Frederic Ozanam: His Piety and Devotion

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CARD. ANTONIO POMA- Villanterese

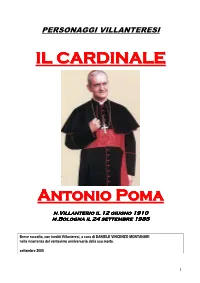

PERSONAGGI VILLANTERESI IIIIIILL CCAARRDDIIIIIINNAALLEE AAnnttoonniiiiiioo PPoommaa n.Villanterio il 12 giugno 1910 m.Bologna il 24 settembre 1985 Breve raccolta, con inediti Villanteresi, a cura di DANIELE VINCENZO MONTANARI nella ricorrenza del ventesimo anniversario della sua morte. settembre 2005 1 IL CARD. ANTONIO POMA- Villanterese Nato a Villanterio il 12.6.1910- morto a Bologna il 24 settembre 1985 Pur tra gli innumerevoli impegni del suo ministero, il Cardinale Antonio Poma ha sempre mantenuto un legame molto stretto con il paese d’origine. Numerose le sue visite a Villanterio, sia da Vescovo di Mantova che da Cardinale Arcivescovo di Bologna, per celebrare ricorrenze, cresime e suffragare i suoi genitori che riposano nel nostro cimitero. I più anziani lo chiamavano sempre affettuosamente “don Antonio” così come fece un suo compagno di classe che in questo modo lo chiamò in San Pietro quando, appena davanti a Papa Paolo VI, attraversava la navata centrale della basilica e si accingeva a ricevere la berretta cardinalizia. Chi ha avuto la fortuna di conoscerlo personalmente, ha potuto constatarne la semplicità con cui gli si poteva parlare ed il suo interessamento per ogni cosa, anche piccola, che riguardasse il paese che gli ha dato i natali. Con una solenne concelebrazione, venne festeggiato a Villanterio nel venticinquesimo della sua ordinazione episcopale e l’abbiamo visto commosso davanti all’altare dedicato alla Madonna del Carmine, allo scoprimento di una lapide commemorativa che ricordava come a quell’altare si formò in lui la vocazione al Sacerdozio. Anche l’Amministrazione Comunale, che gli ha dedicato una via del paese, ha voluto ricordare questa eminente figura di villanterese con una lapide commemorativa fatta affiggere, qualche anno fa, sul muro della casa dove il Card. -

SALESIAN PONTIFICAL UNIVERSITY Faculty of Theology Department of Youth Pastoral and Catechetics

SALESIAN PONTIFICAL UNIVERSITY Faculty of Theology Department of Youth Pastoral and Catechetics CATECHISTS’ UNION OF JESUS CRUCIFIED AND OF MARY IMMACULATE Towards a Renewal of Identity and Formation Program from the Perspective of Apostolate Doctoral Dissertation of Ruta HABTE ABRHA Moderator: Prof. Francis-Vincent ANTHONY Rome, 2010-2011 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I want to take this opportunity to express my immense gratitude to God who has sustained, inspired and strengthened me in the entire journey of this study. I have strongly felt his presence and providence. I also want to express my gratitude, appreciation and esteem for all those who have worked and collaborated with me in the realization of this study. My deepest gratitude goes to the first moderator of this study, Prof. Francis-Vincent Anthony, SDB, Director of the Institute of Pastoral Theology in UPS, for having orientated the entire work with great patience and seriousness offering competent suggestions and guidelines and broadening my general understanding. I want to thank him for his essential indications in delineating the methodology of the study, for having indicated and offered necessary sources, for his generosity and readiness in dedicating so much time. If this study has obtained any methodological structure or has any useful contribution the merit goes to him. I esteem him greatly and feel so much pride for having him as my principal guide. Again my most sincere gratitude goes to the second moderator of the study, Prof. Ubaldo Montisci, SDB, former Director of the Catechetical Institute in UPS, for his most acute and attentive observations that enlightened my mind and for having encouraged me to enrich the research by offering concrete suggestions. -

The Post-STURP Era of Shroud Research 1981 to the Present

The Post-STURP Era of Shroud Research 1981 to the Present Presented by BARRIE M. SCHWORTZ Editor and Founder Shroud of Turin Website www.shroud.com President, STERA, Inc. © 1978-2013 STERA, Inc. 4 1 The Post-STURP Era of Shroud Research 1981 to the Present LECTURE 4 A Review of the “Bleak" Years 2 A Review of the “Bleak” Years After the radiocarbon dating results were released, most Shroud research worldwide came to a complete halt. Many qualified researchers simply walked away, accepting that the cloth was medieval. Others, who were not convinced by the dating, quietly continued their work. It would take another 12 years before any significant evidence would come to light that could credibly challenge the medieval results (see Lecture #3 - The 1988 Radiocarbon Dating and STURP). During that time, many theories were proposed as to why the results were inconsistent with the other scientific and historical evidence. These were all tested and eventually discarded, since none of them proved to be credible. In this lecture we will review some of those theories and the events that occurred during that “bleak” period in Shroud research. 3 After the 1988 Radiocarbon Dating October 13, 1988: (Thursday) At a press conference held in Turin, Cardinal Ballestrero, Archbishop of Turin, makes an official announcement that the results of the three laboratories performing the Carbon dating of the Shroud have determined an approximate 1325 date for the cloth. At a similar press conference held at the British Museum, London, it is announced that the Shroud dates between 1260 and 1390 AD. -

Called to Be Fishers of Men

Fifth Grade: Lesson One Called to be Fishers of Men Lesson Objective: Students will be able to Lesson Assessment: Students will identify that define the term “vocation” through reading the first disciples were called by Jesus to be the call of the first disciples. “fishers of men,” and that we are all called by God for a particular reason or mission. Lesson Materials: Lesson Outline: • Students’ religion Opening Prayer Say: Heavenly Father, You made each and every one of notebooks (1 min) us to be unique and to carry out a unique mission in this • Copies of world. Help us learn more today about how You call Mark 1: 16-20 and us to follow Your Son Jesus as we learn about how He Luke 5:1-11 activity called His first disciples to follow Him. We hope to do pages for each Your will in each and every moment of our lives, as we student pray together: Our Father who art in heaven …. Amen. • Pencils • Markers • Overhead projector (optional) Assessing Prior Determine what your students know about the • Venn Diagram Knowledge apostles. transparency (3 min) (optional) Say: Today we are going to talk about Jesus’ apostles. We know that Jesus had 12 apostles, but how many of them can we name? Have a student volunteer write the names of 12 apostles on the board as the other students answer: Simon Peter, Andrew, James, John, Philip, Bartholomew, Thomas, Matthew, James, Judas/ Thaddaeus, Simon the Zealot, Judas Iscariot. Ask the students to say something they know about the apostle who they name. -

FR. GIUSEPPE QUADRIO Theology Teacher and Master of Life

FR. GIUSEPPE QUADRIO Theology Teacher and Master of Life Translation by John Rasor of Remo Bracchi (ed.), Don Giuseppe Quadrio: Docente di Teologia e Maestro di Vita (Rome, LAS 1989), pp. 9-22. These are the proceedings of a 1989 symposium on Fr. Quadrio at the Salesian Pontifical University in Rome. Presentation Fr. Giuseppe Quadrio spent the last fourteen years of his brief and intensive life as a teacher of dogmatic theology in the Theology Department of what was then the Salesian Pontifical Athenaeum of Turin (now Salesian Pontifical University in Rome). He was also chairman of the Department (from 1954 to 1959), up to the time his illness forced his retirement. Teaching theology was the main job given him, and he consecrated his best energies to that, with great seriousness and dedication, bringing to fruition what he had matured in the years of preparation for this task. But more than an assignment or a duty, he always saw a privileged and unique mission. He pushed himself to make an authentic existential synthesis of study, teaching and life; of his study and his life; of theological investigation and contemporary reality; of its problems and challenges. For the students, this was – as numerous testimonies demonstrate – the most important and eloquent lesson of Fr. Quadrio: doing theology with gaze turned with constant attention to those hearing the doctrine, to the students in front of him as well as those far off, but no less important, men of today with their conditionings and culture. He succeeded above all in “doing theology” in the crucible of his own life. -

Lord´S Prayer Catholic.Net

Lord´s Prayer Catholic.net Pope Francis’ remarks on the “wrong” translation of the Lord’s Prayer in a TV show hosted by the Italian Bishops’ Conference’s TV2000 network are part of a wider debate that has taken place in Italy for over two decades. The Pope said that the words “non ci indurre in tentazione” – “Do not lead us into temptation,” in the English version – are not correct, because, he said, God does not actively lead us into temptation. The Pope also praised a new translation operated by the French Bishops’ conference. The new French translation is “et ne nous laisse pas entrer in tentationI” – “let us not enter into temptation.” It replaces the previous translation “ne nous soumets pas à la tentation” – “do not submit us to temptation.” It is worth noting that St. Thomas Aquinas considered the question of whether God leads men “into temptation” in a commentary he wrote on the Our Father. The saint, and Doctor of the Church, concluded that “God is said to lead a person into evil by permitting him to the extent that, because of his many sins, He withdraws His grace from man, and as a result of this withdrawal man does fall into sin.” The Pope’s intent seems to be to emphasize that God’s active will does not “tempt” men, that, instead, the permissive will of God allows people to be tempted because of their sinfulness. This is the emphasis of the French translation. The theological context is complex, but certainly the Pope has not intended to deny the theological and scriptural sense in which God allows, or permits, temptation. -

Weekend Mass Intentions: St. Brigid' Church

Weekend Mass Intentions: Mon 4th 10am: Eoghan Kelly 7pm: Laurance &Bridget Bolger St. Brigid’ Church Tues 5th 10am: Noreen Carney, 7pm: Bridget Doyle, 6pm: Alec & Kathleen Sweeney Months Mind - John Osborne Tuesday 5th January in St. Raphael’s at 7pm 11am: Special intention Wed 6th 8am Eileen & Henry Gunn 10am: Poppie Guinan 12pm PJ O’ Sullivan 7pm: Sean Healy St. Patrick’s Church: Thur 7th 10am: John Finan 7pm: Catherine Bell Saturday Fri 8th 10am: Special Intention, David Joyce 7pm: Kevin O’Sullivan Priests of the Parish: Parish Office: Office hours Mon - Fri 9am - 1pm.(Closed Wednesday) 6.30pm: Ellen Kelly Sat 9th 10am: Louis & Elizabeth Maher Fr. Paul Taylor P.P. tel 6275874 Sunday Contact Details: 01 6288827 / 0858662255 The Feast of the Epiphany is a Holy Day of Obligation and is known as Little Christmas (Nollaig Fr.Kevin Doherty C.C. tel: 5031429 8.30am: Nancy Fahy Ná mBan). 'The Epiphany is the manifestation of Jesus as Messiah of Israel, Son of God and Sav- Fr. Brian McKittrick C.C. tel: 6288827 email: [email protected] Parish website: www.celstra.ie 9.30am: Margaret Hill iour of the world. The great feast of Epiphany celebrates the adoration of Jesus by the wise Sacristy: 0858662255 Information about Baptisms ring 085 8662255 11am: Janie & Thomas Burke Fr. Douglas Zaggi P.C. tel: 6012303 men (magi) from the East, together with his Baptism in the Jordan and the wedding feast at 12.30pm: Dick Lawlor Cana in Galilee. In the magi, representatives of the neighbouring pagan religions, the Gospel The Schools of the Parish begin their new term on the Feast of the Planned giving amount will be given next week 7pm: Kitty Slaughter sees the first-fruits of the nations, who welcome the good news of salvation through the Incar- Epiphany January 6th. -

Salvationday\Salvationday.Txt Friday, June 07, 2013 1:28 PM

C:\salvationday\salvationday.txt Friday, June 07, 2013 1:28 PM Salvation Day: The Immortality Device A Novel by T.L. Winslow (C) Copyright 2000. All Rights Reserved. In accordance with the International Copyright Convention and U.S. federal copyright statutes, permission to adapt, copy, excerpt, whole or in part in any medium, or to extract characters for any purpose whatsoever is herewith expressly withheld. No part of this book may be reproduced in any manner whatsoever without the prior written permission of the author, except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles or reviews. For information, apply to copyright holder. This novel is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents either are the products of the author's imagination or are used fictitiously, and any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events, or locales is entirely coincidental. FF Preface It is the year 2005. A major world corporation discovers "quantum psycho-organic hologram technology" (Q-Psohot, pronounced "Q so hot") which promises a true "immortality -1- C:\salvationday\salvationday.txt Friday, June 07, 2013 1:28 PM device", a way for a person to preserve his "design" for later "resurrection". It is not long before top scientists begin to believe that the Shroud of Turin is a Q-Psohot of Jesus Christ, and top management makes an irrevocable and fatal decision. Using the relatively hectic scene in Turin a year before the XXth Winter Olympics to stage a stealth commando raid they steal the Shroud, with inside help. The company's scientists, led by the discoverer Dr. -

Shroud News Issue #90 August 1995

A NEWSLETTER ABOUT RESEARCH ON THE HOLY SHROUD OF TURIN published in Australia for Worldwide circulation edited by REX MORGAN, Author of several books on the Shroud Issue Number 90 AUGUST 1995 SPECIAL EDITION TURIN ANNOUNCES 1998 EXPOSITION The Holy Shroud on display in Turin in 1978 [Pic: Rex Morgan] 2 SHROUD NEWS No 90 (August 1995) EDITORIAL One might have thought, and perhaps those readers who know my mindset would have expected, that the 90th edition of Shroud News would be a celebratory, bumper issue. I am writing this in September as the production of the August issue was delayed and I so have rescheduled its content so that I can bring you this small hurried edition as quickly as possible. What better celebration of the 90th issue could there be than the very welcome and exciting official news that the Shroud of Turin will be put on exhibition in 1998 and again in 2000. Like many other people, I have taken it as a foregone conclusion for many years that an exposition would have to take place in 1998, the 100th anniversary of the first photographs which have led us for a century to study this phenomenon, not to mention the 500th anniversary of the consecration of the St John's Cathedral in Turin, a more local matter but nevertheless of great significance in the life of Turin. That the Pope and the Cardinal Archbishop have determined to do this twice within three years is a remarkable decision. The dates are fixed: 18 April to 31 May 1998 and 29 April to 11 June 2000. -

A Theological Basis for Sindonology & Its Ecumenical Implications

A theological basis for sindonology & its ecumenical implications* by Rev. Albert R. Dreisbach** Collegamento pro Sindone Internet – December 2001 © All right reserved*** ABSTRACT After presenting a theological basis for sindonology as valid and significant field for continuing study, the author examines its ecumenical implications and offers concrete proposals for future cooperative efforts among the Orthodox, Catholic and Protestant families of the Church. Suggested projects range from making out-of-print classics available through internet electronic “libraries” to joint travelling exhibits of art objects owned by various international Holy Shroud organizations. A THEOLOGICAL BASIS FOR SINDONOLOGY The strength of the Shroud is its vividness to history – a vividness that antedates any New Testament writing – and that moves the Word of God into a new visual language. By means of this vivid witness, we see the face and body of the actual historical Jesus and we have our resurrection faith shaken but finally reshaped in a form closer to that of the first disciples.1 Three years ago in the May/June 1998 issue of Shroud Sources carried a report from the March 10 issue of Avvenire of that year in which Mons. Giuseppe Ghiberti, then advisor to Cardinal Giovanni Saldarini, responded to an article from the March issue of Riforma, an Italian Protestant magazine. Several articles in this publication asked the Church to de-emphasize the Shroud fearing that it is “being used as a tool by the Catholic Church to sustain Christian faith on the base of a piece of linen” - a move which was judged to be a “corrupting use of the ‘sacred’”. -

Microbiology Meets Archaeology in a Renewed Quest for Answers

Spring 1996 Science & the shroud Microbiology meets archaeology in a renewed quest for answers • High magnification close-up of a shroud fiber (108k) By Jim Barrett Hoax or holy grail? The argument about the Shroud of Turin spans centuries. No one has proven it is the burial cloth of Jesus of Nazareth, but its haunting image of a man's wounded body is proof enough for true believers. Researchers from the Health Science Center now appear to have the clue to resolve a scientific contradiction: If the shroud is authentic, why does radiocarbon dating indicate that the cloth is no more than about 700 years old? The shroud is unquestionably old. Its history is known from the year 1357, when it surfaced in the tiny village of Lirey, France. Until recent reports from San Antonio, most of the scientific world accepted the findings of carbon dating carried out in 1988. The results said the shroud dated back to 1260- 1390, and thus is much too new to be Jesus' burial linen. Now the date and other shroud controversies are under intense scrutiny because of discoveries by a team led by Leoncio A. Garza-Valdes, MD, adjunct professor of microbiology, and Stephen J. Mattingly, PhD, professor of microbiology. Dr. Garza is a pediatrician from San Antonio, and an archaeologist noted for expertise in pre- Columbian artifacts. Dr. Mattingly, president of the Texas branch of the American Society for Microbiology, is widely respected for his research on group B streptococci and neonatal disease. After months examining microscopic samples, the team concluded in January that the Shroud of Turin is centuries older than its carbon date. -

Table Des Matières

Table des matières Bibliographie 3 Documents sur les Saints Ordres . 3 Fraternité Saint Pie X (FSSPX) . 4 Vatican II, Paul VI et la Crise Liturgique . 4 Magistère Catholique . 4 Magistère post-conciliaire . 5 Mouvement oecuménique . 6 Invalidité des ordinations anglicanes . 6 Projet Pusey et opération Rampolla de réunion des trois branches . 7 La Révolution liturgique anglicane de Cranmer, ses enjeux, son contexte et ses suites . 7 Contre-Eglise, Kabbale, Démonologie, Gnose . 8 Sources de la prétendue Tradition apostolique d’Hippolyte et des autres rites . 8 Travaux depuis 1995 sur l’authenticité de la Tradition apostolique d’Hippolyte . 9 A Documents 19 A.1 Monseigneur TISSIER DE MALLERAIS : Lettre à Avrillé sur la validité du nouveau rite d’ordination (1998) . 19 A.2 FIDELITER : Une compréhension supérieure de la crise de la papauté Entretien avec Mgr Bernard Tissier de Mallerais (mai-juin 1998) . 21 A.3 Michael DAVIES : Annibale Bugnini, l’auteur principal du Novus Ordo . 25 A.4 Maureen DAY : Le nouveau rite des ordinations (Lettre à Monseigneur Fellay, 1995) . 33 A.4.1 Argument pour la Validité Douteuse, en raison d’un Défaut de Forme, de toutes les Versions du Nouveau Rite d’Ordination des Prêtres de 1968/89 . 34 A.4.2 Huit Objections à l’Argumentaire de la Validité douteuse du NRO, avec les réponses à ces Objections . 37 1 A.4.3 L’Argumentaire théologique d’Apostolicae Curae pour l’invalidité des Ordres Anglicans . 42 A.4.4 Conclusion . 46 B Liste des cardinaux (conclave du 18-19 avril 2005) 49 Bibliographie Documents sur les Saints Ordres [1] Coomaraswamy, The Post-Concilar Rite of Holy Orders, Studies in Comparative Religion, Vol.