Appropriate Follow-Up Services Critical with Short Hospital Stays

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Empire Plan SEPTEMBER 2018 REPORTING ON

The Empire Plan SEPTEMBER 2018 REPORTING ON PRENATAL CARE Every baby deserves a healthy beginning and you can take steps before your baby is even born to help ensure a great start for your infant. That’s why The Empire Plan offers mother and baby the coverage you need. When your primary coverage is The Empire Plan, the Empire Plan Future Moms Program provides you with special services. For Empire Plan enrollees and for their enrolled dependents, COBRA enrollees with their Empire Plan benefits and Young Adult Option enrollees TABLE OF CONTENTS Five Important Steps ........................................ 2 Feeding Your Baby ...........................................11 Take Action to Be Healthy; Breastfeeding and Your Early Pregnancy ................................................. 4 Empire Plan Benefits .......................................12 Prenatal Testing ................................................. 5 Choosing Your Baby’s Doctor; New Parents ......................................................13 Future Moms Program ......................................7 Extended Care: Medical Case High Risk Pregnancy Program; Management; Questions & Answers ...........14 Exercise During Pregnancy ............................ 8 Postpartum Depression .................................. 17 Your Healthy Diet During Pregnancy; Medications and Pregnancy ........................... 9 Health Care Spending Account ....................19 Skincare Products to Avoid; Resources ..........................................................20 Childbirth Education -

Childbirth Education

International Journal of Childbirth Education Open Focus The official publication of the International Childbirth Education Association VOLUME 31 NUMBER 3 JULY 2016 2016 October 13 ‐15 Core Conference October 11 & 12 Preconference workshops Renaissance Denver Stapleton Hotel 3801 Quebec Street | Denver, CO 80207 Free airport shuttle Reaching the Highest Peaks in Evidence‐Based Practice Join us for the 2016 Conference! Sessions this year will include information on: Learning Lab Skills Sessions Waterbirth Science and Safety Preconference Workshops: Somatic Trauma Resolution . Professional Childbirth Self – Care for the birth professional Educator Workshop Perinatal Mood and Anxiety Disorders . Birth Doula Workshop ICEA Member reception hosted by the President . Postpartum Doula Workshop . Early Lactation Care Workshop We are excited to feature these Internationally acclaimed childbirth activists and speakers: NEW THIS YEAR! “Tools For Success” Workshop: Part 1 Creating & Developing an Effective Curriculum Part 2 PowerPoint‐ Creativity, Productivity and Professionalism Barbara Harper RN CD CCE Jennie Joseph LM CPM Rep. Kelly Townsend Doula & member of AZ House of Representatives FREE Certificate For the first time ever Attendees who attend all Concurrent Session Speakers Include: general sessions with Jennie Nicette Jukelevics | Birdie Gunyon Meyer | Jeanne Green Joseph will receive a certificate Donna Walls | Connie Livingston | Tamela Hatcher | Lisa Wilson as a Maternal Child Health Jennifer Shryock | Colleen Weeks | Jana McCarthy -

ILLINOIS MIECHV Getting Everyone on the Bus! BENCHMARKS

ILLINOIS MIECHV Getting Everyone on the Bus! BENCHMARKS: Goals, Data, Background and Resources 1 ILLINOIS MIECHV BENCHMARKS YEARS 1-3 1. Maternal and Newborn Health (Benchmarks 1-8) 2. Child Injuries; Child Abuse, Neglect or Maltreatment; and Reduction of Emergency Department Visits (Benchmarks 9- 15) 3. Improvement in School Readiness and Achievement (Benchmarks 16-18, 20-24) 4. Domestic Violence and Crime (Benchmarks 26-28) 5. Family Economic Self- Sufficiency (Benchmarks 29-30, 32) 6. Coordination and Referrals for Other Community Resources and Supports (Benchmarks 33-37) 2 ILLINOIS MIECHV BENCHMARKS 1. Maternal and Newborn Health 1. Prenatal Visit Completion 2. Parental Use of Tobacco, Alcohol and Drugs 3. Post-Partum Use of Contraception 4. Inter-Birth Interval 5. Screening for Maternal Depression 6. Breastfeeding 7. Well-Child Visit Completion 8. Insurance Status for Mother/Child 3 Benchmark 1(1.1): Prenatal Care Completion Goal & Rationale Benchmark Measurement Periods Increase proportion of enrolled women who adhere for HRSA/MIECHV to the ACOG recommended schedule for prenatal visits. Year 1: Jan 1 2012 - Sept 30 2012 Women who do not receive prenatal care are 3 Year 2: Oct 1 2012 - Sept 30 2013 to 4 times more likely to die of complications and babies are 6 times more likely to die within Year 3: Oct 1 2013 - Sept 30 2014 the 1st year of life. Year 4: Oct 1 2014 - Sept 30 2015 Adherence is a measure that compares the actual number of prenatal visits completed prior Year 5: Oct 1 2015 - Sept 30 2016 to the birth of the child to the 10 visits that are recommended and expected by the American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Illinois Outcome Data (ACOG). -

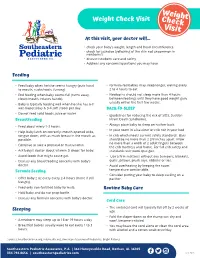

Weight Checkvisit

Weight Weight Check Visit Check Visit At this visit, your doctor will… • check your baby’s weight, length and head circumference • check for jaundice (yellowing of the skin not uncommon in newborns) • discuss newborn care and safety • Address any concerns/questions you may have Feeding • Feed baby when he/she seems hungry (puts hand • formula-fed babies may sleep longer, waking every to mouth, sucks/roots, fussing). 2 to 4 hours to eat. • End feeding when baby seems full (turns away, • Newborns should not sleep more than 4 hours closes mouth, relaxes hands). between feedings until they have good weight gain, usually within the first few weeks. • Baby is typically feeding well when he/she has 6-8 wet diapers/day & 3-4 soft stools per day. BACK-TO-SLEEP • Do not feed solid foods, juice or water. • (guidelines for reducing the risk of SIDS, Sudden Breastfeeding Infant Death Syndrome). • Always place baby to sleep on his/her back. • Feed about every 1-3 hours. • In your room in a bassinet or crib not in your bed. • Help baby latch on correctly: mouth opened wide, tongue down, with as much breast in the mouth as • In crib which meets current safety standards: Bars possible. should be no more than 2 3/8 inches apart. Allow no more than a width of 2 adult fingers between • Continue to take a prenatal or multivitamin. the crib mattress and frame. For full crib safety and • Ask baby’s doctor about vitamin D drops for baby. standards visit www.cpsc.gov. • Avoid foods that might cause gas. -

AWHONN Compendium of Postpartum Care

AWHONN Compendium of Postpartum Care THIRD EDITION AWHONN Compendium of Postpartum Care Third Edition Editors: Patricia D. Suplee, PhD, RNC-OB Jill Janke, PhD, WHNP, RN This Compendium was developed by AWHONN as an informational resource for nursing practice. The Compendium does not define a standard of care, nor is it intended to dictate an exclusive course of management. It presents general methods and techniques of practice that AWHONN believes to be currently and widely viewed as acceptable, based on current research and recognized authorities. Proper care of individual patients may depend on many individual factors to be considered in clinical practice, as well as professional judgment in the techniques described herein. Variations and innovations that are consistent with law and that demonstrably improve the quality of patient care should be encouraged. AWHONN believes the drug classifications and product selection set forth in this text are in accordance with current recommendations and practice at the time of publication. However, in view of ongoing research, changes in government regulations, and the constant flow of information relating to drug therapy and drug reactions, the reader is urged to check information available in other published sources for each drug for potential changes in indications, dosages, warnings, and precautions. This is particularly important when a recommended agent is a new product or drug or an infrequently employed drug. In addition, appropriate medication use may depend on unique factors such as individuals’ health status, other medication use, and other factors that the professional must consider in clinical practice. The information presented here is not designed to define standards of practice for employment, licensure, discipline, legal, or other purposes. -

HFNYPPM Pg.1

Healthy Families New York Site-Specific Policy and Procedures Manual March 2021 HFNYPPM pg.1 TABLE OF CONTENTS HFNY: Introduction and Mission 4 Program Goals 5 Guide to the HFNY PPM 6 Critical Element #1 Policy: Screening and Assessment Process HFA Best Practice Standard 1-2.A Policy: First Home Visit HFA Best Practice Standard 1-3.A Critical Element #2 Policy: Eligibility Requirements HFA Best Practice Standard 2-1.A Policy: Assessment Narratives HFA Best Practice Standard 2-2.A Critical Element #3 Policy: Voluntary Nature of Services HFA Best Practice Standard 3-1.A Policy: Building Trust and Engaging Families HFA Best Practice Standard 3-2.A Policy: Creative Outreach HFA Best Practice Standard 3-3.A Critical Element #4 Policy: Minimum Length of Time to Offer Weekly Home Visits HFA Best Practice Standard 4-1.A Policy: Levels of Service HFA Best Practice Standard 4-2.A Policy: Home Visit Completion HFA Best Practice Standard 4-2.B Policy: Duration of Service HFA Best Practice Standard 4-3.B Policy: Services Closure/Transition Planning HFA Best Practice Standard 4-4.A Critical Element #5 Policy: Providing Culturally Respectful Services HFA Best Practice Standard 5 Critical Element #6 Policy: Reviewing and Addressing Risk Factors and Challenging Issues HFA Best Practice Standard 6-1.A HFNYPPM pg.2 Policy: Family Goal Plan HFA Best Practice Standard 6-2.A Policy: CHEERS: Assessing Parent-Child Interaction HFA Best Practice Standard 6-3.A Policy: Promoting Child Development, Parenting Skills, Health and Safety HFA Best Practice Standard -

The Side Effects of Phototherapy for Neonatal Jaundice: What Do We Know? What Should We Do?

Eur J Pediatr (2011) 170:1247–1255 DOI 10.1007/s00431-011-1454-1 REVIEW The side effects of phototherapy for neonatal jaundice: what do we know? What should we do? Tao Xiong & Yi Qu & Stephanie Cambier & Dezhi Mu Received: 13 January 2011 /Accepted: 14 March 2011 /Published online: 1 April 2011 # Springer-Verlag 2011 Abstract Neonatal phototherapy (NNPT), a noninvasive, Introduction easily available therapy, has been widely used for the treatment of neonatal jaundice for more than half a century. Neonatal jaundice, the yellow coloration of the sclera and skin Its efficiency in decreasing plasma bilirubin concentration is caused by hyperbilirubinemia, is one of the most common well documented, and NNPT leads to greatly reduced conditions confronting neonatologists daily. About 60% of exchange transfusion rates for neonates with hyperbilirubine- term and 80% of preterm infants develop jaundice in the first mia. It is generally accepted that the side effects of NNPT are week of life [74]. Bilirubin encephalopathy is a devastating not serious and seem to be well controlled. This review will brain injury, which can cause permanent neurodevelopmental focus on these possible side effects as well as the approaches handicaps [62]. Fortunately, a noninvasive and easily to minimize them. available treatment, neonatal phototherapy (NNPT), is effective in degrading unconjugated bilirubin. Following Keywords Jaundice . Newborn infant . Phototherapy . Side the discovery of NNPT in the 1950s, many clinical trials effect have addressed its application to neonatal jaundice [42]. In 1985, the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development reported that NNPT was as effective as exchange transfusion in preventing neurological sequelae [26]. -

Infant Assessment and Reduction of Sudden Unexpected Postnatal Collapse Risk During Skin ToSkin Contact Susan M

6/11/2015 www.medscape.com/viewarticle/822017_print www.medscape.com Infant Assessment and Reduction of Sudden Unexpected Postnatal Collapse Risk During Skin toSkin Contact Susan M. LudingtonHoe, PhD, RN, CNM, CKC, FAAN; Kathy Morgan, BSN, RN, CKC, NNP BC NAINR. 2014;14(1):2833. Abstract and Introduction Abstract To encourage use of skintoskin contact with all healthy term infants during the first two hours of life and throughout their mothers' postpartum hospitalization, an easy, rapid newborn assessment tool, the "RAPP", has been developed to enhance labor and delivery and motherbaby nurses' ability to swiftly and accurately assess newborn physiologic condition. The "RAPP" assessment (respiratory activity, perfusion, and position) tool is being proposed as a way to swiftly evaluate infants' physiologic condition and position. Position of the infant is a key factor in minimizing risk of Sudden Unexpected Postnatal Collapse (SUPC). SUPC is an emerging complication of skintoskin contact and breastfeeding in the first hours and days postbirth. The "RAPP" assessment parameters and flow sheet are discussed, risk factors for SUPC are enumerated, and a checklist to prevent SUPC is presented so skintoskin contact can be safely provided. Introduction Skintoskin contact, also known as Kangaroo Care, has been recommended for all healthy term newborns by the American Academy of Pediatrics,[1] the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists,[2] the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention,[3] and the Academy of Breastfeeding -

Sudden Unexplained Early Neonatal Death Or Collapse: a National Surveillance Study

nature publishing group Population Study Articles Sudden unexplained early neonatal death or collapse: a national surveillance study Tracey L. Lutz1,2, Elizabeth J. Elliott3,4 and Heather E. Jeffery1,2 BACKGROUND: The incidence of sudden unexpected early Svenningsen (2) with a case series of 13 babies who died or had neonatal death (SUEND) or acute life-threatening events an acute life-threatening event (ALTE) on the maternity ward. (ALTEs) is reported as 0.05/1,000 to 0.38/1,000 live births. There In the United States, Burchfield and Rawlings (3) described sud- is currently no national system in Australia for reporting and den death in apparently healthy newborns in a maternity hos- investigating such cases. pital in 1991. In 2011, a report from the American Academy of METHODS: A 3-y prospective, national surveillance study, run Pediatrics emphasized that there was insufficient evidence to rec- in collaboration with the Australian Pediatric Surveillance Unit ommend bed sharing in the hospital or at home (4). Following (APSU). Data were provided by pediatricians reporting to APSU; this statement, Thach highlighted neonatal deaths that occurred and independently ascertained by the Coroner in two states while bed sharing in maternity units (5). Recent data from (NSW and QLD) and the Newborn Early Transport Network in Germany, Sweden, and England estimate an incidence of early NSW. A detailed deidentified questionnaire was created. unexpected neonatal death of between 0.05 and 0.38/1,000 live RESULTS: In NSW and QLD, the incidence was 0.1 and births (6–8). Two of the largest, prospective studies employed 0.08/1,000 live births, respectively. -

Where Do Prenatal and Postnatal Healthcare Providers Fit In?

Infant Safe Sleep in Ohio: Where Do Prenatal and Postnatal Healthcare Providers Fit In? Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Nichole Laureen Hodges, M.P.H. Graduate Program in Public Health The Ohio State University 2016 Dissertation Committee: Mira Katz, Advisor Sarah Anderson Lara McKenzie Mary Ellen Wewers Copyright by Nichole Laureen Hodges 2016 Abstract Introduction: Sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS) and sleep-related sudden unexpected infant death (SUID) are among the leading causes of infant mortality in the United States (U.S.) and are associated with significant health disparity. Healthcare professionals can influence their patients’ infant safe sleep choices; however, little is known about the practices of prenatal and postnatal healthcare providers related to this topic. The purpose of this study was to assess the infant safe sleep knowledge, attitudes, and behaviors of lactation consultants, obstetric physicians, and certified nurse midwives (CNMs) in Ohio and identify barriers and enabling/reinforcing factors associated with providing infant safe sleep education in the obstetric environment. Methods: A mixed-methods approach was used. Focus groups were held with certified lactation consultants in Ohio to discuss their role and the advice they provide to women about infant safe sleep and reducing the risk of SIDS and other causes of infant sleep- related death. Cross-sectional surveys were conducted with physicians and CNMs. Surveys were sent to a census of all licensed physicians in the registry of the State Medical Board of Ohio with “obstetrics,” “obstetrics and gynecology,” or “maternal and fetal medicine” as their first area of specialty (n=1,771) as well as all nurses included in the licensing registry of the Ohio Board of Nursing as a CNM (n=333). -

Babytalk Free Download

BABYTALK FREE DOWNLOAD Sally Ward | 352 pages | 15 Jan 2004 | Cornerstone | 9780099297208 | English | London, United Kingdom Baby TALK is represented across the nation A Detailed Birth Plan. BabyTalk third trimester of pregnancy comes with a lot of anticipation BabyTalk welcoming the The development of communication. Shore and others believe that CDS contributes to mental development as it helps teach the child the basic function and structure of language. Meredith Corporation. We can share ideas, inspirations, concerns, and successes! An Associated Press [7] article on public reaction to the image sparked hundreds of newspaper articles and TV segments highlighting the challenges that women face when attempting to BabyTalk with more than 8, letters applauding the BabyTalk to feature a nursing mom on the cover of a national magazine. CDS has been observed in languages other than English. Sat 10 Oct BabyTalk, pm. BabyTalk ultimate goal is to empower women through knowledge, within a BabyTalk environment. Need even more definitions? Can you spell these 10 commonly misspelled words? There are diminutives such as "walkie" for walk and "bathie" for bath. In these instances, the outward style of the language may be that of baby talk, but is not considered actual "parentese", as it serves a different linguistic function see pragmatics. Baby talk is a type of speech associated with an older person speaking to a child. Third Trimester. Baby food Birth weight Breast pump Breastfeeding Breastfeeding and medications Bottle feeding Colic Immunizations Cradle cap Cross eyed Failure to thrive Immunization Infant and toddler safety Infant bathing Infant food safety Infant formula Infant massage BabyTalk food safety Infant nutrition Infant respiratory distress syndrome Infant sleep training BabyTalk intensive BabyTalk unit Newborn care and safety Oral rehydration therapy Pedialyte Preterm birth BabyTalk baby syndrome Soy formula Sudden infant death syndrome Breastfeeding and mental health. -

Maternity Passport & Procedure Guide

Maternity Passport & Procedure Guide | Maternity Passport & Procedure Guide Your Hospital Stay Your Mission Rooted in the loving ministry of Jesus as healer, we commit ourselves to serving all persons with special attention to those who are poor and vulnerable. Our Catholic health ministry is dedicated to spiritually-centered, holistic care which sustains and improves the health of individuals and communities. We are advocates for a compassionate and just society through our actions and our words. Values Service of the poor: Generosity of spirit, especially for persons most in need Reverence: Respect and compassion for the dignity and diversity of life Integrity: Inspiring trust through personal leadership Wisdom: Integrating excellence and stewardship Creativity: Courageous innovation Dedication: Affirming the hope and joy of our ministry Maternity Passport & Procedure Guide | Congratulations on your pregnancy. The Ascension care team welcomes you. We are pleased that you have chosen an Ascension provider for Cesarean Delivery Rooms (C-Section) — If a cesarean delivery the birth of your baby. The experienced staff at each location is is required, a state-of-the-art operating room is conveniently committed to helping you achieve a safe and memorable birth located in the Labor and Delivery Unit. experience. We offer attentive and personal nursing care, ongoing patient education, and a family-centered approach. Ascension Mother/Baby Rooms — Each private mother/baby room is maternity services are available at these locations: designed to create a nurturing family-centered environment. • Ascension Seton Medical Center Austin • Ascension Seton Williamson Neonatal Intensive Care Units (NICUs) Ascension Seton Northwest • NICU staff embrace the family-centered approach to care.