2015 Mammal Damage Management in Maryland and DC EA

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Report for the Northern Virginia Well Amphipod (Stygobromus Phreaticus) August 2019 Version 1.1

Species Status Assessment (SSA) Report for the Northern Virginia Well Amphipod (Stygobromus phreaticus) August 2019 Version 1.1 Stygobromus phreaticus. Photo provided by: Michelle Brown, National Museum of Natural History, Smithsonian Institution U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Northeast Region ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The research for this document was prepared by Jacob Osborne (U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS)—North Attleboro Fish Hatchery) with technical assistance from Krishna Gifford (USFWS—Northeast Regional Office). We greatly appreciate the assistance of the following individuals who provided helpful information and/or review of the draft document: • Chris Hobson and William Orndorff (Virginia Department of Conservation and Recreation, Natural Heritage Program) • Dorothy Keough, John Pilcicki, Christopher Manikas, and Lindsey David (U.S. Army Garrison Fort Belvoir) • Robert Denton (Geoconcepts Engineering, Inc.) • Cindy Schulz , Sumalee Hoskin, Susan Lingenfelser, and Serena Ciparis (USFWS— Virginia Ecological Services Field Office (VAFO) • Anthony Tur and Jean Brennan (USFWS—Northeast Regional Office) • Meagan Kelhart (formerly, USFWS—Headquarters) We also thank our peer reviewers: • Steve Taylor (Colorado College) • Dave Culver (American University, retired) • Dan Fong (American University) • Olivia DeLee (U.S. Geological Survey, Northeast Climate Adaptation Science Center) Suggested reference: U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 2019. Species status assessment for the Northern Virginia Well Amphipod (Stygobromus phreaticus). Version -

The Possibility of the Occurrence of Hay's and Kenk's Spring

Cover Page Title: The Possibility of the Occurrence of Hay’s and Kenk’s Spring Amphipods Near the Purple Line Metro Route and Its Implications Prepared by: David C. Culver, Ph.D. Professor of Environmental Science American University 4400 Massachusetts Ave. NW Washington, DC 20016 Major sections: I. Credentials and expertise II. Introduction to the biology of Stygobromus amphipods in the Rock Creek drainage III. Ranges and potential ranges of Hay’s and Kenk’s spring amphipods IV. Threats to Hay’s and Kenk’s spring amphipods V. Towards a recovery plan for Hay’s and Kenk’s spring amphipods VI. References Length of report: 7 pages I certify that this is solely my statement. Affiliations are used for identification purposes only. David Clair Culver _________________________________ I. Credentials and expertise A graduate of Grinnell College (B.A.) and Yale University (Ph.D.), I have devoted most of my scientific career to the study of the biology of subterranean animals, especially in caves. I have written four books and over 100 scientific articles on the subject of subterranean life. My first book, Cave Life, published in 1982 by Harvard University Press, has been cited nearly 500 times in the scientific literature. My research over the past ten years has focused on shallow subterranean habitats, such as the seeps where Hay’s and Kenk’s spring amphipods are found. This work is summarized in the forthcoming book, written with Tanja Pipan, Shallow Subterranean Habitats: Ecology, Evolution, and Conservation, to be published by Oxford University Press in June, 2014. Since 2002, under a variety of contracts and cooperative agreements, I have been working on Stygobromus amphipods in national parks of the National Capitol region, including Rock Creek Park, George Washington Memorial Parkway, and others. -

Amphipoda: Crangonyctidae)

bs_bs_banner Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society, 2013, 167, 227–242. With 8 figures Cryptic diversity within and amongst spring-associated Stygobromus amphipods (Amphipoda: Crangonyctidae) JOSHUA Z. ETHRIDGE1*, J. RANDY GIBSON2 and CHRIS C. NICE1 1Department of Biology, Texas State University, 601 University Drive, San Marcos, TX 78666, USA 2San Marcos US Fish and Wildlife Service, San Marcos, TX, USA Received 3 May 2012; revised 14 September 2012; accepted for publication 24 September 2012 Multiple species of troglomorphic, spring-associated Stygobromus amphipods, including the endangered, narrow- range endemic Stygobromus pecki, occupy sites in the Edwards Plateau region of North America. Given the prevalence of cryptic diversity observed in disparate subterranean, animal taxa, we evaluated geographical genetic variation and tested whether Stygobromus contained undetected biodiversity. Nominal Stygobromus taxa were treated as hypotheses and tested with mitochondrial sequence cytochrome oxidase C subunit 1, nuclear sequence (internal transcribed spacer region 1), and AFLP data. Stygobromus pecki population structure and diversity was characterized and compared with congeners. For several Stygobromus species, the nominal taxonomy conflicted with molecular genetic data and there was strong evidence of significant cryptic diversity. Whereas S. pecki genetic diversity was similar to that of congeners, mitochondrial data identified two significantly diverged but sympatric clades. AFLP data for S. pecki indicated relatively recent and ongoing gene flow in the nuclear genome. These data for S. pecki suggest either a substantial history of isolation followed by current sympatry and ongoing admixture, or a protracted period of extremely large effective population size. This study demonstrates that Edwards Plateau Stygobromus are a complex, genetically diverse group with substantially more diversity than currently recognized. -

Petition for a Recovery Plan for the Hay's Spring Amphipod

BEFORE THE SECRETARY OF THE INTERIOR PETITION FOR A RECOVERY PLAN FOR THE HAY’S SPRING AMPHIPOD (STYGOBROMUS HAYI) Photo Credit: David Culver and Irena Šereg 2004 Center for Biological Diversity July 28, 2014 Sally Jewell Dan Ashe Secretary Director Department of the Interior U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service 1849 C Street NW 1849 C Street NW Washington, D.C. 20240 Washington, D.C. 20240 Re: Petition to the U.S. Department of Interior and the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service for the Development of a Recovery Plan for the Hay’s spring amphipod (Stygobromus hayi). Dear Secretary Jewell and Director Ashe: Pursuant to 16 U.S.C. § 1533(f) of the Endangered Species Act and section 5 U.S.C. § 553 of the Administrative Procedure Act, the Center for Biological Diversity (“Center”) hereby petitions the U.S. Department of the Interior (“DOI”), by and through the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (“Service”), to meet its mandatory duty to develop a recovery plan for the Hay’s spring amphipod (Stygobromus hayi) to ensure its full recovery. The petition requests that the Service develop a set of recovery actions to (1) improve forest habitat, including groundwater and surface water flows, around the springs where Hay’s spring amphipod are known to occur or are likely to be present, (2) address pesticide use in areas around suitable habitat, (3) identify development activities that may harm the Amphipod, (4) address flooding risks, and (5) identify additional areas in Rock Creek Park in Washington D.C. and in Maryland where reintroductions and translocation of Hay’s spring amphipods could occur. -

Chapter 6 – Conservation Actions – Species

Chapter 6 – Conservation Actions – Species Birds of Greatest Conservation Need Bobolink Dolichonyx oryzivorus STATUS: Populations in the eastern U.S. have declined since the early 1900s. North American Breeding Bird Survey data indicate a significant population decline in North America in recent decades. Status within the District of Columbia is undetermined. RANGE: Breeds in the northern United States and southern Canada and winter in southern South America from Peru to Argentina. It is a passage migrant through the District of Columbia. LOCAL HABITAT: Kenilworth Park, Anacostia Park, Rock Creek National Park, and Fort Circle Parks area. SPECIES ECOLOGY: Bobolinks use tall grass fields, pastures, and grain fields for breeding. In some areas, they favor hayfields in close association with dairy farms. In spring and summer, their diets consists largely of insects, especially caterpillars, grasshoppers, and beetles, but in fall it also includes large quantities of weed seeds, wild rice, and bristlegrass. Nests are usually placed in a scrape, either natural or created by the female. Clutch size varies from 4 to 7 eggs. THREATS: Primary threats are due to loss of suitable habitat. Changing agricultural practices and the loss of farmland to development are key factors contributing to species decline. CONSERVATION ACTION: : Need to identify and conserve grasslands. Studies to determine precise status and habitat use within the District. SITE MAP: 4 REFERENCES: 1-4 Acadian Flycatcher Empidonax virescens STATUS: BBS data from 1966 through 1989 show stable populations in the Eastern region and in neighboring Maryland. RANGE: Breeds from southern Minnesota east through southern New England, south to Gulf Coast and central Florida. -

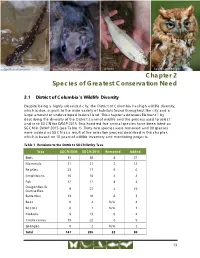

Chapter 2 Species of Greatest Conservation Need

Spotted salamander Southern flying squirrel Alewife Eastern screech owl Chapter 2 Species of Greatest Conservation Need 2.1 District of Columbia’s Wildlife Diversity Despite being a highly urbanized city, the District of Columbia has high wildlife diversity, which is due, in part, to the wide variety of habitats found throughout the city and a large amount of undeveloped federal land. This chapter addresses Element 1 by describing the diversity of the District’s animal wildlife and the process used to select and rank SGCN for SWAP 2015. Two hundred five animal species have been listed as SGCN in SWAP 2015 (see Table 1). Thirty-two species were removed and 90 species were added as SGCN as a result of the selection process described in this chapter, which is based on 10 years of wildlife inventory and monitoring projects. Table 1 Revisions to the District’s SGCN list by Taxa Taxa SGCN 2005 SGCN 2015 Removed Added Birds 35 58 4 27 Mammals 11 21 2 12 Reptiles 23 17 6 0 Amphibians 16 18 2 4 Fish 12 12 4 4 Dragonflies & 9 27 2 19 Damselflies Butterflies 13 10 6 3 Bees 0 4 N/A 4 Beetles 0 1 N/A 1 Mollusks 9 13 0 4 Crustaceans 19 22 6 9 Sponges 0 2 N/A 2 Total 147 205 32 90 13 Chapter 2 Species of Greatest Conservation Need 2.1.1 Terrestrial Wildlife Diversity The District has a substantial number of terrestrial animal species, and diverse natural communities provide an extensive variety of habitat settings for wildlife. -

Systematics of the Subterranean Amphipod Genus Stygobromus (Crangonyctidae), Part II: Species of the Eastern United States

Systematics of the Subterranean Amphipod Genus Stygobromus (Crangonyctidae), Part II: Species of the Eastern United States JOHN R. HOLSINGER SMITHSONIAN CONTRIBUTIONS TO ZOOLOGY · NUMBER 266 SERIES PUBLICATIONS OF THE SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION Emphasis upon publication as a means of "diffusing knowledge" was expressed by the first Secretary of the Smithsonian. In his formal plan for the Institution, Joseph Henry outlined a program that included the following statement: "It is proposed to publish a series of reports, giving an account of the new discoveries in science, and of the changes made from year to year in all branches of knowledge." This theme of basic research has been adhered to through the years by thousands of titles issued in series publications under the Smithsonian imprint, commencing with Smithsonian Contributions to Knowledge in 1848 and continuing with the following active series: Smithsonian Contributions to Anthropology Smithsonian Contributions to Astrophysics Smithsonian Contributions to Botany Smithsonian Contributions to the Earth Sciences Smithsonian Contributions to the Marine Sciences Smithsonian Contributions to Pa/eob/o/ogy Smithsonian Contributions to Zoology Smithsonian Studies in Air and Space Smithsonian Studies in History and Technology In these series, the Institution publishes small papers and full-scale monographs that report the research and collections of its various museums and bureaux or of professional colleagues in the world cf science and scholarship. The publications are distributed by mailing lists to libraries, universities, and similar institutions throughout the world. Papers or monographs submitted for series publication are received by the Smithsonian Institution Press, subject to its own review for format and style, only through departments of the various Smithsonian museums or bureaux, where the manuscripts are given substantive review. -

American University Thesis and Dissertation Template for PC 2016

© COPYRIGHT by William Farmer 2019 ALL RIGHTS RESERVED MACROINVERTEBRATE DIVERSITY AND FOOD WEB DYNAMICS OF SEEPAGE SPRING HABITATS IN THE WASHINGTON D.C. AREA BY William Farmer ABSTRACT Seepage springs are a commonly found freshwater habitat in the Washington D.C. area that are home to a variety of invertebrates including Stygobromus hayi, the only endangered species in Washington D.C. and the state amphipod, but little remains about the community structure of these habitats. We analyzed the community structure and general food web dynamics of 4 seepage springs, 1 spring, and 2 streams in the Washington D.C. area. We identified 11975 organisms of 50 unique taxa, 35 insect taxa and 15 non-insect taxa, with varying degrees of abundances from 63 samples over three seasons: Winter, Spring, and Summer. Using Jaccard’s index, it was seen that the community structure of the seepage spring environments in Great Falls, MD was similar to each other and similar over the three seasons, with an average coefficient of 0.41. While the sites were similar based on presence or absence they were each dominated by different organisms, most being either Lumbriculidae or Caecidotea kenki. Biodiversity indices of the study sites showed little to no patterns with regard to seasonal shifts or amphipod specificity. Using dual abundance stable isotope analysis of δ13C and δ15N the trophic positions of Lumbriculidae, C. kenki, Stygobromus tenuis, and Crangonyx shoemakeri were discerned, with estimates to the trophic positions of Tipula, Pseudolimnophila, and Platyhelminthes. It is still unclear exactly what S. tenuis was obtaining its energy from. -

Federal Register/Vol. 72, No. 175/Tuesday

51766 Federal Register / Vol. 72, No. 175 / Tuesday, September 11, 2007 / Proposed Rules * Elevation in feet (NGVD) + Elevation in feet (NAVD) # Depth in feet above Flooding source(s) Location of referenced elevation ground Communities affected Effective Modified ADDRESSES Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians Maps are available for inspection at Ginger Lynn Welch Complex, 810 Aquona Road, Cherokee, North Carolina. Send comments to Mr. Michell Hicks, Principal Chief for the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians, P.O. Box 455, Cherokee, North Carolina 28719. Graham County Maps are available for inspection at Graham County Mapping Department, 12 North Main Street, Robbinsville, North Carolina. Send comments to Mrs. Sandra Smith, Graham County Manager, 12 North Main Street, Robbinsville, North Carolina 28771. Town of Lake Santeetlah Maps are available for inspection at Lake Santeetlah Town Hall, 4 Marina Drive, Lake Santeetlah, North Carolina. Send comments to The Honorable Harding Hohenschutz, Mayor of the Town of Lake Santeetlah, 4 Marina Drive, Lake Santeetlah, North Caro- lina 28771. Town of Robbinsville Maps are available for inspection at Robbinsville Town Hall, 4 Court Street, Robbinsville, North Carolina. Send comments to The Honorable Bobby Cagle, Jr., Mayor of the Town of Robbinsville, P.O. Box 129, Robbinsville, North Carolina 28771. Moody County, South Dakota, and Incorporated Areas Big Sioux River ..................... Just upstream of County Highway 32 2500 feet up- None +1532 Unincorporated Areas of stream of First Avenue. None +1543 Moody County, City of Flandreau. * National Geodetic Vertical Datum. # Depth in feet above ground. + North American Vertical Datum. ADDRESSES City of Flandreau Maps are available for inspection at 1005 W. -

(SSA) Report for the Northern Virginia Well Amphipod (Stygobromus Phreaticus) August 2019 Version 1.1

Species Status Assessment (SSA) Report for the Northern Virginia Well Amphipod (Stygobromus phreaticus) August 2019 Version 1.1 Stygobromus phreaticus. Photo provided by: Michelle Brown, National Museum of Natural History, Smithsonian Institution U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Northeast Region ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The research for this document was prepared by Jacob Osborne (U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS)—North Attleboro Fish Hatchery) with technical assistance from Krishna Gifford (USFWS—Northeast Regional Office). We greatly appreciate the assistance of the following individuals who provided helpful information and/or review of the draft document: • Chris Hobson and William Orndorff (Virginia Department of Conservation and Recreation, Natural Heritage Program) • Dorothy Keough, John Pilcicki, Christopher Manikas, and Lindsey David (U.S. Army Garrison Fort Belvoir) • Robert Denton (Geoconcepts Engineering, Inc.) • Cindy Schulz , Sumalee Hoskin, Susan Lingenfelser, and Serena Ciparis (USFWS— Virginia Ecological Services Field Office (VAFO) • Anthony Tur and Jean Brennan (USFWS—Northeast Regional Office) • Meagan Kelhart (formerly, USFWS—Headquarters) We also thank our peer reviewers: • Steve Taylor (Colorado College) • Dave Culver (American University, retired) • Dan Fong (American University) • Olivia DeLee (U.S. Geological Survey, Northeast Climate Adaptation Science Center) Suggested reference: U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 2019. Species status assessment for the Northern Virginia Well Amphipod (Stygobromus phreaticus). Version -

2015 Rhode Island Wildlife Action Plan

Rhode Island Wildlife Action Plan Appendices 1a, 1b, 1c, 1d, 1e, 1f RI WILDLIFE ACTION PLAN: APPENDICES 1a, 1b, 1c, 1d, 1e, 1f Table of Contents Appendix 1a. Rhode Island SWAP Data Sources ........................................................................................ 1 Appendix 1b. Rhode Island Species of Greatest Conservation Need ........................................................ 30 Appendix 1c. Regional Conservation Needs-Species of Greatest Conservation Need ............................. 50 Appendix 1d. List of Rare Plants in Rhode Island ...................................................................................... 62 Appendix 1e: Summary of Rhode Island Vertebrate Additions and Deletions to 2005 SGCN List ............ 74 Appendix 1f: Summary of Rhode Island Invertebrate Additions and Deletions to 2005 SGCN List ........... 77 APPENDIX 1a: RHODE ISLAND WAP DATA SOURCES Appendix 1a. Rhode Island SWAP Data Sources This appendix lists the information sources that were researched, compiled, and reviewed in order to best determine and present the status of the full array of wildlife and its conservation in Rhode Island (Element 1). A wide diversity of literature and programs was consulted and compiled through extensive research and coordination efforts. Some of these sources are referenced in the Literature Cited section of this document, and the remaining sources are provided here as a resource for users and implementing parties of this document as well as for future revisions. Sources include published and unpublished -

District of Columbia Wildlife Action Plan

District of Columbia Wildlife Action Plan 2015 UPDATE District Department of the Environment July 2015 Acknowledgements Coordinator and Lead Author Damien Ossi, DDOE–Fisheries and Wildlife Lead Authors Dan Rauch, DDOE–Fisheries and Wildlife Lindsay Rohrbaugh, DDOE–Fisheries and Wildlife Shellie Spencer, DDOE–Fisheries and Wildlife Climate Change Vulnerability Assessments Jennifer L. Murrow, University of Maryland, Department of Environmental Science and Technology Editor Sherry Schwechten, DDOE–Natural Resources Updating the District of Columbia’s State Wildlife Action Plan required guidance, technical analysis, review, and editing from technical committees, internal groups, and sister agencies. Members of the DDOE review team were Jonathan Champion, Julia Robey Christian, Adriana Hochberg, Kate Johnson, Hamid Karimi, Bryan King, Karim Marshall, Daniel Ryan, Steve Saari, Mary Searing, and Matt Weber. Individuals from local, regional, and federal agencies; academia; and conservation organizations provided invaluable input concerning species, ecosystems, habitats, threats, conservation challenges, and solutions for the District. iii Preface The District of Columbia is a rapidly growing city, known in part for its beautiful parks and green spaces. With large sites like Rock Creek Park, Fort DuPont Park, the National Arboretum, and the Chesapeake and Ohio Canal Historical Park, and smaller places like Pope Branch, Alger, Linnean, and Hillcrest Parks, the District has the second highest amount of green space per capita of any city in the country. These spaces provide great value to the District’s residents and visitors, but they also act as homes or refuges for somewhat less apparent residents. Bald eagles nest overlooking the Anacostia River. American shad and rockfish swim thousands of miles to spawn in the Potomac River.