Mahi-The-Story-Of-India-S-Most-S.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Captain Cool: the MS Dhoni Story

Captain Cool The MS Dhoni Story GULU Ezekiel is one of India’s best known sports writers and authors with nearly forty years of experience in print, TV, radio and internet. He has previously been Sports Editor at Asian Age, NDTV and indya.com and is the author of over a dozen sports books on cricket, the Olympics and table tennis. Gulu has also contributed extensively to sports books published from India, England and Australia and has written for over a hundred publications worldwide since his first article was published in 1980. Based in New Delhi from 1991, in August 2001 Gulu launched GE Features, a features and syndication service which has syndicated columns by Sir Richard Hadlee and Jacques Kallis (cricket) Mahesh Bhupathi (tennis) and Ajit Pal Singh (hockey) among others. He is also a familiar face on TV where he is a guest expert on numerous Indian news channels as well as on foreign channels and radio stations. This is his first book for Westland Limited and is the fourth revised and updated edition of the book first published in September 2008 and follows the third edition released in September 2013. Website: www.guluzekiel.com Twitter: @gulu1959 First Published by Westland Publications Private Limited in 2008 61, 2nd Floor, Silverline Building, Alapakkam Main Road, Maduravoyal, Chennai 600095 Westland and the Westland logo are the trademarks of Westland Publications Private Limited, or its affiliates. Text Copyright © Gulu Ezekiel, 2008 ISBN: 9788193655641 The views and opinions expressed in this work are the author’s own and the facts are as reported by him, and the publisher is in no way liable for the same. -

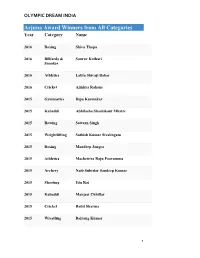

Arjuna Award Winners from All Categories Year Category Name

OLYMPIC DREAM INDIA Arjuna Award Winners from All Categories Year Category Name 2016 Boxing Shiva Thapa 2016 Billiards & Sourav Kothari Snooker 2016 Athletics Lalita Shivaji Babar 2016 Cricket Ajinkya Rahane 2015 Gymnastics Dipa Karmakar 2015 Kabaddi Abhilasha Shashikant Mhatre 2015 Rowing Sawarn Singh 2015 Weightlifting Sathish Kumar Sivalingam 2015 Boxing Mandeep Jangra 2015 Athletics Machettira Raju Poovamma 2015 Archery Naib Subedar Sandeep Kumar 2015 Shooting Jitu Rai 2015 Kabaddi Manjeet Chhillar 2015 Cricket Rohit Sharma 2015 Wrestling Bajrang Kumar 1 OLYMPIC DREAM INDIA 2015 Wrestling Babita Kumari 2015 Wushu Yumnam Sanathoi Devi 2015 Swimming Sharath M. Gayakwad (Paralympic Swimming) 2015 RollerSkating Anup Kumar Yama 2015 Badminton Kidambi Srikanth Nammalwar 2015 Hockey Parattu Raveendran Sreejesh 2014 Weightlifting Renubala Chanu 2014 Archery Abhishek Verma 2014 Athletics Tintu Luka 2014 Cricket Ravichandran Ashwin 2014 Kabaddi Mamta Pujari 2014 Shooting Heena Sidhu 2014 Rowing Saji Thomas 2014 Wrestling Sunil Kumar Rana 2014 Volleyball Tom Joseph 2014 Squash Anaka Alankamony 2014 Basketball Geetu Anna Jose 2 OLYMPIC DREAM INDIA 2014 Badminton Valiyaveetil Diju 2013 Hockey Saba Anjum 2013 Golf Gaganjeet Bhullar 2013 Athletics Ranjith Maheshwari (Athlete) 2013 Cricket Virat Kohli 2013 Archery Chekrovolu Swuro 2013 Badminton Pusarla Venkata Sindhu 2013 Billiards & Rupesh Shah Snooker 2013 Boxing Kavita Chahal 2013 Chess Abhijeet Gupta 2013 Shooting Rajkumari Rathore 2013 Squash Joshna Chinappa 2013 Wrestling Neha Rathi 2013 Wrestling Dharmender Dalal 2013 Athletics Amit Kumar Saroha 2012 Wrestling Narsingh Yadav 2012 Cricket Yuvraj Singh 3 OLYMPIC DREAM INDIA 2012 Swimming Sandeep Sejwal 2012 Billiards & Aditya S. Mehta Snooker 2012 Judo Yashpal Solanki 2012 Boxing Vikas Krishan 2012 Badminton Ashwini Ponnappa 2012 Polo Samir Suhag 2012 Badminton Parupalli Kashyap 2012 Hockey Sardar Singh 2012 Kabaddi Anup Kumar 2012 Wrestling Rajinder Kumar 2012 Wrestling Geeta Phogat 2012 Wushu M. -

GOVERNMENT of INDIA LAW COMMISSION of INDIA Report No. 275 LEGAL FRAMEWORK: BCCI Vis-À-Vis RIGHT to INFORMATION ACT, 2005 April

GOVERNMENT OF INDIA LAW COMMISSION OF INDIA Report No. 275 LEGAL FRAMEWORK: BCCI vis-à-vis RIGHT TO INFORMATION ACT, 2005 April, 2018 i ii Report No. 275 LEGAL FRAMEWORK: BCCI vis-à-vis RIGHT TO INFORMATION ACT, 2005 Table of Contents Chapters Title Pages I Background 1-23 A. A Brief History of Cricket in India 1 B. History of BCCI 3 C. Evolution of the Right to Information 5 (RTI) in India (a) Right to Information Laws in 9 States 1) Tamil Nadu 9 2) Goa 10 3) Madhya Pradesh 12 4) Rajasthan 13 5) Karnataka 14 6) Maharashtra 15 7) Delhi 16 8) Uttar Pradesh 17 9) Jammu & Kashmir 17 10) Assam 18 (b) RTI Movement – social and 19 national milieu II Reference to Commission and Reports 24-30 of Various Committees A. NCRWC Report, 2002 24 B. 179th Report of the Law Commission 26 of India, 2001 C. Report of the Pranab Mukherjee 26 Committee, 2001 D. Report of the Working Group for 27 Drafting of the National Sports Development Bill 2013 E. Lodha Committee Report, 2016 28 iii III Concept of State under Article 12 of the 31-36 Constitution of India - Analysis of the term ‘Other authorities’ IV RTI – Human Rights Perspective 37-55 a. Right to Information as a Human 38 Right - Constitutional position 40 b. Application to Private Entities 44 (i) State Responsibility 45 (ii) Duties of Private Bodies 46 c. Human Rights and Sports 48 V Perusal of the terms “Public Authority” 56-82 and “Public Functions” and “Substantially financed” 1. -

Smith Scripts Australia's Sensational Fi

EEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEE THE HINDU DELHI FRIDAY, AUGUST 2, 2019 SPORT 19 EEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEE Smith scripts Australia’s sensational fightback on absorbing day Broad and Woakes rip through the visitors’ toporder; Anderson suffers calf injury THE ASHES World Cup that England condbest score of the in er Stuart Broad took five for won, was subjected to re nings — in a ninthwicket 86 in 22.4 overs and fellow peated jeers by a partisan partnership of 88. paceman Chris Woakes Agence France-Presse Birmingham crowd. Up until that point it chipped in with three for 58 But he answered the boos seemed England would not on his Warwickshire home Steve Smith marked his first in style with his 24th Test suffer from the absence of ground. Test since completing a 12 century and ninth against James Anderson, England’s But Australia’s total may month ban for his -

Messi, Ronaldo Post Hat Tricks in Big Wins

14 Monday 22nd November, 2010 or sheer theatre, against the called on and deliver five sharp overs ously embarrassed at the end of the first with a set of bowlers who are under MADRID (AP) - Lionel unique backdrop of the Galle Fort, apiece with the new ball at the end of day in Galle, expressing the frustrations pressure and frankly what we have seen Messi scored a hat trick in Fthere was nothing better. A pity the the day. of “a bad day at the office” comment so far this year, suggests that Sri Lanka, Barcelona's record 8-0 rout rain spoilt the event and a possible victo- Little wonder the rumour that a that would have left the captain furious with the decision to mothball Lasith of Almeria, while ry for the West Indies. tight-lipped Kumar Sangakkara was and the coach bemused as the selection Malinga for the World Cup, is a gamble. Cristiano Ronaldo It just wasn’t the Chris Gayle triple unhappy with the bowling attack he was of two bowlers who struggled to make an In his eleven Tests, Nuwan answered with three century that was so remarkable, given for the Test at Galle International. impact once the shine had gone off the Kalusekara has 25 wickets at 34.58 and goals of his own as Real Madrid beat Yahaluweni. It was the spectacular show- He had a right to gripe. It is ball. his last Test was against India in Athletic casing that Test cricket brings to the like a general looking for his In fact, until after lunch on Mumbai almost a year ago. -

The Natwest Series 2001

The NatWest Series 2001 CONTENTS Saturday23June 2 Match review – Australia v England 6 Regulations, umpires & 2002 fixtures 3&4 Final preview – Australia v Pakistan 7 2000 NatWest Series results & One day Final act of a 5 2001 fixtures, results & averages records thrilling series AUSTRALIA and Pakistan are both in superb form as they prepare to bring the curtain down on an eventful tournament having both won their last group games. Pakistan claimed the honours in the dress rehearsal for the final with a memo- rable victory over the world champions in a dramatic day/night encounter at Trent Bridge on Tuesday. The game lived up to its billing right from the onset as Saeed Anwar and Saleem Elahi tore into the Australia attack. Elahi was in particularly impressive form, blast- ing 79 from 91 balls as Pakistan plundered 290 from their 50 overs. But, never wanting to be outdone, the Australians responded in fine style with Adam Gilchrist attacking the Pakistan bowling with equal relish. The wicketkeep- er sensationally raced to his 20th one-day international half-century in just 29 balls on his way to a quick-fire 70. Once Saqlain Mushtaq had ended his 44-ball knock however, skipper Waqar Younis stepped up to take the game by the scruff of the neck. The pace star is bowling as well as he has done in years as his side come to the end of their tour of England and his figures of six for 59 fully deserved the man of the match award and to take his side to victory. -

P16 3 Layout 1

TUESDAY, MARCH 7, 2017 SPORTS ‘Pakistan wins today’ as final passes off peacefully LAHORE: Pakistan yesterday hailed the hand injury. “My good friend Lala (Afridi) successful staging of the Pakistan Super said: ‘If we get to the final you should come League final as a step towards restoring to Lahore’,” Sammy told the crowd. international cricket in the country after a “I am glad I came to experience the deadly attack on the Sri Lankan team in atmosphere here. Even though Peshawar 2009. With nerves jangling after a recent came out on top, cricket was the real win- resurgence of militant violence, tight secu- ner in Lahore,” he added. rity blanketed Lahore’s sold-out Gaddafi Stadium but the game went off peacefully #CRICKETCOMESHOME with Peshawar Zalmi beating Quetta Fans around the country watched the Gladiators by 58 runs. match on giant screens placed in market- Fans held up banners proclaiming places, while many tweeted under the “Pakistan wins today”, reflecting a mood of hashtag #CricketComesHome. defiance. The rest of the Twenty20 tourna- Legendary paceman Wasim Akram ment was played in the United Arab called it a “momentous occasion for Emirates for safety reasons. Pakistan”, while fans at the ground said “Peshawar Zalmi on Sunday may have they had sent the militants a message. won the Pakistan Super League (PSL) but “I felt no fear and I just came to give a the real victory was that of the country, message to terrorists that Pakistanis are which after years of terrorism and turmoil not afraid of their cowardly acts,” said was able to stage a landmark international Mohammad Nauman, who paid $40 for his event in Lahore,” the Express Tribune said. -

Walsh on Record-Breaking Mission

Walsh on record-breaking mission Usually performing the role BY RW MATIDAS first Test at Brisbane, he joined of "workhorse" while bowling fellow West Indies bowlers, his heart out for the West AFTER 110 matches and Wes Hall and Lance Gibbs. to Indies, Walsh was rewarded for 423 wickets, West Indies ace achieve a rare hattrick, while his relentless drive for perfec fastbowler, Courtney Andrew being the first in Test history to tion when he erased Malcolm Walsh, now sets out on a mis complete the feat over two Marshall's tally of 376 as tl1e sion to become Test cricket's innings. highest West Indian Test wick highest wicket-taker when During the fourth Test at et-taker. the frrst of two-match series Sydney, the determined and at During the West Indies disas between the touring West times luckless Walsh became trous 1998-99 tour of South Indies and New Zealand the 12th West Indies bowler to Walsh equalled the starts on December 16 at claim 100 Test wickets. He Africa, record with the fourth ball of his Hamilton. · reached the landmark in his when the home side Walsh needs a· mere 12 wick 29th Test when wicketkeeper, second over opening Test at ets to overtake retired Indian Jeffrey Dujon, accepted a catch batted in the the second day. fast-medium all-rounder Kapil to dismiss centunon, David Johannesburg on wait, Walsh Dev's record tally of 434 Test Boon. After a two-hour to wickets from 131 matches. When India came to the removed Jacques Kallis (53) Interestingly, when Walsh Caribbean for a four Test series re-write the record books. -

Judgment Mr Justice Bean

Case No: HQ10D00267 Neutral Citation Number: [2012] EWHC 756 (QB) IN THE HIGH COURT OF JUSTICE QUEEN'S BENCH DIVISION Royal Courts of Justice Strand, London, WC2A 2LL Date: 26/03/2012 Before : MR JUSTICE BEAN - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - Between : CHRIS LANCE CAIRNS Claimant - and - LALIT MODI Defendant - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - Andrew Caldecott QC and Ian Helme (instructed by Collyer-Bristow) for the Claimant Ronald Thwaites QC and Jonathan Price (instructed by Fladgate LLP) for the Defendant Hearing dates: 5-9, 12, 14 and 16 March 2012 - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - Judgment Mr Justice Bean: 1. The Claimant, who was born in 1970, is a well known New Zealand cricketer who won 62 Test caps and captained his country in 7 Test matches. When the shorter formats of the game are included he represented New Zealand on 267 occasions. He is one of only a handful of men who have reached the “all rounders’ double” of 200 wickets and 3000 runs in international cricket. His last appearance for New Zealand in a Test match was in June 2004 and in a one day international in January 2006. 2. The Defendant was formerly the Chairman and Commissioner of the Indian Premier League (IPL) and Vice-President of the Board of Cricketing Control for India (BCCI). He was suspended from these positions in April 2010 and removed from them in September 2010. The IPL operates Twenty20 competitions in India which attract an enormous following and have changed the face of cricket. At the time of the events in question Mr Modi was a very powerful figure in world cricket. He is now resident in England. -

Page 01 Dec 31.Indd

ISO 9001:2008 CERTIFIED NEWSPAPER Opec output hits six-month low on Libya Business | 17 Wednesday 31 December 2014 • 9 Rabial I 1436 • Volume 19 Number 6296 www.thepeninsulaqatar.com [email protected] | [email protected] Editorial: 4455 7741 | Advertising: 4455 7837 / 4455 7780 Stop closure of Deputy Emir awards camel race winners OPINION Gulf and the petrol stations, oil crisis s it the Ibegin- ning of says civic body the end or end of the begin- ning? Ten facilities already shut down Whatever inter- DOHA: The Central Municipal offered various services in just a preta- Council (CMC) yesterday raised small place — services like car- tions and Dr Khalid Al Jaber the issue of shortage of petrol wash and tyre change. analyses stations and urged the civic Then, there were people who experts might offer on the ministry to stop shutting down come to the petrol station to buy steep decline in oil prices, these stations, especially in refreshments and transparent there is no doubt that the densely populated areas. cooking gas cylinders. current crisis is causing The CMC said there was a need Al Hajri suggested that the alarm about the future of to conduct studies to assess the government come out with some this most important stra- requirement of petrol stations in solutions like moving the above tegic commodity and its different localities and take meas- services. “A petrol station should impact on the Gulf States in ures to increase their number. be reserved only for refuelling The Deputy Emir H H Sheikh Abdullah bin Hamad Al Thani awarding the winner of the Founder Sheikh particular. -

Pakistan Take Charge of Decisive Test

The Island, Tuesday 31st January, 2006 India poses biggest threat to hosts at Youth World Cup by Rex Clementine host all Sri Lanka’s first round Kaif beat the hosts to win the tions from the supporters put games. 2000 edition of the competi- the young players under Neighbour India poses the Two teams will qualify for tion at the SSC. additional pressure? biggest challenge to hosts Sri the quarter-finals of the com- Sri Lanka played India in “Conditions here are Lanka in the Under-19 Cricket petition from each group and the Afro-Asian Cup last year going to help us obviously World Cup that gets under- if Sri Lanka go through they in India and were beaten in and it’s an advantage. With way next week in Colombo. will probably meet either the the final, but apparently have expectations being so high, Sri Lanka’s captain Angelo West Indies, Australia or addressed key areas that did- the pressure can build, but Mathews, coach Sumithra South Africa. n’t go right for them in that looking positively it will help Warnakulasuriya and manag- “The Indian game is going tournament. us to do even better,” er Ashley de Silva addressed to be the toughest for us. They “During the Afro-Asia Mathews said. the media in Colombo, yester- are a good side, but having Cup fielding was our main The hosts are also the most day. said that, we’ll be approach- concern. We have done a lot prepared team in the compe- Sri Lanka are drawn in ing all games with the same of hard work towards rectify- tition having toured Pakistan, Group ‘C’ in the two week level of intensity,” Mathews ing the shortcomings,” Bangladesh and England. -

A Word from Our President …

ELAIDE AD ffal the BuBu os allrounder A Word from Our President … Following on last year’s successful The structure of senior coaching by centenary season, we entered this a panel of coaches has worked well first year of our club’s 2nd. Century & a change of policy with regard to with big challenges. The retirement junior administration has already of Ben Johnson left a big hole in the been enforced, allowing the junior A's, creating an opportunity for an captains to be responsible for their aspiring player to stand up, but the captaining on the field. This policy induction of four new young players is now working very smoothly. On a Michael Maurici (513), Rick Francis rotational basis three junior players (514), Adam Lidiard (515) & David have also trained with the seniors Reynolds (516) into our ‘A’ side just each week... demonstrates our thinking for the future... A big Thankyou to all our sponsors Bob Harris for being an important part of our Adelaide Cricket Thanks to a top concerted effort by Club by providing the support to Club President Andrew Ramage and our band of help keep our club competitive. In volunteers who helped to complete particular, the following sponsors the internal painting, we were able deserve to be recognised here for to use the new dressing rooms for their invaluable help this year: the start of the season, & we have ADSTEEL Pty. Ltd. since settled in reasonably well and BAHNERTS STEEL SUPPLIES Pty. Ltd. now feel right at home. You’ll have BONE TIMBER INDUSTRIES SIR RONALD BRIERLEY noticed that the renovations to our MAID OF AUCKLAND HOTEL clubrooms are almost completed NATIONWIDE LABELLING Inside: but we will need some volunteers NICK MEIERS ELECTRICAL to paint the interior, (any interested PORTFOLIO PLANNING SOLUTIONS Coach’s people please contact me!).