Shellfish Beds

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sediment Transport in the San Francisco Bay Coastal System: an Overview

Marine Geology 345 (2013) 3–17 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Marine Geology journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/margeo Sediment transport in the San Francisco Bay Coastal System: An overview Patrick L. Barnard a,⁎, David H. Schoellhamer b,c, Bruce E. Jaffe a, Lester J. McKee d a U.S. Geological Survey, Pacific Coastal and Marine Science Center, Santa Cruz, CA, USA b U.S. Geological Survey, California Water Science Center, Sacramento, CA, USA c University of California, Davis, USA d San Francisco Estuary Institute, Richmond, CA, USA article info abstract Article history: The papers in this special issue feature state-of-the-art approaches to understanding the physical processes Received 29 March 2012 related to sediment transport and geomorphology of complex coastal–estuarine systems. Here we focus on Received in revised form 9 April 2013 the San Francisco Bay Coastal System, extending from the lower San Joaquin–Sacramento Delta, through the Accepted 13 April 2013 Bay, and along the adjacent outer Pacific Coast. San Francisco Bay is an urbanized estuary that is impacted by Available online 20 April 2013 numerous anthropogenic activities common to many large estuaries, including a mining legacy, channel dredging, aggregate mining, reservoirs, freshwater diversion, watershed modifications, urban run-off, ship traffic, exotic Keywords: sediment transport species introductions, land reclamation, and wetland restoration. The Golden Gate strait is the sole inlet 9 3 estuaries connecting the Bay to the Pacific Ocean, and serves as the conduit for a tidal flow of ~8 × 10 m /day, in addition circulation to the transport of mud, sand, biogenic material, nutrients, and pollutants. -

Oyster Growers and Oyster Pirates in San Francisco Bay

04-C3737 1/20/06 9:46 AM Page 63 Oyster Growers and Oyster Pirates in San Francisco Bay MATTHEW MORSE BOOKER The author is a member of the history department at North Carolina State University, Raleigh. In the late nineteenth century San Francisco Bay hosted one of the American West’s most valuable fisheries: Not the bay’s native oysters, but Atlantic oysters, shipped across the country by rail and seeded on privately owned tidelands, created private profits and sparked public resistance. Both oyster growers and oyster pirates depended upon a rapidly changing bay ecosystem. Their struggle to possess the bay’s productivity revealed the inqualities of ownership in the American West. An unstable nature and shifting perceptions of San Francisco Bay combined to remake the bay into a place to dump waste rather than to find food. Both growers and pirates disappeared following the collapse of the oyster fishery in the early twentieth century. In 1902 twenty-two-year-old Oakland writer Jack London published his first book, an adventure story for boys. In the novel, London’s boy hero runs away from a comfortable middle-class home to test his mettle in the rough world of the San Francisco waterfront. Plucky but naïve, Joe Bronson soon finds himself sailing down San Francisco Bay in a rickety sloop called the Dazzler, piloted by hard-drinking French Pete and his tough orphan sidekick, the ’Frisco Kid. The Dazzler joins a small fleet of boats congregating in the tidal flats along the eastern shoreline of San Francisco Bay where French Pete orders Joe and the Kid to drag a triangular piece of steel, an oyster dredge, over the muddy bottom. -

Planning for Native Oyster Restoration in San Francisco Bay. Final Report to California Coastal Conservancy Agreement

Planning for Native Oyster Restoration in San Francisco Bay Final Report to California Coastal Conservancy Agreement # 05-134 Edwin Grosholza, Jim Mooreb, Chela Zabina, Sarikka Attoea and Rena Obernoltea aDepartment of Environmental Science and Policy University of California, Davis bCalifornia Department of Fish and Game Funding provided by the California Ocean Protection Council Introduction Historically, native Olympia oysters Ostreola conchaphila (=Ostrea lurida) (Turgeon et al. 1998) were an abundant and ecologically important part of the fauna in West Coast estuaries and an important fishery (Barnett 1963, Baker 1995). Unfortunately, the popularity of the fishery that began in the 1850s resulted in the complete collapse of native oyster populations along the west coast of the U.S. during the late 19th and early 20th centuries (Barnett 1963, Baker 1995). Not only was the fishery lost, but so were the key ecosystem services provided by native oysters. Studies of oysters in estuaries in the eastern U.S. have shown that native oyster reefs (Crassostrea virginica) act as a “foundation species” by creating a refuge from predators and physical stress as well as a food source resulting in increased local diversity of fishes and invertebrates (Zimmerman 1989, Lenihan 1999, Micheli and Peterson 1999, Lenihan et al. 2001). In the largely unstructured, soft-sediment habitats of West Coast estuaries, aggregations of native oysters were likely to have provided similar functions and have been shown to increase invertebrate species richness (Kimbro and Grosholz 2006). The introduction of exotic Pacific oysters (Crassostrea gigas) from Asia in the early 20th century provided a successful replacement for the native oyster fishery. -

San Francisco Bay Mercury TMDL Report Mercury TMDL and Evaluate New Card Is in Preparation by the Water and Relevant Information from Board

Total Maximum Daily Load (TMDL) Summary Waterbody – The San Francisco Bay is located on the Central Coast of California. It is a broad and shallow natural embayment. The northern part of the Bay has more flushing than the southern portion because the Sacramento and San Joaquin rivers discharge into the northern segment, while smaller, local watersheds provide freshwater to the southern part. Water Quality The northern and southern portions of the Bay are linked by the Central Bay, which provides the connection to the Pacific Ocean. Progress All segments of San Francisco Bay are included in this TMDL, including marine and estuarine waters adjacent to the Bay (Sacramento/San Joaquin River Delta within San Francisco Bay region, Suisun Bay, Report Carquinez Strait, San Pablo Bay, Richardson Bay, Central San Francisco Bay, Lower San Francisco Bay, and South San Francisco Bay including the Lower South Bay) (see map below). Three additional mercury- impaired waterbodies that are specific areas within these larger segments are also included in this TMDL (Castro Cove, Oakland Inner Harbor, and San Leandro Bay). San Francisco Bay – Mercury (Approved 2008) WATER QUALITY STATUS ○ TMDL targets achieved ○ Conditions improving ● Improvement needed ○ Data inconclusive Contacts EPA: Luisa Valiela at (415) 972-3400 or [email protected] San Francisco Bay Water Board: Carrie Austin at (510) 622-1015 or [email protected] Segments of San Francisco Bay Last Updated 6/15/2015 Progress Report: Mercury in the San Francisco Bay Water Quality Goals Mercury water quality objectives were identified to protect both people who consume Bay fish and aquatic organisms and wildlife: To protect human health: Not to exceed 0.2 mg mercury per kg (mg/kg) (average wet weight of the edible portion) in trophic level1 (TL) 3 and 4 fish. -

Restoring the Estuary

1 AA FrameworkFramework forfor CollaborativeCollaborative ActionAction onon WetlandsWetlands US FISH AND WILDLIFE SERVICE etlands in the San Francisco Bay Area are range of interests—including resource and regulato- Wamong the most important coastal wintering ry agencies, environmental organizations, business, and migratory stopover areas for millions of water- and agriculture—convened the San Francisco Bay fowl and shorebirds traveling along the Pacific Fly- Joint Venture (SFBJV) in June of 1995. In September way, which stretches from Alaska to South America. 1996, 20 parties representing this diverse wetlands These wetlands also provide economic benefits, constituency signed a working agreement that iden- offer a range of recreational opportunities, and con- tified the goals and objectives of the SFBJV, and the tribute to a higher quality of life for residents in the responsibilities of its board and working commit- densely populated San Francisco Bay Area. They are tees. The agreement also stated that the Implemen- essential aspects of the Bay region’s unique charac- tation Strategy would be developed to guide its par- ter and, along with the creeks that flow into the Bay, ties toward the long-term vision of the restored Bay help to define the vibrant and distinctive identities Estuary. The signatory partners recognized and of communities around the Bay. However, despite endorsed the goals of the North American Waterfowl their value, destruction of these precious natural Management Plan. However, they enlarged the goals assets continues. Today’s wetlands are only a rem- and objectives of the Plan to include benefits not nant, perhaps 20 percent of the vast wetlands seen only for waterfowl, but also for the other wildlife by the first European settlers. -

California Fish and Game “Conservation of Wildlife Through Education”

Spring 2015 81 CALIFORNIA FISH AND GAME “Conservation of Wildlife Through Education” Volume 101 Spring 2015 Number 2 CDFW Photo by Terry Maas Published Quarterly by the California Department of Fish and Wildlife 82 CALIFORNIA FISH AND GAME Vol. 101, No. 2 STATE OF CALIFORNIA Jerry Brown, Governor CALIFORNIA NATURAL RESOURCES AGENCY John Laird, Secretary for Natural Resources FISH AND GAME COMMISSION Jack Baylis, President Jim Kellogg, Vice President Richard B. Rogers, Member Jacque Hostler-Carmesin, Member Michael Sutton, Member Sonke Mastrup, Executive Director DEPARTMENT OF FISH AND WILDLIFE Charlton “Chuck” Bonham, Director CALIFORNIA FISH AND GAME EDITORIAL STAFF Vern Bleich ........................................................................................Editor-in-Chief Debra Hamilton ............ Office of Communication, Education and Outreach - AVU Jeff Villepique, Steve Parmenter ........................................... Inland Deserts Region Scott Osborn, Laura Patterson, Joel Trumbo ................................... Wildlife Branch Dave Lentz, Kevin Shaffer ............................................................. Fisheries Branch Peter Kalvass, Nina Kogut .................................................................Marine Region James Harrington .......................................Office of Spill Prevention and Response Cherilyn Burton ...................................................................... Native Plant Program Spring 2015 83 VOLUME 101 SPRING 2015 NUMBER 2 Published Quarterly by STATE OF -

Coastal Resilience Assessment of the San Francisco Bay and Outer Coast Watersheds

Coastal Resilience Assessment of the San Francisco Bay and Outer Coast Watersheds Suggested Citation: Crist, P.J., S. Veloz, J. Wood, R. White, M. Chesnutt, C. Scott, P. Cutter, and G. Dobson. Coastal Resilience Assessment of the San Francisco Bay and Outer Coast Watersheds. 2019. National Fish and Wildlife Foundation. IMPORTANT INFORMATION/DISCLAIMER: This report represents a Regional Coastal Resilience Assessment that can be used to identify places on the landscape for resilience-building efforts and conservation actions through understanding coastal flood threats, the exposure of populations and infrastructure have to those threats, and the presence of suitable fish and wildlife habitat. As with all remotely sensed or publicly available data, all features should be verified with a site visit, as the locations of suitable landscapes or areas containing flood hazards and community assets are approximate. The data, maps, and analysis provided should be used only as a screening-level resource to support management decisions. This report should be used strictly as a planning reference tool and not for permitting or other legal purposes. The scientific results and conclusions, as well as any views or opinions expressed herein, are those of the authors and should not be interpreted as representing the opinions or policies of the U.S. Government, or the National Fish and Wildlife Foundation’s partners. Mention of trade names or commercial products does not constitute their endorsement by the U.S. Government or the National Fish and Wildlife Foundation or its funding sources. NATIONAL OCEANIC AND ATMOSPHERIC ADMINISTRATION DISCLAIMER: The scientific results and conclusions, as well as any views or opinions expressed herein, are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect those of NOAA or the Department of Commerce. -

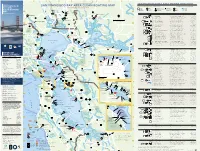

SAN FRANCISCO BAY AREA CLEAN BOATING MAP Environmental Services Call Ahead to Verify Services

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 2012-2013 SAN FRANCISCO BAY AREA MARINA DIRECTORY A A SAN FRANCISCO SAN FRANCISCO BAY AREA CLEAN BOATING MAP ENVIRONMENTAL SERVICES Call Ahead to Verify Services BAY AREA NOT INTENDED FOR NAVIGATION Oil Absorbent D Oil Absorbent Emergency Distribution and Collection Distribution Only Services Only P F C Oil Absorbent CLEAN BOATING Collection Only T Tenants Only to Sonoma to Napa to Napa MAP 29 80 John F. ALAMEDA COUNTY GRID | NAME ADDRESS PHONE Includes Marina Directory 116 12 Kennedy FAIRFIELD N Park Suisun City Marina a H4 | Aeolian Yacht Club 980 Fernside Boulevard • Alameda • 94501 (510) 523-2586 S p Schell Petaluma Marina o a 12 29 n 12 o Solano Yacht Club I9 | Alameda Marina 1815 Clement Avenue • Alameda • 94501 (510) 521-1133 C m o Creek a Shollenberger u SUISUN CITY F n B Creek B Park H4 | Ballena Isle Marina 1150 Ballena Blvd, Suite 111 • Alameda • 94501 (510) 523-5528 N Grays t C PETALUMA 116 y Cuttings Suisun City Ranch o 121 CORDELIA Boat Ramp Hudeman u Wharf H7 | Barnhill Marina 2394 Mariner Square • Alameda • 94501 (510) 521-8387 Petaluma Thir n d N t P a y O T R pa 12 E R O 0 5 Miles Cordelia G4 | Berkeley Marine Center 1 Spinnaker Way • Berkeley • 94710 (510) 843-8195 Sl Slough ou Napa Valley Marina Rush H I L g L S Gilardi’s Lakeville Marina h Suisun Ranch 0 5 Kilometers F G4 | City of Berkeley Marina 201 University Avenue • Berkeley • 94710 (510) 981-6741 Marsh Preserve River lough H9 | Embarcadero Cove Marina 1 Embarcadero Cove • Oakland • 94606 (510) 532-6683 Napa S F Napa Slough 29 G4 | Emery Cove -

Bay Farm Island: a Hidden History of Alameda by Eric J

I S S U E N U m b E r 1 • F E b r U A r Y 2 0 2 0 From the new book Bay Farm Island: A Hidden History of Alameda by Eric J. Kos and Dennis Evanosky The Ratto family gathered for this photograph on their Bay Farm Island farm about 1920. The Rattos were among the third wave of Bay Farm settlers. The first wave began in the 1850s with the arrival of Northern European farmers like Asaph Cleveland. The Portuguese followed about 20 years later and the Italians, like the Ratto family, were members of the third and final wave to arrive around the turn of the 19th to the 20th century. Image: Ratto Family. ative americans called Bay Farm Island “Wind Farm’s first settler. Benedict, Cleveland and McDonell NWhistle Island,” an isolated spot that originally held were professional farmers. Cleveland and Benedict were some 1,600 acres of marshland and 230 acres of upland. Vermont natives. Cleveland was said to bear a close Don Antonio Peralta did not include these acres in the resemblance to George Washington. sale to W.W. Chipman and Gideon Aughinbaugh. In fact Alameda County made Bay Farm Island part of Alameda the maps show Antonio’s lands do not include Bay Farm Township on October 2, 1854. This marks the first time Island. Many maps of Alameda followed suit and exclude the place name Bay Farm Island (“the place referred to the place. as the Bay Farm”) appeared in an official document. From Bay Farm’s first Northern European settlers were the start asparagus was the major cash crop. -

Regional in Nature January - February 2011 East Bay Regional Park District Activity Guide

Regional in Nature January - February 2011 East Bay Regional Park District Activity Guide www.ebparks.org “Park District Naturalists in Bay Nature Magazine” Page 3 inside. Photo: Joan Hamilton Joan Photo: Inside: Introduction to Golf • page 4 Fun for the Kids at Ardenwood • page 5 A Free Monarchs at Ardenwood • page 6 Program! See See Black Diamond in Ansel Adams’ Footsteps • page 7 Inside Make a California Indian Basket • page 8 Kids’ Programs at Crab Cove and TNA • page 9 Contents General Manager Pat O’Brien Announces Retirement Pat O’Brien, the East Bay Regional parkland development in the East Bay; Recreation .......................................4 Park District’s General Manager since • Expansion of the agency from Boating & Fishing ...........................4 1988, will retire from his post at the 66,000 acres in 1988 to over 104,000 end of 2010. acres today–an achievement that Ardenwood .................................5-6 “With regret our board has distinguishes the Park District as Black Diamond ...............................7 received notice of the impending the largest local park and recreation Botanic Garden ..............................8 retirement of our longtime General agency in the United States; Manager, Pat O’Brien,” said Doug • Dramatically increased public Coyote Hills ................................7-8 Siden, President of the Park District’s access to parklands by expanding from Crab Cove ...................................8-9 Board of Directors. “Under his 48 to 65 parks, adding over 100 miles Sunol .............................................8-9 -

Endangered Species and Essential Fish Habitat Biological Assessment

ENDANGERED SPECIES AND ESSENTIAL FISH HABITAT BIOLOGICAL ASSESSMENT Port of San Francisco Regional General Permit for Shoreline Maintenance Repair, Rehabilitation, and Replacement Activities National Marine Fisheries Service April 2015 ENDANGERED SPECIES AND ESSENTIAL FISH HABITAT BIOLOGICAL ASSESSMENT Port of San Francisco Regional General Permit for Shoreline Maintenance Repair, Rehabilitation, and Replacement Activities National Marine Fisheries Service April 2015 Prepared for: The Port of San Francisco Prepared by: Environmental Science Associates 550 Kearny Street, Suite 800 San Francisco, CA 94108 TABLE OF CONTENTS Endangered Species and Essential Fish Habitat Biological Assessment Page Glossary and Acronyms ............................................................................................................................ v Glossary ................................................................................................................................................. v Acronyms ............................................................................................................................................. vi 1. Introduction and Regulatory Authority ....................................................................................... 1‐1 1.1 U.S. Army Corps of Engineers Regulatory Authority ......................................................... 1‐4 1.2 Regulatory Requirements ........................................................................................................ 1‐4 1.3 Threatened, -

Appendix Ii Historical References for Native Stream Fishes for the Period 1854-1981, San Francisco Estuary, California

1 R.A. LEIDY APPENDIX II Historical References for Native Stream Fishes for the period 1854-1981, San Francisco Estuary, California Historical (pre-1981) distributional records for native stream fishes in Appendix 2 are organized taxonomically by family and species, and in phylogenetic order. Scien- tific nomenclature and phylogeny follow Moyle (2002). In some instances common names for species (e.g., “suckers”, “steelhead”, etc.) are used, especially when quoting di- rectly from a historical source. Within an individual species account, records are further organized by watershed and county (ies), beginning with Marsh Creek, in eastern Con- tra Costa County and continuing clockwise around the Es- tuary to Suisun Creek, Solano County. Named watersheds and tributary streams are presented in Appendix 1. Within a particular watershed, historical records are further orga- nized chronologically from earliest to most recent record. While the amount of available information varies widely between records, data is typically organized as follows: APPENDIX II HISTORICal REFERENCES FOR NATIVE STREAM FISHES FOR THE PERIOD 1854-1981 2 Collection locality (individually bolded for convenience), specimens, when available. Published sources are included date of collection or source, type of survey (e.g., visual, in the Literature Cited section of this study. electrofishing, seine or gill netting, fish kill, fish stock- ing record, etc.) and record collector(s), (source of infor- Historical records housed in museums and universities and mation and publication date, followed by page number, in agency files for Estuary streams and selected portions if applicable, and for museum collections, collection or of San Francisco Bay were collected from the sources are file number, followed by the number and size range of listed alphabetically below.