Sherlock Holmes the Adventure of the Antiquarian’S Niece

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Janny Wurts ______Supporting Membership(S) at US$35 Each = US$______

Address Correction Requested Address CorrectionRequested Convention 2004 2004 Convention World Fantasy Tempe, AZ 85285-6665Tempe, USA C/O LepreconInc. P.O. Box26665 The 30th Annual World Fantasy Convention October 28-31, 2004 Tempe Mission Palms Hotel Tempe, Arizona USA Progress Report #2 P 12 P 1 Leprecon Inc. presents World Fantasy Con 2004 Registration Form NAME(S) _____________________________________________________________ The 30th Annual ADDRESS ____________________________________________________________ World Fantasy Convention CITY _________________________________________________________________ October 28-31, 2004 STATE/PROVINCE _____________________________________________________ Tempe Mission Palms Hotel ZIP/POSTAL CODE _____________________________________________________ Tempe, Arizona USA COUNTRY ____________________________________________________________ EMAIL _______________________________________________________________ Author Guest of Honour PHONE _______________________________________________________________ Gwyneth Jones FAX __________________________________________________________________ Artist Guest of Honor PROFESSION (Writer, Artist, Editor, Fan, etc.) ______________________________________________________________________ Janny Wurts _______ Supporting Membership(s) at US$35 each = US$_________ Editor Guest of Honor _______ Attending Membership(s) at US$_______ each = US$_________ Ellen Datlow _______ Banquet Tickets at US$53 each = US$ _________ Total US$___________ Publisher Guest of Honor _______ Check: -

Table of Contents Vol. 35 No. 3

September 1995 Table of Contents vol. 35 no. 3 M a i n S t o r ie s Locus Looks a t Books 1995 Hugo Awards Winners... 7 - 13- - 21 - 1995 World Fantasy Distillations: Short Fiction Reviews by Gary K. Wolfe: Reviews by Mark R. Kelly: The Time Ships, Stephen Baxter; Bloodchild: Awards Nominations .............. 7 Asimov’s 11/95; F&SF 8/95; Analog 11/95; Inter Novellas and Stories, Octavia E. Butler; How to Lou Aronica Moves to Avon.... 8 zone 7/95; Omni Online 7/95; Omni Online 8/95. Save the World, Charles Sheffield, ed.; To Write Like a Woman: Essays in Feminism and Sci Manchester vs. Savoy: - 17- ence Fiction, Joanna Russ; Superstitious, R.L. The Latest Round..................... 8 Reviews by Russell Letson: Stine; The Horror at Camp Jellyjam, R.L. Stine; Pocket Does McIntyre The Year’s Best Science Fiction, Twelfth An The Dream Cycle of H.P. Lovecraft: Dreams of nual Collection, Gardner Dozois, ed ; Anatomy Terror and Death, H.P. Lovecraft; deadrush, Alternate History...................... 8 of Wonder 4, Neil Barron, ed. Yvonne Navarro; SHORT TAKE: Women of Won Clarion 1995; der - The Classic Years: Science Fiction by Women from the 1940s to the 1970s/The Con Clarion Call 1996 .................... 8 C o m p l ete For t hcoming temporary Years: Science Fiction by Women Inland Files for Bankruptcy ...... 9 from the 1970s to the 1990s, Pamela Sargent, Strange Matter Gets Books Thr ough ed. -25- Goosebumps.............................. 9 June 1996 Reviews by Faren Miller: New BDD Trade Imprint ........... 9 See p age 3 6 Alvin Journeyman, Orson Scott Card; Expira Future Book Sales Bright......... -

Loscon 34 Program Book

LosconLoscon 3434 WelcomeWelcome to the LogbookLogbook of the “DIG”“DIG” LAX Marriott November 23 - 25, 2007 Robert J. Sawyer Author Guest Theresa Mather Artist Guest Capt. David West Reynolds Fan Guest Dr. James Robinson Music Guest 1 2 Table of Contents Anime .................................. Pg 68 Kids’ Night Out ..................... Pg 63 Art Show .............................. Pg 66 Listening Lounge .................. Pg 71 Awards Masquerade .......................... Pg 59 Evans-Freehafer ................ Pg 56 Members List ................. Pg 75-79 Forry ................................. Pg 57 Office / Lost & Found .......... Pg 71 Rotsler .............................. Pg 58 Photography/Videotape Policies .... Pg 70 Autographs .......................... Pg 73 Programming Panels ....... Pg 38-47 Bios Regency Dancing .................. Pg 62 Author Guest of Honor .........Pg 8-11 Registration .......................... Pg 71 Artist Guest of Honor ........ Pg 12-13 Room Parties ........................ Pg 63 Music Guest of Honor ........ Pg 16-17 Security Fan Guest of Honor ................. Pg 14 Rules & Regulations ..... Pg 70,73 Program Guests ........... Pg 30-37 No Smoking Policy ............. Pg 73 Blood Drive ........................... Pg 53 Weapons Policy ........... Pg 70,73 Chair’s Message .................. Pg 4-5 Special Needs ....................... Pg 60 Children’s Programming ........ Pg 68 Special Stories Committee & Staff ............. Pg 6-7 Peking Man .................. Pg 18-22 Computer Lounge ............... -

Questing Feminism: Narrative Tensions and Magical Women in Modern Fantasy

University of Rhode Island DigitalCommons@URI Open Access Dissertations 2018 Questing Feminism: Narrative Tensions and Magical Women in Modern Fantasy Kimberly Wickham University of Rhode Island, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.uri.edu/oa_diss Recommended Citation Wickham, Kimberly, "Questing Feminism: Narrative Tensions and Magical Women in Modern Fantasy" (2018). Open Access Dissertations. Paper 716. https://digitalcommons.uri.edu/oa_diss/716 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@URI. It has been accepted for inclusion in Open Access Dissertations by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@URI. For more information, please contact [email protected]. QUESTING FEMINISM: NARRATIVE TENSIONS AND MAGICAL WOMEN IN MODERN FANTASY BY KIMBERLY WICKHAM A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN ENGLISH UNIVERSITY OF RHODE ISLAND 2018 DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY DISSERTATION OF KIMBERLY WICKHAM APPROVED: Dissertation Committee: Major Professor Naomi Mandel Carolyn Betensky Robert Widell Nasser H. Zawia DEAN OF THE GRADUATE SCHOOL UNIVERSITY OF RHODE ISLAND 2018 Abstract Works of Epic Fantasy often have the reputation of being formulaic, conservative works that simply replicate the same tired story lines and characters over and over. This assumption prevents Epic Fantasy works from achieving wide critical acceptance resulting in an under-analyzed and under-appreciated genre of literature. While some early works do follow the same narrative path as J.R.R. Tolkien’s The Lord of the Rings, Epic Fantasy has long challenged and reworked these narratives and character tropes. That many works of Epic Fantasy choose replicate the patriarchal structures found in our world is disappointing, but it is not an inherent feature of the genre. -

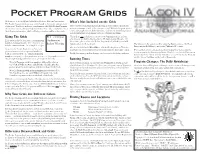

Pocket Program Grids

Pocket Program Grids Welcome to L.A.con IV, the 2006 World Science Fiction Convention! What’s Not Included on the Grids The Pocket Program Grids are your official guide to the events and functions of this year’s Worldcon, and are a complement to the 2006 Pocket Program The Pocket Program Grids include all items as of press time scheduled by that you have received in your registration materials. Take a moment to read main programming as well as the contents of our Children’s Program, special the following information, which will help you understand how they work. events, autograph sessions, kaffeeklatsches, readings, our main film program and special interest programming such as costuming and filking. Using The Grids 911 (3:00pm) The grids do not include the contents of our Gaming program and the schedules for the Anime Room and the SF Asian Action Theatre. For Each entry in the Grids features a program item Underwater these items, please refer to the Pocket Program book, which feature indi- number and program title. The entry may also Basket Weaving vidual sections for these events. The Marriott is the easiest; we’ll be using the Salon rooms for the Blood include a time revision. An example is at right. Drive and the Gold Key rooms for the Children’s SF contest. Also not included is the Blood Drive, which will take place on Thursday As we put the Pocket Program together, each and Friday (as of press time); please see posted signs for time and location. If you get lost or have any questions about finding your way around the program item received a sequential number to facilities, stop by the Information Desks. -

Program Book, As Appropriate

ConGregate 4 / DeepSouthCon 55 July 14-16, 2017 ANSWER THE CALL TO VENGEANCE The Manticore Ascendant Series Continues Travis Long has risen from humble begin- nings to become one of the Royal Manti- coran Navy’s most valuable assets. Twice he’s saved the RMN, but now he faces his greatest challenge yet, one that will test his mettle as an officer and as a man of honor. Vengeance is calling—and Travis Uriah Long is willing and able to answer! The newest installment in the Manticore Ascendant series from New York Times best-selling authors David Weber and Timothy Zahn and Honorverse expert Thomas Pope. Explore the Honorverse Coming through the Manticore March Ascendant series! 2018 Praise for the Manticore Ascendant series: “The plotting is as solid as ever, with smaller scenes building to an explosive, action-packed crescendo . .” —Publishers Weekly “Like Robert A. Heinlein and Orson Scott Card, Weber and Zahn are telling a story about a teenage char- acter but writing for readers of all ages.” —Booklist “[T]his astronautical adventure is filled with . intrigue and political drama.” —Publishers Weekly Find sample chapters for all Baen Books at www.baen.com. For more information, sign up for our newsletters at: http://www.baen.com/newsletter_signup. Table of Contents Statement on Inclusion ............................................ 1 From the Con Chair ........................................................ 1 Convention Staff ......................................................... 2 Harassment Policy ................................................ -

Fiction & Fantasy Digital Collection - Science Fiction & Fantasy Publications

University of South Florida Scholar Commons Digital Collection - Science Fiction & Fantasy Digital Collection - Science Fiction & Fantasy Publications 2-1-1992 SFRA ewN sletter 194 Science Fiction Research Association Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarcommons.usf.edu/scifistud_pub Part of the Fiction Commons Scholar Commons Citation Science Fiction Research Association, "SFRA eN wsletter 194 " (1992). Digital Collection - Science Fiction & Fantasy Publications. Paper 137. http://scholarcommons.usf.edu/scifistud_pub/137 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Digital Collection - Science Fiction & Fantasy at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Digital Collection - Science Fiction & Fantasy Publications by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The SFRA Review Published ten times a year for the Science Fiction Research Association by Alan Newcomer, Hypatia Press, Eugene, Oregon. Copyright © 1992 by the SFRA. Editorial correspondence: Betsy Harfst, Editor, SFRA Review, 2357 E. Calypso, Mesa, AZ 85204. Send changes of address and/or inquiries concerning subscriptions to the Treasurer, listed below. Note to Publishers: Please send fiction books for review to: Robert Collins, Dept. of English, Florida Atlantic University, Boca Raton, FL 33431-7588. Send non-fiction books for review to Neil Barron, 1149 Lime Place, Vista, CA 92083. Juvenile-Young Adult books for review to Muriel Becker, 60 Crane Street, Caldwell, NJ -

The Cambridge Companion to Fantasy Literature Edited by Edward James and Farah Mendlesohn Frontmatter More Information

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-42959-7 - The Cambridge Companion to Fantasy Literature Edited by Edward James and Farah Mendlesohn Frontmatter More information the cambridge companion to fantasy literature Fantasy is a creation of the Enlightenment, and the recognition that excitement and wonder can be found in imagining impossible things. From the ghost stories of the Gothic to the zombies and vampires of twenty-first-century popular lit- erature, from Mrs Radcliffe to Ms Rowling, the fantastic has been popular with readers. Since Tolkien and his many imitators, however, it has become a major publishing phenomenon. In this volume, critics and authors of fantasy look at its history since the Enlightenment, introduce readers to some of the different codes for the reading and understanding of fantasy, and exam- ine some of the many varieties and subgenres of fantasy; from magical realism at the more literary end of the genre, to paranormal romance at the more pop- ular end. The book is edited by the same pair who produced The Cambridge Companion to Science Fiction (winner of a Hugo Award in 2005). A complete list of books in the series is at the back of the book © in this web service Cambridge University Press www.cambridge.org Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-42959-7 - The Cambridge Companion to Fantasy Literature Edited by Edward James and Farah Mendlesohn Frontmatter More information © in this web service Cambridge University Press www.cambridge.org Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-42959-7 - The Cambridge Companion to Fantasy -

The World Fantasy Convention 1996

The World Fantasy Convention 1996 Program & Schedule of Events Cafe Cthulhu is hidden. Cafe Cthulhu is located behind the bar. Cafe Cthulhu is haunted. Cafe Cthulhu is haunted by the spirit of the spoken word. Readings every half-hour! Cafe Cthulhu Weekend hours: Thursday 5pm till Midnight Friday 10am till 8:30pm and also 11PM till 1:30am Saturday 10am till 1:30am Sunday 10am till 7pm Cafe Cthulhu open Mike: Thursday 1 0:30pm till Midnight Sunday 5:30pm till 7pm Secret Map to Cafe Cthulhu Registration Hotel World Fantasy Convention 1996 The Many Faces of Fantasy Guests ofjjonor Katherine Kurtz Joe R. Lansdale Ron Walotsky Ellen Asher Toastmaster Brian Lumley Page 1 Table of Contents Introduction................................................................ 3 Event Area Map.......................................................... 4 Schedule of Events............................................... 5-11 Dealers Room Map.................................................. 12 Dealer Listing........................................................... 13 1996 Award Nominees...................................... 14-15 Previous Winners................................................ 16-21 Art Show Artists Listing............................................. 22 Membership List..................................................23-27 The Shadow over Schaumburg................................28 World Fantasy Convention 1996 Pocket Program is copyright© 1996 by the 1996 World Fantasy Convention. Cover art copyright © by Ron Walotsky. All rights reserved. -

Saturday's Schedule

Loscon 2012 Program Schedule - Saturday Day/Time Title Description Panelists Room Sat 10:00 Exploring Space What are our options for future space Michael Siladi Marquis 1 exploration? What should we be doing? Timothy Cassidy- Where should we be going? How can Curtis individuals get involved? Should it be Arthur Bozlee government sponsored or come from Suzi Casement the private sector? Eric Choi Sat 10:00 A Quiet Place To Does where you write matter? How Alan White Marquis 3 Write about whether or not you face a David Gerrold window? Authors will talk about how Richard Dean Starr they set up their writing spaces – a Cecil Castellucci separate office, the living room couch, the dining room table? – what's in the room, what they listen to, and what they wear (if they wear anything at all). Sat 10:00 Star Wars – 35 Hard to believe but it’s been 35 years Craig Miller Marquis 4 Years Later since release of the original Star Wars. Shawn Crosby What was the movie world like back Regina Franchi then and what changes happened Chris Butler because of Star Wars? Yvonne Penney Lloyd Penney Sat 10:00 What If What effects would there be on society Jacqueline Chicago Superpowers Were if there really were people with Monahan Real? superpowers? Would government's just James Hay let superheroes act? Would near Edward L. Green absolute power corrupt? Would the Buzz Dixon existence of superheroes ultimately Kenn Bates bring forth supervillains? Or would Robert N. Skir there only be supervillains? What toll (or benefit) would the world see from years or decades of superpowered derring-do? Sat 10:00 Writers & The Writers and Illustrators of the Joni Labaqui Dallas Illustrators Of The Future contest has been going on for Future quite a few years and many budding science fiction and fantasy writers and artists have entered, won, and gone on to make professional sales. -

Barbara Hambly Papers

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/c84x58mb No online items Barbara Hambly papers Finding aid prepared by Julia D. Ree, Principal Cataloger, Eaton Collection. Special Collections & University Archives The UCR Library P.O. Box 5900 University of California Riverside, California 92517-5900 Phone: 951-827-3233 Fax: 951-827-4673 Email: [email protected] URL: http://library.ucr.edu/libraries/special-collections-university-archives © 2013 The Regents of the University of California. All rights reserved. Barbara Hambly papers MS 162 1 Descriptive Summary Title: Barbara Hambly papers Date (inclusive): 1968-2008, undated Date (bulk): 1982-1989 Collection Number: MS 162 Creator: Effinger, George Alec Creator: Hambly, Barbara Creator: Niemand, O. Extent: 23.5 linear feet(22 boxes) Repository: Rivera Library. Special Collections Department. Riverside, CA 92517-5900 Abstract: This collection contains novels and short stories written or edited by Barbara Hambly, an American science fiction, fantasy, and mystery writer. Also includes novels and short stories written by George Alec Effinger, an American science fiction writer, and short stories written by O. Niemand, Effinger's best known pseudonym. Formats include manuscripts, sketches, diaries, notes, story fragments, poems, correspondence, and other material. Languages: The collection is in English. Access This collection is open for research. Part of the collection is unprocessed, please contact Special Collections & University Archives regarding the availability of these materials for research use. Publication Rights Copyright has not been assigned to the University of California, Riverside Libraries, Special Collections & University Archives. Distribution or reproduction of materials protected by copyright beyond that allowed by fair use requires the written permission of the copyright owners. -

Final Paper for MA Degree on Vampires

Final Paper for MA Degree In English On Vampires: An exploration of the vampire as a literary character Helga Ósk Hreinsdóttir May 2021 University of Iceland School of Humanities Faculty of Languages and Culture On Vampires: An exploration of the vampire as a literary character MA degree in English Helga Ósk Hreinsdóttir Kt.: 120682-4079 Supervisor: Úlfhildur Dagsdóttir Maí 2021 2 Summary This thesis is an exploration of the vampire as a literary character. Of how the figure of the vampire has become a contemporary cultural icon. In part one of this exploration the genesis of the vampire as a literary character is considered along with its main fictional influences. Following that the thesis considers the question of what the essence of the vampire is and its diverse representations. This brings the evaluation to the inherent duality of the vampire and its mutability as a literary character within diverse fictional genres. The second part of this thesis is an analysis of three distinct vampire character varieties. The three classifications are the vampire as lover, Dracula derivations and the born vampire. The vampire as lover is a recurrent character in paranormal romance novels and Dracula derivations have become a genre of itself within vampire literature. The born vampire is a relatively new concept that seems to float between genres without typifying any of them. Two novels were selected for each type and the paper concludes with an analysis of them. 3 Table of Contents Introduction ..................................................................................................................... 5 Part I: Aspects of the Vampire ........................................................................................... 8 1.2 On Character .................................................................................................................... 13 1.2.1 The Sympathetic Vampire .................................................................................................................