Final Report for Data Collection and Confirmation Study for Agricultural Value Chains in the Republic of India

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

District Census Handbook, Nizamabad, Part II

CENSUS OF INDIA, 1951 HYDERABAD STATE District Ce11sus Handbook NIZAMABAD DISTRICT PART II Issued by BUREAU OF ECONOMICS AND STATISTICS FINANCE DEPARTMENT GOVERNMENT OF HYDERABAD PRICE Rs. 4 NIZAMABAD DISTRICT NIZAMABAD DISTRICT HYDERABAD STATE SCALE 1 INCH = 16 MILES ADfLABAD OISTRICl ~\~"'~ -(0 TO JAGTI't4L \ \ . ...... ! /' KARIMNAGAR DISTRICT ¢ I . ( i \ . /,.~ ....... \ .-t. .,. ...... ./ I . "'~ .. ~p'a .~ ....~\'" -(0 TO . (' ."'> ~o·-· SIDAR DISTRICT "Y)- .,~ -9.., c9~<) , MEDAK OISTRICT REFERENCES .. .. 1)ISTR1CT BOUNDAR'l _ _ _ TALUQ DO ._ ._._._ 'DISTRlCT HEAOQUARTER TALUQ DO o RAILWAV M. G. ROAD RIVER PREPARED BY THE SETTLEMENT &. LAND RECORDS DePT. CONTENTS PAGE MAP OF NIZ4.MABAD DISTRICT Fronti8piece Preface v Explanatory Note on Tables 1 List of Census Tracts-Nizamabad District 5 1. GENERAL POPuLATION TABLES Table A- I-AI'ea, Houses and Population 6 Table A· II-Variation in Population during Fifty Years .. S Table A-III-Towns and Villages Classified by Population lO Table A-IV-Towns Classified by Population with Variations sinee 1901 12 Tl;lble A- V-Towns an:'anged Territorially with Population by Livelihood Classes 14 2. ECONOMIC 'fABLES Table B· I-Liveli!lOod Classes and Sub-Classes 16 Table B-n-~e('ondary Means of Livelihood 22 3. SOCIAL AND CULTURAL TABLES Table D-I (i) Languages-Mother Tongue ' .. 26 Table D-I (ii) Languag2s-BilinguaJism 28 Table D- II-Religion. 82 Table D- III-Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes ,84 Table D- VII-Litern.cy hy Educational Standards ... 36 4. GENERAL SUMMARY TABLE Table E Summ'lry Figures by Ta.hsils a8 5. PRIMARY CENSUS ABSTRACTS (i) Rural Statistics MAP OF NIZAMABAD TAHSIL Prim[1l'y Census Abslract-Nizamabad Tahsil Rural .• 41 MAP OF KAMAREDDY TAHSIL Prillnry C(>l1SUS Ahstract-Kamareddy Tahsil Rural •• .5a_ iii PAGE MAp OF YELLAREDDY TAHSIL Primary Census Abstract-Y ellareddy Tahsil Rura] . -

National Institute of Rural Development and Panchayati Raj Newsletter No

National Institute of Rural Development and Panchayati Raj Newsletter www.nird.org.in No. 235-236 December 2014-January 2015 NIRD&PR Newsletter DECEMBER 2014-JANUARY 2015 Cover Story Skill Development for Rural Youth Initiatives and Perspectives 430 million people in our country are in the age group 15-34 and constitute 35% of the population (Census 2011). This age group is projected to increase to 464 million by 2021. This can result in a “demographic dividend” for India if the capabilities of the youth are also developed.However, considering the present status of the workforce in terms of educational attainment and skill training, this is a big challenge. If the challenge is overcome by investing adequately in Programmes were revamped and and reprioritised to build the capacity their education and employability, this merged into a holistic self- of rural poor youth to address the need youth power has the potential to employment scheme called transform the Indian economy. of domestic and global skills Swarnjayanti Gram Swarozgar requirement. The focus is on skilling It is in the above context, skill Yojana (SGSY). It graduated in 2004 and placement in the formal sector so development and self-employment to Swarnjayanti Gram Swarozgar as to provide youth with jobs having programmes have been part of the Yojana (SGSY)- Special Projects. This regular monthly wages at or above the initiatives for rural development. The programme was revisited in the light minimum wages. In the approach of of the new Skills framework and programmes of Ministry of Rural the Scheme, the shift is in emphasis- repositioned as Aajeevika Skills. -

Self-Sufficient Villages: Cases of Southern Region of India

6 V May 2018 http://doi.org/10.22214/ijraset.2018.5469 International Journal for Research in Applied Science & Engineering Technology (IJRASET) ISSN: 2321-9653; IC Value: 45.98; SJ Impact Factor: 6.887 Volume 6 Issue V, May 2018- Available at www.ijraset.com Self-Sufficient Villages: Cases of Southern Region of India Dr. Pallavi Sharma1 1Amity School of Architecture and Planning, Amity University Haryana Abstract: We are directed as well indirectly benefitted from nature, it is impossible for us to survive without it. We know that, a large number of medicines that we use and the foods we get from plants and animals. There are some many things which we can learn from nature and can be used for our future science and technology. Progress is directly related to nature. If we want our progress to be fast then we can copy nature. There are many examples which clearly show how nature helps us in our day to day life. By studying polar bear's fur, we can get to know about better insulation, the design of helicopter resembles bee, firefly depicts light. etc. The major cause to nature done by the lifestyles we have adopted. As we are impatient and always want to change things according to our choice, we inefficiently use natural resources. Our preference has changed from natural tapestry to technology. We should not exploit naturally available resources like oil and gas which takes years of time to produce, we should invent technologies which are innovative. This includes biogas produced biomass; efficient biomass producing electricity and fuel for kitchen, wind turbines can be used, solar panels can extract energy from the sun and can be converted into electricity. -

Property Registration to Resume After 2 Months

Follow us on: @TheDailyPioneer facebook.com/dailypioneer RNI No. TELENG/2018/76469 Established 1864 ANALYSIS 7 MONEY 8 SPORTS 12 Published From HYDERABAD DELHI LUCKNOW DRAGON COVID DOWNTURN TO BE DEEPER MI CLOSE IN ON BHOPAL RAIPUR CHANDIGARH UNSCATHED IN SINGAPORE PLAYOFF SPOT BHUBANESWAR RANCHI DEHRADUN VIJAYAWADA *LATE CITY VOL. 3 ISSUE 13 HYDERABAD, THURSDAY OCTOBER 29, 2020; PAGES 12 `3 *Air Surcharge Extra if Applicable PAWAN KALYAN TO SWING INTO ACTION STRAIGHTAWAY { Page 11 } www.dailypioneer.com UNION MINISTER SMRITI IRANI DELHI UNIVERSITY VC SUSPENDED TPCC RULES OUT VIJAYASHANTI US SELF-STYLED GURU, GUILTY OF TESTS POSITIVE FOR CORONAVIRUS BY PRESIDENT OVER ‘MISCONDUCT’ QUITTING CONGRESS PARTY LEADING SEX CULT JAILED FOR 120 YRS nion Minister Smriti Irani has tested positive for he Vice Chancellor of the University of Delhi, Yogesh Tyagi, has been ollowing a "courtesy call" on Telangana Pradesh "self-help" guru convicted of running a cult-like organization of sex slaves Ucoronavirus, she tweeted on Wednesday. It is rare Tsuspended on President Ram Nath Kovind's orders amid a controversy FCongress Committee campaign committee Awho were branded with his initials was sentenced to for me to search for words while making an over appointments, the union education ministry said on chairperson Vijayashanti, TPCC working president 120 years in prison by a New York judge Tuesday. The announcement; hence here's me keeping it simple - Wednesday. The education ministry had asked the President Kusuma Kumar said that she would not quit the effective life sentence for Keith Raniere, 60, comes I've tested positive for #COVID and would request to allow inquiry against the vice chancellor after a dispute Congress. -

State District Branch Address Centre Ifsc

STATE DISTRICT BRANCH ADDRESS CENTRE IFSC CONTACT1 CONTACT2 CONTACT3 MICR_CODE A.N.REDDY NAGAR ANDHRA A N REDDY BR,NIRMAL,ANDHRA PRADESH ADILABAD NAGAR PRADESH NIRMAL ANDB0001972 8734243159 NONMICR 3-2-29/18D, 1ST CH.NAGAB FLOOR, AMBEDKAR HUSHANA ANDHRA CHOWK ADILABAD - M 08732- PRADESH ADILABAD ADILABAD 504 001 ADILABAD ANDB0000022 230766 TARA COMPLEX,MAIN ANDHRA ROAD,ASIFABAD,ADI 08733 PRADESH ADILABAD ASIFABAD LABAD DT - 504293 ASIFABAD ANDB0002010 279211 504011293 TEMPLE STREET, BASARA ADILABAD, ANDHRA ADILABAD, ANDHRA 986613998 PRADESH ADILABAD BASARA PRADESH-504104 BASAR ANDB0001485 1 Bazar Area, Bellampally , Adilabad G.Jeevan Reddy ANDHRA Dist - - 08735- PRADESH ADILABAD Bellampalli Bellampalli ADILABAD ANDB0000068 504251 2222115 ANDHRA BANK, BHAINSA BASAR P.SATYAN ROAD BHAINSA- ARAYANA - ANDHRA 504103 ADILABAD 08752- PRADESH ADILABAD BHAINSA DIST BHAINSA ANDB0000067 231108 D.NO 4-113/3/2,GOVT JUNIOR COLLEGE ROAD,NEAR BUS ANDHRA STAND,BOATH - 949452190 PRADESH ADILABAD BOATH 504305 BOATH ANDB0002091 1 MAIN ROAD,CHENNUR, ADILABAD DIST, ANDHRA CHENNUR, ANDHRA 087372412 PRADESH ADILABAD CHENNUR PRADESH-504201 CHINNOR ANDB0000098 36 9-25/1 BESIDE TANISHA GARDENS, ANDHRA DASNAPUR, PRADESH ADILABAD DASNAPUR ADILABAD - 504001 ADILABAD ANDB0001971 NO NONMICR ORIENT CEMENT WORKS CO, DEVAPUR,ADILABAD DIST, DEVAPUR, ANDHRA ANDHRA PRADESH- 08736 PRADESH ADILABAD DEVAPUR 504218 DEVAPUR ANDB0000135 240531 DOWEDPALLI, LXXETTIPET 08739- ANDHRA VILLAGE, GANDHI DOWDEPAL 233666/238 PRADESH ADILABAD DOWDEPALLI CHOWK LI ANDB0000767 222 H NO 1-171 VILL -

HYDERABAD Cushman & Wakefield Global Cities Retail Guide

HYDERABAD Cushman & Wakefield Global Cities Retail Guide Cushman & Wakefield | Hyderabad | 2019 0 Hyderabad is the capital of the newly-formed Indian state of Telangana. It is located on the banks of the Musi River, surrounding the Hussainsagar Lake in the Deccan Plateau of Southern India. The city’s area is 650 square kilometres and has a population of 9.7 million. Among the cities of Telangana, Hyderabad is the largest contributor to the state’s GDP, state tax and other revenues. Hyderabad has emerged as a hub for the information technology, pharmaceuticals and biotechnology industries and is known as “India’s pharmaceutical capital” and “Genome Valley of India”. The city is a major centre for higher education and research, and is among the global centres of information technology for which it is known as Cyberabad (Hi-Tech City). Hyderabad’s retail market is characterised by unorganised retailers such as ‘Mom and Pop’ shops and organised local retail chains such as department stores. The city’s retail market is mostly concentrated on main streets due to a lack of shopping centres. However, with new developments coming on stream and government support for FDI in retail, it is expected that there will be a surge in Hyderabad’s retail market prospects. The city government’s proactive steps, investor-friendly policies and improving infrastructure are reviving business sentiments, attracting investments and major companies, whilst boosting its real estate market activities. The retail market has seen significant momentum in recent times with retail leasing seeing an upward trend. Demand is largely driven by the apparel, entertainment and F&B sectors. -

Ankapur in Nizamabad District

Mokila is suburban village within the vicinity of the Hyderabad about 40km in Ranga Reddy District Sarpanch Name: Shri Anand 1. Though this village is near by Hyderabad in Ranga Reddy district, no Industries around , unemployment persists as educated people are increasing 2. Ground water level is less, additional bores were dug (at 500 ft) still drinking water problem exists, some bores failed, distribution of water is impacted by lack of power. One RO plant is donated by donor covers 25% village 3. No Junior College in the village or Mandal itself, students go to HYD/near by towns, Health Center and Community hall also required 4. No kuntas or cheruvus, No Library in the village, library failed earlier due to lack of maintenance, belt shops resurfaced, 320 pensions 5. Though village is close to HYD, no bus facility in the morning, recently one night halt bus is allotted. 6. Paddy, Vegetables, Mirchi, ground nut are harvested, taken to Rytu bazar, and local markets, not much cattle in the village 7. 60% of land is in Real estate , land cost for 1 acre is 1 Cr next to road, inside 50/60 lakhs, though some villagers sold lands they still doing labor. 8. Labor go to near by college or RE ventures for living, 25/30 percent drink toddy, 30% other drinks, 9. School has necessary infrastructure including computers, dining hall construction and toilet maintenance is done by Panchayat, teachers are motivated. 10. Group of village sarpanches in the mandal, are visiting hostels, hospital, resulted in better maintenance of hostel/hospital, Need to increase the Mid day meal quantity, providing fine rice now, but sanna (fine) rice did not increase attendance 11. -

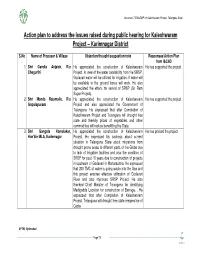

Action Plan to Address the Issues Raised During Public Hearing for Kaleshwaram Project – Karimnagar District

Annexure 7 EIA&EMP for Kaleshwaram Project, Telangana State Action plan to address the issues raised during public hearing for Kaleshwaram Project – Karimnagar District S.No Name of Proposer & Village Objection/thought/suggestion/note Responses/Action Plan . from I&CAD 1. Shri Gandla Anjaiah, R/o He appreciated the construction of Kaleshwaram He has supported the project. Chegurthi Project. In view of the water availability from the SRSP, Godavari water will be utilized for irrigation. If water will be available in the ground bores will work. He also appreciated the efforts for revival of SRSP (Sri Ram Sagar Project). 2. Shri Manda Rajamallu, R/o He appreciated the construction of Kaleshwaram He has supported the project. Gopalapuram Project and also appreciated the Government of Telangana. He expressed that after Completion of Kaleshwaram Project and Telangana will drought free state and thereby prices of vegetables and other commodities will reduce benefitting the State. 3. Shri Gangula Kamalakar, He appreciated the construction of Kaleshwaram He has praised the project. Hon'ble MLA, Karimnagar Project. He expressed his sadness about current situation in Telangana State about migrations from drought prone areas to different parts of the Globe due to lack of Irrigation facilities and also the condition of SRSP for past 10 years due to construction of projects in upstream of Godavari in Maharashtra. He expressed that 200 TMC of water is going waste into the Sea and this project ensures effective utilization of Godavari River and also improves SRSP Project. He also thanked Chief Minister of Telangana for identifying Medigadda Location for construction of Barrage. -

Telangana Abstract

GOVERNMENT OF TELANGANA ABSTRACT Agriculture and Cooperation Department – Pradhan Manthri Fasal Bhima Yojana (PMFBY) for Implementation of “Village as Insurance Unit ” and “Mandal as Insurance Unit Scheme under PMFBY in the State during Kharif 2019 and Rabi 2019-20 season-Notification - Orders – Issued. AGRICULTURE & CO-OPERATION (Agri.II.) DEPARTMENT G.O.Rt.No. 156 Dated: 03-05-2019 Read the following: 1. From the Joint Secretary to Govt. of India, Ministry of Agriculture, DAC, New Delhi Lr.No. 13015/03/2016-Credit-II, Dated.23.02.2016. 2. Commissioner of Agriculture, Hyderabad Lr. No. Crop Ins.(2)/ 60/ 2019 Dated 22-04-2019. -oOo- O R D E R: The following Notification shall be published in the Telangana State Gazette: N O T I F I C A T I O N The Government of Telangana hereby notify the Crops and Areas (District wise) during Kharif 2019 and Rabi 2019-20 to implement the “Village as Insurance Unit ” for one major crop of the District and other crops are covered under Mandal Insurance Unit scheme during Kharif 2019 and Rabi 2019-20 season under Pradhan Mantri Fasal Bhima Yojana (PMFBY) in (32) Districts of the State. The main features/Operational modalities of the Scheme vide Annexures I to IX Statements 1-32 and Proforma A&B are Appended to this order. The details of the District wise Crops covered under Village as Insurance Unit under PMFBY scheme selected for notification are as follows: S. District Crop to be S. District Crop to be No notified No notified (VIS) (VIS) 1. -

Nizamabad District

CENSUS 1961 ANDHRA PRADESH DIS T 'R leT C E'N SUS HAN D BOO K ' NIZAMABAD DISTRICT A. CHANDRA SEKHAR OF THE INDIAN ADMiNISTRATIVE SERVICE Superintendent of Census Operations, Andhra Pradesh PUBLISHED BY THE GOVERNMENT OF ANDHRA PRADESH 1965 Price: Rs. 8.00 p or 18 Sh. 8 d or $ 2.88 c. /1961 CENSUS PUBLICATIONS, ANDHRA PRADESH CENTRAL PUBLICATIONS STATE REPORTS & TABLES PART I . rGeneral Report (with Sub-parts) . .. -: Report on Vital Statistics lSubsidiary Tables PART II-A General Pepulation Tables PART II-B(i) Economic Tables (B-1 to B-IV) PART II-B(ii) Economic Tables (B-¥ to B-IX) PART II-C Cultural and Migration Tables PART III Household Economic Tables PART IV-A Report on Honsingand EstabUshments (with Subsidiary Tables) PART IV-B Housing and Establishment Tables PART V-A Special Tables for Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes PART V-B Ethnographic Notes on. Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes PART VI Village Survey Monographs PART VII-A (i)-: Handicraft Survey Reports (Selected Crafts) PART VU-A (ii)f PART VII-B Fairs and Festivals PART VIII-A Administration Report - Enumeration 'I j- ( Not for sale) PART VIII-B Administration;Report- Tabulation PART IX State Atlas PART X Special Report on Hyderabad City STATE PUBLICATIONS DISTRICT CENSUS HAND BOOKS A District Census Hand Book for each of the 20 Districts in Andhra Pradesh fRINTEP BY TIlE JYOTHI PRESS, HYDERABAD FOR THE DIRECTOR OF l'RINTlNG, HYDERABAD • PREFACE The District Census Handbook is an innovation introduced at the 1951 Census. The Handbooks are compiled by the Census Office but published by the State Government. -

(Under Right to Information Act, 2005) Samachara Hakku Bhavan, D.No.5

TELANGANA STATE INFORMATION COMMISSION (Under Right to Information Act, 2005) Samachara Hakku Bhavan, D.No.5-4-399, ‘4’ Storied Commercial Complex, Housing Board Building, Mojam Jahi Market, Hyderabad – 500 001. Phone Nos: 040-24743399 (O); 040-24740592(F) Appeal No:16895/SIC-BM/2018, Order dated:13-08-2019 Appellant : Sri Chenna Narsimlu, H.No.8-82/9, Ankapur Village, Armoor Mandal, Nizamabad District- 503224. Respondents : The Public Information Officer (U/RTI Act,2005) / The Deputy Tahsildar, Armoor Mandal, Armoor, Nizamabad District-503224. The First Appellate Authority (U/RTI Act, : 2005) / The Revenue Divisional Officer, Armoor Division, Nizamabad District-503224. ORDER Sri Ch. Narsimlu has filed 2nd appeal dated 28-12-2018 which was received by this Commission on 31-12-2018 for not getting the information sought by him from the Public Information Officer / Deputy Tahsildar, Armoor Mandal, Nizamabad District and the 1st Appellate Authority/ Revenue Divisional Officer, Armoor Division, Nizamabad District. The brief facts of the case as per the appeal and other records received along with it are that the appellant herein filed an application dated 14-09-2018 before the Public Information Officer requesting to furnish the information under Sec. 6(1) of the RTI Act, 2005 on the following points mentioned: TSIC (P.T.O) Note: This is system generated copy and no signature is required. -2- The Public Information Officer through Lr. No. C/2323/2018 dated 12-10-2018 furnished available information to the appellant. Stating that the appellant was not satisfied with the reply of the Public Information Officer, he filed 1st appeal dated 31-10-2018 before the First Appellate Authority requesting him to furnish the information sought by him u/s 19(1) of the RTI Act, 2005. -

"Assistance for Boosting Seed Production in Private Sector" (AS on 31.01.2020) Sl

DETAIL OF SUBSIDY RELEASED UNDER CENTRAL SECTOR SCHEME on "Assistance for Boosting Seed Production in Private Sector" (AS ON 31.01.2020) Sl. NAME OF BANK NAME OF BENIFICiARY STATE DISBURSEMENT CHEQUE DATE Amount (Rs.) Amount (Rs.) NO ADVICE NO. / NO disbursed disbursed Date (First Installment) (Balance /IInd Installment) FINANCIAL YEAR 2005-06 1 Punjab National Bank M/s. Om Sakthi Seeds (Firm) Tamil Nadu 1.02.2006 345701 1.02.2006 60755 22578 New Dharampuram Road, Palani, S.No. 1/53, P.S. Angammal Ginning 772725 14.11.2007 Dindigual District, Tamil Nadu Factory Compound, Dindigual, Palani Main Road 2 Bank of Baroda Sh. K. Tharaneetharam, MSc.(Agril), Tamil Nadu 1.02.2006 345702 1.02.2006 52520 45019 C-66, Gandhi Nagar, Udumalpet M/s. Dharani Agro Amuthalayam Siva 772713 3.10.2007 Branch, Udumalpet-642 154 Sakthi Colony, Dharampuram Road, Coimbatore Distt. Tamil Nadu Udumalpet 3 Union Bank of India M/s. N.M. Trading Company, Gujarat 22.02.2006 345703 22.02.2006 125000 13889 Relief Road Branch, N.L. Trust 23, Shanti Sadan Estate, Opp. Dinbai 772787 18.06.2008 Bldg. P.B. No. 303, Relief Road, Tower, Mirzapur Road, Ahmedabad-380 Ahmedabad-380 001 001 (Gujarat) FINANCIAL YEAR 2006-07 4 Corporation Bank M/s. Malleswara Agro Services Main Karnataka 18.04.2006 345704 18.04.2006 327215 228340 D.No. I, II Ward Main Road Moka, Road, Opp. KPCTL Sub Station, New 772716 23.10.2007 583, 117 Tq. Bellary, Distt. Bellary Moka Post (Bellary Tq. & Distt.) 5 Central Bank of India M/s.