31 January 2018

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Zambia 30 September 2017

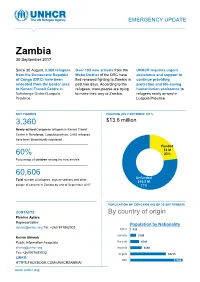

EMERGENCY UPDATE Zambia 30 September 2017 Since 30 August, 3,360 refugees Over 100 new arrivals from the UNHCR requires urgent from the Democratic Republic Moba District of the DRC have assistance and support to of Congo (DRC) have been fled renewed fighting to Zambia in continue providing relocated from the border area past two days. According to the protection and life-saving to Kenani Transit Centre in refugees, more people are trying humanitarian assistance to Nchelenge District/Luapula to make their way to Zambia. refugees newly arrived in Province. Luapula Province. KEY FIGURES FUNDING (AS 2 OCTOBER 2017) 3,360 $13.6 million requested for Zambia operation Newly-arrived Congolese refugees in Kenani Transit Centre in Nchelenge, Luapula province. 2,063 refugees have been biometrically registered Funded $3 M 60% 23% Percentage of children among the new arrivals Unfunded XX% 60,606 [Figure] M Unfunded Total number of refugees, asylum-seekers and other $10.5 M people of concern in Zambia by end of September 2017 77% POPULATION OF CONCERN (AS OF 30 SEPTEMBER) CONTACTS By country of origin Pierrine Aylara Representative Population by Nationality [email protected] Tel: +260 977862002 Other 415 Somalia 3199 Kelvin Shimoh Public Information Associate Burundi 4749 [email protected] Rwanda 6130 Tel: +260979585832 Angola 18715 LINKS: DRC 27398 HTTPS:FACEBOOK.COM/UNHCRZAMBIA/ www.unhcr.org 1 EMERGENCY UPDATE > Zambia / 30 September 2017 Emergency Response Luapula province, northern Zambia Since 30 August, over 3,000 asylum-seekers from the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) have crossed into northern Zambia. New arrivals are reportedly fleeing insecurity and clashes between Congolese security forces FARDC and a local militia groups in towns of Pweto, Manono, Mitwaba (Haut Katanga Province) as well as in Moba and Kalemie (Tanganyika Province). -

ZAMBIA HUMANITARIAN SITUATION REPORT 1 January to 30 June 2018

UNICEF ZAMBIA HUMANITARIAN SITUATION REPORT 1 January to 30 June 2018 Zambia Humanitarian Situation Report ©UNICEF Zambia/2017/Ayisi ©UNICEF REPORTING PERIOD: JANUARY - JUNE 2018 SITUATION IN NUMBERS Highlights 15,425 # of registered refugees in Nchelengue • As of 28 June 2018, a total of 15,425 refugees from the district Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) were registered at (UNHCR, Infographic 28 June 2018) Kenani transit centre in the Luapula Province of Zambia. • UNICEF and partners are supporting the Government of Zambia 79% to provide life-saving services for all the refugees in Kenani of registered refugees are women and transit centre and in the Mantapala permanent settlement area. children • More than half of the refugees have been relocated to Mantapala permanent settlement area. 25,000 • The set-up of basic services in Mantapala is drastically delayed # of expected new refugees from DRC in due to heavy rainfall that has made access roads impassable. Nchelengue District in 2018 • Discussions between UNICEF and the Government are under way to develop a transition and sustainability plan to ensure the US$ 8.8 million continuity of services in refugee hosting areas. UNICEF funding requirement UNICEF’s Response with Partners Funding Status 2018 UNICEF Sector Carry- forward Total Total amount: UNICEF Sector $0.2 m Funds received current Target Results* Target year: $2.5 m Results* Nutrition: # of children admitted for SAM 400 273 400 273 treatment Health: # of children vaccinated against 11,875 6,690 11,875 6,690 measles WASH: # of people provided with access to 15,000 9,253 25,000 15,425 Funding Gap: $6.1 m safe water =68% Child Protection: # of children receiving 5,500 3,657 9,000 4,668 psychosocial and/or other protection services Funds available include funding received for the current year as well as the carry-forward from the previous year. -

Household Food Security and Nutrition in the Luapula Valley, Zambia

22 Household food security and nutrition in the Luapula Valley, Zambia K. Callens and E.C. Phiri Karel Callens is Chief Technical Adviser and Elizabeth C. Phiri is National Project Coordinator for the Improving Household Food Security and Nutrition Project. he Luapula Valley of northern Zambia has significant Improvements in the production of other important food crops T natural resources, and the main road cutting through the were neglected. valley has attracted many people to the area. Of the In the Luapula Valley, rates of chronic malnutrition and population of 207 000, the majority of people live along the micronutrient deficiencies are unacceptably high. Preliminary lake, the lagoon and the river (Figure 1). Fishing is the results from two nutrition surveys carried out in the area in principal economic activity, and agriculture is practised September 1997 and May 1998 indicated that about 65 percent further inland. The diet of most households is based on two of children under five years of age were stunted because of main staples: cassava and maize. As relish people consume fish chronic protein-energy malnutrition, while 3.7 percent were in those areas with access to water resources and a limited wasted during the rainy season and 2.5 percent during the dry number of less abundant and seasonally available food crops season as a result of acute malnutrition. According to a such as sweet potatoes, groundnuts, bambara nuts, cowpeas participatory rural appraisal carried out by the Zambian and beans as well as indigenous and other vegetables. Palm oil Ministry of Agriculture, Food and Fisheries, the Ministry of is also consumed in a few villages where oil-palm trees are Health, the Ministry of Community Development and Social found. -

The Political Ecology of a Small-Scale Fishery, Mweru-Luapula, Zambia

Managing inequality: the political ecology of a small-scale fishery, Mweru-Luapula, Zambia Bram Verelst1 University of Ghent, Belgium 1. Introduction Many scholars assume that most small-scale inland fishery communities represent the poorest sections of rural societies (Béné 2003). This claim is often argued through what Béné calls the "old paradigm" on poverty in inland fisheries: poverty is associated with natural factors including the ecological effects of high catch rates and exploitation levels. The view of inland fishing communities as the "poorest of the poorest" does not imply directly that fishing automatically lead to poverty, but it is linked to the nature of many inland fishing areas as a common-pool resources (CPRs) (Gordon 2005). According to this paradigm, a common and open-access property resource is incapable of sustaining increasing exploitation levels caused by horizontal effects (e.g. population pressure) and vertical intensification (e.g. technological improvement) (Brox 1990 in Jul-Larsen et al. 2003; Kapasa, Malasha and Wilson 2005). The gradual exhaustion of fisheries due to "Malthusian" overfishing was identified by H. Scott Gordon (1954) and called the "tragedy of the commons" by Hardin (1968). This influential model explains that whenever individuals use a resource in common – without any form of regulation or restriction – this will inevitably lead to its environmental degradation. This link is exemplified by the prisoner's dilemma game where individual actors, by rationally following their self-interest, will eventually deplete a shared resource, which is ultimately against the interest of each actor involved (Haller and Merten 2008; Ostrom 1990). Summarized, the model argues that the open-access nature of a fisheries resource will unavoidably lead to its overexploitation (Kraan 2011). -

Full Text Document (Pdf)

Kent Academic Repository Full text document (pdf) Citation for published version Macola, Giacomo (2006) “It Means as If We Are Excluded from the Good Freedom”: Thwarted Expectations of Independence in the Luapula Province of Zambia, 1964-1967. Journal of African History, 47 (1). pp. 43-56. ISSN 0021-8537. DOI https://doi.org/10.1017/S0021853705000848 Link to record in KAR https://kar.kent.ac.uk/7559/ Document Version UNSPECIFIED Copyright & reuse Content in the Kent Academic Repository is made available for research purposes. Unless otherwise stated all content is protected by copyright and in the absence of an open licence (eg Creative Commons), permissions for further reuse of content should be sought from the publisher, author or other copyright holder. Versions of research The version in the Kent Academic Repository may differ from the final published version. Users are advised to check http://kar.kent.ac.uk for the status of the paper. Users should always cite the published version of record. Enquiries For any further enquiries regarding the licence status of this document, please contact: [email protected] If you believe this document infringes copyright then please contact the KAR admin team with the take-down information provided at http://kar.kent.ac.uk/contact.html ‘IT MEANS AS IF WE ARE EXCLUDED FROM THE GOOD FREEDOM’: THWARTED EXPECTATIONS OF INDEPENDENCE IN THE LUAPULA PROVINCE OF ZAMBIA, 1964-1966* BY GIACOMO MACOLA Centre of African Studies, University of Cambridge ABSTRACT: Based on a close reading of new archival material, this article makes a case for the adoption of an empirical, ‘sub-systemic’ approach to the study of nationalist and post- colonial politics in Zambia. -

Environmental Awareness Among Key Actors of Selected Zambian Schools of Nchelenge District in Luapula Province

ENVIRONMENTAL AWARENESS AMONG KEY ACTORS OF SELECTED ZAMBIAN SCHOOLS OF NCHELENGE DISTRICT IN LUAPULA PROVINCE. By Makoba Charles A dissertation submitted to the University of Zambia in partial fulfillment of the Requirements for the award of the degree of Master of Education in Environmental Education. The University of Zambia Lusaka 2014 i DECLARATION I, CHARLES MAKOBA, declare that the dissertation hereby submitted is my own work and it has not previously been submitted for any Degree, Diploma or other qualification at the University of Zambia or any other University. Signed: ………………………………………… Date:…………………………………………… ii APPROVAL This dissertation by Charles Makoba is approved as partial fulfillment of the requirements for the award of the Master of Education (Environmental Education) degree of the University of Zambia. Signed……………………………………….. Date………………………………….. Signed……………………………………….. Date…………………………………... Signed……………………………………….. Date…………………………………… iii COPYRIGHT No part of this dissertation may be reproduced, restored in a retrieval system, transmitted in any form or by any means electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without the prior written permission. iv ABSTRACT There are several environmental conditions that have become areas of major concern at global, regional and national levels both in urban and rural areas. These conditions are as a result of environmental degradation such as deforestation, indiscriminate waste disposal, poor health and sanitation, water pollution and land degradation to mention but a few. Environmental mismanagement affects both human beings and other living organisms in different ways, such as outbreaks of diseases like cholera which is very common in Nchelenge district especially Kashikishi settlement and islands where it has become an annual event. Such diseases could be due to unfriendly environmental practices by the local people, who may probably, have very limited knowledge on how to utilize the environment in a more sustainable manner. -

Am961e00.Pdf

REGIONAL PROJECT FOR INLAND FISHERIES PLANNING, DEVELOPMENT AND MANAGEMENT IN EA-STERN/CENTRAL/SOUTHERN AFRICA (I.F.I.P.) IFIP PRO ECT RAF/87/099-TD/50/93 (En) May 1993 "Our Children Will Suffer": Present Status and Problems of Mweru-Luapula Fisheries and the Need for a Conservation and Management Action Plan Ethiopia Zambia Kenya Zaire Tanzania Burundi Mozambique Rwanda Zimbabwe Uganda Malawi UNITED NATIONS DEVELOPMENT PROGRAMME FOOD AND AGRICULTURE ORGANIZATION OF THE UNITED NATIONS UNDP/FAO Regional Project RAF/87/099-TD/50/93 (En) for Inland Fisheries Planning Development and Management in Eastern/Central/Southern Africa RAF/87/099-TD/50/93 (En) May 1993 "Our Children Will Suffer": Present Status and Problems of Mweru-Luapula Fisheries and the Need for a Conservation and Management Action Plan by B.H.M. Aarnink, C.K. Kapasa and P.A.M. van Zwieten Department of Fisheries Nchelenge, Luapula Province Zambia FOOD AND AGRICULTURE ORGANIZATION OF THE UNITED NATIONS UNITED NATIONS DEVELOPMENT PROGRAMME Bujumbura, May 1993 i The conclusions and recommendations given in this and other reports inthe IFIP project seriesare those considered appropriate at the time of preparation. They maybemodifiedinthelight of furtherknowledge gained at subsequent stages of the Project. The designations employed and the presentation of material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion on the part of FAO or UNDP concerning the legal status ofany country, territory, city orarea, or concerning the determination of its frontiers or boundaries. ii PREFACE The IFIP project started in January 1989 with the main objective of promoting a more effective and rational exploitation of the fisheries resources of major water bodies of Eastern, Central and Southern Africa. -

Chiefdoms/Chiefs in Zambia

CHIEFDOMS/CHIEFS IN ZAMBIA 1. CENTRAL PROVINCE A. Chibombo District Tribe 1 HRH Chief Chitanda Lenje People 2 HRH Chieftainess Mungule Lenje People 3 HRH Chief Liteta Lenje People B. Chisamba District 1 HRH Chief Chamuka Lenje People C. Kapiri Mposhi District 1 HRH Senior Chief Chipepo Lenje People 2 HRH Chief Mukonchi Swaka People 3 HRH Chief Nkole Swaka People D. Ngabwe District 1 HRH Chief Ngabwe Lima/Lenje People 2 HRH Chief Mukubwe Lima/Lenje People E. Mkushi District 1 HRHChief Chitina Swaka People 2 HRH Chief Shaibila Lala People 3 HRH Chief Mulungwe Lala People F. Luano District 1 HRH Senior Chief Mboroma Lala People 2 HRH Chief Chembe Lala People 3 HRH Chief Chikupili Swaka People 4 HRH Chief Kanyesha Lala People 5 HRHChief Kaundula Lala People 6 HRH Chief Mboshya Lala People G. Mumbwa District 1 HRH Chief Chibuluma Kaonde/Ila People 2 HRH Chieftainess Kabulwebulwe Nkoya People 3 HRH Chief Kaindu Kaonde People 4 HRH Chief Moono Ila People 5 HRH Chief Mulendema Ila People 6 HRH Chief Mumba Kaonde People H. Serenje District 1 HRH Senior Chief Muchinda Lala People 2 HRH Chief Kabamba Lala People 3 HRh Chief Chisomo Lala People 4 HRH Chief Mailo Lala People 5 HRH Chieftainess Serenje Lala People 6 HRH Chief Chibale Lala People I. Chitambo District 1 HRH Chief Chitambo Lala People 2 HRH Chief Muchinka Lala People J. Itezhi Tezhi District 1 HRH Chieftainess Muwezwa Ila People 2 HRH Chief Chilyabufu Ila People 3 HRH Chief Musungwa Ila People 4 HRH Chief Shezongo Ila People 5 HRH Chief Shimbizhi Ila People 6 HRH Chief Kaingu Ila People K. -

Storytelling in Northern Zambia: Theory, Method, Practice and Other Necessary Fictions

To access digital resources including: blog posts videos online appendices and to purchase copies of this book in: hardback paperback ebook editions Go to: https://www.openbookpublishers.com/product/137 Open Book Publishers is a non-profit independent initiative. We rely on sales and donations to continue publishing high-quality academic works. Man playing the banjo, Kaputa (northern Zambia), 1976. Photo by Robert Cancel World Oral Literature Series: Volume 3 Storytelling in Northern Zambia: Theory, Method, Practice and Other Necessary Fictions Robert Cancel http://www.openbookpublishers.com © 2013 Robert Cancel. Foreword © 2013 Mark Turin. This book is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported license (CC-BY 3.0). This license allows you to share, copy, distribute and transmit the work; to adapt the work and to make commercial use of the work providing attribution is made the respective authors (but not in any way that suggests that they endorse you or your use of the work). Further details available at http:// creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/ Attribution should include the following information: Cancel, Robert. Storytelling in Northern Zambia: Theory, Method, Practice and Other Necessary Fictions. Cambridge, UK: Open Book Publishers, 2013. This is the third volume in the World Oral Literature Series, published in association with the World Oral Literature Project. World Oral Literature Series: ISSN: 2050-7933 Digital material and resources associated with this volume are hosted by the World Oral Literature Project (http://www.oralliterature.org/collections/rcancel001.html) and Open Book Publishers (http://www.openbookpublishers.com/isbn/9781909254596). ISBN Hardback: 978-1-909254-60-2 ISBN Paperback: 978-1-909254-59-6 ISBN Digital (PDF): 978-1-909254-61-9 ISBN Digital ebook (epub): 978-1-909254-62-6 ISBN Digital ebook (mobi): 978-1-909254-63-3 DOI: 10.11647/OBP.0033 Cover image: Mr. -

Cholera Outbreak in Chienge and Nchelenge Fishing Camps, Zambia, 2017

OUTBREAK REPORT Cholera Outbreak in Chienge and Nchelenge Fishing Camps, Zambia, 2017 A Gama1, 2, 3, P Kabwe 1,2, F Nanzaluka 1,2, N Langa1,2, LS Mutale 1,2, L Mwanamoonga2,4,5, G Moonga5, G Chongwe5, N Sinyange1, 2,3 1. Field Epidemiology Training Programme, Lusaka, Zambia 2. Ministry of Health, Government of the Republic of Zambia, Lusaka, Zambia 3. Zambia National Public Health Institute, Lusaka, Zambia 4. University Teaching Hospital, Lusaka, Zambia 5. University of Zambia, Lusaka, Zambia Correspondence: Angela Gama ([email protected]) Citation style for this article: Gama A, Kabwe P, Nanzaluka F et al. Cholera Outbreak in Chienge and Nchelenge Fishing Camps, Zambia, 2017. Health Press Zambia Bull. 2017;2(1), pp12-19. On the 15th of February, 2017, the first case of suspected cholera was Zambia have been reported in Lusaka province followed by reported from Chienge district which has fishing camps with its neighbor district Nchelenge. We investigated the extent, the serotype of the Vibrio Luapula province (7%) [3]. cholera and possible sources of exposure of the outbreak. A suspected cholera case was defined as any resident from Chienge or Nchelenge who presented with acute watery diarrhea from February 14th Nchelenge had recorded a total of 1, 155 cumulative cases through April 4th 2017. A Confirmed cholera case was defined as a suspected cholera case in which Vibrio cholerae O1 or O139 was isolated through of cholera from 2002 to 2007 [5]. Chienge district reported culture. Rectal swabs from three case-patients were collected for culture. We interviewed suspected case-patients using a semi structured questionnaire. -

Preparatory Survey Report on the Project for Groundwater Development in Luapula Province Phase 3 in the Republic of Zambia

The Republic of Zambia Ministry of Local Government and Housing PREPARATORY SURVEY REPORT ON THE PROJECT FOR GROUNDWATER DEVELOPMENT IN LUAPULA PROVINCE PHASE 3 IN THE REPUBLIC OF ZAMBIA April 2014 JAPAN INTERNATIONAL COOPERATION AGENCY JAPAN TECHNO CO., LTD. EARTH SYSTEM SCIENCE CO., LTD. GE JR 14-103 The Republic of Zambia Ministry of Local Government and Housing PREPARATORY SURVEY REPORT ON THE PROJECT FOR GROUNDWATER DEVELOPMENT IN LUAPULA PROVINCE PHASE 3 IN THE REPUBLIC OF ZAMBIA April 2014 JAPAN INTERNATIONAL COOPERATION AGENCY JAPAN TECHNO CO., LTD. EARTH SYSTEM SCIENCE CO., LTD. SUMMARY Summary 1. General Description The Republic of Zambia (hereinafter referred to as “Zambia”), located in the southern part of the African continent, is a landlocked country bordering Tanzania, Malawi, Mozambique, Zimbabwe, Botswana, Namibia, Angola and the Democratic Republic of Congo. Its land area is about 752,610km2, which is approximately twice larger than that of Japan. Zambia is located in the tropical zone between latitudes 8ºS and 18º S, and its altitudes are from 900m to 1,500m. Because of its geographical location, the country has a relatively mild tropical savanna climate and has distinctive rainy and dry seasons, with the former one from November to March and the other from April to October. It has an annual precipitation of 700mm to more than 1,500mm, which increases from south to north. Zambia consists of nine provinces (Luapula, Northern, Eastern, Central, Copperbelt, Northwestern, Western, Lusaka and Southern) where the Project targets four districts (Nchelenge, Mwense, Mansa and Milenge) in Luapula Province. While the average yearly temperature of Zambia ranges from 15 ºC to 35 ºC, in the Project target area of Luapula Province, it ranges from 20 ºC to 25 ºC. -

Newaug Newsletter.Pub

The Morrows in Zambia Special points of interest: Aug-Sep, 2005 • Thomas takes an 8 day trip into the African Bush. An unforgettable bush trip! The 24th of July was the day different walks of life. We col- sengers with baggage. While Thousands of peo- when our 8 day journey to the lected all of the necessary equip- that was being worked out, we Luapula province would begin. ment, baggage, and food for our went to the local church to set ple watch the Jesus To undertake such a trip here in trip, packed them and had a up the Jesus Film. Once the Film and come to Zambia takes a lot of planning good prayer. darkness fell upon us, and the Christ. and prayer; as in any developing We left the house by 5:30 am. projector lights went on, swarms countries, unpredictable circum- Our first camp would be ap- of lake gnats invaded us. When I Tom sleeps under stances can and often do happen. proximately six hours away at swallowed some of the bugs the the stars, braves the This year I wanted to accom- the small town of Samfya, a pastors said that was a sign that lakeshore fishing spot. we were being blessed. HA! waves of large lakes, After a few hours of travel While the two hour film was and eats all manner I noticed we started to re- showing, we went to a tradi- of strange foods. duce speed. The driver tional Bangweulu restaurant by pulled over and said his the lake for a plate of 3 lumps of The Mutomboko pedal was to the floor but nshima, chopped rape, and 2 just couldn’t get any speed! medium sized bream fish--all for Ceremony is revis- We looked over the engine 7,000 Kwacha ($1.50).