Conservation-Induced Displacement: a Comparative Study of Two Indian Protected Areas

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Club Health Assessment MBR0087

Club Health Assessment for District 317 D through February 2019 Status Membership Reports Finance LCIF Current YTD YTD YTD YTD Member Avg. length Months Yrs. Since Months Donations Member Members Members Net Net Count 12 of service Since Last President Vice Since Last for current Club Club Charter Count Added Dropped Growth Growth% Months for dropped Last Officer Rotation President Activity Account Fiscal Number Name Date Ago members MMR *** Report Reported Report *** Balance Year **** Number of times If below If net loss If no report When Number Notes the If no report on status quo 15 is greater in 3 more than of officers that in 12 within last members than 20% months one year repeat do not have months two years appears appears appears in appears in terms an active appears in in brackets in red in red red red indicated Email red Clubs less than two years old 132884 Ammathi 10/24/2017 Active 38 9 0 9 31.03% 29 0 2 M,VP,MC,SC 0 133629 Arsikere Kalpataru 01/18/2018 Active 41 1 0 1 2.50% 21 7 2 M,VP,MC,SC 5 131473 Balehonnur 06/20/2017 Active 45 10 1 9 25.00% 36 1 1 T,M,VP,MC,SC 3 133678 Ballupet 01/30/2018 Active 25 0 0 0 0.00% 20 5 2 M,VP,MC,SC N/R 133518 Bikkodu 01/03/2018 Active 27 0 3 -3 -10.00% 30 1 4 2 M,VP,MC,SC 1 132921 Channarayapatna 10/23/2017 Active 36 3 4 -1 -2.70% 20 0 6 2 P,M,VP,MC,SC 1 132955 Hariharapura 10/26/2017 Active 33 0 0 0 0.00% 38 1 P,T,M,VP,MC 0 SC 136880 Javagal 11/26/2018 Active 40 40 0 40 100.00% 0 3 T,M,VP,MC,SC N/R 90+ Days 132679 Karnire Balkunje 10/10/2017 Active 25 0 0 0 0.00% 23 1 2 M,VP,MC,SC 0 133419 -

GI Journal No. 110 1 October 29, 2018

GI Journal No. 110 1 October 29, 2018 GOVERNMENT OF INDIA GEOGRAPHICAL INDICATIONS JOURNAL NO. 111 OCTOBER 29, 2018 / KARTIKA 07, SAKA 1940 GI Journal No. 110 2 October 29, 2018 INDEX S. No. Particulars Page No. 1 Official Notices 4 2 New G.I Application Details 5 3 Public Notice 6 4 GI Applications Coorg Arabica Coffee ‐ GI Application No. 604 7 Wayanaad Robusta Coffee ‐ GI Application No. 605 Chikmagalur Arabica Coffee ‐ GI Application No. 606 Araku Valley Arabica Coffee ‐ GI Application No. 607 Bababudangiris Arabica Coffee ‐ GI Application No. 608 5 General Information 6 Registration Process GI Journal No. 110 3 October 29, 2018 OFFICIAL NOTICES Sub: Notice is given under Rule 41(1) of Geographical Indications of Goods (Registration & Protection) Rules, 2002. 1. As per the requirement of Rule 41(1) it is informed that the issue of Journal 111 of the Geographical Indications Journal dated 29th October, 2018 / Kartika 07, Saka 1940 has been made available to the public from 29th October, 2018. GI Journal No. 110 4 October 29, 2018 NEW G.I APPLICATION DETAILS App.No. Geographical Indications Class Goods 600 Leteku 31 Agricultural 601 Manipur Black Cherry 31 Agricultural 602 Manipur Black Rice (Chakhao) 30 Agricultural 603 Assam Elephant Apple 31 Agricultural 604 Coorg Arabica 30 Agricultural 605 Wayand Robusta 30 Agricultural 606 Chikmagalur Arabica 30 Agricultural 607 Araku Valley Arabica 30 Agricultural 608 Bababudangiri Arabica 30 Agricultural 609 Assam Lemon 31 Agricultural 610 Kandhamal Haldi 30 Agricultural 611 Jeeraphool 30 Agricultural -

Chikkamagalur March 2016 21 - History

MARCH 2016 U RD3052 ASSISTANT EXAMINER HH002 SUHANA SULTANA LECTURER STJ PU COLLEGE FOR WOMEN CHIKMAGALUR 577101 MARCH 2016 08 - URDU 15/04/2016 AN527 S CADAMBI PU COLLEGE CA-2 10TH MN RD BASAVESWARNGR BANGALORE 560079 13-04-2016 MARCH 2016 S OC1681 ASSISTANT EXAMINER HH004 THIRTHALINGAPPA P LECTURER GOVT PU COLLEGE PANCHANAHALLI KADUR TQ CHIKMAGLUR DT 573132 MARCH 2016 28 - SOCIOLOGY 15/04/2016 NN225 VIJAYAVITTALA PU COLLEGE KUVEMPUNAGAR MYSORE 13-04-2016 MARCH 2016 S OC1924 ASSISTANT EXAMINER HH005 A R AIRANI LECTURER GOVT SETRASIDDAPPA PU COL AJJAMPUR TARIKERE TQ CHIKMAGLUR DT 577547 MARCH 2016 28 - SOCIOLOGY 15/04/2016 NN225 VIJAYAVITTALA PU COLLEGE KUVEMPUNAGAR MYSORE 13-04-2016 MARCH 2016 P OL2097 ASSISTANT EXAMINER HH005 HANUMANTHAPPA V M LECTURER GOVT SETRASIDDAPPA PU COL AJJAMPUR TARIKERE TQ CHIKMAGLUR DT 577547 MARCH 2016 29 - POLITICAL SC 15/04/2016 TT011 DVS INDP PU COLLEGE PB NO 98 JNANADEEPIKA SHIMOGA 577201 13-04-2016 MARCH 2016 C HM1796 ASSISTANT EXAMINER HH005 SHASHIDHARA H D LECTURER GOVT SETRASIDDAPPA PU COL AJJAMPUR TARIKERE TQ CHIKMAGLUR DT 577547 MARCH 2016 34 - CHEMISTRY 15/04/2016 AS392 RNS COMP PU COLLEGE VIJAYANAGAR CHORD ROAD BANGALORE 560040 13-04-2016 MARCH 2016 S OC1686 ASSISTANT EXAMINER HH006 LOKESHAPPA C R LECTURER GOVT PU COLLEGE KADUR CHIKMAGLUR DT 577548 MARCH 2016 28 - SOCIOLOGY 15/04/2016 NN225 VIJAYAVITTALA PU COLLEGE KUVEMPUNAGAR MYSORE 13-04-2016 MARCH 2016 P OL1847 ASSISTANT EXAMINER HH006 MANJULA K S LECTURER GOVT PU COLLEGE KADUR CHIKMAGLUR DT 577548 MARCH 2016 29 - POLITICAL SC 15/04/2016 TT011 -

Bhadra Voluntary Relocation India

BHADRA VOLUNTARY RELOCATION INDIA INDIA FOREWORD During my tenure as Director Project Tiger in the Ministry of Environment and Forests, Govt. of India, I had the privilege of participating in voluntary relocation of villages from Bhadra Tiger Reserve. As nearly two decades have passed, whatever is written below is from my memory only. Mr Yatish Kumar was the Field Director of Bhadra Tiger Reserve and Mr Gopalakrishne Gowda was the Collector of Chikmagalur District of Karnataka during voluntary relocation in Bhadra Tiger Reserve. This Sanctuary was notified as a Tiger Reserve in the year 1998. After the notification as tiger reserve, it was necessary to relocate the existing villages as the entire population with their cattle were dependent on the Tiger Reserve. The area which I saw in the year 1998 was very rich in flora and fauna. Excellent bamboo forests were available but it had fire hazard too because of the presence of villagers and their cattle. Tiger population was estimated by Dr. Ullas Karanth and his love for this area was due to highly rich biodiversity. Ultimately, resulted in relocation of all the villages from within the reserve. Dr Karanth, a devoted biologist was a close friend of mine and during his visit to Delhi he proposed relocation of villages. As the Director of Project Tiger, I was looking at voluntary relocation of villages for tribals only from inside Tiger Reserve by de-notifying suitable areas of forests for relocation, but in this case the villagers were to be relocated by purchasing a revenue land which was very expensive. -

District Disaster Management Plan (DDMP)

District Disaster Management Plan (DDMP) FOR CHIKKAMAGALURU DISTRICT 2019-20 Approved by: Chairman, District Disaster Management Authority (DDMA) Cum. Deputy Commissioner Chikkamagaluru District, Karnataka Preparerd by: District Disaster Management Authority Chikkamagaluru District, Karnataka OFFICE OF THE DEPUTY COMMISSIONER Chikkamagaluru District, Karnataka Ph: 08262-230401(O); 231499 (ADC); 231222 (Fax) e.mail: [email protected]; [email protected]; [email protected] 1 P R E F A C E Chikkamagaluru district is a district with varied climatic and geographic conditions. While part of the district falls in the Malnad region, another part falls in the plain lands. Therefore the problems faced by these areas may also be different and diverse. Due to unlimited human intervention with nature and exploitation of nature, the frequency and probability of the disasters and accidents have increased drastically in the recent times. The heavy rains of August 2019 has taught the Administration to be alert and prepared for such type of disasters which are unforeseen. On the one hand heavy rains may cause floods, water logging and intense landslides, there may also be situations of drought and famine. In view of this the district has to be ready and gear itself up to meet any situation of emergency that may occur. The District Disaster Management Plan is the key for management of any emergency or disaster as the effects of unexpected disasters can be effectively addressed. This plan has been prepared based on the experiences of the past in the management of various disasters that have occurred in the district. This plan contains the blue print of the precautionary measures that need to be taken for the prevention of such disasters as well as the steps that have to be taken for ensuring that the human suffering and misery is reduced by appropriate and timely actions in rescuing the affected persons, shifting them to safer places and providing them with timely medical care and attention. -

Chikmagalur District Lists

Group "C" Societies having less than Rs.10 crores of working capital / turnover, Chikmagalur District lists. Mobile Sl No Society Name Email ID District Taluk Society Address Number 1 AIT ENGINEERING COLLEGE CO- - - Chikmagalur CHIKMAGALUR AIT ANGINEERINT COLLEGE CO-OPSO CHIKAMAGALUR ,Pin : OP-SO 577101 2 AJJANAKATTE M P C S - - Chikmagalur CHIKMAGALUR AJJANAKATTE M P C S CHIKAMAGALUR ,Pin : 577101 3 ALDHURU P A C S 8262250020 - Chikmagalur CHIKMAGALUR ALDHURU PA C S CHIKMAGALUR DIST ,Pin : 577101 4 AMAANATH VI.CO-OP-SO - - Chikmagalur CHIKMAGALUR AMAANATH VI CO-OP SO CKM ,Pin : 577101 5 AMBALE P A C S 8262269238 - Chikmagalur CHIKMAGALUR AMBALE PA C S AMBALE CHIKAGALUR ,Pin : 577101 6 ANNURU P A C S 8262260027 - Chikmagalur CHIKMAGALUR ANNURU PA CS CHIKAMAGALUR DIST ,Pin : 577101 7 ATHIGUNDI P A C S 8262231027 - Chikmagalur CHIKMAGALUR ATHIGUNDI PA C S CHIKAMAGALUR DIST ,Pin : 577101 8 AVUTHI P A C S 8262249005 - Chikmagalur CHIKMAGALUR AVUTHI PA C S CHIKAMAGALUR ,Pin : 577101 9 BELAVADI M P C S - - Chikmagalur CHIKMAGALUR BELAVADI M P C S CHIKAMAGALUR ,Pin : 577101 10 BHANDAVYA CO-OP-SO - - Chikmagalur CHIKMAGALUR BHANDAVYA COOPSO CKM ,Pin : 577101 11 BILEKALAHALLI CONSUMERS CO- - - Chikmagalur CHIKMAGALUR BILEKALAHALLI CONSUMERS CO-OPSO CKM ,Pin : 577101 OP-SO 12 BILLEKALAHALLI M P C S - - Chikmagalur CHIKMAGALUR BILEKALLAHALLI M P C S CKM ,Pin : 577101 13 BKTHARAHALLI - - Chikmagalur CHIKMAGALUR BHATHARAHALLI M P C S CKM ,Pin : 577101 14 BYIGURU P A C S 8262250120 - Chikmagalur CHIKMAGALUR BYGURU PA C S CKM ,Pin : 577101 15 CHIK-TALUK -

Chikkamagaluru

K.S.R.T.C. CHIKKAMAGALURU DIVISION: CHIKKAMAGALURU KADUR BUS STAND TEL NO-7022030216 SL NO FROM TO TYPE OF SERVICE VIA PLACES DEP TIME 1 BENGALURU ANEKAL EXPRESS ARASIKERE 12.30 2 SHIVAMOGGA ARASIKERE EXPRESS MATTIGHATTA 8.00 3 SHIVAMOGGA ARASIKERE EXPRESS MATTIGHATTA 13.00 4 SINDHANUR ARASIKERE EXPRESS MATTIGHATTA 16.30 5 GAJENDRAGAD ARASIKERE EXPRESS MATTIGHATTA 18.00 6 DHARMASTALA BALLARI EXPRESS BIRUR, TARIKERE,SHIVAMOGGA, HARIHAR 5.15 7 KADUR BALLARI EXPRESS BIRUR, TARIKERE,SHIVAMOGGA, HARIHAR 8.15 8 KADUR BALLARI EXPRESS BIRUR, TARIKERE,SHIVAMOGGA, HARIHAR 9.00 9 DHARMASTALA BALLARI EXPRESS BIRUR, TARIKERE,SHIVAMOGGA, HARIHAR 10.30 10 CHIKKAMAGALURU BALLARI EXPRESS BIRUR, TARIKERE,SHIVAMOGGA, HARIHAR 15.00 11 DHARMASTALA BALLARI EXPRESS BIRUR, TARIKERE,SHIVAMOGGA, HARIHAR 20.00 12 CHIKKAMAGALURU BELAGAVI EXPRESS BIRUR, TARIKERE,SHIVAMOGGA, HARIHAR 7.00 13 CHIKKAMAGALURU BELAGAVI EXPRESS BIRUR, TARIKERE,SHIVAMOGGA, HARIHAR 9.45 14 MYSURU BELAGAVI EXPRESS BIRUR, TARIKERE,SHIVAMOGGA, HARIHAR 10.30 15 MUDIGERE BELAGAVI EXPRESS BIRUR, TARIKERE,SHIVAMOGGA, HARIHAR 19.00 16 HASSAN BELAGAVI EXPRESS BIRUR, TARIKERE,SHIVAMOGGA, HARIHAR 21.15 17 BELAGAVI BELUR EXPRESS SAKHARAYPATNA, CHIKKAMAGALURU 17.30 18 HUBBALLI BELUR EXPRESS ARASIKERE 18.00 19 SHIVAMOGGA BENGALURU EXPRESS ARASIKERE, TUMAKURU 4.30 20 KADUR BENGALURU EXPRESS ARASIKERE, TUMAKURU 5.00 21 SHIVAMOGGA BENGALURU EXPRESS ARASIKERE, TUMAKURU 6.00 22 SHIVAMOGGA BENGALURU EXPRESS ARASIKERE, TUMAKURU 6.00 23 SHIVAMOGGA BENGALURU EXPRESS ARASIKERE, TUMAKURU 6.30 24 SHIVAMOGGA BENGALURU -

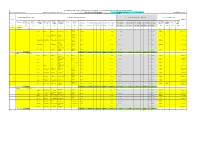

Statement Showing the Details of Minority Coloney Development

STATEMENT SHOWING THE DETAILS OF MINORITY COLONEY DEVELOPMENT SCHEME WORKS Head of Account / Chargeble to 4225-03-277-2-10 {Object Code (386)} Name of District: Chickmagalur Progress Report Upto End of 30-11-2018 Amount Rs. In Lakhs Note: Before Filling the details, Please Refer the Worksheet - Grants Released & also refer Guidelines Amount Released By Director, DOM Programme (Works Approved By D.C) Progress Achieved (Physical & Finacial) Name of Executing Agency Sl. No. Remarks Name of Name of Name of Area Roads & Drains / Pure Drinking Borewell Community Grand Total Roads & Drains / Pure Drinking Borewell Community Grand Total Roads & Pure Commun Amount ( Date of Name of Gram Name of Borewell Constituency Constituency Town / / Extension / Sl. No. Drains / UGD Drinking ity Rs. In Lakhs) Release Panchayath Work Nos. Amount Nos. Amount Nos. Amount Nos. Amount Nos. Amount Nos. Amount Nos. Amount Nos. Amount Nos. Amount Nos. Amount Works / Taluka Village Location / Works Water Toilets (10a (11a (12a (1) (2a) (2b) (2c) (3) (4) (5) (6) (7a) (7b) (8a) (8b) (9a) (9b) (10b) (11b) (12b) (13a) (13b) (14a) (14b) (15a) (15b) (16a) (16b) (17a) (17b) (18a) (18b) (18c) (18d) (19) ) ) ) I MLA 1 Chikmagalur 50.00 23.08.17 Concrete Kadur Hulikere Hulikere Muslim Street 1 Road & 1 10.00 1 10.00 1 10.00 1 10.00 KRIDL Completed Drainage Concrete S.Bommanaha Christian Kadur Chikkadevanoor 2 Road & 1 10.00 1 10.00 1 10.00 1 10.00 KRIDL Completed lli Colony Drainage Concrete Chickmagalur Mallenahalli Mallenahalli Behind Masjid 3 Road & 1 8.00 1 8.00 1 8.00 1 -

MLA Constituency Name Sringeri

MLA Constituency Name Mon Aug 24 2015 Sringeri Elected Representative :D. N. Jeevaraja Political Affiliation :Bharatiya Janata Party Number of Government Schools in Report :321 KARNATAKA LEARNING PARTNERSHIP This report is published by Karnataka Learning Partnership to provide Elected Representatives of Assembly and Parliamentary constituencies information on the state of toilets, drinking water and libraries in Government Primary Schools. e c r s u k o o S t o r e l e B i t o a h t t t T e i e W l l i n i W g o o o y y n T T i r r m k s a a s r r l m y n r i b b i o o r i i District Block Cluster School Name Dise Code C B G L L D CHIKKAMANGALORE BIRURU BALLAVARA GLPS. THIMMAIANA BYLU 29170801301 Others CHIKKAMANGALORE CHIKMAGALUR HUYIGERE G.L.P.S. CHOTTEGADDE 29170600804 Others CHIKKAMANGALORE CHIKMAGALUR HUYIGERE GHPS HUIGERE 29170600803 Well CHIKKAMANGALORE CHIKMAGALUR HUYIGERE GHPS SH BAILU 29170600805 Others CHIKKAMANGALORE CHIKMAGALUR HUYIGERE GLPS BIKKARANE 29170600901 Well CHIKKAMANGALORE CHIKMAGALUR HUYIGERE GLPS KARAGANA 29170600801 Tap Water CHIKKAMANGALORE CHIKMAGALUR HUYIGERE GLPS KASKEMANE 29170601103 Others CHIKKAMANGALORE CHIKMAGALUR HUYIGERE GLPS MANABOOR 29170601001 Hand Pumps CHIKKAMANGALORE CHIKMAGALUR HUYIGERE GLPS KHANAGUDDA 29170600806 Well CHIKKAMANGALORE CHIKMAGALUR KADAVANTHI G.L.P.S. BILUGOLA 29170600310 Tap Water CHIKKAMANGALORE CHIKMAGALUR KADAVANTHI GHPS BIDARE 29170600204 Tap Water CHIKKAMANGALORE CHIKMAGALUR KADAVANTHI GHPS KADAVANTHI 29170600402 Tap Water CHIKKAMANGALORE CHIKMAGALUR KADAVANTHI GHPS SHIRAGOLA -

KUVEMPU UNIVERSITY DIRECTORATE of DISTANCE EDUCATION Details of the Admissions Made for the Academic Session 2018-19 (July, 2018) Under Open and Distance Learning 1

KUVEMPU UNIVERSITY DIRECTORATE OF DISTANCE EDUCATION Details of the admissions made for the academic session 2018-19 (July, 2018) under Open and Distance Learning 1. Programme-wise details a) Bachelor of ARTS Government Issued Category Identifier ( eg: Date of Sl.No. Name of the students Enrolment No. SC/ST/OBC/PW Contact Details (Ph. No. , email id etc) AADHAR Card / PAN admission D*/EWS** Card / Voter Id Card No. etc.) 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 9742675743 [email protected] D NO 209 E BLOCK AASHRAYA BADAVANE 1 AJAY N DUBA155010010 16-10-2018 OBC 345611851409 BOMMANAKATTE VINOBANAGARA SHIMOGA KARNATAKA 577204 9113634722 [email protected] AMRITHA, D/O RAMBAHADUR, SRIDAAMA, 2 AMRITHA DUBA155050527 16-10-2018 GM BHASKAR SHETTY COMPOUND, KUKKIKATTE, 79 359795230408 BADAGABETTU, UDUPI, PIN :576101 Karnataka 6361510475 [email protected] S/O DODDAPPA MATTIGHATTA GRAM SHETTIHALLI 3 ANITHA M D DUBA155010013 17-10-2018 OBC 405868384425 POST SHIVAMOGA SHIVAMOGA KARNATAKA 577227 9148007032 [email protected] ANNAPOORNA B S D/O SUBAIAH B D, #565, 4 ANNAPOORNA B S DUBA155050525 16-10-2018 SC BIDARAHALI VILLAGE, MUDIGERE TALUK, 765693110317 CHIIKMAALUR, 577132 Karnataka 9611876238 [email protected] ANU N D D/O DANEGOWDA, NETTEKERE HALLI 5 ANU N D DUBA155050549 16-10-2018 OBC CHIKMAGALURU, KURUVANGI POST, 622335164528 CHIKMAGALURU 577102 Karnataka 8722531835 [email protected] NAGENAHALLI VILLAGE AND POST KADUR TALUK 6 ANURADHA J DUBA155050006 17-10-2018 OBC 394011756249 CHIKKAMAGALURU DIST CHIKKAMAGALURU KARNATAKA 577168 1 KUVEMPU -

Ethno-Botanical Wealth of Bhadra Wild Life Sanctuary in Karnataka

Indian Journal of Traditional Knowledge Vol. 3(1), January 2004, pp. 37-50 Ethno-botanical wealth of Bhadra wild life sanctuary in Karnataka M Parinitha, G U Harish, N C Vivek, T Mahesh and M B Shivanna* Department of Studies and Research in Applied Botany, Kuvempu University Jnana Sahyadri, Shankaraghatta 577451, Shimoga District, Karnataka Received 18 February 2003; revised 17 October 2003 Ethno-botanical surveys were conducted during 1998 and 99 in villages of Bhadra Wild Life Sanctuary area, situated in the Western Ghats region of Karnataka. Results of the study indicated that 60 plant species belonging to 50 genera and 35 families were used for preparing at least 78 herbal drugs by the medicine men. Among the plant species, the utilization of leaves of Centella asiatica, roots of Ichnocarpus frutescens and decoction of leaves of Bambusa arundinacea in the treatment of jaundice, diabetes and for expulsion of placenta in human’s and animals, respectively, are note worthy. Apart from the above, a few drugs formulated by the local people are not known to literature. According to a CAMP survey, Tylophora indica and Artocarpus hirsutus are vulnerable while, Dipterocarpus indicus and Rauwolfia serpentina are endangered and Spondias pinnata is a lower risk category plant. The information collected from these ‘local specialists’ enriches the countrywide database on the availability of biodiversity resources and gives full credit to the origin of information at different levels. Keywords: Ethno-botanical survey, Bhadra Wild Life Sanctuary, Western Ghats, Karnataka. Bhadra Wild Life Sanctuary situated in very conservative in nature and have a the Malnad region of the Western Ghats, great faith in their own traditional system Karnataka, is very unique in its formation of medicine. -

Assessment of Forest Encroachment in Chikmagalur District of Western

International Journal of Remote Sensing & Geoscience (IJRSG) www.ijrsg.com ASSESSMENT OF FOREST ENCROACHMENT IN CHIKMAGALUR DISTRICT OF WESTERN GHATS USING RS AND GIS Hemanjali, A.M, Research Scholar, Department of Environmental Science, Bangalore University, Bangalore, India. Pramod Kumar, G.R, Research Scholar, Department of Environmental Science, Bangalore University, Bangalore, India Somashekar, R.K, Professor, Department of Environmental Science, Bangalore University, Bangalore, India Nagaraja, B.C, Assistant Professor, Department of Environmental Science, Bangalore University, Bangalore, India pernicious practice endangering forest resources throughout Abstract the country [3]. Totally an area of 13.5 lakhs ha is catego- rized under encroached forest in the country till date and The Western Ghats, which covers about 60 % of forest wherein the share of state of Karnataka is 96,230 ha. Many area of Karnataka, is recognized as one of the bio-diversity state government and farmers have approached the court hotspots of the world. These forests are shrinking in recent informing that the survey done by Forest Department is un- years due to anthropogenic pressures, especially encroach- scientific. ment of lands for agriculture. It has led to forest fragmenta- tion, loss of habitat and corridor for movement of wild ani- The Western Ghats, which cover about 60 % of forest area mals, etc. The present study focus on RS and GIS based as- of Karnataka, is recognized as one of the bio-diversity hots- sessment of forest encroachment scenario over a period of pots of the world. The total recorded forest area of the state three decades in Chikmagalur district of Karnataka using is 43,356.45 Km2, constituting 22.60 % of the geographical Landsat TM/MSS of 1990 and 2000, and IRS P6 of 2010.