 I, 1942 see performers list Alexander for a further award (Appendix II) 3. Aleksandrov, 1888–1982 II, 1951 Anatoly 4. -

Program Trio in C Major, No

Long Theater * Stockton, California * March 31, 1979 * 8:00 p.m. FRIENDS OF CHAMBER MUSIC in cooperation with UNIVERSITY OF THE PACIFIC, and SAN JOAQUIN DELTA COLLEGE present Bruno Canino, piano Cesare Ferraresi, violin Rocco Filippini, cello PROGRAM TRIO IN C MAJOR, NO. 43 (HOBOKEN XV NO. 27) • (Franz) Joseph Haydn (1732 - 1809) Allegro Andante Finale (Presto) TRIO IN A MINOR (1915) . ... Maurice Ravel Modere (1875 - 1937) Pantoum (Assez vif) Passacaille (Tres large) Final (Anime) INTERMISSION TRIO IN B FLAT MAJOR, OPe 97 •• ..... Ludwig ("The Archduke") van Beethoven Allegro moderado (1770 - 1827) Scherzo (Allegro) Andante cantabile, rna pero con moto (Variations) Allegro moderato - Presto Trio di Milano is represented by Mariedi Anders Artists Manage ment, Inc., 535 El Camino Del Mar, San Francisco, California. The TRIO DI MILANO, composed of three noted and talented musicians, was formed in the spring of 1968. Engaged by the most important Italian musical societies to play at Milan, Torino, Venice, Rome, Florence, Pisa, Genoa, and Padua, the Trio has also performed in Germany, Switzerland, Spain, Portugal and the United States and has been acclaimed with enthu siasm and exceptional success everywhere. CESARE FERRARESI was born at Ferrara in 1918, took his degree for violin at the Verdi Conservatorio of Milan, where he is now Principle Professor. Winner of the Paganini Prize and of the International Compe tition at Geneva, he has now for many years enjoyed an intensely full and busy career as a concert artist. Leader of the Radio Symphony Orchestra (RAI) at Milan and soloist of the "Virtuosi di Roma", he has played at the most important music festivals at Edinburgh, Venice, Vienna, and Salz burg and in the major musical centers of Europe, Japan, and the United States. -

20Th-Century Repertory

Mikrokosmos List 667. - 2 - March 2021 ....20TH-CENTURY REPERTORY 1 Amram: Triple Con for Woodwinds, Brass, Jazz Quintets & Orch, Elegy for Vln & FLYING FIS GRO 751 A 8 Orch - Amram Jazz Q, Weiss vln, cond.Zinman (p.1978) S 2 Arnold: Cl Sonatina/Horovitz: Cl Sonatina/Ireland: Fantasy Sonata/Finzi: CHANDOS ABRD 1237 A 10 Bagatelles/A.Richardson: Roundelay/P.Harvey: Gershwin Suite - G.de Peyer cl, G.Pryor pno (p.1987) S 3 Auric, Georges: Fontaine de Jouvence Suite, Malborough ballet (Paris PO, RENAISSANC X 41 A 12 cond.Leibowitz)/P.Gradwohl: Divertissement Champetre (Conservatoire Orch, cond.comp) 4 Babajanian: Heroic Ballad (comp.pno, USSR RSO, Rachlin)/ Tchaikovsky: Concert CLASSIC ED CE 7 A 10 Fant (Nikolayeva, USSR SSO, Kondrashin) 5 Balassa: The Third Planet opera - Misura, Takacs, Gregor, cond. A.Ligeti (p.dig, HUNGAROT SLPD 31186 A 12 1990) S 6 Barber: Sym 1, School for Scandal Ov, Medea Suite, Adagio - Eastman-Rochester MERCURY SRI(HP) 75012 A 8 Orch, cond.Hanson S 7 Bartos, J.Z: Vln Con (Lustigova, cond.Stejskal); Duo for Vln & Vla (Tomasek, PANTON 110429 A 8 Simacek); Cerny (Jindrak bar, Mencl pno) 1974 S 8 Bliss: Pno Con, March of Homage, Welcome the Queen - Fowke pno, cond.Atherton UNICORN DKP 9006 A 8 1980 S 9 Bliss: Serenade, Hymn to Aplollo, A Prayer, etc - cond.comp, etc (Decca pressing) LYRITA SRCS. 55 A 8 (p.1971) S 10 Bloch: Concerto grossi 1, 2 - Eastman Rochester Orch, cond.Hanson S MERCURY SRI(HP) 75017 A 8 11 Borkovec: Pno Con 1 (Panenka, Czech PO, cond.Kosler)/Schulhoff: Pno Con 2 SUPRAPHON 1101205 A++ 8 (Baloghova, -

Disc and Tape Reviews

Miss Licad began her mu- For an account of Miss Von With the retirement of Glenn sical studies in the Philippines Stade's latest operatic record- Gould from the concert stage, and continued them at the Cur- ing, see the review of Montever- Silverman is probably Canada's tis Institute in Philadelphia, di's// Ritorno d'Uhsse in Patria pre-eminent "live"pianist. He where she studied for five years on the next page. Her recent plays regularly with the major withRudolfSerkin,Seymour CBS album of French songs Canadian orchestras, he Lipkin,and Mieczyslav Hors- with the Boston Symphony un- teachesattheUniversityof zowski. In addition to a $10,000 der Seiji Ozawa will be reviewed Vancouver, he broadcasts for prize, the Leventritt award in- here next month. 0 the CBC. "Being Canadian is cludes appearances withthe not lust a physical thing," he world'sforemostorchestras says, "but a state of mindAll over a three-year period, begin- THE Moss Music Group has my records are on American la- ning in September 1981 with the signed a licensing agree- bels because there really is no New York Philharmonic under ment with the Soviet Melodiya Canadian classical company. Zubin Mehta.MissLiced is label which will give MM3 first - That'satangiblething But about to sign a recording con- refusalrights in the United there is also this attitude that if tract with CBS Masterworks, so States and Canada on all Me- it's Canadian it can't be much we should all be able to hear lodiya products. In pas' years good,andmost Canadians her soon. -

20Th-Century Repertory

Mikrokosmos List 626. - 2 - October 2017 ....20TH-CENTURY REPERTORY 1 Akhinyan: Sym 1/Khudoyan: Vcl Con 2 - Abramyan vcl, cond.Mangasaryan S MELODIYA C10 7549 A 18 2 Akhmetov: Sym 1; Tatarstan Ov - cond.Mansurov, Salavatov 1983 S MELODIYA C10 20503 A 60 3 Aladov, Nicolai: Sym 10 - Byelorus SSO, cond.A.Engelbrecht 1981 S MELODIYA C10 16451 A 65 4 Alfven: Elegi, Midsommarvaka/Svendsen: Carneval in Paris/Nielsen: WORLD OF M KBO 1003 A- 10 Hanedans/SibeliusRomans in C - Covent Garden OpOrch, cond.Hollingsworth (jacket worn a bit) 5 Ali-Zade: Chamber Sym, Rustic Suite, 2 Miniatures - cond.Korneyev, Niyazi S MELODIYA C10 9473 A 20 6 Andriessen, Louis: Hoketus/ F.Rzewski: Coming Together - Hoketius Ens 1979 S HOKETUS 1 A 30 7 Arrieu, Claude: 5 Movements/P-M.Dubois: Quatour/Vivaldi-Lancelot: CORELIA CC 83413 A 20 Quartet/Albinoni-Thilde: Sonata in c - Rouen Cl Quartet (p.1983) S 8 Arutiunian: Cantata for Our Land (Arkhipova, Klenov, Fedoseyev); Theme & Vars; MELODIYA C10 10735 A 15 Festival Ov (cond.Mangasarian) S 9 Ashrafi: Mukhabbat ballet excs - Uzbek Navoi Bolshoi Thetre Orch, cond.comp MELODIYA M30 35923 A 30 10 Bacarisse: Guitar Con in a/Torroba: Homenaje a la Seguidilla - N.Yepes gui, GENIOS DE GML 2011 A 15 Spanish FO, cond.Fruhbeck de Burgos S 11 Badings: Reeks kleine klankstukken, Son 3 for 2 Vlns/A.de Beer: Instructieve STICHTING RC 227 A 15 onatine/H.Kox: Serenade for 2 Vlns/Vitali: Son a tre/Sweelinck: Paduana Lachrimae - Lemkes, Vos vln S 12 Baird: Jutro - Szostek-Radkova, Artysz, Pawlak, Ostrowski, cond.Czajkowski MUZA SX 1057 A 8 (gatefold) S 13 Barraque: .. -

Armenian State Quartet Borodin / Shostakovich String Quartets Mp3, Flac, Wma

Armenian State Quartet Borodin / Shostakovich String Quartets mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Classical Album: Borodin / Shostakovich String Quartets Country: UK Style: Modern, Romantic MP3 version RAR size: 1884 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1583 mb WMA version RAR size: 1558 mb Rating: 4.7 Votes: 885 Other Formats: ASF MP4 XM WMA AAC AA DXD Tracklist Hide Credits Quartet No. 2 In D Major Composed By – Alexander Borodin A1 Allegro moderato A2 Scherzo A3 Notturno A4 Finale (Andante) Quartet No. 1, Op. 49 Composed By – Dmitri Shostakovich B1 Moderato B2 Moderato B3 Allegro molto B4 Allegro Companies, etc. Record Company – Electric & Musical Industries (U.S.) Ltd. Credits Cello – Sergei Aslamazyan* Viola – Genrikh Talalyan* Violin – Avet Ter-Gabrielyan, Rafael Davidyan Notes Album is credited to Armenian State Quartet with Komitas Quartet in parentheses. Inner sleeve is fragile wax paper with Made In England printed on both sides. Related Music albums to Borodin / Shostakovich String Quartets by Armenian State Quartet Borodin & Prokofiev - Prague Quartet - 2 String Quartets Dmitri Shostakovich, The Beethoven Quartet, The Comitas Quartet - Quartet No 12 For Two Violins, Viola And Cello In D Flat Major, Op. 133 / Quartet No 11 For Two Violins, Viola And Cello In F Minor, Op. 122 / Two Pieces For String Octet Op. 11 Shostakovich – The Shostakovich Quartet - Complete String Quartets Shostakovich / Borodin Quartet (Original Members) - String Quartets 1 - 13 The Vaghy String Quartet - Shostakovich / Szymanowski - String Quartet No. 8 / String Quartet No. 2, Op. 56 Dmitri Shostakovich : Borodin Quartet / Richter - String Quartet No. 3, Two Pieces For String Octet, Piano Quintet Квартет Имени Бородина - Д. -

Aram & Karen Khachaturian

95357 ARAM & KAREN KHACHATURIAN Music for Violin and Piano Ruben Kosemyan violin · Natalya Mnatsakanyan piano Karen Khachaturian 1920-2011 · Aram Khachaturian 1903-1987 Karen Khachaturian (1920-2011) is considered one of the most notable composers of Armenia. He was the nephew of the composer Aram Khachaturian. Each of his works clearly demonstrates an unerring feeling for musical form and Karen Khachaturian structure and a keen ear for timbre and harmony. In addition to the Violin Sonata Violin Sonata in G minor Op.1 (1947) (1947), his works include a Cello Sonata (1966), a String Quartet (1969), four 1. Allegro 5’42 symphonies (1955, 1968, 1982, 1991) and a ballet “Cipollino” (1973), as well as 2. Andante 4’04 various other orchestral works and music for the theatre and films. 3. Presto 5’00 Karen Khachaturian’s Sonata for violin and piano (1947) brought him international attention. Rhythmic drive and an idiomatic use of the instrumental forces characterize this attractive and colourful work. Aram Khachaturian 4. “ Sabre Dance” from “Gayane” ballet (transcription by J. Heifetz) 2’17 5. “Dance” 4’24 6. “ Lullaby” from “Gayane” ballet 3’20 7. “ Ayesha’s Dance” from “Gayane” ballet (transcription by J. Heifetz) 2’19 8. “ Song-Poem” (in Honor of Ashugs) arranged by R. Kosemyan 6’17 9. “ Adagio” from “Spartacus” ballet (transcription by H. Smbatyan) 6’46 10. “ Andante Sostenuto” from violin concerto 10’10 Ruben Kosemyan violin · Natalya Mnatsakanyan piano Recording: October 2017, “Composers Union of Armenia” Sound engineer: Sergey Gasparyan Photos by H. Karapetyan and B. Khachaturyan Cover: Laguna Landscape, by Joseph Kleitsch (Oil On Canvas, 1925) p & © 2018 Brilliant Classics Ruben Kosemyan (left) & Karen Khachaturian (right) 2 3 Aram Khachaturian (1903-1978) was the most famous Armenian composer of the Aram Khachaturian's 20th century and the author of ballet music, symphonies, concertos, and film scores. -

Modified String Quartet Practices in Post-Soviet Eurasia" (2013)

Western Michigan University ScholarWorks at WMU Master's Theses Graduate College 6-2013 A New Kind of National: Modified String Quartet Practices in Post- Soviet Eurasia Adam Taylor Lenz Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/masters_theses Part of the Composition Commons, Ethnomusicology Commons, and the Musicology Commons Recommended Citation Lenz, Adam Taylor, "A New Kind of National: Modified String Quartet Practices in Post-Soviet Eurasia" (2013). Master's Theses. 162. https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/masters_theses/162 This Masters Thesis-Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate College at ScholarWorks at WMU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at WMU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A NEW KIND OF NATIONAL: MODIFIED STRING QUARTET PRACTICES IN POST-SOVIET EURASIA by Adam Taylor Lenz A thesis submitted to the Graduate College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts School of Music Western Michigan University June 2013 Thesis Committee: Matthew Steel, Ph.D., Chair David Loberg Code, Ph.D. Christopher Biggs, D.M.A. ! A NEW KIND OF NATIONAL: MODIFIED STRING QUARTET PRACTICES IN POST-SOVIET EURASIA Adam Taylor Lenz, M.A. Western Michigan University, 2013 This thesis examines the practices of string quartet modification implemented by three post-Soviet Eurasian composers: Franghiz Ali-Zadeh (Azerbaijan), Vache Sharafyan (Armenia), and Dmitri Yanov-Yanovsky (Uzbekistan). After an introduction to the geography of the region and the biographies of the composers, their works containing modified string quartet configurations are examined within three distinct modification practices. -

Boll. Tosc. Giugno 2006

2 UNA FANCIULLA CENTENARIA Cari Amici, dicembre. Sul podio Filippo Maria Bressan, affiancato dal giovane e formidabile clarinettista la Fanciulla del West di Giacomo Puccini svedese Martin Fröst nel Concerto in la maggio- compie cent’anni dalla sua prima esecuzione re K. 622 di Mozart. Il Concerto di Natale newyorkese. Per ricordare questa importante dell’Orchestra della Toscana, con il Coro del ricorrenza, Rete Toscana Classica dedica all’ope- Maggio Musicale Fiorentino impegnato nella ra «western» un approfondimento in tre trasmis- Deutsche Messe di Schubert e nella Messa di sioni, in cui la musicologa Barbara Boganini Puccini, sarà trasmesso in differita il 26 dicem- svela i frutti delle sue ricerche sulle fonti ameri- bre. Sul podio lo specialista pucciniano Giuliano cane utilizzate da Puccini e propone una ricostru- Carella. zione della magica serata al Maggio Musicale Come da tradizione, in quest’ultimo mese del Fiorentino del 1954, quando Dimitri Mitropoulos 2010 potrete ascoltare un’ampia scelta di musi- rivelò con inequivocabile perentorietà interpreta- che composte per il Natale dal medioevo a oggi. tiva la grandezza sinfonica di questa partitura di Quest’anno, l’edizione prescelta dell’Oratorio di Puccini per molti aspetti sperimentale. Al suo Natale di Bach, distribuito su sei giornate dal 25 fianco aveva uno spaesato Curzio Malaparte in dicembre all’Epifania secondo la destinazione veste di regista e il pennello di Ardengo Soffici liturgica originale, è quella del complesso ingle- nell’inedita veste di scenografo. Le trasmissioni, se The Sixteen diretto da Harry Christophers. avviate nell’ultima settimana di novembre, cul- mineranno il 10 dicembre (data del centenario) Vi auguriamo di trovare con Rete Toscana dall’ascolto integrale della registrazione dal vivo Classica il miglior corredo sonoro alle Festività dell’esecuzione fiorentina, con Eleanor Steber, natalizie, che auspichiamo serene per tutti. -

Mikrokosmos Labelography

Mikrokosmos List 579. - 2 - October 2013 ....MIKROKOSMOS LABELOGRAPHY 1 Mikrokosmos Labelography Vol.1+2: 240 color labels with specially designed MIKROKOSMO VOL. 12 A++ 78 plastic folders and binder (Decca, EMI, Melodiya, Mercury, RCA, etc) 2 Mikrokosmos Labelography Vol.3-4: Additional 192 color labels with specially MIKROKOSMO VOL. 34 A++ 58 designed plastic folders (Decca, EMI, Melodiya, Mercury, RCA) 3 Mikrokosmos Labelography Vol.5-6: Additional 192 color labels with specially MIKROKOSMO VOL. 56 A++ 68 designed plastic folders (Ducretet-Thomson, Decca, EMI, etc) (postage at www.mikrokosmos.com/labelography.asp) ....20TH-CENTURY REPERTORY 4 Adams, John Luther: Forest Without Leaves - Arctic ChO & Ch, cond.McGilvray OWL 32 A 10 (1987) S 5 Adams, John: Grand Pianola Music/ S.Reich: 8 Lines - Solisti New York, cond.Wilson ANGEL DS 37345 A 10 S 6 Adams, John: The Wound-Dresser; Fearful Symmetries - Sylvan bar, Orch of St NONESUCH 9 79218 A 18 Luke's, cond.comp S 7 Alexandrov, Anatoly: Levsha opera - Glubokov, Ovchinnikov, Gulyayev, MELODIYA C50 9969 A 12 cond.Herskovich S 8 Arvay, Pierre: Sonate/Koechlin: Chant de serenite/Samazeuilh: Luciole/Michael, TEPPAZ 245001 A 50 Eduard: Elegie/Jolivet: Serimpie (all for ondes martenot & pno) - N.Caron om, G.Boyer pno 10" 9 Bacewicz: Musica Sinfonica, Pensieri Notturni, Con for Orch, Overture - cond.Rowicki MUZA XL 274 A 10 10 Bacewicz: Quartet for vcls/Lutoslawski: Postlude/Boguslawski: Intonations - MUZA W 969 A 30 cond.Krenz, Stryja Warsaw Autumn, 1964 (minor jacket damage) 10" 11 Baird, Tadeusz: -

COLINJACOBSEN,™>\M BRUCE LEVINGSTON,Piano Mosic FJ^OM

ncerts fror/f the libro^y of congress 2010-2011 CL The McKim Fund -& The Carolyn Roy all Just Fund in the Library of Congress COLIN JACOBSEN, ™>\m BRUCE LEVINGSTON, piano Mosic FJ^OM Moscow TIGRAN ALIKHANOV, M Friday, May 6,2011 Friday, May 13, 2011 8 o'clock in the evening Coolidge Auditorium Thomas Jefferson Building The McKiM FUND in the Library of Congress was created in 1970 through a bequest of Mrs. W. Duncan McKim, concert violinist, who won international prominence under her maiden name, Leonora Jackson, to support the commissioning and performance of chamber music for violin and piano. The CAROLYN ROYALL JUST FUND in the Library of Congress, established in 1993 through a bequest of the distinguished attorney and symphony player Carolyn Royall Just, supports the presentation and broadcasting of classical chamber music concerts. The audiovisual recording equipment in the Coolidge Auditorium was endowed in part by the Ira and Leonore Gershwin Fund in the Library of Congress. Request ASL and ADA accommodations five days in advance of the concert at 202-707-6362 [email protected]. Due to the Library's security procedures, patrons are strongly urged to arrive thirty min- utes before the start of the concert. Latecomers will be seated at a time determined by the artists for each concert. Children must be at least seven years old for admittance to the chamber music con- certs. Other events are open to all ages. Reserved tickets not claimed by five minutes before the beginning of the event will be distributed to standby patrons. Please take note: UNAUTHORIZED USE OF PHOTOGRAPHIC AND SOUND RECORDING EQUIPMENT IS STRICTLY PROHIBITED.